Читать книгу Full Circle: Death and Resurrection In Canadian Conservative Politics - Bob Plamondon - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

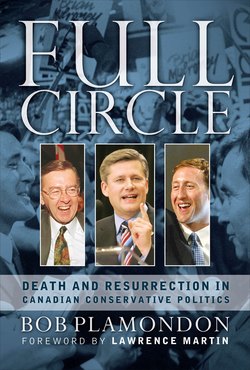

CHAPTER 4 MULRONEY LEADS CANADA, MANNING LEADS WESTERN DISCONTENT

ОглавлениеJoe Clark’s nine-month tenure as prime minister aside, in 1984 the federal Progressive Conservatives had not formed a government for a generation. Not since John Diefenbaker was last prime minister in 1963, twenty-one years earlier, had the Tories enjoyed real and lasting power. Brian Mulroney changed all that.

In the September 4, 1984 federal election, Progressive Conservatives took 211 out of 284 seats. It was a stunning and over- whelming victory that few predicted.

With such a huge majority, Mulroney was expected to transform government and the nation. The government moved quickly on a number of fronts to secure some easy wins to demonstrate that the direction of government had changed. It eradicated the much-hated National Energy Program (NEP) and repealed the Petroleum Gas Revenue Tax, issues of greatest concern to westerners. It replaced the restrictive Foreign Investment Review Agency (FIRA) with Investment Canada, which had a mandate to promote, rather than repel, foreign direct investment. It took steps to reduce government subsidies, and it identified Crown corporations for privatization. It steadily improved relations with Canada’s allies, particularly the United States. And it established a renewed spirit of co-operation with provinces that would ultimately lead to a unanimous agreement to amend the Canadian constitution. There was a litany of accomplishments that Mulroney could parade in front of conservatives and Canadians to demonstrate that his government was making a constructive difference.

Turning the nation’s finances around was another matter. To western Canadians in particular, dealing with the deficit was as much a sacred trust as protecting old-age pensions was to seniors. “The fiscal conservatives particularly in Alberta expected the Conservatives to balance the budget, reduce the taxes, and reduce the debt,” said Preston Manning. “When everything went in the opposite direction [Mulroney] just lost that whole constituency right there.”

But what was Mulroney’s record on the deficit? Did the Reform party happily exploit a myth, or did the PCs deserve rebuke for failing to balance the budget?

On entering office the Mulroney government faced a projected $42 billion deficit and a burgeoning level of public debt. While there is little doubt that finance minister Michael Wilson ushered in a new era of responsible financial management, progress on deficit reduction was slow, if not invisible.

Before Mulroney came to power, Liberal finance minister Marc Lalonde had seemed more concerned with putting the federal deficit into perspective than actually dealing with it. In April 2003, Lalonde wrote, “High interest rates and the recession have raised the federal deficit substantially. With the recovery expected to be moderate and gradual and with the international oil market outlook as weak as it is now, large decreases in magnitude of the deficit will not be easily achieved … I do not hold the view that the deficit must be brought down immediately…. There has been ample room for the federal government to finance the deficit without causing an increase in interest rates… The deficit must be brought down to lower levels as appropriate for the economy.” In other words, Lalonde was telling the country that dealing with the deficit was for some other finance minister at some other time.

Contrast the words of Marc Lalonde with those of Michael Wilson. In a document tabled in the House of Commons on November 8, 1984, barely one month after the change in government, Wilson reported, “For too long, the government has ignored the causes of the problems and has dealt only with the symptoms. For too long it has allowed the fiscal situation to deteriorate and the debt to increase ... we must put our fiscal house in order so that we can limit, and ultimately reverse, the massive build-up in public debt and the damaging impact this has on confidence and growth.”

The Liberal government saw debt as a tool to manage the economy. Wilson said that the deficit and the debt were the problem. When Wilson made this statement, government projections were calling for deficits over the ensuing four years to be in the range of $34 to $36 billion. In a November 1984 statement, measures were announced that would reduce government spending by about $4 billion in the short term.

Wilson’s first full budget came in May 1985. Actions were specified to reduce the deficit, including the de-indexation of various tax items and social payments. Under Wilson’s budget proposals, only increases in inflation beyond three percentage points would be automatically reflected in key elements of the tax and social security system. At the same time, to spur investment and job creation, the government announced a $500,000 lifetime capital gains exemption. The change in direction and policy from the previous administration was stark and clear.

Tough measures to control spending were coupled with an increase in tax revenue. (De-indexation was a method of increasing personal income taxes.). But the deficit was still projected to be in the range of $32 to $35 billion over the next few years. The actions might have seemed bold, but the results were modest.

Those who thought some quick-fix belt-tightening and a change from the big-spending Liberal ways would solve the problem were severely disappointed. Even with Conservatives in power there was no plan or reasonable expectation that the deficit would be eliminated in the foreseeable future.

Finance Minister Wilson wanted to lead on the deficit problem, but a number of people in the Mulroney government were not convinced Canadians were up for a stiff round of belt-tightening. Geoff Norquay, a PC party scribe and policy guru since 1981, was one of many who were frustrated by the government’s inability to persuade Canadians of the severity of the deficit problem in Mulroney’s first term as prime minister.

Norquay had been a leading backroom figure in the party for more than thirty years. His career in the policy field began with stints in the Ontario and Alberta governments. Before signing on with the PC Party, he was director of research for the Canadian Council on Social Development. When he was hired as research director for the PC party, he was interviewed by MPs who both sup- ported and criticized party leader Joe Clark. (Such was Clark’s command of the caucus in 1981, after the electoral defeat of February 18, 1980.) After the 1984 election, Norquay took on various responsibilities in the office of the prime minister, including speech writing and policy development. He “held the pen” for Jean Charest and the party during rebuilding efforts after the 1993 campaign and became a frequent commentator and panellist for the party in the national media. He served as communications director for Belinda Stronach in her run for Conservative party leader and for Stephen Harper when he was leader of Her Majesty’s Official Opposition.

Norquay contends that the government was way ahead of the public in its desire to tame the deficit. “People forget how just about every element of Canadian society vehemently and vigorously opposed doing anything about the deficit. The first response [to cutbacks] of the CBC was to publicly announce that the first thing they would do was to close the television station in Baie Comeau [Mulroney’s hometown]. There was controversy in the press that went on for months about killing a study on seagull eggs as part of cutting back. Just about every institution in Canadian society opposed what we were trying to do, including corporations. The Catholic church was at war with the government of Canada over social and economic policy. No one wanted to deal with this.”

As it was, the government did not hold firm on its plan to de- index old-age pensions. The change in position can be traced to a pledge made by Mulroney during the 1984 election, to treat government social programs as a “sacred trust.” The pledge was made in an attempt to quell fears that a Conservative government had a hidden agenda and would “slash and burn” government spending on the altar of the deficit. Mulroney comforted voters before the election by assuring them that savings would be found elsewhere in the system. Even hard-line western conservative John Weissenberger, a key figure in the creation of the Reform party who considered deficit reduction a priority, questioned the decision to target seniors’ programs. One event galvanized public opinion against Mulroney on the pension issue: an unplanned confrontation with a sixty-three-year-old Solange Denis, who was protesting outside Mulroney’s Langevin block offices. The prime minister was caught off guard when Denis said, “You made promises that you wouldn’t touch anything... you lied to us. I was made to vote for you and then it’s goodbye Charlie Brown.”

“We cut tail and ran,” said Norquay.

Despite the lack of visible progress on the deficit, by almost every objective measure Mulroney and Wilson had changed the course of government finances for the better. The problem for Conservatives was that it took expertise on government finances to understand what they had accomplished.

Governments are like oil tankers: very hard to turn. In fact, most government spending is subject to long-term commitments that make it difficult to institute any sort of quick fix. In 1984–85, 23 per cent of all spending was on interest. The government could hardly reduce spending by repudiating its debt. About 22 per cent of all spending was payments to individual Canadians for universal social programs: Old Age Security, Unemployment Insurance, and Family Allowance. The “sacred trust” promise made it difficult to reduce these costs. Besides, Canadians would only be prepared to cut payments to individuals once they were satisfied that government waste and inefficiency had been addressed. Transfers to provincial government for health care, education, social assistance, and equalization amounted to about 17 per cent of all spending. (The Mulroney government had no mandate to cut in this area.) Other transfers amounted to 13 per cent of spending. National defence accounted for 7 per cent and Crown corporations almost 6 per cent of all government spending. That left about $12 billion for all other government departments and agencies, about 11 per cent of the total. The pool of $12 billion is what Canadians thought could be trimmed to resolve a $40-billion deficit. Those who thought that cutting out the waste and inefficiency in government operations would eliminate the deficit had limited insight into the nature of government spending.

The Conservative plan to reduce the deficit had three elements. First, a growing economy would produce higher revenues. Second, program spending would be limited to increases at or below the rate of inflation. Third, selected spending cuts would be made in low- priority areas. Taken together, these three elements would slowly strengthen government finances without causing any great shock to the economy. The plan was incremental, and not exciting.

Holding spending increases to the rate of inflation might not seem particularly ambitious, but it would be a Herculean achievement given what had transpired in the previous two decades. From 1968 to 1984—the Trudeau years—the average increase in program spending was 13.1 per cent per year. In the early and mid-1970s, the average increase was more than 17 per cent per year. The record year was 1974–75. It was just after the NDP propped up the Trudeau’s minority Liberal government that program spending increased by a whopping 27.9 per cent. Out-of-control spending and persistent deficits took their toll on government finances. During the Trudeau era, Canada’s national debt increased tenfold, from $19.2 to $194.4 billion.

During Wilson’s first year as finance minister, program spending decreased by $800 million, or 1 full percentage point. The reduction was modest but nonetheless earth-shattering: the brakes on spending had clearly been applied. In the first four years of Conservative administration, program spending increased on average 3.8 per cent, one-third the level of the increases of the previous administration. Relative to the size of the economy, program spending in Mulroney’s first term declined from 18.5 per cent of GDP (gross domestic product) to 15.7 per cent. Had government spending maintained the same share of the economy during Mulroney’s first term, the size of the deficit would have been at least $17 billion higher than was ultimately recorded.

Spending control is only one side of the deficit equation, although this was clearly the side that most Canadians wanted the government to pursue. Nonetheless, government revenues increased during Mulroney’s first term by some $33 billion, rising from 15.7 per cent to 16.9 per cent of GDP. Economic growth was the primary reason for higher revenues, although the government also imposed “temporary” surtaxes and the de-indexation of various tax elements to help bring the deficit down.

All this left Canadians confused. Revenues were rising, the government talked about being tough on spending, but the country was still plagued with huge deficits. The problem, which most Canadians did not understand, was the debt.

To help understand the burden of debt, it is worth looking at what happened to government operations from the 1960s to the 1990s, excluding interest on the accumulated debt. For most of the 1960s, the government had healthy operating surpluses, with revenues exceeding program spending by more than $5 billion. In the 1970s, the federal government spent $16.3 billion more on programs than it received in revenues. This meant that for an entire decade there was no residual revenue to pay the interest on the debt. In other words, Canada borrowed every cent needed to pay the interest on the debt. In the early 1980s, before Mulroney came to power, operating deficits totalled $36.9 billion. In 1984–85, the operating deficit was $12.2 billion. By the end of Mulroney’s first term, that operating deficit had been converted to an annual surplus of $7.6 billion, a turnaround of $19.8 billion.

Despite remarkable improvements in the operating position, the deficit by the end of Mulroney’s first term remained stubbornly high, at $27.9 billion. The big financial problem was the debt. The government tried to claim some success, citing that relative to the size of the economy, the deficit had shrunk almost in half, from 8.3 per cent to 4.6 per cent of GDP. Yet it was easy for opponents of the government to ridicule any boast of progress, as the overall debt load during this period had risen from $194 billion to $314 billion, an increase of 62 per cent. Relative to the size of the economy, the debt rose in each year of Mulroney’s first term, from 43.2 per cent of GDP in 1984–85 to 51.3 per cent in 1998–89.

Relatively high interest rates, designed to combat inflation, exacerbated the problem of the debt. The average interest rate on Canada’s outstanding debt during Mulroney’s first term was 11.6 per cent. Compare that with the rate for 2004–05, which was

6.8 per cent, a difference of almost 5 per cent. Such a difference on a $314-billion debt in 1988–89 would have produced a dramatically different bottom line. But the government and the people wanted a balanced budget, and not even the most optimistic forecaster could predict a balanced budget over the short or medium term.

The Mulroney government deserves substantial credit for making significant progress in turning the finances of the nation around. It took control of government spending, limiting increases to below the rate of growth of the economy. It brought in more money from a growing economy and from selected tax measures. It turned a $12.2- billion operating deficit into a $7.6-billion operating surplus. Had the Mulroney government, throughout its first term in office, maintained the previous Liberal government’s relative level of spending and taxation, the deficit would have been more than $60 billion. Because of the debts in place when Mulroney took office, the best it could accomplish at the end of its first term was to reduce the deficit to $29 billion. Canadians, and western Canadians in particular, were not impressed. It was hard for Mulroney to explain to even the most sophisticated observers that such a deficit was an accomplishment.

Certainly Preston Manning was sophisticated, and he understood government finances. But Mulroney’s accomplishments were of little consequence to Manning. Future deputy prime minister Don Mazankowski could see that: “Manning was always organizing something.” From his writings and activities, one could conclude that Manning was inclined to be unimpressed with Mulroney even before he was sworn in as prime minister. Some might go so far as to say Manning wanted Mulroney to fail. If Mulroney and his massive majority could not deliver the sort of government demanded by western Canadians, suggested Manning, then maybe the country needed an alternative. His alternative.

Most westerners could readily list their disappointments with the Mulroney government’s first term: patronage abuses, political scandal, perceived slowness in responding to western grievances about the National Energy Program, and even the government’s general sensitivities towards Quebec. The much-hated deficit was enough to make western blood boil. But even these issues, taken together, were not enough for westerners to turn on the new Conservative government so early in its mandate. There was not yet enough of the groundswell Manning was looking for to launch a new political movement. But that did not mean Manning was not trying.

At a meeting on October 17, 1986, Manning made the case to some senior oil industry executives “for a new federal political movement dedicated to reforms that would make the West an equal partner in Confederation.” It was a speech Manning had been delivering in his mind and in public for the past twenty years. Manning expressed his view that the West would produce something new provided it had the leadership and funds to do the job. Not everyone was convinced. Manning remembers, “One of the people in there was a pollster, David Elton, who at that time was head of the Canada West Foundation. I used him as a pollster in some of my consulting work, and he was intimately familiar with polling data, particularly in Western Canada. David was sympathetic to what I was saying but said, ‘Look, my heart is with you but my head will tell you that there is absolutely no proof in the polling data that there is a market for a new political party of any kind in Western Canada.’” While there was agreement at the meeting that a gathering of like-minded westerners would be a good start for a new political movement, they realized they still needed a spark to fan the flames of discontent. That spark came not more than two weeks later, ironically on Halloween.

On October 31, 1986, the Mulroney government announced that a maintenance contract for Canada’s CF-18 fighter jets was being awarded to Canadair of Montreal, Quebec. This award overruled the recommendation made by a panel assembled to evaluate competitive bids. The panel had determined that Bristol Aerospace Ltd. of Manitoba had submitted the superior technical and financial bid.

The decision by the Mulroney government was not just about economic development for Quebec; it was hardball politics. Politicians from Quebec had lobbied Mulroney, who wanted Quebec to be happy. In the five elections before 1984, Conservatives had won only 12 out of 372 seats contested in Quebec. Mulroney wanted to show that electing 58 Tories from Quebec in the 1984 election had made a difference. With no political roots in Quebec, the Tories were anxious to build something that would last into the next election and beyond. Shaun Masterson worked in the Prime Minister’s Office at the time. “It was clear from the discussions that this would be controversial. But our coalition in Quebec had no roots, and we were trying to build something that would be sustainable.”

Mulroney knew a “Quebec Round” of constitutional talks lay ahead. One of his key election planks was to have Quebec sign the Canadian constitution with honour and dignity. If he was sensitive to Quebec’s need for economic development, the constitutional talks might go that much easier.

Mulroney was mindful of the large number of companies that had fled Quebec in 1976 when the sovereignist Parti Québécois was elected. He wanted to reverse that trend and be able to point to some success stories that would spark the attachment of Quebecers to Canada. He argued that his decision to award the contract to Canadair was in the national interest because the technology embedded in the CF-18 contract would be used by Canadair to create manufacturing jobs in Canada. According to Don Mazankowski, “The guys in Winnipeg had no use for that technology. The issue that the government had to wrestle with was what became of the technology; who could make best use of the technology. Most public servants in the Defence department said it was the right decision in terms of insuring that the technology could be utilized in the most effective way.”

Mulroney concedes his government suffered from the CF-18 decision because of a tremendous failure to communicate effectively the reasons for the decision. As a consequence, the feelings of western resentment towards Quebec, which had until then been kept just below the surface of public discourse, were legitimized. Preston Manning could capture and exploit the anger over the CF-18 decision to build the movement he had been hoping to lead.

Communication specialists in the Prime Minister’s Office knew the decision was trouble. “I was very much in the minority in warning anybody who would listen about the hugely damaging consequences of the CF-18 decision,” said Geoff Norquay.

The process by which the government made its decision was never explained, but it would be logical to conclude that Mulroney made the call on his own. Norquay recalls, “I went to the Priorities and Planning Committee and to full cabinet for four years and I don’t recall any discussions about the CF-18 issue.”

When one region of the country feels it has been harmed by a government decision, the government often tries to help in other ways. “Little is known about the CF-5 contract that went to Winnipeg that same year. It was a bigger dollar figure than the CF-18 contract,” said Mazankowski.

But Mazankowski was also realistic about what the CF-18 decision meant. “I knew it would be trouble. I knew it would be a difficult sell.” Speaking of its impact on Preston Manning’s ability to build and mass forces with the Reform party, Mazankowski said, “The CF-18 decision didn’t help. That was an issue that gave Manning’s movement momentum.”

So Quebec might have been happy, but the West was outraged. Some groups, such as the Western Canada Concept, talked openly of separation. “That is just one of many insults to the West which can- not be effectively answered by the present federal political parties which are directed from Central Canada. The Canadair contract was a billion-dollar bribe to the voters of Quebec and demonstrated once again that Western separatism is justified.”

The CF-18 decision reaffirmed what many Canadians thought about federal politicians: they favoured Quebec over other parts of

Canada. In a late 1986 poll by Environics Research, 67 per cent of those surveyed expressed the view that the federal government favoured one region and did not treat all regions fairly. In the West, 83 per cent held this view, and Quebec was identified as the number-one beneficiary. The poll also revealed a serious decline in Tory support in Western Canada. The poll pegged Conservative support at 35 per cent, well below the 69 per cent the Tories had received two years earlier from Albertans in the general election. Westerners were saying that not much seemed to have changed between Liberal governments of the past and the Conservative administration of the present.

Manning knew that the CF-18 decision was a gift:

It was a significant contract in its own right, but it was the symbolism of it all. The West felt the Liberals always bent over backwards to accommodate Quebec and didn’t even hear what the West was saying. Here were the new guys, the different guys, the different guys who were going to do it different, doing exactly the same thing. They made a big thing about having western guys in the cabinet, but then they send [Manitoba MP and minister of national health and welfare] Jake Epp back to Winnipeg to try to convince Winnipeg that this somehow was in the national interest. This just added insult to injury. I think there were enough other ingredients [to launch Reform]. The CF-18 thing had its biggest impact in Manitoba, although it was seen as a symbol across the West. I think the biggest driver was still the fiscal thing. But the CF-18 was icing on the cake.

David Angus thought the reaction of Manning and others in the West to the CF-18 was excessive:

Mulroney was focused on separatism in Quebec and he told the western group to run the country. Mazankowski was the chair of the cabinet operations committee, which was a new thing that Mulroney had invented. No matter what Mulroney did to help the West, all they would remember was the CF-18 decision. We were getting out of that business. Canadair had been disadvantaged because they had to swallow de Havilland. They were the beginning of Bombardier Aerospace. But it was a symbolic thing. We gave Manitoba way more compensation for not getting the contract. Why was it that the CF-18 decision became the only thing? They said we were anti-west and that was just plain wrong.

While few can recall how the CF-18 decision was made, or discussing it beforehand, the announcement certainly caused a commotion in the Tory caucus. Gerry St. Germain was PC caucus chair at the time: “I don’t recall much discussion about CF-18 before the decision was made, but it definitely caused an uproar in caucus. It was the symbolism of the thing, another sop to Quebec at the expense of western Canada. It was the only time I ever agreed with Norman Atkins. We both told the prime minister at the time that it was the wrong decision.” St. Germain believes the CF-18 decision was historic. “I knew most of the founders of the Reform Party, many of them former RCMP. I asked them, ‘What was the one factor that caused you to join Reform?’ CF-18 comes up ten times out of ten.”

There had been talk of separation in western Canada before. Various attempts had been made in the 1970s and early 1980s to launch western-based protest parties; most of the attempts used Pierre Trudeau as their punching bag. Many promptly flamed out, usually because of their extreme positions or because of the suspicious characters involved in their formation.

Manning would have nothing to do with these protest movements. He sought a far-reaching and overwhelming populist wave of discontent. Also, significantly, he did not argue for separation: he wanted a “New Canada.” Why did Manning, a man of clear conservative persuasion, not seek to enlighten Mulroney and his western cabinet ministers of the error of their ways? Why, with Mulroney in office for only a few short years, did Manning not seek to reshape the Progressive Conservative party? Because this approach ran counter to his political strategy. Manning wanted to work from the outside. He was more comfortable protesting and agitating than governing. He wanted to lead a grassroots mainstream protest party that would shake up the political elite. Timing was critical to the launch of his new venture, and it took patience: “... rather than getting on the tail end of the populist movements produced on the Canadian prairies during the depression, I would wait for the next one. By 1986, there were signs that another populist movement was in the making in western Canada.”

It is ironic that Manning, a conservative, had to wait until the Progressive Conservatives were in power for his protest party to take hold. Trevor Harrison, a professor of political science at the University of Alberta, observed the incongruity of the rise of right- wing populism and the Reform Party of Canada coinciding with the election of a Conservative government: “Within a short time, the Tories dismantled state-nationalist economic policies, decentralized political authority and control, and generally followed a pro-business agenda. What was the effect of this political change upon the western region... ironically right-wing populism gained in momentum!”

Manning believes that Liberals have generally been better than Conservatives at responding to western grievances. “Whether Mulroney had behaved differently, or if Trudeau had behaved differently, maybe Reform wouldn’t have happened, or more likely it would have happened fifteen years later. The traditional parties are just slow-moving anyway. The success of the traditional parties, to a large degree, depends on their ability to recognize these movements and accommodate them—or fails to recognize them and accommodate them. In the twentieth century, the Liberals have been more the ones who have picked up these movements and tried to accommodate them. The Conservatives have been slower at it.” Nowhere in this statement does Manning talk about governing. Shaking things up seems to be his goal.

Manning knew that the CF-18 decision engendered mistrust and disappointment that cut a wide swath across the western electorate. Resentment of the Progressive Conservative government in western Canada was at an apex. Mainstream westerners could no longer simply blame the Liberals. Manning knew that westerners were hungry for a legitimate and credible voice that could articulate western resentment. He remarked, “The hotheads talked about separation; cooler heads sought better alternatives, but the conditions for a full- blown prairie fire were present. The time for ‘waiting for something to happen’ was over. Something was happening. It was time to act.” The Reform party was not the brainchild of disgruntled Progressive Conservatives. The origins of Reform can clearly be traced to the latent forces of the Social Credit movement. Like Reform, the Social Credit party had clear western roots. It was formed in the early part of the twentieth century in western Canada to combat the more powerful industrial class of the East. In Alberta, Social Credit governed from 1935 to 1971, principally under the leadership of premiers William Aberhart and Ernest Manning. Beginning in 1952, Socreds governed British Columbia for thirty-six of thirty-nine years.

Federally, the Social Credit party has existed since 1935. In the early 1960s it held as many as 30 seats in the federal Parliament, consistently ranking ahead of the New Democrats. The last time Social Credit or Créditistes had members in the House of Commons was during the short-lived thirty-first Parliament led by Joe Clark.

The 1979 election left Clark only 6 seats short of a majority government, precisely the number of seats held by Social Credit under the leadership of Fabien Roy. On the fateful night of December 13, 1979,a vote of confidence was held on the Clark government, and Social Credit members either abstained or failed to show up for the vote. It would have taken very little effort on Clark’s part to gain the sup- port of the small Social Credit caucus, but he had decided to run his government as if he had a majority, and he ignored the otherwise “conservative” Social Credit MPs. In effect, Social Credit defeated the government. As Elmer MacKay recalls, Clark was not concerned about bringing the Socreds on side. “We could have won them over by giving them a few perks in office and by increasing their profile. And as a guy who likes to win, I told Clark we should make common cause with Socreds. They were not difficult people to deal with. But Clark thought it would be like Diefenbaker in 1958; going from a minority to a huge majority.” History shows that Socred members would regret their decision to defeat the Clark government, as they have not held a seat in Parliament since. Many people remember the legacy and the glory days of Social Credit; no one more so than Preston Manning.

Manning and many of his followers were influenced by the writings of Peter Brimelow, especially his 1986 book The Patriot Game. The essence of the “patriot game” is to use the fear of Quebec’s separation as an excuse to control the national political agenda, largely to the benefit of a class of mostly Liberal political elites. Brimelow predicted in the book that new splinter parties would emerge, that the fate of Confederation was anything but certain, and that elections would take the form of Russian roulette.

It was somewhat unexpected for a populist free-enterprise prairie politician to lead on issues related to Quebec. But Manning was a dedicated historian with a passion for the country’s constitution and the rule of law. He was also brave and not worried that he might be criticized for speaking out. While most observers would say that Reform was able to flourish because of Mulroney’s perceived inadequacies, Manning gives the initial credit for the Reform revolution to another Quebec politician. “Trudeau laid the seeds for separatism... by insisting that the federal government, and not the Quebec government, be the guardian of the French language and culture. He was on a collision course with Quebec nationalists [for that], plus from the way he repatriated the constitution.”

Manning signalled that the day of the realignment of the conservative political movement was pending. In the book he and his father researched and wrote, ominous counsel was offered to conservatives under the heading “Consideration of One Remaining Alternative”:

Anyone who speaks or writes about the subject of political realignment is open to the common misinterpretation that he is advocating the formation of another political party altogether apart from those presently in existence. I wish to make it very clear that this is not what I am advocating in this thesis. I do not believe that the formation of an entirely new political party is the best way to meet the serious national political needs of the present hour. Nevertheless, having regard to the prevailing political mood of the Canadian people, present national party leaders and federal politicians, especially those affiliated with the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada, should take cognizance of the following fact: if the Canadian political situation continues to degenerate, and if the cause of conservatism continues to suffer and decline, not for lack of merit or a willingness on the part of the Canadian people to support modern conservative principles or policies, but rather because of unnecessary dissention among politicians and par- ties, the idea of establishing a wholly new political party committed to the social conservative positions will find an ever increasing number of advocates and supporters among a concerned and aroused Canadian public.

The establishment of Reform was the fulfillment of that prognostication. The brand of conservatism Mulroney offered failed to meet Manning’s conditions for not organizing a new political party. To Preston Manning, the Mulroney government had fallen into Brimelow’s Patriot Game and was ignoring western concerns: “The Mulroney Conservatives tried to accommodate the Quebec bloc by making his [Mulroney’s] own deal with the nationalists. He hoped that things like Meech Lake would accommodate them. But I don’t think Mulroney ever understood the western movement. There wasn’t much of an attempt to accommodate it.”

Preston Manning and Stephen Harper shared a distrust of and disappointment in the Mulroney administration, but they came to this common conclusion from different perspectives. Manning expected Mulroney to fail, perhaps even hoped he would fail, while Harper was filled with enthusiasm after helping Tory MP Jim Hawkes get elected in 1984. Manning scrutinized Mulroney’s actions, looking for a political opening for himself and a western-based populist movement; Harper travelled to Ottawa to work as Hawkes’s legislative assistant. Then Manning’s and Harper’s views began to converge.

Ottawa did not impress the young Stephen Harper. It was relatively early days in the Mulroney administration, and Harper began his year-long sojourn with high hopes for a fundamental conservative transformation of the workings of government. He hoped to find Parliament a place of ideas, debate, intellectual stimulation, integrity, and respect for the taxpayer. Instead he discovered a phony environment filled with trivial and meaningless chatter and policies designed not to offend the masses. Harper had no interest in playing the Ottawa game of glad-handing and networking. While others went to restaurants and bars, he went to the parliamentary library. The keen young conservative had set his sights on reforms to the unemployment insurance program.

Like almost every intern who works as a parliamentary assistant, Harper told his boss that he had no interest whatsoever in seeking elected office. But many interns who make such a statement are hiding personal ambition, and if they get the chance to seek elected office they will take it. Harper is a case in point.

Harper saw Conservative leadership that meekly compromised in the name of a broader coalition as a failure. Fed up and lonely, he returned to the University of Calgary to pursue post-graduate studies. He was not entrepreneurial or particularly motivated by money; he was a man of ideas, an intellectual who could easily have pursued a comfortable life as a university professor. As Jim Hawkes said: “Everyone thought his future lay in proceeding to a doctorate in economics and to a career in university, something that would also give him the opportunity to advance policy ideas.”

But Harper was still very much a partisan and wondered how he could help persuade Mulroney and the PC party to shift to the right and follow a purer form of conservatism, like that being pursued by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. Harper felt there was not much cause for optimism in this mission; in his view, the Red Tories, those in the middle and perhaps the left of the political spectrum, were in charge of the PC party. In his view, the leadership of the party lacked political will. Nonetheless, his first instinct was to work within the PC party to try to move it to the right of centre by building a “Blue Tory” network.

“The Blue Tory network was basically two guys: Stephen and me,” recalled John Weissenberger, a colleague of Harper’s at the University of Calgary and the man considered to be Harper’s best friend.18 Like Harper, Weissenberger was an easterner who went west in the early 1980s to pursue studies and a career. Harper and Weissenberger met while they were volunteers for the Calgary West PC Association in 1988.

“The idea behind the Blue Tory network,” said Weissenberger, “was to find a home for philosophical conservatives, who did not exist at the time within the PC party. There was not, to our minds,

strong philosophical base to the party, especially compared with what was happening to conservative parties around the world. The PC party, in our estimation, was a very broad brokerage party that was trying to copy the Liberal party in terms of its positioning within the political spectrum.”

Weissenberger and Harper developed terms of reference for their Blue Tory network and identified caucus members they thought might support it. “These were the caucus members that to average PC members would have been referred to as the dinosaurs,” said Weissenberger. “But what we really wanted to attract was younger people to the cause.” In the 1980s, there was no Internet or blogging; communication and outreach were more painstaking.

The dinosaurs had another name for themselves: the 1922 Club. According to Gerry St. Germain, the club was patterned after a rump of the Tory caucus, formed in 1922 in Great Britain out of a huge majority government, not unlike the one Mulroney had earned in 1984.The Canadian version of the 1922 Club consisted mostly of western members with strong right-wing social conservative views on issues like capital punishment. Mulroney acknowledges that he had “Reformers” in his caucus. However, once inside caucus expo- sure to the legitimate interests and concerns of members from other parts of the country persuaded most of them to accept a more moderate and inclusive national vision.

It is clear that Harper and Weissenberger wanted to remain politically active, and their first choice was to work within the structure of the existing system, that is, the PC Party of Canada. It is equally clear that Harper did not underestimate the challenge of remaking the PC party from within. Within the party, he and Wiessenberger would have been but a couple of faint voices. While they may have been accused of being dogmatic and youthfully uncompromising, they understood they were in a “big tent” political party that was sup- posed to represent a broad spectrum of political views. The problem, as they saw it, was that small-c conservatives were essentially ignored or, worse, derisively labelled as right-wing Neanderthals. “There is a difference between being a conservative and making honourable compromises, and being a centrist,” said Weissenberger. “ A lack of conservative philosophical grounding caused the PC party to be not much different from the old Liberal party.”

Weissenberger added, “But the whole Blue Tory network thing got short circuited.” That’s because Robert Mansell, head of the economics department at the University of Calgary, introduced Stephen Harper and John Weissenberger to Preston Manning. This was no chance introduction: Manning had asked Mansell for his best and brightest student, and Mansell thought of Harper. He was, recalled Mansell, “A reluctant politician—an ideal politician in my sense.”

To both Harper and Weissenberger, Manning sounded like a principled conservative; he had credibility in the West, was articulate, and was prepared to give two young and inexperienced conservative idealists a chance to spread their wings. Manning could provide an easier route for the University of Calgary students to hatch their network. “Had we carried on with the Blue Tory network [within the PC party], we would have been going against the party establishment. We would have been going against the flow. We were willing to work inside the party to try and change things, but it seemed to us the path of least resistance was to leave and try and effect change from the outside,” said Weissenberger.

Harper and Manning both felt that something was wrong in Ottawa. Harper was intrigued with Manning and travelled to Vancouver to attend an assembly Manning helped organize. Prime Minister Mulroney had directed the PC party to avoid the assembly. But Harper and Weissenberger felt no disloyalty in attending and contributing. “I get annoyed when... Stephen and I are called turn- coats and traitors for leaving the PCs,” said Weissenberger. “We did not leave for any personal advantage and had no expectations of personal gain. We went into the wilderness and filled a void. We just thought it was the right thing to do and we did it.” The meeting would lead to the creation of a new political party that would change the course of Canadian history.

The Western Assembly on Canada’s Economic and Political Future was held in Vancouver May 29–31, 1987. Under the banner “The West Wants In,” about three hundred delegates and observers discussed issues such as regional fairness, balanced budgets, Senate reform, and free trade. Progressive Conservatives thought the West was already “in.” After decades of underrepresentation during the Trudeau years, western conservatives filled the government benches and cabinet seats like never before. Yet it was not western people Manning wanted in, it was popular western ideas. The assembly was no meeting of flaming radicals. The creation of the Reform party was careful, deliberate, thoughtful, and professional.

To establish an organized response to western alienation, four options were debated: (i) work with a traditional party; (ii) create a focused pressure group; (iii) create a new federal political party; and (iv) the non-offensive category “other.” While there were four options on the table, however, the outcome was never in doubt. “Preston had the objective right away of forming a political party that he would lead,” said Weissenberger. “It is a fair comment to say that this was his objective back in 1967.”

Preston Manning and others tried to argue that the new political party would be different and would not be ideologically focused. Trevor Harrison, in his book on the rise of the Reform party, paints a different picture. “Despite Manning’s call for balance, the ideological mix of the new party had already begun to congeal around certain right-wing principles.” Harrison cited comments from delegates and reporters to support his conclusion that assembly participants “were almost uniformly social and economic conservatives” who were “dominated by old-time Socreds dying for another kick at the political cat.”

The young Stephen Harper went to the assembly with a manifesto called “A Taxpayers Reform Agenda,” which he concocted with Weissenberger. Their agenda included eleven one-sentence proposals that were true to conservative principles. But Harper’s right-wing perspective was at odds with the message Manning delivered to the assembly. Manning advocated a populist movement that would, in theory, appeal to the left, middle, and right of the political spectrum. He may have sounded like a conservative when he complained about the Mulroney government being out of touch with western Canada, but he was not trying to form a party of the right. Manning, an evangelical Christian, also spoke of social conservative issues, which were nowhere to be found in Harper’s manifesto.

Despite Manning’s populist urgings, Harper felt he was among true conservatives, and he was comfortable enough to abandon his Blue Tory project to explore what could be done within this new western-based political movement.

The convention that established the Reform Party of Canada took place in Winnipeg from October 30 to November 1, 1987.The 306 delegates were largely from Alberta.

Manning thought Stephen Harper’s speech, titled “Achieving Economic Justice in Confederation,” was the best of the convention. He credited Harper with “. . . shatter[ing] all the stereotypes (reactionary, backward looking, narrow, simplistic, extreme) that are often applied to a new political party struggling for legitimacy from a western base.” Harper demonstrated the extent to which the West gave far more than it received within Confederation. Whether it was transfer payments, regional economic development, unemployment insurance, government employment, or tariff protection, the West was consistently on the short end of the stick. Power, Harper suggested, was concentrated in the hands of eastern elites who sought to perpetuate the welfare state and seek appeasement from Quebec. Those agitated because the CF-18 maintenance con- tract was given to Quebec-based Canadair, whose bid was higher and whose technology was inferior, instead of to western Canada’s Bristol Aerospace, had a cogent and articulate framework in which to situate their anGST. No longer, Harper argued, should the country “…be built on the economic exploitation and political disenfranchisement of western Canada.”

With the theme “The West Wants In,” Manning believed he was laying the groundwork for a national political party. He recalled, “When Reform started, one of the first discussions we had at the founding convention in Winnipeg was, are we creating a regional party or creating a national party? I argued we were creating a national party. We might have to start in one region because that’s where we had our roots and our energy, and we had only very limited resources.”

The party was founded on principles of openness and inclusiveness, but the process to elect a leader was anything but. Manning faced Stan Roberts, the former president of the Canada West Foundation and Canadian Chamber of Commerce, for the leader- ship. Delegates were to be registered by Saturday, but the registration was closed early. Trevor Harrison, in Passionate Intensity, described the scene:

As the crucial vote neared, tensions between the two camps increased. Fearing that the Roberts camp was about to bus in a number of “instant delegates,” Manning supporters closed dele- gate registration on the Friday evening. [Frances] Winspear, who was supporting Roberts, stood up before the delegates and denounced the decision to suspend registration. This incident was followed by further accusations from Roberts that association moneys were unaccounted for . . . Roberts made a brief emotional statement to the delegates, announcing that he was withdrawing from the race. “It is with deep regret,” he said, “that I have taken this step…This party was founded on the principles of honesty and integrity—those principles appear to have been compromised during this convention.” Declaring Manning’s supporters “fanatical Albertans” and “small-minded evangelical cranks,” Roberts then stormed out of the convention.

Of the fracas that ensued, Manning remarked, “[The] delegates seemed pleased with the results. That was all that really mattered.” This statement seems inconsistent with Manning’s approach to other issues. When asked to explain his objection to the Meech Lake Accord, Manning pointed to the objectionable process under which the agreement had been reached.

University of Calgary professor Tom Flanagan was an adviser to Manning and has described Manning’s inner thoughts and strategies. In his book Waiting for the Wave: The Reform Party and Preston Manning, Flanagan provides a somewhat surprising assessment of Manning’s controlling leadership style. He argues that Manning led the nomination process for the party’s executive, dealt with staff “one-on-one” to diminish their ability to override the leader by sheer numbers, and controlled the formulation of policy. It was an anomaly that a populist party, designed first and foremost to represent its members, was tightly controlled by one individual. Said Flanagan, “To a remarkable degree, the Reform Party is the personal project of Preston Manning.”

Preston manning believed that the Reform party crossed all political lines and appealed to masses of Canadians who were disillusioned with the traditional political parties. Manning’s Reform party would, in theory, draw support from the mainstream parties in roughly the same proportions as these individuals would other- wise have voted. But was Reform a populist party, as Manning claimed, or was it intrinsically conservative and in direct competition with the Progressive Conservative party?

Manning did not want to accept that Reform was really another Conservative party, because he did not want to debate an inherent and obvious strategic flaw: that the Reform party was splitting votes with the Tories and thereby electing Liberals and NDP members of parliament. Manning also did not want to be accused of cannibalizing the vote on the right. Manning may have hoped the votes had not been split, but the results are indisputable. Stated differently, how could a populist political party rooted in Alberta be anything but conservative?

But what is populism really? Trevor Harrison answers the question in his book on right-wing populism and the Reform party: “In short, populism constitutes an attempt to create a mass political movement, mobilized around symbols and traditions congruent with the popular culture, which expresses a group’s sense of threat, arising from presumably powerful ‘outside’ elements and directed at its perceived ‘peoplehood.’... Populist unrest results from the delegitimization crises and the resultant de-composition of previous political alliances. The type of populism that emerges (right- or left- wing) is a product of social, political, and ideological elements set adrift by this process and the consequent reconfiguration of alliances designed to resolve the crisis.”

The crisis that gave rise to Reform began with a long string of western Canadian grievances, which were inflamed when the supposed saviour, the Progressive Conservative party, failed to meet hopes and expectations.

Leading Reform strategist Tom Flanagan, who knows Manning well, agrees that Manning was first and foremost a populist agent of reconciliation and change. “At the deepest level his political career is motivated by a unique personal sense of mission: not, as is often thought, to impose a right-wing fundamentalist agenda on Canadian politics, but to act as a mediator, to bring together the warring factions into which Canadian society has become divided.” Flanagan describes Manning as a “human barometer of political dissatisfaction lying beneath the surface.”

Flanagan’s impression of Manning is consistent with Manning’s view of himself. “I came to the conclusion that if I was ever to be personally involved in politics, I wanted to be involved in a genuine populist movement rather than a traditional political party.

Manning wrote that populism is the “common sense of the common people [that would] allow the public to have more say in the devolvement of public policy through direct consultation, constitutional conventions, constituent assemblies, national referenda and citizens’ initiatives.”

Yet he acknowledged to Flanagan that both populism and conservatism were intrinsic to Reform. He also recognized that populism is inherently short-lived. Flanagan remarked: “Manning has always emphasized that his populist project, by its very nature, must be accomplished quickly... the populist impulse will disintegrate and the party will be left with the conservatism of its members.”

The stark reality is that populist movements are inherently transient. The Reform party’s original constitution includes this remarkably bold and unprecedented clause: “This constitution shall become null and void, and the Party shall cease to exist, on November 1st, 2000 ad, unless this Constitution is re-enacted in its present or amended form by a two-thirds majority of delegates to a Party assembly held before that date.” The Reform party was populist in the way Social Credit was populist when Manning’s father was premier. “Manning thinks in terms of a new party sweeping to power on a tidal wave of popular discontent, as Social Credit did in 1935 in the depths of the Depression.”

There are two popular conceptions about Manning’s political views: that his political philosophy is grounded in his Christian beliefs, and that he is an extreme right-wing conservative. Flanagan counters both. Manning does have deeply held religious beliefs, but

he believes that important moral issues should be decided by referendum and not be based on the moral conscience of a political party, its leader, or an individual member. This suggests that Preston Manning would support initiatives to increase access to abortion, obviously anathema to his Christian beliefs, should it be the majority position of his electors.

There is clear contradiction between being populist and showing attachment to any particular political philosophy. Presumably, those who identified themselves as left or socialist would find comfort with the NDP, while those on the conservative right would align with the Progressive Conservatives. Those living in Quebec who believed in separation and a Quebec nation would align with the Bloc Québécois. In its pure form, populism is more a methodology than a consistent stance on a series of issues. For a populist party to survive and succeed there must be a broad consensus that none of the current political philosophies respond to voter concerns. Some suggest the Bloc Québécois is populist because it was born out of political uprising. It is anything but, because it has a well-defined agenda with coherent and consistent policies designed to deliver the destiny it sees for Quebec.

For Reform to work as a populist party it could not be a purely conservative or right-wing party. Manning knew this, which is why he never wanted the right-wing label. He knew that unless he could attract voters away from mainstream political parties right across the country in somewhat equal proportions, his project would fail.

So, was Preston Manning as conservative as his Reform party members? Flanagan doubts this, for a number of reasons. He saw that Manning was fundamentally opposed to deficits and the burden of debt, but that view could easily be held from the left; witness Tommy Douglas, the former socialist NDP premier of Saskatchewan. Manning did not support an end to interventionist supply-management marketing boards and would also continue farm income subsidies. He supported social programs and opposed privatization of pension plans. Manning, said Flanagan, “is eclectic in his thinking, and has a tendency to embrace contradictory positions in a belief that they will be reconciled in some future synthesis. He is certainly not a socialist or even a liberal, but in ideological terms he could lead a centrist party with a favourable orientation to business …He envisions a dynamic process in which he will recruit centrist or even leftist members, whose presence will change the party’s ideological center of gravity, which in turn will make it more hospitable for centrist, leftists and so on. Eventually, he wants Reform to embrace the whole ideological spectrum, just as he wants to become a demographic microcosm of the whole Canadian society.”

To some in Canada, populism has a negative connotation. It is seen as a place where disaffected and angry misfits attempt to congregate legitimately because they cannot find a home in any of the mainstream parties. Manning tried his best to avoid this stigma, although he did acknowledge the inherent risk of his undertaking. “There is some academic literature where populism is a perversion of democracy where some demagogue bamboozles the public into support. I acknowledge there is a dark side to that. But that was never what we were talking about. It is a phenomenon that has its dark side but it is a very admirable phenomenon when it works properly.” It doesn’t always work properly. Brian Mulroney is reported to have warned Manning about the dangers of cobbling together a coalition of the disaffected: “You can build an army of opportunists, but you can never make them march.”

Manning was uncomfortable calling himself a populist or a conservative. “I stopped using populism because of the perceived negatives and just kept using democracy, democratic grass roots, bottom up, those types of words.” This labelling confusion irritated Manning. “The people that argue that Reform was populist, and to them populism is a derogatory word, they are often people who don’t really like democracy but don’t have the guts to say it, so they call it populism in protest.” For Manning, Reform fit into a broad historical and sociological context. “There are two parts of the country that innovate politically in the sense of supporting new movements outside the traditional ones... there are two parts of the country that are systemic changers. One is Quebec with that long list of third parties: Bloc Populaire; Union Nationale; Ralliament des Créditistes; BQ; ADQ. The other of course is the West with its stream: Riel, the independence movement, the Progressives; the depression parties, CCF, Social Credit, and then Reform.” Manning believed the urge to be different is somehow innate. “I argue there is something in the juices of these two regions that produce these movements, and will produce these movements sooner or later no matter what.” (Brian Mulroney responded to the notion of western juices by saying one could hardly expect westerners to remain calm when a political leader is telling them on a daily basis that they are being abused and exploited. It was one thing, argued Mulroney, to foment discord. It was quite another to govern the country where a national and inclusive perspective is required.)

The Reform Party of Canada was not established with a neutral ideological bent. The populist methodology was encumbered in the first instance by a number of predetermined views enshrined in its Statement of Principles. These included: a Triple-E Senate (elected, effective, and equal); conserving the physical environment; protecting the family unit; a free-enterprise economy; collective responsibility for the care of basic human needs; balanced budgets; and positive relations with the United States. These were the principles Manning hastily wrote on a sheet of paper that became the Reform party constitution. A truly populist party would not have policy markers in its constitution; rather, it would have various mechanisms and procedures to prioritize the will of electors and citizens.

Tom Flanagan questioned the legitimacy of populism in the Reform party: “The populist dream of consensus about policy matters is both empirically impossible and logically incoherent... as a political leader Manning operates with an intuitive grasp of the importance of agenda control, and within the Reform Party he tries to reserve that control for himself.”

Manning’s commitment to democracy also appears to have its limitations. Even within the party’s hierarchy, Tom Flanagan reported that Manning exercised de facto control over the nomination of the chairman and officers of the party’s executive council and the chairmen and members of all committees “... to ensure that all key positions are filled by reliable loyalists and to isolate mavericks on the council.” And when Reform party pol- icy was adopted at general assemblies and conventions, Manning frequently ignored those aspects with which he was not completely comfortable. “The relative lack of concerns with assembly proceedings and decisions stems from Manning’s feelings that he is not bound by them.”

Ted Byfield, a Reform party founder and creator of the Alberta Report, did not believe Manning was a populist and suggested he was more interested in control and power: “It always seems to me that [Manning] is always advocating something [populism] that is incompatible with his own instincts.... And I think that will likely get him into trouble before he’s finished, too, because it isn’t his [first] instinct. [Preston] is the authoritarian of the first order, [just] as his father was…”

The arguments that ultimately led to the merger between the Progressive Conservative and the Reform-Alliance parties were as valid throughout the 1990s as they were in 2003 when the merger was consummated. The parties were eating each other’s lunch.

Preston Manning was never comfortable with Reform being placed on the right wing, as in pro–free enterprise and minimal government, or the left wing, as in redistribution of wealth and state-run social programs. He thought that Conservatives on the right had “hard heads and hard hearts,” while the New Democrats on the left had “soft heads and soft hearts.” His political goal was to be “hard headed and soft hearted.” Yet in his autobiographies, Manning provided no evidence that Conservatives were hard-hearted. Instead, he pointed out that 60 per cent of government spending while Mulroney was in office was on social programs, hardly the measure of a hard-hearted politician. In elections to come, Reform party platforms would cut heavily in these areas.

Manning was alone in arguing that Reform was not on the right of the political spectrum. Trevor Harrison said: “The data support the widespread contention that Reformers are, in general, disgruntled Tories or previous supporters of other right-wing parties. The party’s 1989 delegate survey found that 78 per cent of the delegates identified themselves as previous Tories, 5 per cent Socreds, 5 per cent Liberals, and just over 1 per cent Confederation of Regions members. Similarly, the 1992 delegate survey found that over 79 per cent had voted Tory in 1984, while 46 per cent did so again in 1988, compared with 36 per cent who shifted to Reform.”

Reform members were far to the right of the Progressive Conservative party. Yet Manning didn’t even want to say he was a conservative. “Stephen Harper and I were conservative and could see the obvious contradiction,” said John Weissenberger. So could the media. They viewed Reform as ultraconservative. Denying reality made Canadians suspicious of Reform. “The critics would say you are not calling yourself conservative, but you have nothing but conservative policies,” said Weissenberger. “It seemed to Stephen and myself that this was an untenable position. That left us open to the accusation that we had a hidden agenda.”

It is hard to imagine a more ideologically driven party or leader than Preston Manning and Reform. The party’s 1989 convention survey found that on a 7-point scale defining left–right ideology (left =1, right =7), Reformers placed themselves at 5.08; the Canadian electorate at 3.74; the federal Conservatives at 3.5, the Liberals at 2.63, and the NDP at 1.85.

While Reform party members viewed themselves far to the right of the PC party, most western conservatives saw Reform as more innovative than extreme. John Weissenberger thought an average member of the PC party was not much different from an average member of the Reform party. What was different was the apparatus and the leader- ship. Reform party members could see their conservatism represented in the Reform party. What they saw in the PC party was decision making and leadership dominated by centrist Red Tories. Reform party members by and large represented a view of Canada that was strongly anti-government, anti–social welfare, and anti-Quebec (as in opposed to official bilingualism in the federal government, distinct society status, or vetoes for Quebec in the constitution).

Manning did not agree with Harper, Flanagan, Weissenberger, and others who said his populism lacked a philosophical ideology to sustain his political beliefs. In 2006, he looked back at the Reform movement:

I always felt there was an ideological commitment [to Reform]... [beginning with] a principled commitment to small-c conservative economics. We had people who were social conservatives, in the current meaning of that phrase, who had principled commitment to those positions. We had Reform-oriented federalists who had a principled conception of federalism and were trying to implement it federally. We had all of those elements that were principled and value-driven. We had an equally strong commitment, at least I did, to democracy. I think of democracy itself as an ideology and so we had a commitment to that.

It was astonishing to hear Manning say in 2006 that small-c conservative economics were fundamental to Reform, because almost everything he said before 1997 suggested his was not a party of conservative persuasion.

In 2006, Manning also defended his populist notions, suggesting they were integral to democracy:

I used to argue we were a coalition and the way you make coalitions work is you have to reconcile these other principled positions if they are reconcilable, which I argued they were. And the way you reconcile them is using democratic processes. You get everybody in a room; you have a representative assembly; you let everybody have their say, nobody gets shouted down and told you can’t talk about that here. But at the end of the day we have a vote and that’s the position we have until it’s changed. My commitment to democracy was ideological, partly, but also a process commitment as the way you reconcile these other views, which are not incompatible, but still need some reconciling.

Manning felt he was leading a party where democratic mechanisms were used to establish policy within a philosophical orientation towards conservative economic and social issues, such as family values. Also intrinsic to his views was a position of federalism that was fundamentally egalitarian.

Other senior Reform activists for example, Harper and Flanagan, were uncomfortable that party members could choose policies and positions that were inconsistent with conservative philosophy. Manning, however, was entirely comfortable with that outcome. “I think the people who objected to populism, and would have described themselves as ideological, were mainly hard-line fiscal conservatives. That was the kind of party they wanted to create. I agued there was certainly a place for that and we were committed to that. We were the guys who crusaded on budget balancing when the pollsters said you couldn’t get votes that way. But there were other dimensions to our ideology: the social ones, the constitutional ones, and democracy itself.”

Generally, Reform and Manning would have anything but a warm welcome from federalists in Quebec. Manning rejected the notion that Canada is a product of two founding peoples—English and French—arguing instead for a single nation of equal provinces. He offered Quebec equal status with other provinces. In Manning’s words, “Reformers believe that going down the special status road [for Quebec] has led to the creation of two full-blown separatist movements in Quebec . . . and this road leads to an unbalanced federation of racial and ethnic groups distinguished by constitutional wrangling and deadlock, regional imbalance, and a fixation with unworkable linguistic and cultural policies, to the neglect of weightier matters such as the environment, economy, and international competitiveness.”

On a practical level, Manning’s view gave little regard to how Quebec might embrace Canada. As far as Manning was concerned, if Quebec was not prepared to accept equality with other provinces, then another arrangement should be negotiated:

Either all Canadians, including the people of Quebec, make a clear commitment to Canada as one nation, or Quebec and the rest of Canada should explore whether there exists a better and more separate relationship between the two .... If, however, we continue to make unacceptable constitutional, economic and linguistic concessions to Quebec at the expense of the rest of Canada, it is those concessions themselves which will tear the country apart and poison French–English relations beyond remedy. If the house cannot be reunited [on the basis of equality] then Quebec and the rest of Canada should openly examine the feasibility of establishing a better but more separate relationship between them, on equitable and mutually acceptable terms.

One could easily imagine a very short and largely agreeable debate in which Manning would be pitted against former separatist leader Lucien Bouchard or Jacques Parizeau. Based on questions asked and answered, all parties might come to one conclusion: Quebec must leave Canada. At least Manning was prepared to call their bluff, if bluff it was.

Preston Manning opposed the 1987 Meech Lake Constitutional Accord for a number of reasons, the most important of which was the difficulty it would pose for the establishment of a Triple-E Senate. Manning thought it unlikely that Quebec would agree to accept a formula that gave equality to every province in a new legitimate Senate, and that gave Quebec only 10 per cent of the representatives. Manning was unimpressed that the Meech Lake Accord required the prime minister and provincial premiers to place Senate reform on the agenda of upcoming conferences.

The statism inherent in allowing Quebec to promote and defend itself as a distinct society with special powers was also of concern to Reform. Manning made no specific argument about the difference acknowledging Quebec as a distinct society would make to the daily lives of western Canadians. What did Albertans care if the courts of the land interpreted the constitution to recognize the inherent obligation of the Quebec government to protect its language and culture? Even without the distinct society clause, Quebec, and other provinces, could impose whatever language laws they wanted under Trudeau’s constitution by simply invoking the notwithstanding clause. Ultimately, Manning and the Reform movement grew tired of having progress on important national issues thwarted because central Canadian elites needed to deal with the Quebec question.

For decades, federal Liberal governments had been intruding into areas of provincial jurisdiction by using federal spending powers. This was a huge frustration to many provinces, including Quebec. Manning wanted to scuttle the federal intrusions and return the responsibility and taxation room to the provinces. It is unfortunate that Manning was never able to articulate his views in French. If Manning had a legitimate ally on respecting the Canadian constitution and the allocation of powers between the federal and provincial governments, it should have been Quebec nationalists such as Lucien Bouchard. Manning recalled: “We always felt that if we could ever have communicated that in Quebec, or found an ally who could have communicated it, there was a very interesting commonality between western Canada and Quebec on that issue. Of course I was crippled there by not being bilingual.”

Manning and Harper were prepared to take their vision of Canada into Quebec. “We called our view a new federalism: not the status-quo federalism of Chrétien and the Liberals; not the kick at the pieces approach of the Bloc; but a reformed federalism. We talked about rebalancing the powers where you respected the provincial governments in their area of jurisdiction. You got the federal government out of these areas, you vacated the tax room that they occupied and gave it to the provinces,” Manning explained. But it was hard for Reform to be heard in Quebec. Reform was seen as the party that led the fight against Meech Lake, the party that would not allow Quebec to be recognized as a distinct society.

To be clear, the Meech Lake Accord was not an influence in the initial meetings that led to the founding of the Reform party. The Meech Lake Accord was signed on June 3, 1987, just after the Vancouver Assembly that led to the launch of the Reform party.

The first electoral test for reform came in 1988, when Brian Mulroney’s government faced the electorate for the first time. Speaking in 2003, Mulroney recalled his puzzlement at the prospect of facing Preston Manning and the Reform party on the ballot, given his government’s record at responding to western grievances:

We had not run a perfect government. We had made mistakes. But, as I arrived in Alberta to begin the campaign I felt reasonably confident, however, of taking on this coalition of Free Trade opponents: unemployment was down; growth was strong; the NEP was abolished; FIRA was eliminated; the wave of privatization had begun; we had negotiated the Canada–U.S. FTA, an initiative ardently sought by Western Canada for generations; we had three Albertans in Cabinet in positions of great influence: Messrs. Mazankowski, Deputy Prime Minister; Clark, Foreign Affairs; Andre, Government Leader. I was running the most conservative government since Prime Minister St. Laurent and our government had responded more fully to western Canadian aspirations than any other in modern history. Imagine my surprise, therefore, to find that, running against us and cutting into our vote at the centre and centre-right, was Preston Manning and the old Social Credit Party, then dressed up under a new name, the Reform party. This was the beginning of the division of conservative forces in Canada. At the very moment the centre-right was gaining effectiveness in Canada, Mr. Manning chose to launch a new party, split the vote and give rise to the political fragmentation we know today.

The election was dominated by debate over the Free Trade Agreement with the United States. Liberal leader John Turner said opposition to the FTA was the “cause of his life.” In the free trade debate, Reform was on the same side as the Tories. Conservative- minded voters feared that placing a protest vote with Reform might defeat the PCs and thwart the trade deal. Those who might otherwise have voted Reform instinctively knew the consequences of splitting the conservative vote. Mulroney would later remark, “Had Westerners truly split the conservative vote in 1988, Canada would never have had free trade, something the West had wanted for the past 125 years. As it was, a number of NDP were elected in 1988 because of vote splitting.”

Don Mazankowski recalled that Reform certainly made its presence felt in 1988, but that the election battle lines were drawn around free trade. “I ran in seven election campaigns. That one was the most satisfying because it was clearly an issue-oriented campaign. One side was going to win and one side was going to lose and Canada was going to take a different track. That is the real genius of the Mulroney government.” If western alienation was real, this was not the election where it was safe to give it expression.

The major issue that Reform brought to the electorate in 1988 was financial mismanagement, specifically the inability of Mulroney’s government to balance the books.

Much of the Reform effort was focused on the riding of Yellowhead, Alberta, where Preston Manning took on Joe Clark, then minister for external affairs and a former Tory leader. It was clever and politically savvy for Manning to pick such a high-profile opponent. No one expected Manning to win, but the contest gave Manning the opportunity to debate and ridicule a former Conservative prime minister in local debates and on local media. Such encounters would be played across the country, giving both Manning and Reform some much-sought-after publicity.

Author Graham Fraser describes a campaign event where Preston Manning squared off against Joe Clark:

Manning... was cheered when he told the audience to send the old parties a message, and that his election would be a warning to MPs across Canada. “If you [Clark] will not faithfully represent those who elect you, you will be replaced by someone who will.” This was the issue people questioned Clark most closely about. They opposed bilingualism and favoured capital punishment: he [Clark] had supported bilingualism and voted against capital punishment. “How can we vote for you if you don’t vote for us?” one member of the audience asked.