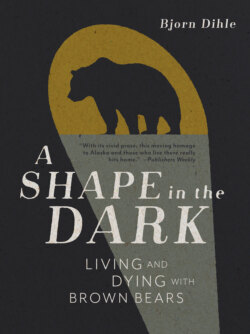

Читать книгу A Shape in the Dark - Bjorn Dihle - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 2 Blood Trails

ОглавлениеThey numbered no more than a thousand, maybe two and their heyday lasted less than 20 years, but the mountain men left an indelible mark on American and world history. . . . In 1856 Antoine Robidoux could account for only three out of 300 from thirty years earlier. In Arizona during the 1820s, James Ohio Pattie recalled sixteen survived out of 160 in one year on the Gila River. Fatal quarrels with friends, thirst, starvation, storm, accidents and disease took their toll but Indians and grizzlies seems to have accounted for most to “go under” as they preferred to call death. Grizzlies ran in packs of fifty and sixty back then and had no fear of man. Trappers reported seeing as many as 220 in a day. Weighing 1,000 lbs. and able to run to speeds up to thirty-five mph. Even when taking in their proclivity to exaggerate, the numbers must have been high.

—Marshall Trimble, “Mountain Men”

In 1814, five years after Meriwether Lewis was buried at Grinder’s Stand, the Corps of Discovery’s journals were published. In it, people read an account of a western America filled with seemingly limitless game, adventure, and economic opportunity. Indigenous peoples were described as being mostly harmless, with the implication that the only thing contending with white men for the dominion of the continent was the grizzly bear. Readers were familiar with the black bear but viewed the animal mostly as a resource and an occasional nuisance. The grizzly, on the other hand, radiated danger and presented an existential threat to the expansion of the young nation.

For Jedediah Smith, the book of Lewis and Clark’s journals was akin to the Bible. Legend has it that after a friend and mentor gifted him a copy at age fifteen, he carried it with him for the rest of his life. Smith was in his early twenties when he traveled west to St. Louis in 1822 looking for employment and adventure. The world was mad for beaver fur hats, and the market’s supply depended on American Indian trappers. Alcohol, and a lot of it, was involved in bartering. In 1822 it became law that booze could no longer be used in trade with Natives, which in part led to the formation of free trappers—parties of largely white trappers that companies would outfit to attain beaver pelts. Smith, dreaming of his chance to follow in the footsteps of Lewis and Clark, signed on with one such group, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, founded by William Henry Ashley and Andrew Henry. He was joined by a ragtag assemblage of St. Louis drunks and dreamers who agreed to ascend the Missouri River and spend between one and three years engaged in the fur trade. In the ranks were Hugh Glass, Jim Bridger, and others who would become legendary mountain men. They became known as Ashley’s Hundred.

It’s uncertain why the grizzly, despite occupying what is now the Lower 48 for at least 13,000 years, never made it east of the Mississippi River. Most of Ashley’s men had no experience with the animal—they no doubt spoke obsessively about the bear, retelling stories from the journals of Lewis and Clark, as they slowly lined their way up the Missouri River. Some of the more seasoned men had their own tales, many of which were almost too wild to believe. There was more danger than just bears stirring in the wild country they were headed into though. Relations with Indigenous peoples were becoming tenser as epidemics of disease, alcohol, and increased contact disrupted their cultures.

After a winter spent building forts and trapping beaver, most of Ashley’s men were camped on a sandbar above the Missouri River near a heavily fortified village belonging to the Arikara people. The trappers were hoping to trade for horses to continue west in search of better beaver country. On the morning of June 2, between six hundred and eight hundred warriors opened fire on them in a surprise attack. Hugh Glass was shot in the leg before he, along with most of the men, took cover behind the gunned-down bodies of twitching, bleeding horses. Ashley had anchored his boat out in the river, and men in skiffs tried to rescue their companions. According to legend, Jedidiah Smith, while providing rifle fire, was the last man to abandon his position on the beach. Between twelve and fifteen of Ashley’s men died in what became known as the first Plains Indian War.

In August of 1823, Smith, Glass, and fifty other trappers returned to the Arikara village with the 6th Infantry and seven hundred Sioux warriors—the Sioux and Arikara had long been enemies. The Sioux charged ahead and were met by a comparable force of Arikara in the fields outside the village. One witness likened the fighting to a bunch of enraged bees. The Arikara warriors were retreating into the protection of their village’s fort as the mountain men and army arrived. The Sioux began mutilating and dismembering bodies, taunting their enemies to come out and fight. Fear suddenly rippled through the warriors as a Sioux shaman appeared amidst the carnage, crawling on all fours. The man growled and snorted, mimicking the movements of a grizzly. The Sioux begged their white comrades to look away as the shaman sniffed an Arikara corpse. With his teeth, he began ripping the flesh from the chest of the man. One can imagine young Jedediah Smith, along with the other mountain men, staring in terror and wonder.

THE SMELL OF THE SMOKE FROM THE RAZED ARIKARA VILLAGE WAS STILL on Hugh Glass as he followed Andrew Henry on a five-hundred-mile overland journey to Fort Henry, where the Yellowstone River joined the Missouri River. Partway there, Glass disobeyed orders, broke formation, and was traveling alone just beyond the other men. A grizzly rose from the brush, let out a low woof, and eyed the lone man. Nearby, her scared, anxious cub bawled. Perhaps Glass fired first, or perhaps the mere sight of a man was enough to make the bear charge. The other trappers heard Glass scream and hurried through the woods. After a volley of shots, the bear collapsed dead atop the mountain man. Henry and his men rolled the bear off to find Glass a torn and gruesome mess. Death would be merciful and quick, they assumed. The trappers made camp while he wheezed terribly through his torn throat.

Despite his being the subject of numerous books and a blockbuster movie, not a lot is known about Glass before he joined Ashley’s Hundred. A trapper who claimed to have been acquainted with him wrote that Glass was once a sailor and had been captured by pirates and forced into servitude. The story goes that Glass and another captive escaped a few years later, and the two wandered across Texas and Oklahoma before being captured by the Pawnee. The trapper related that though the companion was burned at the stake, Glass spent several years living with the Pawnee until he showed up in St. Louis around 1822.

Night fell, and Glass would not die. The Arikara were in the area and eager for revenge. Henry knew the longer they stayed put, the greater the risk of losing more men, or even the entire party. He offered a substantial amount of money to two men to keep a death vigil and bury Glass when the time came. John Fitzgerald and a nineteen-year-old, who some have theorized could have been Jim Bridger, volunteered. Henry and the rest of the men continued west, only to be attacked the following night. In the early dawn they left two of their men buried in shallow graves marked by crude crosses. It’s not known how long Fitzgerald and the youth waited with Glass. It probably wasn’t long, considering the likelihood of an Arikara attack. The two covered Glass with the skin of the grizzly as he lay wheezing, then took his rifle and possessions before heading toward Fort Henry.

Maybe it was the woodsy musk of fur or the smell of the rotting bear’s blood mixed with his own that roused Glass. He probably wondered if he was dead as he stared up at the sky. Much of what happened next is uncertain, but it’s likely Glass crawled over to the bloody, bloated bear carcass and rested his arm and face on her ribs. He studied the surrounding woods before biting and tearing away chunks of meat. He ate as much as he could, then began crawling toward Fort Kiowa. Historians estimate between two and three hundred miles separated him from the fort.

Meanwhile Jedediah Smith, who’d recently been promoted to captain, was leading a party west in search of better beaver country. He was going into terra incognita, places that even his heroes Lewis and Clark had never explored. The trip had not been easy; they had nearly died of thirst while traveling across what would soon be known as the Black Hills of South Dakota. Not long after, the mountain men were leading their horses through the brush above a creek bottom. A large grizzly appeared, then supposedly charged the line of panicking horses. Smith, with his rifle cocked, stepped out to meet the bear. A moment later the bear flattened him and engulfed his skull in its jaws, ripping his scalp and part of his face. Next, the bear bit into Smith’s side, picked the mountain man up, and shook him. Smith broke several ribs, but a musket ball pouch and hunting knife absorbed the brunt of the bite. The bear was killed before it could do more damage.

The mangled captain’s companions looked at him and were at a loss as to what to do. His scalp and ear were hanging from his skull, and the side of his face was badly torn. They discussed their options before addressing their wounded leader. Smith calmly asked if anyone had a needle and thread. The items were procured, but the men were reluctant to do what needed to be done next. Smith took charge and politely asked one man to do him the honor of sewing his ear and scalp back on his head. For the rest of his life, Smith would wear his hair long and combed over to hide his scars.

While Smith convalesced, Hugh Glass was crawling toward Fort Kiowa. He’d let maggots eat his rotting flesh to ward off infection and subsisted on rattlesnakes and carrion. Glass found Fort Kiowa empty but soon encountered and joined a boat manned by five French traders ascending the Missouri River. He wanted a reckoning with the men who’d deserted him badly enough that he was willing to return to Arikara territory. In an event of brutal irony, over the course of the upriver journey, Glass just missed John Fitzgerald, who floated down the Missouri with two other men in the cover of night. At one point, Glass—even though he had open wounds and likely broken bones yet to fuse back together—was put onshore to hunt meat. He was quickly attacked by a band of Arikara. Legend has it that a Mandan horseman plucked him up and whisked him to the safety of J. P. Tilton’s fur trading post, just down the Missouri River from the site of Lewis and Clark’s Fort Mandan. The French traders were slaughtered by Arikara not long after.

Traveling alone, Glass finally caught up with Andrew Henry and his fellow trappers at the end of December. He limped into Fort Henry looking more dead than alive and promptly forgave the young man who’d abandoned him, supposedly on account of his youth. Toward the end of winter, Glass headed south in search of Fitzgerald, traveling with four other trappers tasked with delivering a message to Ashley. On the Platte River, the party was attacked by a large group of Arikara. Glass hid in the brush, watching while two of his companions were hacked up. He snuck away in the dark of night and began another several-hundred-mile journey alone across the wilderness. This time he at least had a knife. Sometime in June, Glass made it to Fort Atkinson, in present-day Wisconsin, where he found Fitzgerald. It’s unclear what happened during the encounter, but Glass didn’t kill the man. Instead, he took back his rifle and headed down the Missouri to St. Louis.

Some would think that after what Smith and Glass had suffered, they would seek out an easier, safer livelihood. Something had gotten into their blood though. Maybe it was the mist on a creek at morning’s first light and the sweet smell of beaver. Maybe it was the wild open of the country and the herds of thousands of buffalo. Maybe it was the grizzly. Maybe they’d seen too much to ever be able to return to civilization.

Smith made it to 1831. He likely roamed farther than any other mountain man. Many scholars credit the routes he mapped with setting the foundation for western expansion. Comanches attacked him while he was traveling alone in Kansas. I wonder what his assailants thought when they lifted his scalp and saw his scars. I imagine the warriors plundering Smith’s outfit and finding the book of Lewis and Clark’s journals. I imagine them tearing out pages and scanning words like animal tracks. I imagine those torn pages rustling in the wind around Smith’s mutilated corpse long after the Comanches rode on.

Glass made it until 1833, when, after spending years trapping beaver in the Southwest, he returned to the upper Missouri. Early that winter, near Fort Cass—not far from where the city of Billings, Montana, now stands— he and two other trappers were ambushed by Arikara while checking their beaver sets. The war party left pieces of their scalps impaled on sharpened sticks above their naked and mutilated bodies.

I GREW UP LOVING TO HEAR ABOUT THE MOUNTAIN MEN AND WISHING I could have lived during their era. My dad would sing the Davy Crockett: King of the Wild Frontier Disney theme song to me most nights before bed. The most evocative line was the one about him killing a bear when he was only three. I, too, wanted to match myself against bears and mountains. Even as a young adult, I imagined that the lives of men like Hugh Glass and Jedediah Smith possessed a sort of meaning and freedom that evaded my own.

In the fall of 2003, fed up with civilization, I dropped out of college and decided to roam the mountains. I was two hundred years late, but Alaska still had wild country, where you could wander for days without seeing a road or another person. Once, while camped in the eastern Alaska Range, I woke unable to move. Something—my first thought was a bear—loomed above my tent. I imagined it collapsing and tearing the tent and dragging me into the night. Instead, a voice spoke in a language I’d never heard. Other voices chattered in. It was obvious they were discussing me. One voice, calmer than the rest, seemed to exert control over the others, and soon their discussion faded to silence. In the gray dawn, I emerged from my tent and studied a wall of rugged mountains. It was a dream, I told myself. For the first time in my life, I worried I was losing my mind.

Ten days later an old trapper who ran a trap line off the Yukon River picked me up while I was hitchhiking to Fairbanks. We talked about hunting, bears, and wolves.

“I remember one wolf,” he said. “She was pure white, almost as if she glowed. She reminded me of those arctic wolves you see in National Geographic magazines—the ones that live on those islands off the Arctic coast. She hung around my line for a couple months. I tried every trick I know, but I couldn’t catch her in a trap, and she never let me close enough to get a shot at her. One day I saw her out around five hundred yards across the river. Shot her. Found a good blood trail but never found her. That was the most beautiful I’ve seen.”

In the ensuing silence, I studied the trapper out of the corner of my eye. I mentioned a golden-red grizzly I’d had a standoff with high in the mountains a few days prior. The bear had refused to move when I clambered over a knife-edge ridge and came upon it—I’d wondered if it had been eating a Dall sheep. A grizzly protecting a kill, similar to a mom with cubs, is more likely to be aggressive, even attack. The bear and I had stared at each other for a while before I slowly backed away.

“A couple from California got ate last week out on the Alaska Peninsula. It’s all over the news. This is the most dangerous time of the year. You be careful out there,” the trapper said.

He dropped me off at a Kentucky Fried Chicken in the industrial outskirts of Fairbanks. A short while later, I sat with my greasy Styrofoam thinking about being eaten and wondering how strong a hold I had on my sanity. I glanced around at other people, then outside at snow-covered buildings rising into the gray, wishing I was back in the mountains.

A FEW DAYS LATER, I HITCHHIKED OUT OF THE CITY HEADING FOR THE Hayes Range for a monthlong wander. A young woman with a cooing baby gave me a two-hour ride to Delta Junction. Then, after I spent a couple of hours pacing back and forth in the snow on the shoulder of the Richardson Highway, trying to stay warm, a man with a big red beard picked me up. I put my pack next to a tote filled with spruce boughs, traps, and moose bones, hide, and scraps in the back of his truck.

“Going to make some sets for coyotes. Not enough wolves around anymore to keep their numbers in check,” the man said.

He told me the Hayes Range was crawling with grizzlies and they were mean but all should be in their dens, except for maybe a winter bear—an animal that doesn’t den or emerges early because it doesn’t have enough reserves. These bears are desperate and the most dangerous.

After he dropped me off, I shouldered my heavy pack and trudged off into the snowy forest, dragging a sled with additional gear behind me.

A week later I watched a family of beavers frantically adding willow branches to their food cache. The world was shrouded in turbulent gray clouds; a blizzard looked like it would soon set in. A herd of caribou plodded through deep snow along a distant rise. It was mid-November, temperatures were falling rapidly, and days were growing shorter. I had not seen so much as a bear track during the last several days. In fact, in the five weeks since I’d dropped out of school and been in the field, I’d seen only two grizzlies. Still, most nights I’d lie awake thinking about bears, listening to the different sounds, and often wonder if one was approaching in the darkness.

Near dusk, a beaver and its kit crawled up onto the shore. I was hoping to spend another three weeks out and had been rationing my food; I was hungry in a way most people wouldn’t understand. I checked my .22 rifle and moved quickly toward them. I crawled through snow until I was just feet away. I aimed at the kit’s head and then shifted to its parent. At the crack of my .22, the beaver’s head fell to the side, and it collapsed atop the sloping frozen mud. I ran and tried to grab hold as the beaver flopped into the lake, splashing into the black water, but when I reached in, I came up with nothing. Heavy snow fell as I paced the shore until last light, feeling nauseated with guilt, hoping the beaver would float to the surface. Its mate swam back and forth searching long into the night. When I woke early the next morning, the lake had iced over and the mountains glowed silver in the moonlight beneath a blanket of fresh snow.

I was inexperienced with deep cold, and a few weeks later I developed frostbite. It spread like a burn across my fingers, nose, cheeks, and toes. My feet were the worst—I could not feel them other than as a slight, numbed pain. I snowshoed for fifty continuous hours, through darkness streaked with aurora, across the tundra, and then west along the Denali Highway. The dirt road is closed to traffic during the winter, but it offered easier travel on snowshoes. A group of forty or so caribou spooked and came charging out of the brush across the road. The snow was so deep that the animals breaking trail weren’t going more than five miles per hour. The caribou in the back of the progression were going faster and half-trampling the animals in front of them. At the rear of the herd were two gray wolves that looked almost as large as the caribou. The two wolves jogged along, the one in the lead seemingly touching the hindquarters of the caribou last in line. The wolf turned, looked back at its companion, and grinned. A few moments later, the caribou and wolves disappeared into the brush. Across the road, they’d left a deep trench of a trail flecked with droplets of blood glowing red against the white of the snow.

When I made it back to Fairbanks, I had to go to the hospital. The doctor who did my triage told me I was probably going to lose half my right foot to gangrene—in the end I lost only a minimal amount of flesh and toenails. I thought about the mountain men during my convalescence. Some claim they were heroes who ventured into the unknown and blazed a path for civilization across the continent. Others say they were murderers, even the perpetrators of genocide. I told myself I was no longer envious of their brutal and lonesome lives.

Not long after, I encountered the only grizzly I’ve ever seen in the Lower 48. It was in October, in the Lewis and Clark National Forest in Montana, a few hundred miles from where Hugh Glass was killed. The night before, at a tiny road-stop bar, an affable American Indian bartender had warned me about how many bears were in the area. In the morning, I was walking along a trail through the woods when, from around a corner, a silver-tipped grizzly came walking my way.

The mountain men are long gone. The American grizzly, besides tiny remnant populations in pockets of Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming, has vanished too, but as the bear and I stared at each other, I felt a timeless electricity course through me. The grizzly, instead of attacking or displaying even a minor sign of aggression, swung around and lumbered away.