Читать книгу A Shape in the Dark - Bjorn Dihle - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеOn October 1, 2018, my two brothers and I packed the meat, bones, and hide of a mountain goat down a mountain in northern Southeast Alaska. Near the ocean, we walked through an estuary that had been rototilled by hungry bears digging roots. The salmon runs and berries had failed that year. We paused to get water from a stream as the sunset illuminated mountains and ocean in soft layers of red. A fresh set of brown bear tracks crossed in the sand. Its humanlike hind track was a little over a foot long, and its pigeon-toed front track was over eight inches wide. I guessed it would stand more than eight feet on its hind legs and weigh close to eight hundred pounds—a large male in this region. Using our headlamps, we traveled through darkness, following the same game trail the bear was traveling through the forest. I thought how by now, up on the mountain, all that remained of the goat was a stain of blood and offal, and a few bones that had already been picked clean by eagles and ravens. Soon, a wolf, bear, or wolverine would crunch them to feast on marrow, and then the broken remains would be reabsorbed by the mountain. My light illuminated gnarled trees rising into the black, and I yelled out a warning to the bear. I knew it could hear me, and sensing its restlessness, I thanked it for allowing my brothers and me to pass through the woods.

Late that night, after I made it home, I learned that a young man had been killed by a brown bear on nearby Admiralty Island that morning. The man had been an eighteen-year-old Oklahoman who had just arrived in Alaska and begun a job as a driller’s assistant. He and another worker had been helicoptered to a remote drilling site, leased by the Hecla Greens Creek Mining Company, high in the mountains on the island. The press release and newspaper articles that followed had few details as to what happened. I would hear later from people with ties to the mine that the young man had walked away from the drill pad to check a hose or look for water. Neither of the men had been armed. When the Oklahoman didn’t return, the other contractor went looking and found a female bear with two big cubs eating him. The man radioed for help, summoning a helicopter, which tried to buzz the bears off the body. The bears wouldn’t leave and were shot several times with a .375 rifle from the air, killing them.

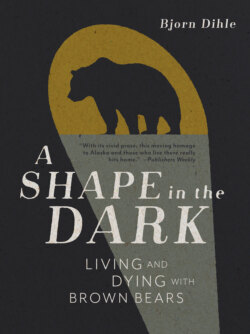

This book is about our relationship with brown bears, which, in case there’s any confusion, is the same species as the grizzly bear. During the last twenty years, I’ve spent a significant amount of time exploring wild places across Alaska and, for most of the last decade, worked as a guide taking people and film crews throughout Southeast Alaska to watch and film brown bears. Before and even after beginning this project, there have been times I almost hated bears. Like most feelings of hostility, mine were rooted in fear. Yet, there is no place I love more than grizzly country, and no animal has intrigued and challenged me more than the bear.

I grew up in Juneau and live on nearby Douglas Island, both of which are just a few miles’ boat ride from Admiralty Island. The roughly hundred-mile-by-seventeen-mile island lies in the northern section of the Alexander Archipelago, a group of over a thousand rainforest islands in Southeast Alaska. The archipelago and the adjacent rugged mainland comprise the Tongass National Forest. Established by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1907, the Tongass is wet, wild, and America’s largest national forest at nearly 26,500 square miles. Admiralty is part of the ABC Islands (Admiralty, Baranof, Chichagof, and—though most folks have never heard of them—Yakobi and Kruzof Islands), which make up the northern part of the Alexander Archipelago. These five islands are ecologically similar — historically, they have big runs of salmon and a lot of brown bears and Sitka black-tailed deer. The true name of Admiralty is Kootznoowoo, which in Lingít, the language of the Tlingit people who’ve lived in Southeast Alaska since time immemorial, translates to something like “fortress of the bears.” Admiralty is known for its exceptionally dark, even black, brown bears. These black grizzlies were once commonly called Shiras bears—and used as a rallying cry for conservationists who fought to keep the island from being clear-cut. For the most part, the only people who still use the term Shiras are old-timers who remember the battle for Admiralty. The island’s bear population is roughly estimated to be one per square mile, meaning that it likely has more brown bears than the entire Lower 48.

It had been nearly a century since someone had been killed on Admiralty by a bear. Both deaths could have been avoided and were the result of people having little understanding of bears. Nearly every documented brown bear fatality in Southeast Alaska has occurred late in the year when bears enter a state of hyperphagia. (The one exception is a garbage bear that ate a man in Hyder, a tiny community near Alaska’s southern border with Canada, in July of 2000.) Each fall, when the salmon runs peter out, an internal switch goes off in bears that makes them more voracious and, often, agitated. On Admiralty and neighboring islands, they spend more time in the high country feeding on berries and anything else with caloric value. A bear has to gain around 30 percent of what it weighed in the spring or it won’t survive the long winter sleep.

Far fewer people die at the teeth and claws of brown bears in Alaska than most people realize. There were no documented fatalities in the state from 2006 until the fall of 2012, when two men died in separate attacks. There were no fatalities from 2013 until the summer of 2018, when a man was killed in Eagle River, near Anchorage. In contrast, nearly 2,000 of Alaska’s estimated population of 30,000 to 40,000 brown bears are killed by sport hunters annually. In the Kodiak Archipelago alone, 600 miles west of Admiralty Island, $5 million is spent on bear hunts each year, and around 180 bears are killed. There’s been only one documented case of a bear killing someone there in the last 75 years, so the demon monster mythology often applied to bears and perpetuated by media is far from the truth. Brown bears are generally not aggressive toward people unless threatened or surprised at close quarters, and those encounters are usually relatively easy to avoid. Still, there’s no way to make bears safe, although people have tried and failed.

I PUT MY SHARE OF GOAT MEAT AND BONES IN THE REFRIGERATOR, TOOK a beer into the shower, and then lay in bed unable to sleep. My body was exhausted, but my mind wouldn’t turn off. The residue of the goat’s blood smelled subtle and sweet. My partner, MC, pregnant with our first child, snored gently next to me. Our golden retriever, Fen, shifted and laid her head on my foot. Still unable to sleep, I moved to the living room and stared out at the black of a mountain rising from the ocean in the darkness. The lights of Juneau shone weakly to the north across Gastineau Channel. I imagined the big bear whose tracks my brothers and I had followed earlier resting at the base of an ancient tree or prowling the night in search of something to ease its hunger. I thought of the fetus that was my kid, floating in amniotic fluid and protected from the world by a few thin layers of MC’s flesh. I thought of the Oklahoman’s parents and felt a tightening in my guts.

Pouring whiskey into a mason jar, I remembered how the fall before, while deer hunting on Admiralty Island, I had come upon a den on a steep slope beneath a giant spruce tree. A bear had recently excavated piles of dirt. Chances were, the animal lay feet away, asleep atop a bed of moss in the darkness. The hair on the back of my neck stood up. I quietly chambered a round in my rifle and held it to my shoulder. Taking a step back, I glanced about the shadowy rainforest. I imagined the bear rushing forth from the earth and charging down the mountain away from me. Then I imagined it rushing forth from the earth, knocking me down, and eating me. Nothing but my breathing and heartbeat disturbed the quiet. Then I crept closer and peered inside the den, like a moth drawn toward a flame.

I studied the darkness inside my condo and then looked out at the darkness outside the window. After a while, much like our ancestors who built fires to keep away the monsters, I opened my laptop and stared at the lit-up screen, hoping the words would come.