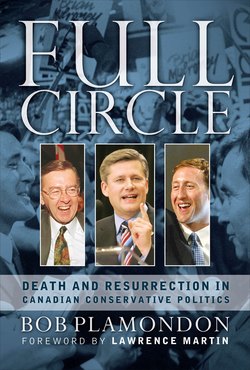

Читать книгу Full Circle: Death and Resurrection In Canadian Conservative Politics - Bob Plamondon - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

BRIAN MULRONEY

ОглавлениеAfter Sir John A. Macdonald, the next greatest conservative coalition builder is Brian Mulroney.

The son of Ben Mulroney, the chief electrician for Baie Comeau, Quebec, Martin Brian Mulroney was born on March 20, 1939, the third of six children. Brian shone brightly from an early age and was a natural leader and public speaker. He became active in politics at St. Francis Xavier University, taking the role of Conservative prime minister in its model parliament. While studying law at Laval, he was elected vice-president of the Conservative Students’ Federation.

Mulroney caught the attention of Diefenbaker and took on the unprecedented role of student adviser to the prime minister. David Angus, whom Mulroney appointed to the Senate in 1993, was a Young Progressive Conservative (YPC) colleague of Mulroney: “I met Mulroney at a PC convention when Diefenbaker was in power. Before I met him, Diefenbaker had talked to me about him. Imagine a sitting Prime Minister recognizing a student in that way. Brian was a magnet.” Mulroney faithfully supported the party’s efforts throughout the 1960s and early 1970s.While he had a national presence, his passion was Quebec, where electoral prospects for the Tories were weak to non-existent. By the time Robert Stanfield stepped down as leader in 1976, many in the party had identified Mulroney as a potential leader.

From his days in the YPC, Mulroney had an incredible network right across the country. However, his only link to the PC caucus was Patrick Knowlan, the MP from Annapolis Valley, Nova Scotia. The 1976 leadership convention did not go well for Mulroney: some refer to the movement to defeat the two business-oriented Quebecers, Claude Wagner and Brian Mulroney, the first- and second-place candidates on the first ballot, as the “great gang bang.” Mulroney was devastated. It was seven years before the position of leader came open again. During this period, Mulroney spent time licking his wounds, establishing a high profile and lucrative business career, and raising a family. He maintained his political contacts, including people such as Peter White, Frank Moores, and Sam Wakim—men who were anxious to oust Joe Clark as party leader.

What made Mulroney most distinctive to the party was that he was a Quebecer. Only once in its history had the Conservative party ever tried a Quebecer as party leader, and that was for only eighteen months at the end of the previous century.

Mulroney delivered what was, to that point in his life, his most important political speech on June 10, 1983, the day before party delegates would choose their next leader. The speech dealt not with policy and vision; rather, it was about the grand coalition that would bring Conservatives at long last out of the wilderness and into power: “Our major purpose... in being here is to drive the Liberals from office and bring about a majority Progressive Conservative government.” Mulroney called party unity a pre-condition to victory, and pledged to follow an eleventh commandment: “Thou Shall Never Speak Ill of Another Conservative.” Recognizing the breadth of conservatives represented in the party, Mulroney said, “There shall be no incivility because of divergent views... there shall be no ideological tests of purity, absolutely none.”

Mulroney boldly challenged convention delegates to face up to a historical reality: “Why is it that when we put on our hats as federal Conservatives... everyone says we are a bunch of losers?... [O]ur area of weakness in French Canada, time after time, decade after decade, election after election, has staggered this Party and debilitated the nation.” Invoking the memory of Sir John A. Macdonald and his coalition of west and east, English and French, Mulroney said, “Let us accept [Macdonald’s] invitation and let us recreate that grand alliance, and in the process, together we shall build a new Conservative Party and we shall build a brand new Canada.”

What Mulroney was really saying was, “elect me as leader and I will deliver seats from Quebec.” Given Liberal hegemony in Quebec, few believed this was possible. But Mulroney’s credentials were impressive and his confidence was brimming. His appeal to soft Quebec nationalists was unspoken, but very real and legitimate. The party could also verify Mulroney’s Quebec bona fides by the large number of Quebec delegates he brought with him to the 1983 leadership convention.

To win the leadership Mulroney built a cross-country network of support, but it was far from complete. He won the convention, but it took four ballots to do so, beating Joe Clark 54 per cent to 46 per cent. Mulroney reached out immediately to the other seven leadership contestants, all of whom represented different conservative constituencies. In his convention acceptance speech, he publicly indicated his desire to work with friend and foe alike. Erik Nielsen, the party’s interim leader, was at the podium after Mulroney had been declared victorious. Nielsen reminded the delegates that Mulroney had not been his first choice. Without missing a beat, Mulroney announced that Nielsen was his first choice as deputy leader. In that instant, Mulroney showed the discipline, wisdom, and grace that would inspire loyalty and draw the Conservative family together.

As a master coalition builder, Mulroney understood he could begin to unite his party by reinvigorating the failed leadership candidates. David Angus recalled that the day after the convention, Brian had lost his voice. “He called me into his suite at the Château Laurier and whispered, ‘I understand the party is in terrible shape. I want you to do an audit. We have to clean up the place.’ More important, the first thing he did, as party leader, was to make sure none of the candidates had a debt. There were some huge amounts owing, by Crosbie, Clark, Wilson, and others. We scheduled ten dinners across the country and we cleaned everything up. We built up a tremendous amount of goodwill among the candidates and in the party.”

Mulroney then turned his attention to party finances. “He didn’t want to go to the people of Canada to elect his party and him as prime minister if we didn’t have our own books balanced and if we didn’t have a frugal mindset,” said Angus. “We had to be able to present a responsible financial position, which we did.”

Mulroney recognized that his coalition had four distinct blocks. While he would deliver the Quebec contingent, he would rely upon deep conservative Atlantic roots, the free enterprise crowd from the West, and the “big blue machine” from Ontario. He counted on the provincial party machines to deliver the conservative vote in the regions of the country in which he was least familiar. “There were a lot of Tory Premiers to work with,” said Angus. “Premier Lougheed (from Alberta) was always supportive behind the scenes. But Quebec was the key to this thing. The Créditistes were no longer active, and Brian had a tremendous network in Quebec with an organization on the ground. We had organizers from the Quebec Liberal Party and the Parti Québécois. Brian seemed to know everybody.”

But Mulroney had a trump card that appealed nationwide: Canada was ready for a change.

Mulroney understood that for a party in opposition, coalition building could be a far-reaching and quiet exercise. In 1984, for example, it is unlikely that long-suffering Tory voters from the West would have thought of themselves as joining forces with soft Quebec nationalists. Conservatives in Quebec were too rare and unknown to be fully appreciated. This might help explain the surprise and disappointment of western conservatives when the Conservative government they had waited more than thirty years to elect stood for recognizing Quebec as a distinct society in the constitution.

While the Liberal party was choosing its new leader in the spring of 1984, Brian Mulroney and his wife, Mila, embarked on an extensive cross-country tour with little or no publicity in the national press. Mulroney dubbed this his “small town strategy.” It was unusual for party members to have a leader in their hometown except during an election. “I am leaving a series of pearls in all these communities across Canada. The moment that the new PM calls an election, the pearls will be strung together. Then just watch us!” This was Mulroney in action: reaching out to bring in new people. He made the newcomers feel they were part of a grand and noble coalition that would lead Canada to a brighter future.

Conservative provincial premiers were integral to the Mulroney coalition and to his 1984 summer tour. In the excitement of the tour, New Brunswick premier Richard Hatfield told Mulroney he was worried because up to six of his senior cabinet ministers confided they wanted to resign to run federally. Mulroney promised that he would only take two.

Mulroney inspired his coalition with his leadership style and engaging personal qualities: a legendary Irish charm, a wonderful capacity for storytelling, and an endearing if not unhealthy dose of loyalty. He was also a great campaigner, seizing a tremendous opportunity to deliver a knockout punch during the national leaders’ debates with Prime Minister John Turner on the issue of patronage.

To ensure a massive victory in Quebec, Mulroney delivered the now famous “Sept-Isles speech” that laid the groundwork for the Meech Lake Accord. Mulroney drew support from every quarter of Quebec. In some regions, he tapped into the Parti Québécois net- work for help; in other areas, provincial Liberals took the lead. It was a remarkable and unstoppable coalition that came to be known as Mulroney’s “Blue Thunder.”

Results from the 1984 election were better than even the most optimistic Conservatives could have imagined. Mulroney earned a popular vote of just more than 50 per cent; the first time a true majority in popular vote had been recorded in a Canadian election since the Diefenbaker sweep of 1958. By comparison, Trudeaumania in 1968 had produced a popular vote of 45.5 per cent, which was Trudeau’s best result as Liberal leader. Under Mulroney, Progressive Conservatives won 58 of 75 seats from Quebec. In the previous twenty years, Conservatives had never won more than 8 Quebec seats.

It was anyone’s guess how long the Mulroney coalition would last. In 1984, one leading columnist boldly predicted that Mulroney’s Conservatives had a lock on power until at least the turn of the century. However, building a coalition from the opposition benches was one thing. Keeping it together while in government was quite another.