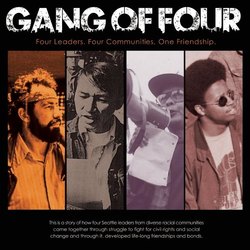

Читать книгу The Gang of Four - Bob Santos - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2: “I Am Filipino” and Filipino Bunkhouses

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, had a direct effect on Bobby Santos. Young Bobby was in the middle of the first grade at the Maryknoll School, a Catholic missionary church and school. Japanese American kids made up the majority of students at the school, with the rest from Filipino families who lived in the neighborhood.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, anti-Japanese hysteria forced the evacuation of all Japanese, citizen and alien alike, from the West Coast. The Japanese community was devastated -- their possessions, homes and businesses were sold for a fraction of their worth. They could only keep the possessions they were able to carry into the internment camps.

Bobby witnessed his Japanese American friends and their families leave the neighborhood, put on buses which would take them to “relocation centers” for the duration of the war. The Maryknoll School was closed. Bob understood that America was at war with Japan. But America was also at war with Germany and Italy. And yet, Bobby wondered then, why weren’t the German and Italian families forced to evacuate as well?

After the Maryknoll School closed, Bobby entered the second grade at the Immaculate Conception School in the fall of 1942. Even though all of the Japanese American families had been evacuated and removed from the neighborhood, strong feelings of anti-Japanese sentiment remained.

At the age of eight, young Bobby had his first real personal experience with racism and prejudice.

During one lunch period, a boy grabbed Bobby and yelled, “Are you a Jap, huh, are you a Jap?” Crying, Bobby answered, “No, honest, I’m a Filipino.” These kinds of incidents were common and not too long after, Asian American kids in Bobby’s neighborhood wore badges printed “I AM FILIPINO” or “I AM CHINESE.”

Most Saturday nights, Bobby and his friends could be found at Filipino community dances held at the Washington Hall at 14th Avenue South and Fir Street or at Finnish Hall on Washington Street. The dances brought out all the single Filipino guys who always outnumbered the Filipino women and girls. Bobby and his friends always knew the latest and popular dance styles--the jitterbug, swing, and the offbeat.

As a teen, Bobby worked at waiting tables at the Navy Officers’ Club, washing dishes at the G.O. Guy Drugs, or cleaning clam nectar pots at the original Ivar’s Acres of Clams restaurant on the waterfront.

Getting a ticket to the canneries in Alaska was a valuable commodity, an opportunity to make a lot of money in a short period of time. Cannery workers were guaranteed $1,200 plus overtime for the season. As a seventeen year old, Bobby had no seniority. But he was the son of Sammy Santos, which carried some weight and favor with Gene Navarro, the union dispatcher. Bobby went to the canneries as Gene’s protégé.

Bobby spent two summers in the canneries. He was assigned to place tops on the cans of fish, then load the cans into boxes for shipment, eight hours a day, during the six-week season from the beginning of June to mid-August. It was hard work.

In the second summer, he was assigned the job of “slimer.” A “slimer” was a job that nobody wanted. As the fish went down the conveyor belts, butchers lopped off the heads and split the fish lengthwise. Slimers stood at workstations with faucets, cleaned out the guts, and placed the cut fish into cans. Slimers worked until the fishing boats were empty.

Bobby got another first-hand experience with racism. The white workers--fishermen and mechanics--lived in a series of single house duplexes while the Filipino workers were crammed into bunkhouses, eight to a room. The whites enjoyed a menu of steak, pork chops, BLTs, waffles, eggs, bacon, and turkey while the Filipinos were fed fish and rice daily, with chicken only on Sundays.

Bobby was not to realize until later how these experiences shaped his political consciousness.

5

A “slimer” was a job that nobody wanted.