Читать книгу Full Circle: Death and Resurrection In Canadian Conservative Politics - Bob Plamondon - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

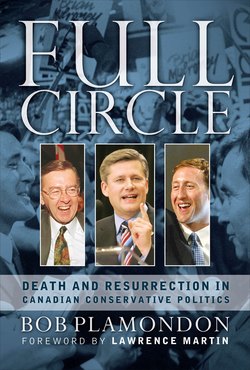

PETER MACK AY

ОглавлениеFirst elected to office at the tender age of thirty-two in 1997, Peter Gordon MacKay belongs to a new generation of technologically savvy politicians. But this fresh-faced and dynamic parliamentarian received his primary education in a one-room schoolhouse with no running water, a wood stove, and a two-seat outhouse.

“I caught the tail end of the one-room schoolhouse,” boasts MacKay of his good fortune. It was an antiquated beginning, but MacKay describes it as idyllic: “It was like being on the set of an old-time movie. It was perfect.” MacKay thinks many of his generation in rural Canada grew up this way, but in 2006 it’s not a story many forty-year-old Canadians can tell.

Peter remembers the ruggedness and simplicity of the school- house. His hats and mitts were littered with scorch marks from the school’s wood stove. All he had to do to be first in his class was beat Beverly York, the only other student in his grade. To this day, Peter can recall the names of every student in the school, and tell you how their lives have evolved.

For the record, Peter MacKay, born on September 27, 1965, on Temperance Street in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, was the second of four children of Elmer and Macha MacKay. Reflecting on his youth, Peter points out that he was lucky enough to have two additional sets of parents. Indeed, MacKay is as likely to tell stories about his grand- parents as he is about his mom and dad.

His maternal grandfather, Bradin Delap, was born and raised in Rye, Ireland. He was a distinguished and decorated man who served in two world wars and retired from the navy as a commander. He then went to work for Western Union and led the team that laid the first transatlantic cable. The first picture transmitted across that cable was of Peter’s grandmother holding his mother. Ultimately, world travels gave way to a more peaceful setting and life as a blueberry farmer in the Annapolis Valley of Nova Scotia. Bradin was a loving, affectionate, and playful man. Whenever the MacKay children would pinch some blueberries from the bushes, Bradin could be heard loudly complaining about “those damn mice,” just so he could enjoy the giggles from the MacKay kids lurking nearby.

Peter’s paternal grandfather, Gordon MacKay, was a machine of a man who often performed legendary feats of toughness and strength. During the depression, when work was scarce and complaints were few, Gordon would impress the locals with his endurance. One memorable day he hauled some heavy equipment between neighbouring farms on his already callused back, the work you would expect of a heavy horse. When he reached the laneway leading to the barn, a crew of three came to take his burden. “Don’t touch it,” Gordon warned. “I’m taking it all the way.” In many ways, he was a twentieth-century version of mythical lumberjack Paul Bunyan. He was a playful man who loved his grandchildren, but he could also be tough. He had a task-oriented and business-minded approach to getting things done, and done right. But he also would help those who were down on their luck. If someone in the community was facing hard times, particularly if they were a visible minority, he would go to the town office and pay their taxes. He owned the local lumber mill and would often send construction materials to hard-working farmers who couldn’t make ends meet. He hired dozens of new immigrants to Canada, mostly Estonians, to work in the woods, paying them in advance. When he was practicing law, Peter would emulate his grandfather by doing pro bono work. On one occasion an elderly black man whom Peter had helped with a charge for petty theft thanked him by saying, “I know who you are. You are the grandson of Gordon MacKay.”

A daily presence in Peter’s life from the start, Gordon MacKay taught Peter how to fish, ride a bike, and change a flat tire. Gordon was also his taskmaster. “He was affectionate and fun; but he was also all about hard work.” If Peter got the sense that life was no dress rehearsal, it was from the lessons imparted by his grandfather. What seems surprising is that through his youth, the often-impatient grandson never once tasted the consequences of letting his parents or grandparents down. “The one thing I would never want to hear from my dad or grandfather was that they were disappointed. To this day, that would be the most cutting thing they could say.”

As a young man, Peter had the presence of mind to tape-record his grandfather, to recall the many amusing and heroic stories and to preserve and revere his voice and persona. The mementoes on dis- play in Peter’s office connect him with his grandparents.

Macha Delap, Peter’s mother, met Elmer MacKay at Acadia University. They were married in 1961 and took up residence first in New Glasgow, where Peter was born. They ultimately settled in the old MacKay homestead in Lorne, in Pictou County, Nova Scotia. For the early years of his life, Peter lived in a world contained within a one-mile radius bounded by his grandfather’s lumber mill, the grist- mill, the outbuildings and barns, the one-room schoolhouse, the apple orchard across the street, and, of course, the fishing stream. Elmer MacKay describes his young son as the quintessential Canadian lad. “He was kind, hard-working, conscientious, and never complained. He always wanted to do what was right.” Elmer recalls a telling incident: “When Peter was about twelve years of age his grandfather let him drive his truck in the back woods. Peter was backing up with the door open and caused some damage. Peter felt bad and gave his grandfather the twenty dollars he had and told him he would get more. Peter’s conscience will always guide him to the right thing.” Although his family had means, Peter was not spoiled either with material goods or praise.

Life took a different turn when Peter was six. His dad, a popular and respected community lawyer, was recruited to be the Progressive Conservative candidate in a federal by-election in Central Nova on May 31, 1971. This was a seat the Liberals were supposed to win. They had finagled the by-election by offering the sitting PC member, Russell MacEwan, a judgeship if he would resign. The Liberals recruited a high-profile broadcaster named Clarrie Mackinnon to carry their banner. It was a tough campaign in a place where everyone knew about hardball politics, the sort of place where the Liberal from the adjacent riding had earned the nickname “god- father.” That’s what they called Liberal heavyweight Allen J. MacEachen, the man who desperately wanted the Liberals to take Central Nova from the Tories. The benefits of having the godfather on your side were noticeable: “You knew right away from the quality of the pavement which riding you were in and who was in government,” said Peter MacKay. But the residents of Central Nova proudly shunned the Liberal government’s goodies and sent Elmer MacKay to Ottawa with a healthy surplus of votes.

The life of a parliamentarian was different in the 1970s: MPs would stay in Ottawa for months at a time, returning home only when the House was not sitting. Elmer’s absences were hard on Peter, and hard on the MacKay marriage; under the stress of politics, it didn’t last two more years.

Macha MacKay took Peter and his siblings to the Delap home- stead in Wolfville. It was only about 250 kilometres from Lorne, but to Peter it felt like the other end of the earth. Being closer to his maternal grandparents was the only thing that redeemed the move. He particularly looked forward to the summers when he would return to Lorne to be with his other grandparents and his father. Lorne was a place to make hay, plant vegetables, fish, and play sports. Peter’s father was one to make sure that play followed work. “He would give me a list of things to do and there would be an accountability session later to see what had been accomplished,” MacKay said. He maintained regular contact with his dad after his parents’ divorce; his grandfather Gordon often drove to Wolfville to pick up the MacKay children for the regular trek to Lorne. Peter’s heart remained in Lorne. It still does.

Peter’s mother was a left-leaning social activist. She rebuilt her post-marriage life by earning a master’s degree in psychology and pursued her passion for international justice and issues of women’s health. With the help of her parents, who often stepped in to care for the four MacKay children, Macha was able to travel and then share her experiences from the Third World with her children. She would often bring home visiting University of Acadia students for supper; the students came from countries of which most people had never heard. The education Peter received by being exposed to his mother’s world was every bit as valuable to his outlook on life as were his more formal studies. As a woman of social conscience, Macha was not blind to the harm done by well-intentioned governments that claimed to be helping the less fortunate. Peter had a sense she was more comfortable with non-governmental organizations than she would have been working for a government agency.

Macha never remarried. Elmer MacKay, on the other hand, married twice more and had another daughter, Rebecca, whom Peter considers as full a sibling as Cethlyn, Mary, and Andrew.

Peter was always involved in sports, with a passion for hockey, football, baseball, and rugby. Not known for raw talent and finesse, he was skilful as a mucker and grinder, someone who would tough it out in the corners, fighting for an edge against any opponent who came his way. Peter’s rough-and-tough sportsman side is offset by a not-so-well-known aptitude for art and drawing, a passion he studied at university and something to which he might well return if the day ever comes when he doesn’t feel the need to be so engrossed in politics.

Despite a father in cabinet and a community-minded activist mother, Peter was adamant in his youth that he was not going to be a politician. He knew from experience that achieving the life–work– family balance could be next to impossible. Even today, it seems this struggle persists. “I really don’t want to miss having a family. It weighs heavily on my mind,” said MacKay. The divorce and the love from his grandparents explain why MP Peter MacKay introduced Private Member’s Bill C-309 to amend the Divorce Act. Had it not died on the order table, the bill would have given interested grand- parents automatic legal standing in divorce cases, entrenching an undeniable interest.

Peter was a steady student who accomplished the trilogy of a strong B average, an active social life, and a daily dose of sports. His passion for competitive team sports eclipsed any interest in politics that one might expect in the kid of a politician. Beyond talking poli- tics around the dinner table or on the long drives between his parents’ homes, Peter showed little interest in partisan activity. He shunned any form of student politics. His first meaningful exposure came when he was seventeen, in the 1983 by-election in Central Nova. Peter’s father, Elmer, resigned the seat so Brian Mulroney, newly elected leader of the PC party, could enter the House of Commons. Peter worked as driver for Mila Mulroney and her assis- tant, Bonnie Brownlee. He enjoyed the glamour of driving powerful and beautiful people past the local ball fields where his friends were playing, but what he remembers most about the by-election was when hockey legend Bobby Orr came to the riding to help Mulroney. Such was Peter’s early superficial involvement in politics.

Peter went to Carleton University for his first year of under- graduate studies and to play varsity football. He thought moving to Ottawa would allow him to spend more time with his father. (Elmer had resigned his seat in 1983 in favour of Brian Mulroney, but he ran successfully for the same seat in 1984, when Mulroney ran in Quebec.) But it didn’t turn out that way. Football was also a problem, as he was red-shirted and didn’t play.

After spending a second summer working in the High Arctic on supply boats, Peter returned for second-year studies at Carleton and another round of football tryouts. Within a few weeks, Peter was told that his grandfather MacKay was dying. A gnawing feeling that he was not where he was supposed to be overcame him, so he packed his bags and returned to Wolfville. Returning home to Nova Scotia in a time of personal crisis and stress would become a pattern repeated many times in Peter’s life. Peter finished his undergraduate degree at Acadia and graduated in 1987 with a bachelor of arts, majoring in history and politics.

“I always wanted to be a trial lawyer,” MacKay had declared in his high school yearbook. It was a good choice for a competitive rugby player. However, he thought he would always be a defender, not a prosecutor: “That was probably my mother’s altruistic influence; that it was a noble thing to do.” He studied law at Dalhousie University and was called to the bar in 1991. It was not long, however, before MacKay fell into his father’s footsteps and set up a private practice in New Glasgow. His law office was above the local pizzeria, not more than a few blocks from where his father had set up his practice. “I had some clients who were the sons of the people my father defended: for him it was bootlegging, in my generation it was drugs.” He gained some international experience early in his legal career on a six- month contract in Kassel, Germany, where he gave legal and strategic advice to Thyssen Henschel, a large defence contractor.

Returning to Canada, MacKay took per diem legal work for the Crown prosecutor’s office. The office was short-staffed because of an inquiry into the Westray coal mine disaster, and within months Peter was brought on full time. “It seems throughout my entire life, I don’t wade into things. For some reason or another, I always get thrown into the deep end. But it can be a great way to learn,” MacKay said.

Working as a Crown prosecutor exposed Peter to a host of public and community interests. He worked with the police, victim advocacy groups, government agencies, and with people in deep crisis and conflict. “It showed me a much bigger world than I had worked in before.” He learned to be discreet and to use careful judgment. The failings of the criminal justice system confirmed MacKay’s politics. His mother’s commitment to social and environmental jus- tice had left its mark on his thinking, but MacKay came to the conclusion in his mid-twenties that his overall thinking was fundamentally conservative. MacKay believes in being tough on crime, and in particular on young offenders. He is tight-fisted, or as his friends say, “He has nickels in his pockets as heavy as manhole covers.” His frugality applies to taxpayers’ money as well as to his own, which is just the way his constituents want him to be. He also carries the work ethic, community mindedness, and entrepreneurial interests of his grandfather. Put it all together and you have what MacKay calls a “practical conservative.” His mother is a frequent and meaningful sounding board for him, although she might disagree with her son’s vocation.

As a Crown prosecutor, MacKay handled everything from shoplifting to first-degree murder cases. Although it may not have been apparent at the time, being in court and making arguments daily turned out to be good training for the House of Commons. He even made it to the Supreme Court of Canada, arguing a precedent- setting case concerning the police seizure of video gambling equipment where no warrant had been obtained. As he is inclined to do, MacKay describes the setting with a metaphor to sports: “If I had been a ball player, it would be like playing in Yankee Stadium.”

Peter felt he had found his niche. He loved the job and the people he worked with. But he was summarily fired as a Crown prosecutor on March 4, 1997, because of a perceived conflict between being a non-political public servant and being a candidate for political office.

They are all conservative politicians, but they are substantially different men. MacKay is the most sensitive, Harper the more temperamental, and Manning the most detached. When it comes to religion, Manning is in a league of his own. In their spare time MacKay talks sports, Harper conservative economic theory, and Manning Canadian history. If you were out for an enjoyable and fun dinner with the three of them, you would want MacKay to do most of the talking.

Manning and Harper would be more likely to sign up for a debate, especially if the subject is dry and requires a painstaking amount of research. MacKay is the Boy Scout of the three, a dutiful soul who never wants to disappoint. If they were not in politics, Manning would lead a think-tank, Harper would be a tenured and well-published university professor, and MacKay would be commissioner of the National Hockey League.

In the mid-1980s, the paths of Manning, Harper, and MacKay had yet to converge. Brian Mulroney was about to make his mark on the nation.