Читать книгу Energy Warriors - Bob Ellal - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

SOUL BROTHER BEOWULF

Unless he is already doomed, fortune is apt to favor the man who keeps his nerve. The maxim from the ancient Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf reverberated in my skull, like a mantra, until the words no longer made sense and were simply a collection of sounds. My breathing slowed and deepened; my mind felt calm. I felt far away from the isolation room in the bone marrow transplant ward, though high-dose chemotherapy drugs dripped through IV tubes into a catheter implanted in my chest.

Minutes ago I’d been anything but serene; anxiety had welled up inside my chest like a giant palm pressing on my diaphragm.

I watched the nurse open the plastic levers on the IV lines and prepare to exit the room. She stood briefly to give me words of encouragement when she noticed the small stack of books on the wheeled tray near my bed.

“Beowulf?” She picked up a translation of Beowulf with a photo on the cover of an ancient Anglo-Saxon war mask, iron mouth smiling, spaces for a warrior’s eyes hollow.

“God Almighty, you should be reading something lighter, like War and Peace.”

“I can’t help it—Beowulf is my soul brother. You see, we’re both born monster killers.”

“Oh, I see.” She shook her head. I forged a smile on my face, hoping it looked grim and determined like the mouth on the iron war mask. As she closed the steel door to the tiny isolation room, signaling the beginning of the month-long transplant process, I scanned my surroundings.

Fifteen years ago the room was state-of-the-art, built specifically for the transplant procedure. At that time, the medical experts thought that any hint of a germ would be fatal for the patient after his blood counts dropped to ground zero, so they designed the room to resemble something out of the space program, a combination of the sterility of a NASA “clean room” with the roominess of an Apollo space capsule.

The walls and ceiling were composed of aluminum sheets joined by riveted metal strips, all painted hospital white; the room itself was about 12' by 12' and perhaps 6-1/2' high. The bed dominated the workspace, leaving room for only a single chair, medical monitors and equipment, and the portable commode with its high back and arms for comfort (useful when diarrhea struck every 15 minutes).

A single window provided a view of the outside world, in this case the hospital parking lots. Its double-paned glass slightly warped the vista and was dense enough to be bulletproof. Terrific—no assassin’s bullet would find me! I was really worried about that possibility….

Those were the old days; today the human contact is slightly less antiseptic—the nurses and doctors condom themselves with disposable gowns, gloves, and filter masks, bypassing the screen entirely.

Panic. Shallow, quick breathing and thoughts of death pinball through the mind. It’s that door—once the door clicks shut and the air no longer flows naturally into the room, the panic sets in. The noise of the compressor blowing filtered air into the cramped room increases the sense of claustrophobia and constriction in the chest. Is this how the gas chamber feels?

Quick: rip the tubes from your veins and escape into the corridor. They can’t hold you here! From outside you hear the sounds of the workmen’s tools as they modernize other rooms on this floor to accommodate future transplant patients.

Steal a hardhat and a pair of coveralls and escape into the working world. It’s Friday, and you imagine returning home after a long week of work… your sons meet you in the driveway, riding circles around the car on their bikes as you pull up to park.

Then the scene switches. Several boys ride bicycles, including your two sons. They seem oblivious to my presence. They are talking to each other.

“What happened to your father?”

“He died.” The older boy answers, while the younger rides his bike in ever tightening circles.

“Was it in a war or an accident or something?”

“No, he got sick and died in a hospital.”

Your wife comes to the screen door; face puffy, eyes empty, like the hollow sockets in the Anglo-Saxon war mask.

This is agony! I don’t want to die in this place!

Keep your nerve, man... yeah, easy if you’re Beowulf, the hero of my long-gone Anglo-Saxon ancestors, a superman who could tear the arms off monsters with his bare hands. But what if you’re me, Corporate Bob, a word-weaver, a man who might be clever with people but can barely tear the arms off a Barbie doll? How do you keep your nerve if you have lymphoma cancer? Huge biceps and a washboard waist won’t help you here.

Damn. I’m in for a screwing this time. This is my second transplant, so I have the dubious advantage of knowing what to expect: Over the next few days, the chemotherapy will destroy my bone marrow and, with luck, all the cancer cells existing in my body. It also could destroy me by causing a heart attack, damaging my organs, allowing infections like pneumonia to arise, or killing me in numerous other ways.

The less lethal but uncomfortable side effects of the chemo could include rampant diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, fevers and chills, as well as complete fatigue and depression. In short, I am facing what amounts to three or four weeks of a simulated cheap red wine hangover—one that could prove fatal.

If I survive the chemotherapy, they’ll pour my stem cells (baby white cells harvested from my blood) back into me. These little buggers are smart: hang them off an IV pole from a bag that looks like watery tomato sauce and they swim their way back into the bone marrow to recreate my immune system. Of course, something could go horribly wrong, something mentioned in sterile print in the release form I signed before the doctors began the treatment. Sometimes the stem cells refuse to take or engraft properly, and you are left without an immune system. But not for long....

If the stem cells do engraft properly, you’re not home-free. No, those nasty mouth sores prevent boredom from setting in. Once a patient’s white blood cell count dips into the nether regions, the mouth sores appear: raw, leprous wounds covering the tongue, the inside of the mouth, the throat, and sometimes the esophagus. The pain is so intense that you cannot talk or swallow—never mind eat—without the help of a morphine derivative constantly dripping into you.

Control. I can’t lose my nerve... Okay, Beowulf, let’s step away from this scene and observe what is happening. My mind is a tangled jungle canopy. Thoughts careen through the foliage like frightened monkeys chattering and swinging from its vines. I am under heavy stress and in a state of fight or flight. If this continues, the adrenal glands atop my kidneys will continuously flood my bloodstream with adrenaline and other hormones.

Short term, this hormonal boost is positive: it gives humans the energy to handle extraordinary situations, like fighting a monster or escaping from its claws. But suppose the monster is within you, and you can’t fight or can’t run away? The hormones inundating you will overload your body’s systems and eventually burn you up.

Can’t have this! The combination of the cancer and the chemotherapy is enough to wear anyone down. Must seek a state of stillness so my immune system will allow the treatment to do its job without interference from my body. How? You know how….

Seize the monkey. The monkey in Chinese philosophy is the emotional mind that chatters unceasingly, cluttering the brain with questions, thoughts, fears and judgments that prevent a calm mental state. This monkey can be dangerous if you’re ill: if the mind is in a state of panic, the body responds and triggers its panic systems.

How to center the mind? With the breathing. The breath is the bridge that links the mind and body. Regulate the breathing with slow, deep inhalations from the bottom of your lungs, seizing the monkey, calming the emotional mind by removing the chaos of irrational thoughts. As the mind calms, so does the body, from a state of alarm to a state of neutrality.

Fortune is apt to favor the man who keeps his nerve: the formula for survival. That is what my Anglo-Saxon will tells me to do. But how do I maintain my nerve over months and years of continuous battles, when fatigue and world-weariness wears me down? What is the mechanism to keep the will strong and prevent it from faltering?

Breathing, again, breathing. When the will falters, when we’re at the breaking point, let go. Don’t quit, that’s different. Let go. Breathe. Let things happen, don’t try to make things happen. As a wise mystic once told me: stop thinking and permit. Permit. Easy to say. Hard to do.

Despite my fatigue I stand near the edge of the bed, the tubes in my chest connecting me like umbilical cords to the IV bottles hanging from the metal pole. Gently I bend my knees, sink my body and raise my arms in an arc in front of my chest, fingertips a few inches apart, my spine straight, the top of my head pressing lightly toward heaven.

My arms embrace the image of a tree, drawing its clean oxygen into me as it pulls dirty carbon dioxide, cancer cells and toxic chemotherapy from my body. The bottoms of my lungs fill with air, expanding my abdomen and the area in the small of my back between the kidneys.

Focus on breathing, the intermediary between mind and body. In and out, inhale and exhale, no pause, a continuous cycle. Gradually fear dissipates as my mind shifts to the action of my lungs. Beowulf ’s formula for survival echoes in my mind and quickly condenses itself to two words: “fortune” as I inhale, and “nerve” as I exhale. After twenty or thirty breaths the words lose meaning and merely became sounds. The pressure within my chest disappears.

Slowly a ghostly serpent of energy arises within me and spirals its way up my spine. It entwines itself in the intricate web of bone, nerve, muscle, and tissue that ultimately connects to every part of my body, preventing it from collapsing to the earth into an accordion of lifeless flesh.

This snake penetrates my brain and drifts upward through the top of my skull into the puzzle of bony plates that seam together in infancy. I exhale and the serpent gathers mass and structure and slithers downward over my forehead to slip through a vagina of skin that seems to open between my eyes. It descends down my throat, behind my sternum, and settles in a coil below my navel, liquefying into a molten, spinning ball of heat that sends tiny, stimulating currents of sunlight into my penis and testicles.

My lungs fill and this tiny sun reforms itself into a great, diaphanous cobra that again winds its way up my spinal column. Now it’s no longer a snake but a spiral staircase of swirling gases, a fragile molecule of DNA, its atoms held together by the opposing forces of electrical attraction and repulsion. Eventually its head catches up with its tail, engulfs it, and it changes into a continuous orbit of energy revolving within my torso and arced arms....

The snake disappears, the image of the tree dissipates, the hospital room dematerializes. I too depart, along with the threat of lymphoma cancer that has dogged me for five years. All that is left is a pulsing of energy that coordinates itself with the action of my lungs, of which I am barely aware. Corporate Bob is no longer an entity; he has melded into the earth and sky.

I’ve seized the monkey. Monsters half-heartedly stir from their corners, moving through me and harmlessly evaporating. Stillness descends like a great, pealing crack of silence. What a paradox! This sensation of peace is not one of absence of feeling; it’s as though a quiet energy pulses uniformly within me and around me, as though the very molecules of the air are positively charged, alive.

I am still, and this electric tranquility also vibrates in the walls, ceilings, medical equipment and portable commode that constitute this isolation room. It is now my room, my space, my place to heal. Monsters cannot survive here, only warriors—energy warriors.

QIGONG—MIND/BODY MEDICINE, OR ALL IN MY HEAD?

“Balance your weight equally on your feet. Keep your arms curved in an arc at chest level, fingers a few inches apart, pointing at one another. Relax your shoulders, tuck your tailbone and straighten your spine. Your head should press heaven, as though it’s suspended from above by a string, which lengthens your backbone and creates space between the vertebrae.

“Touch your tongue lightly against the roof of your mouth. Expand your belly and the small of your back as you breathe, and open and close the huiyin cavity between your genitals and anus at the same time. Okay, good… now relax.”

Ramel, my meditation teacher, recited the familiar list of instructions for The Standing Post meditation known as Embracing the Tree. I’d practiced it almost every day since I’d met him, and could maintain the position for one hour without lowering my arms.

That seemed like a major accomplishment—when we first began our private lessons six months earlier, pain from the tumor in my right shoulder prevented me from even lifting my right arm to chest level, never mind holding it there. Since then I’d undergone months of preliminary chemotherapy to eradicate the cancer and prepare for the bone marrow transplant designed to “cure” the disease forever. I’d practiced the art of Qigong—which means “energy study” in Chinese—every day to keep my mind and body strong.

Qigong (pronounced chee-gung) has been practiced and developed by the Chinese people for more than 5,000 years. The exercises and meditations are designed to integrate the mind and body to stimulate the unimpeded flow of qi (pronounced chee), or bio-electricity, through meridians and channels in the body. The Chinese feel that this vital energy permeates the universe and can be controlled in the human body through various means such as meditation, herbal medicines, diet, and acupuncture. When this qi flows properly, good health is maintained.

Bio-electricity? No one has ever proved that it flows throughout the body. But the brain operates by a combination of electrical and chemical means, as does the heart. Why not the entire body?

Acupuncture—inserting needles at various points to stimulate this bio-electric flow—has been shown to work. Chinese doctors have used it successfully to treat patients for many diseases. They’ve even used it in the place of anesthesia during major operations.

Many Western experts scoff at the notion of regulating this energy flowing throughout the human body. They feel that acupuncture, for example, works because of the power of suggestion: the Chinese expect it to work, so it does. But Asian veterinarians use it as anesthesia before operating on pets. Those Chinese sure have gullible dogs!

Other experts say that the existence of qi can’t be proven under laboratory conditions, hence it doesn’t exist. But what about the force known as gravity? No one denies its existence, yet no one ever has seen gravity or captured it in a test tube or beaker. But we measure its effects every time we walk across the lawn without being sucked up into the atmosphere, weightless.

When it comes to this energy known as qi, experience is the best teacher—you have to feel it operate in your own body. You have to see the puzzled looks on the doctors’ faces when your immune system and you should be as dead as the Hittites, yet the both of you are doing okay.

If it could be talked about, everyone would’ve told his brother.

But never mind qi. Look at the benefits from a Western point-of-view: the deep abdominal breathing calms the body and mind, provides more oxygen to the blood and better pumps the lymphatic system—a vital component of the immune system. Stretching and slow Qigong exercises are exercises one can do when, because of cancer/chemo fatigue, lifting weights or jogging is impossible.

People from the East exercise from the inside out, coordinating the mind, body, and breathing. They feel that a strong body starts with the torso, as most people eventually will die from organ malfunction, not from a problem with the arms or legs.

People from the West exercise from the outside in, using the mind and breathing in a rudimentary way, if at all. You get bigger muscles, but they don’t help much fighting disease. I never even thought about my internal organs and bodily processes. Facing my third bout with cancer, it was time I did.

THERE ARE DOCTORS….

Cancer, again, for the third time. Five years earlier Stage Four lymphoma cancer had appeared in my right hip and pelvis; six months of intensive chemotherapy eliminated it. Eighteen months later it relapsed in my left hip. Several months of chemotherapy and a bone marrow transplant at Beth Israel hospital in Boston eradicated it. A year or so later a tumor materialized in my right shoulder.

This relapse took my doctor, my family, and me by surprise. While normal chemotherapy treatments are like heavy artillery used to bombard the cancer, the chemotherapy used during the bone-marrow transplant I’d undergone was the equivalent of an atomic bomb.

Why should the cancer return if it had been eliminated by this nuclear blast? Why should it appear in my shoulder, instead of my hip/pelvic area, the original site of the disease? What is the sound of one hand clapping? No answers exist to these questions.

But the cancer had reappeared, in the early stages disguising itself as a sports injury of sorts. One day, after cutting some small trees from the pond’s edge behind our home, I felt a twinge in my right shoulder. The consensus was that the ache came from some type of tissue injury, perhaps a torn rotator cuff.

As the weeks passed, the pain intensified until I couldn’t lift my right arm. It felt as though a hive of angry wasps had been disturbed in my shoulder, repeatedly jabbing their stingers into the bone, pumping poison into my marrow. I gulped Tylox painkillers around the clock to take the edge off.

An MRI test detected a tumor, and a needle biopsy proved it to be malignant. Dr. N., my oncologist, was at a bit of a loss. People who relapse after undergoing a bone marrow transplant usually do not respond to additional chemotherapy.

Why? Apparently it’s survival of the fittest; the cancer cells that reappear are the ones most resistant to the treatment. They lurk somewhere in the body, dormant, a time bomb waiting for a fuse to be lit. One day the trigger’s pulled, they awaken and multiply with alacrity. The chemo drugs may have no effect, because these cells have developed a sort of immunity.

Dr. N. recommended another bone marrow transplant. She feared that the normal CHOP chemotherapy, already used earlier to fight my original cancer, would be ineffective. She called Beth Israel hospital in Boston to see if the oncologists would take me into their program for another transplant.

The Boston doctors refused even to interview me. They didn’t think another transplant would be successful, as the first procedure failed to cure the cancer. Apparently, there was nothing they could do for me. But I’d been told that before, at the time of the first transplant….

“…I don’t think there’s much we can do for you,” the radiologist from Boston had said, shaking his head and staring at the MRI picture of my left hip and pelvis. He had entered the diagnosis room a minute earlier, holding the MRI in his hand and staring at the floor as he slowly crossed the room to sit in the chair opposite me.

“But I don’t understand—they said I would be a good candidate for the transplant to work…” I stammered. It was the day before my first bone marrow transplant in Boston, and up until that point I’d been encouraged by both doctors and nurses.

“Maybe radiation after the chemotherapy could help—but there’s no guarantee. Of course it would have to be administered here in Boston….”

“You think that would do it?” I muttered, trying to collect my composure. “But why radiation here in Boston? My doctors in Hartford all were trained in Boston….”

“We’d have to watch your blood counts carefully and even then....” His voice trailed off, he sighed, got up from his chair, limply shook my hand and exited the room. Amazing: he hadn’t made eye contact with me the entire time.

That radiologist was like the doctors who recite statistics to patients: “As you can see on this multi-colored computer-generated bar graph, patients with your grade and stage of cancer have a life expectancy of three to six months” (apparently the attractively printed chart is meant to soften the blow).

For many patients, this news becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. They lose hope, become depressed, their immune systems shut down, and they make the doctor look like a genius. They die within his or her predicted time span. Do you think some of those doctors are getting good odds in Vegas?

Why can’t doctors frame the bad news differently? “You have a dangerous disease, but we have tools—chemotherapy, radiation, surgery—to combat it. People have beaten this disease. I can give you the names of a few that you can talk to. I’ll handle the medical treatments, but you have to be part of this by keeping a positive attitude.” That’s all we want, Doctors—no promises, no false cheer, no warm and fuzzy New Age horse-shit. Just a positive outlook and a glimmer of hope.

”…nothing they could do for me”—the brutal insensitivity of the radiologist from Boston two years earlier returned to haunt me, like the cancer itself. To hand out a death sentence the day before I began a bone marrow transplant! When I gathered my wits I called my oncologist at the Boston hospital and exploded in anger at the treatment I’d received: “You shouldn’t allow that guy to talk to flesh-and-blood people… you should lock him in his room with his X-rays and his isotopes and turn the machines on full blast!”

“Yes, he’s done this to other patients,” the oncologist agreed sympathetically. “It’s really unfortunate, but he’s part of our consulting staff. I wish he was more optimistic with people, but there’s not much I can do.”

Now, two years later, and this formerly sympathetic oncologist pronounces a death sentence over the telephone—not to me, but to my doctor. She wouldn’t even talk to me. She let my doctor do the dirty work.

Why? Admitting me for a second transplant would acknowledge that the first transplant did not work. Failure would adversely affect the hospital’s cure rate, which might affect future funding. It’s a numbers game, like any other business.

Those doctors did not owe me the right to further treatment, but they did owe me a face-to-face explanation. After all, I had endured the grueling schedule they set up for me: months of preliminary chemotherapy and testing, a month in the hospital for the transplant procedure, then more tests and follow-up visits. Several times I had had to wait over three hours for my appointments, nauseated and weak from chemotherapy treatments. Three hours! The Pope wouldn’t make sick people wait three hours.

But to the doctors at this transplant center, I was just an account number that showed up at the top of every billing statement, medical chart, prescription and computer screen concerned with me. Even the plastic ID bracelet I wore in the hospital listed my account number before my name.

AND THEN THERE ARE DOCTORS….

“Whatever happens, I’ll continue to treat you,” Dr. N., assured me. “Hang in there.” We had been through a lot together during the five years I had been her patient.

“Thanks, Doctor. I’ll hang—because if you’re born to be hanged, you should have no fear of drowning.” I recited Shakespeare’s bravado sentiment from The Tempest, but not with a great deal of conviction. She nodded, gave my bicep a gentle squeeze, and opened the door to the hallway.

I turned back to look at her and said: “You know, Doctor, it’s easy to appear macho about facing this disease… but when I think about what I have to lose—my wife, my children—I don’t feel so macho.”

Her gaze wavered ever so slightly. It seemed to me that her eyes filmed over. Mine did. In that instant her compassion fissured through the dam of professionalism she maintained to insulate patients from the knowledge of the severity of their condition, as well as to keep her sanity.

After all, this was cancer she was attempting to overcome, for me and a few dozen other patients. It was her job to break the bad news about negative test results; she had to deal with the desperation of disease relapses. Despite the best efforts of medical science, she had to watch patients wither from the combination of the disease and the chemotherapy and, often, die.

Then she had to go home and pretend it was just another day at the office. Why did she choose oncology, when she could’ve had a brilliant career in podiatry?

The next day Dr. N. called. The University of Connecticut Health Center would take me into its transplant program. The UCONN program entailed a rigorous, six-month protocol beginning with three four-day hospital stays before the month-long transplant. During these short hospital stays I would be bombarded with about the same amount of “atomic bomb” chemotherapy I’d received during my bone marrow transplant two years earlier in Boston. Then I’d enter the hospital for the actual transplant and the more lethal “hydrogen bomb” chemo.

In the meantime, she would treat me with the CHOP chemotherapy protocol (Cyclophosphamide, Hydroxydaunorubicin, Oncovin, Prednisone). We hoped it would at least control the spread of the lymphoma. With luck it would do more than contain the disease; it could plunge it back into remission. But the odds were against that.

“Zero doubt—I have zero doubt that you will beat this thing in the long run,” Denis Miller, M.D., said in his South African accent. He’d been our family doctor since my wife and I got married.

I was gearing up for my transplant, soliciting advice and support that would carry me through. Beowulf and his buddies, war masks on, would’ve smacked their shields with the flat of their sword blades to get their blood up. How little times change.

“Protoplasm, Bob,” he explained. “You have good protoplasm. And this lymphoma is beat-able—look at that Olympic wrestler who beat it twice. He’s fine now.”

Dr. Miller usually didn’t say much; he’d ask a question and fix a gaze like an X-ray on me while I spilled my guts. So when he talked, I listened.

“Besides, you’re a fighter, Bob. That will make the difference. I wish I could write a prescription for what you have inside, and hand it out to some of my other patients. Zero doubt, Bob.”

Zero doubt. Whenever the fear begins to take over, I’ll chant it, a new mantra. Maybe I’ll get it tattooed on my forehead. Zero doubt. Two words of encouragement from a doctor you respect—that’s all it takes to swell your courage. This guy wouldn’t lie to me. He’s a real doctor—and a friend. Besides, guys with X-ray vision don’t tell lies.

FINDING THE RIGHT TEACHER—SYNCHRONICITY OR COINCIDENCE?

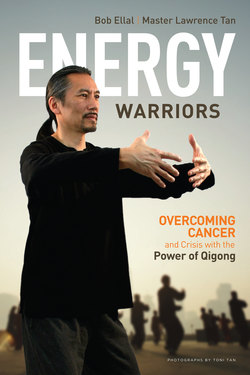

When the student is ready, the teacher appears. I met mine by happenstance. The same week cancer was diagnosed in my shoulder, a friend sent me a flyer advertising a Qigong seminar in Stonington, Connecticut. Ramel Rones—a disciple of renowned Kung fu, Tai qi chuan, and Qigong master Dr. Yang Jwing-Ming of Boston—was presenting an introduction on the value of Qigong in strengthening the immune system and the internal organs.

Maintaining my body’s immune system was vital to me; chemotherapy kills cancer cells, but it also damages the bone marrow, which manufactures the blood cells that comprise a person’s defenses against disease. The chemo also can wreak havoc on the heart and internal organs. Many people undergoing treatment die from the chemotherapy long before the cancer would’ve killed them.

Why torture myself with these mind/body exercises? Couldn’t I just take a bigger dose of painkillers, and hope the chemotherapy would destroy the tumor? Because I wanted to be part of the healing process—and have some control over my existence.

Control. Ha! Cancer is the ultimate state of a loss of control. Your body’s own cells mutate into mindless cannibals in full revolt against their host. Their mission? To be fruitful, to multiply, to eat away at healthy tissue and destroy the body that bore them. It is a kamikaze mission, because the cancer cells die right along with the body. Absalom, Absalom.

Ramel consulted with Dr. Yang, who developed a Qigong program to fit my needs. I practiced diligently, despite the pain. Every exercise, from the most basic stretch to the most sophisticated meditation, included the principle that the mind, breath, and body should be coordinated. In essence, you put awareness and intention into every Qigong exercise, so every exercise becomes a meditation.

During this time Dr. N. treated me with CHOP chemotherapy, which had destroyed the original cancer in my right hip five years earlier but wasn’t supposed to be effective for a relapse. Remarkably, it did seem to work, because after several months of treatment the pain disappeared from my shoulder.

The doctor sent me for a gallium scan, a nuclear medicine test, to assess the status of the cancer. Could the lump of lymphoma actually be gone?