Читать книгу The Gang of Four - Bob Santos - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe press called him “Sockin’ Sammy Santos.” Sammy’s success in the ring was a source of pride for the local Filipino American community. During the late 1920’s, boxer Sammy Santos fought as a lightweight in California, Oregon, and Ohio, then ended up in Seattle, a popular fight town in the old days. He had earned a reputation of toughness, armed with a tremendous punching ability.

Unfortunately, Sammy never made it to the top. He came close, one fight away from a championship bout, but never won the “big one.”

Like Sammy, young single Filipino males had come to America in the 1920’s and 1930’s with dreams of making their fortunes. They became part of an itinerant migrant labor force that worked the Alaska canneries and West Coast farmlands.

Seattle’s Chinatown was a natural stopping off place for those resting between the cannery and the fields. Given the residential segregation laws prevalent in the city, the area was one of the few in the city where Filipinos could live.

One of Sammy’s hangouts in Chinatown was the Rizal Cafe where a young beautiful Filipina waitress named Virginia Nicol caught his eye and his heart.

Sammy and Virginia were married in 1931. In 1932, soon after Sammy retired from the ring, they had a son, Sammy Junior, (he was called Sammy Boy). In 1934, a second son, Robert Nicholas, was born. But everyone would call him Bobby.

Tragically, soon after Bobby was born, his mother Virginia was diagnosed with tuberculosis. She deteriorated rather quickly and died at the young age of 23 in 1935. Little Bobby never got to know his mother. His only memories of her were from pictures Sammy had kept.

Sammy Santos, the young widower, found it very difficult to raise two young energetic boys, so he reached out to the in-laws for help. The oldest, Sammy Boy, went to live with relatives in Tacoma. The youngest, Bobby, went to live with his Aunt Toni (Virginia’s sister) and Uncle Joe Adriatico in an apartment on Spruce Street, in the Central Area. They had two children of their own, Adela and Joe Paul, as well as Patrick, an adopted cousin. Little Bobby was warmly welcomed as one of the family.

Uncle Joe came from a well-connected political family in the Philippines. Joe’s father, Macario, was a political foe of Manuel Quezon, the first president of the Republic of the Philippines. Joe was a well-read, politically savvy man with common sense views. It was he, more than anyone else, who first shaped Bobby’s early political awareness.

Aunt Toni was a very generous woman and a devout Catholic. She volunteered her time to help the poor and she took in and provided for foster children. At the age of six, Bobby started parochial school, attending the Maryknoll School for kindergarten.

Seattle’s Chinatown was an exciting world for young Bobby Santos. It was a cosmopolitan area where not only the Filipinos called home but was also home to the Chinese and Japanese immigrants. When Bobby was old enough, he stayed with his father on the weekends and holidays in Chinatown. Bobby looked up to his father. He memorized each page of his father’s worn out boxing scrapbook and knew every boxer Sammy had knocked out and what round.

3

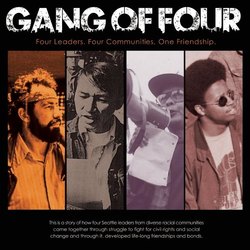

Bobby and brother Sam in 1935. Photo courtesy Santos collection