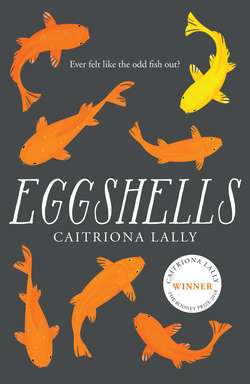

Читать книгу Eggshells - Caitriona Lally, Caitriona Lally - Страница 10

4

ОглавлениеI LOOK OUT the kitchen window at the giant pear tree in the back garden. I don’t like pears, so when the fruit falls in autumn it rots, and the garden is full of wasps and squelches. Now that the tree is bare, it’s as if pears don’t exist and autumn never happens. I open the back door and go outside to look at the treetop. I once read a children’s book about the magical lands at the top of a tree in an enchanted wood. I swing one leg onto a low branch and hoist my other leg up. I climb up a few branches, but there are no signs of elves or fairies or the little man wearing saucepans who appeared in that book. In Bernie’s garden I can see gnomes and ceramic swans, and a small concrete boy who used to piss into a concrete basin. Mary’s back door suddenly opens. I try to hide, but the branches are wintry-bare.

“Jaysus, Vivian, what are you doing up there? Are you stuck?”

“No, I’m fine, thanks. Lovely day, isn’t it?”

These are the wrong weather words, no sooner are they out of my mouth than I feel the damp chill of the air.

“Ah, Vivian, would you look at yourself, a grown woman up a tree on a day like today.”

Even if it wasn’t a day like today—if it was a day like yesterday or tomorrow—I don’t think she would have liked to see me up a tree.

“I’m looking for the lands at the top,” I say.

“The what?” She says “what” like it hurts her teeth.

“In the book The Magic Faraway Tree, the Land of Spells and the Land of Dreams and the Land of Topsy-Turvy appeared on the treetop. I’m trying to find those lands, you see.”

Mary doesn’t see, and she doesn’t really hear either. From this angle she looks neckless, like an up-tilted face mashed onto a body. Her mouth hangs open, and while she’s stuck in the gap between questions I climb back down and escape into the house. I look around the living room to decide which chair I will sit in today. The one with the plastic cover is quite scratchy so I say “No” to that one. I don’t want to hurt its feelings so I stroke its plastic back six times. I have to comfort the chairs in strokes of three, but three itself is uneven and unsatisfactory so I double it and stroke in sixes. Some of the chairs give off a homely smell, of boiled cabbage and unwashed great-aunt. I choose the dark green armchair. It’s ripped and the stuffing peeks through and there’s a great-aunt-sized dent in it, but it’s comfortable. Today I will search for jobs, but first I need to conjure up some company in the room. I turn on the television with the sound down. If I squint and stare at the laptop, the people on the television look like small live people on the other side of the room, a silent gathering which I am sitting apart from. The soap operas are best because the characters spend lots of time in kitchens and on living room sofas, but they argue a lot and even though the sound is down, it causes tension in my living room.

I open the laptop. If I’m in a serious mood, I type “Assistant” into the search box of the job website. I have no particular skills or experience, so I can’t be in charge of anything or anybody, but maybe I can assist with something. Today, however, I am looking for dream jobs. I type “Bubble-blower” into the search box. The computer doesn’t even pretend to search, which is a bit rude. A blank screen appears almost instantly saying:

“The search for ‘Bubble-blower’ in Dublin did not match any jobs.”

The bold type is mocking me, and the language is harsh. It advises me to “Sign up for email updates on the latest Bubble-blower jobs in Dublin.” I try “Walker” next because I’m good at walking, and two jobs appear: a vacancy for a “Dog Walker” in Lucan (I have enough bother controlling my own limbs when I walk, never mind an additional four) and a “Commercial Analyst and Management Accountant” for Walkers Crisps. I’d best not apply for jobs whose titles I can’t understand. Next, I type “Changeling” into the search box. A vacancy for “Graphic Design Print Manager” comes up. It’s suitable for someone who wants “Changeling Roles,” so I scour the print for a description of me. The applicant must have a: “Personality for Sales and Upselling to Clients. Great Personality with Energy. Excellent Communication and Interpersonal Skills.”

None of those things sounds like me. It must be a different kind of changeling they are looking for. I close the lid of the laptop; I never switch it off because that seems so final, like writing a will.

It’s between mealtimes, so I will cook a fry. Somebody has decided that breakfast + lunch = brunch, but I think lunkfast suits this meat-heavy meal better. I melt butter in the pan and cook sausages, rashers and black pudding. The sausages hiss and I’m glad. I like food that sounds like itself. I don’t know when the black pudding is starting to burn because black can’t get any blacker. When the skin of the pudding has hardened, I heap the fry between two slices of white bread. The bread turns soggy with grease—a damp towel of a sandwich—but sog is good in food. I think of other black foods: burnt anything, liquorice, black pepper, half a bullseye boiled sweet. Then I go through other coloured foods in my head until I’m struck with a plan: I will eat only blue foods for the rest of the day. I search the kitchen cupboards but they are bare of blue, so I put on my coat. It’s a heavy coat, packed with wool, and it feels like I’m putting on summer. I put my keys and some money in my bag, but it still seems empty, and I’m not quite sure what else to put in. I’ve seen women carry such big bags—what big lives they must have!—so I take two books from the shelf and put them in my bag. Now I’m someone who could pile six planets on her shoulders and carry them off.

I bang the front door loudly when I leave the house, to rouse the neighbours. I want to tell them about my plan, but no heads pop up from flower beds or peer out from behind doors. I walk to the supermarket, take a basket and move slowly up and down each aisle. I feel like I’ve won a competition where the prize is blue food. I find: blueberries, which are more of a nunnish navy; blue cheese, which smells of socks and tastes of wet dust; blue freeze-pops in mouth-ripping plastic tubes; and a blue sports drink the colour of an ambulance siren. I also pick up several multipacks of Smarties and M&Ms, so that I can sift out only the blues. At the till, a heap of giddy rises up my throat. The shop assistant starts scanning my food.

“Do you notice anything about my items?” I ask.

She looks like she doesn’t want to play my game, so I make it easy for her.

“They’re all blue!”

“Oh yeah, why?”

“I’m having a blue party!”

The snarl on her face melts a little.

“Is it his favourite colour?” she asks.

“Whose favourite colour?”

She looks confused.

“Your little boy, are these not for his birthday party?”

I think for a moment.

“Yes, they are. And I’m making a Smurf cake!”

The woman behind me in the queue pokes her head into the conversation.

“Ah, that’s lovely, what age is he?”

“They’re six, I have boy twins.”

The words glide out of my mouth like a silk thread.

“You must have your hands full with them,” the woman behind me says, but the shop assistant only stares.

“How come you never have them in here with you?”

“Oh …”

I think for a minute.

“They’re in wheelchairs.”

“Ah, God, that’s terrible, terrible!”

“Who minds them?” asks the shop assistant. Her face is squeezed into strange shapes.

“What?”

“When you come in here to do your shopping, who minds them?”

“Oh, they’re fine on their own.”

“You leave them alone?”

Her voice sounds like a cup shattered on a tile.

I look from one angry face to the other.

“They can’t get out of the wheelchairs, they’re fine.”

They look at each other the way that girls in school used to look at each other: an eye-lock that doesn’t include me. Then they look at me with a purity of hate that stiffens me. I pack my blue items into my bag—I wish I’d remembered to bring a blue plastic bag—and pay. The woman behind me is muttering to the woman behind her, and I catch the words “… social services … shouldn’t be let have kids … something wrong with her …” I take my change and hurry off with great big gulps of marbles in my throat. When I reach the house I rush in, close the door and bolt it. If social services come, they might be angrier that I’m not neglecting children I don’t have than if I was neglecting children I did have. I feel sadder than I’ve ever felt before, sad like the end of the world has come and gone without me.

I crawl under the kitchen table with my bag, and crouch among the chair legs. This is the perfect picnic spot with no chance of rain, and it isn’t too uncomfortable if I lean forward. I lay out my blue feast on the black tiles, empty out the M&Ms and Smarties, pick out the blue ones and put the rest away. I start off with the sweet food then I eat some blue cheese—a horror of a food, so I stuff spongy blueberry muffin into my mouth to cancel out the stinking taste. This feels like cheating, because the muffin is mostly beige with only an inky blue stain. It seems right that on the day of my blue feast I’m feeling blue myself. My belly feels bruised inside, as if all the blue foods were having a fist fight among themselves. The underside of the table reminds me of the inside of a coffin lid, so I decide to practise being buried alive. I crawl out from under the table, take the thickest cushions from the sofa and lay them out under the table. I pile them on top of one another until they nearly reach the top, then I squeeze between the cushions and the table and lie down, with my nose tip touching the wood. I lie staring at the table-ceiling, in the muffled peace of the cushions. I don’t know why people talk of the terror of being buried alive—surely the terror is in being alive.

When my mind has settled, I get out and look up world news on the Internet. The news is: “Possibility of war,” “Terror Threats,” “Elections,” “Bomb Blasts,” “Nuclear Threats,” “Global Downturn,” “Anti-Government Protests,” “School Shooting,” “Potential Chemical Weapons Attacks,” “Alleged Murder,” “Suspected Abuse.” My neighbours like to speak of these potentials and possiblys as definitelys and certainlys. Next I look up national news. A politician is calling on another politician to do something. I would like to call on someone to do something, but I don’t know if anyone would listen. A dossier has been compiled about an organisation. I wonder if there’s a dossier about me somewhere. I close the laptop. The news stories are bouncing off each other in my head and words are producing more words and I picture reams of paper hurtling out of printers, filled with unspaced, unparagraphed, unchaptered words. I switch on the radio and turn the dial to the static between stations, but this isn’t enough to fetch me out of a jangle: I must walk. I put on my coat and pick up my bag. I need some gold in my life because blue has not served me well; I will buy a goldfish. I put on my great-aunt’s double-glazed spectacles as a disguise, in case I bump into anyone from the supermarket, and leave the house. I don’t bump into anyone from the supermarket, but I do bump into the garden gate and the kerb, my eyes watery and blind behind the thick glass. I walk through Phibsborough with my arms outstretched in front of me, feeling for obstacles, then I take off the glasses when I turn onto Western Way. This street makes me think of the lifestyle choices of country singers. I head down Dominick Street and swing left onto Parnell Street. A burly man stands at the door of the taxi company smoking.

“Taxi, love?”

“No, goldfish.”

I go into the pet shop and head for the fish tanks. The man behind the counter comes over with a net.

“Looking for a goldfish?”

“Yes,” I say.

“Right so.”

He lifts the lid off the tank and dips in the net.

“Wait!” I say.

“For what?”

“I haven’t decided which one I want yet. I need to see their personalities.”

The man’s top lip curls up.

“You want one with a good sense of humour?”

I laugh to show that I have a good sense of humour, even though I don’t think his joke is very funny. I lean over the tank. The fish are all swimming in the same direction, except for a slightly slower fish drifting at the bottom. He’s more yellow than orange, and some of his scales are missing. I turn to the man.

“I’ll take the yellow one, please.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

The man scoops out my Lemonfish and puts him in a plastic bag of water, then ties the top of the bag in a knot. I buy some goldfish food, pay the man and put the plastic bag in my handbag. Lemonfish will be happier in the dark of my bag than in a moving house with a see-through floor and a knotted roof. I walk back home, putting my great-aunt’s glasses loosely on my nose so that I can see out from over them. Then I let myself into the house, add water to the bowl containing the lemons I bought yesterday and pour in Lemonfish. At first he keeps crashing into lemons, but soon he swims around cautiously and noses the fruit. Maybe he thinks they’re obese, bitter-smelling new friends. I sit at the table and trace the route I just walked onto greaseproof paper: it’s shaped like a fishing rod that has caught another fishing rod.

I DECIDE TO sleep on chairs in the living room tonight. They will be kinder to me than the bed, which creaks and hisses when I can’t sleep. Tea is a comfort but it keeps me awake, so I boil the kettle and make tea in my hot water bottle. The smell of tea and rubber is a good solid combination, like grandmothers and classrooms. I go upstairs and swallow a blue pill from the bathroom cabinet, one for coughs and colds that makes me drowsy. This will be the last of the day’s blue party. I go downstairs and arrange two soft chairs in front of the red chair in the living room. This way, I get to use three chairs and hurt fewer chairs’ feelings. I take up the spongy cushion from the red chair, and put the hot tea bottle on the chair top. Then I lie face down on the chair, pull the cushion over my head and press it down over my ears. The inside of the chair is musty and my nose is tickled by dust-clumps and crumbs, but it smells of something close to home. I count “One-two-three-four-five-six, one-two-three-four-five-six” until I fall asleep, a sleep so delicious that it has the quality of toasted peaches.