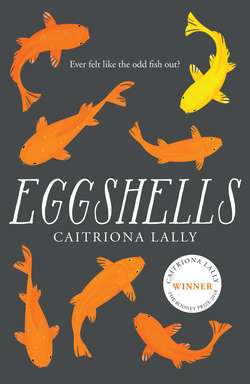

Читать книгу Eggshells - Caitriona Lally, Caitriona Lally - Страница 12

6

ОглавлениеI WAKE ON a damp pillow; my dreams must have leaked. I put my head under the blankets and sniff: it smells aged. I creep out of bed, pull on some clothes from the floor and go downstairs to look at Lemonfish’s bowl. The water is a little cloudy and smells of lemons. I take the lemons out, before he gets too attached to them and knows enough to miss them. He looks at my fingers and the fruit and doesn’t seem to care, but I’m not sure how I’d know if a goldfish cared. I put a pinch of goldfish food in the bowl. I eat a pinch myself—it looks like Brunch ice cream, but it tastes bland and pointless. I eat my mashed cornflakes breakfast and wipe the lemons dry. I’ll bring them to their home in Lemon Street.

I leave the house at a run, calling “Bye” to Lemonfish. The lemons take up most of my bag space. I look busy with life plans. I walk to the bus stop and wait. Two old ladies with tartan shopping trolleys are chatting. A woman is making big exaggerated faces at her child. I wish the bus would come, because the wind is skinning. It’s the kind of vicious easterly wind that makes my eyes water and my nose drip, the kind of cold that makes me hate. I bounce at the bus stop to stay not warm but as not-cold as possible. A man jogs by in shorts and a T-shirt; just watching him makes my eyes cold. When the bus comes we rush the door, and the old ladies use their trolleys as moving barricades to get on first. I sit near the back, beside a man who is on the phone.

“NO!” he shouts. “I had the score and I was outside the off-license an’ it blew out of me hand an’ I went down to pick it up, but some prick got there ahead of me, an’ when I said that’s my money he said he had a knife and if I didn’t fuck off he’d bleedin’ knife me, I’m tellin’ yeh that’s what happened.”

He talks like he’s being chased by words, swallowed up by sentences. Other people in the bus are giving little secret glances over their shoulders at him.

“For fuck’s sake, yeh can go and shite,” he shouts, and hangs up. I root around in my bag to look busy in case he wants to tell me his problems but his phone rings again, a blast of shouty music that makes me jump.

“Hello!” he shouts as if there is a bad connection.

There’s shouting on the other end, and he shouts back: what a feast of shouting.

“I told ya, I was walkin’ to the off-license and some prick held a knife to me throat and said he’d fuckin’ kill me if I didn’t give him a score, that’s what happened, I swear on me daughter’s life.”

The rest of the passengers are silently listening, and I feel proud to have picked the best seat on the bus; some of this man’s fame has trickled onto me.

“Listen, I have to go, me battery’s dyin’, I’ll give yeh a buzz later, alright?”

From the shouting on the other end of the line it isn’t alright, but he hangs up.

“Fuckin’ prick?” he says, and I wonder if I’m supposed to answer. He turns to me.

“Here, you wouldn’t have the lend of a twenty, would yeh? I got mugged, right, by this fucker with a gun, and I owe me friend a score, an’ if he doesn’t get it there’ll be killings.”

“I’ll see what I have,” I say, and I open my bag and pull out two damp lemons.

“You can have these.”

I hold out the lemons. He looks at my hand and then at my face, his mouth hanging open.

“What the fuck am I supposed to do with lemons?”

He says “lemons” like it has two “L”s.

“They’re two for a euro, so if you give him two lemons, you only owe him €19.”

“Are you fuckin’ mental or wha’?”

He puts two syllables into “you”—maybe it’s an honour to get double-syllabled—but he isn’t looking at me in a pleasant way and other passengers have turned around to watch.

“I don’t know,” I say. “All I know is that I have twelve lemons and no money to give you.”

He shakes his head and mutters “fuck’s sake,” but it’s a despairing “fuck’s sake,” not an angry one. He sits silently beside me, shaking his head and giving off alcohol and anger fumes until he gets out at O’Connell Street. As I’m waiting to get off at Nassau Street, the driver looks at me in the mirror.

“He wasn’t bothering you, love, was he?”

“No, he just didn’t think much of my lemons.”

“Ah, I see.”

I get off the bus and cross the street. I walk up Dawson Street and turn into the little arch with shops that sell Celtic jewellery and paintings of horses and chocolates without wrappers. It’s windy in here; there’s a picnic bench in the middle of the plaza, but only a polar bear would enjoy a picnic there today. I walk through to Lemon Street, check that there’s no one behind me, and drop a piece of fruit every couple of steps. When my bag is empty, I look back. The street looks like it has been lemon-bombed. I come out onto Grafton Street, opposite the red-and-white awning of Bewley’s Café. I go inside and sit near the fireplace. It’s cosy here, with red velvet seats and an orange fire and blue stained glass windows. I order black coffee. I prefer milky coffee, but I’ve heard things on the radio about lactose intolerance and I sometimes think that if I stopped drinking milk my life would be a different thing. When I leave the café I take Grafton Street at a saunter, and head east along Stephen’s Green. I make for the Natural History Museum. Students walk by in groups, laughing and in no hurry. It must be a weekday—weekdays churn out people in suits and students with large bags. Weekends have wardrobes full of suits on hangers and school uniforms on floors and children moving about in large doses. I prefer weekdays to weekends; there are fewer people around and expectations are lower.

I walk into the museum. It smells of something old and musty, furniture polish or mothballs. There are glass cases of birds and fish and animals, most of them some shade of beige or brown, with typewritten descriptions on faded, tea-coloured paper. I’m looking for new names of things, a list of new words in a particular order that could form a pattern and give me a clue as to how to find my way back. I take out my notebook and write out the names of interesting-sounding birds: “Chats, Warblers, Wrynecks, Choughs, Buntings, Pipits.”

My list is short: too many names are ordinary and not worth writing down. In the fish section, an enormous goldfish from Mrs. McComas in County Dublin looks healthier than Lemonfish, even though it’s almost a hundred years dead. There are strange specimens in glass coffins and long cylindrical jars, like kitchen jars for foodstuffs. I write the interesting-sounding names: “Natterjack Toad, Butterfish, Butterfly Blenny, Tompot Blenny, Spotted Dragonet, Atlantic Football Fish, Barrelfish, Porcupine Bight, Crystal Goby, Bogue, Poor Cod, Purple Sunstar, Cuckoo Wrasse, Lumpsucker, Boarfish, Comber, Pouting, Beadlet Anemone, Snakelocks Anemone, Dead Men’s Fingers, Sea Pen, Boring Sponge, Smelt, Stone Loach, Shad, Porbeagle Shark, Gudgeon, Darkie Charlie, Leafscale Gulper Shark, Spurdog. Bluntsnout Smooth-Head.” “Bluntsnout Smooth-Head” is like giving an insult and then softening it with a compliment.

Next I head for the cases of butterflies and moths, and pull back the red leather covers. I write nearly all these names in my notebook; they’re like patches of words from a beautiful poem: “Purple Hairstreak, Red Admiral, Heath Fritallary, Painted Lady, Pearl-bordered Fritallary, Small Tortoiseshell, Speckled Wood, Pale Clouded Yellow, Brimstone, Brown Hairstreak, Peacock, Silver-Washed Fritallary, Marsh Fritallary, Ringlet, Bath White, Cinnabar, Grayling, Small Copper, Meadow Brown, Gatekeeper, The Wall.”

The people who name butterflies must be more imaginative than those who name birds—naming a bird Great Finch or Little Owl is like naming a street New Street or Main Street. If I could name things, I’d squeeze chains of consonants together mercilessly without a vowel for breathing room, I’d shove letters together that should never sit side by side in the English language. I’d add numbers and symbols and insist that they be pronounced. I move onto the moths and write: “Ruby Tiger, Puss, Elephant Hawk-Moth, Hummingbird Hawk-Moth, Oleander Hawk-Moth, Bedstraw Hawk-Moth, Eyed Hawk-Moth, Convolvulus Hawk-Moth, Coxcomb Prominent, Sallow Kitten, White Ermine, Pebble Prominent, Buff-Tip, Buff Ermine, Purple-Bordered Gold, Mottled Umber, Scalloped Oak, Early Thorn, Chimney Sweeper, Purple Bar, Magpie Moth, Speckled Yellow, Red Sword-Grass, The Shears, Grey Dagger, The Ear Moth, Burnished Brass, Heart and Dart, Silver Y, Middle-Barred Minor, Flounced Rustic, The Grey Pug, Latticed Heath, Satyr Pug, The Tissue, Plume Moth, The Drinker, Large Emerald, Lunar Hornet Moth, Goat Moth, Vapourer, Red-Necked Footman (which has disappeared and left just a beige stain, probably in a sulk over its name), Northern Eggar, Ghost Moth, Fox Moth, Emperor Moth, Lobster Moth, Figure of Eight Moth, Mouse Moth, Satellite, Garden Carpet Moth, Belled Beauty, Grass Emerald Moth, Straw Belle, Brindled Beauty and The November Moth,” which I imagine is prone to fits of melancholy.

I look through my lists for a pattern or code, but all I find are the names of creatures that include the names of creatures of a different species: “Elephant Hawk-Moth, Mouse Moth, Hummingbird Hawk-Moth, Fox Moth, Lobster Moth, Sallow Kitten Moth, Spider Crab, Goat Moth, Cuckoo Wrasse, Butterfly Blenny, Cuckoo Ray, Nursehound Shark, Sea Horse.”

The moth-namer seems to be overly dependent on his animal- and fish-namer colleagues; he needs to be jolted into originality. I leave the museum and walk down Merrion Street, past the bookshop on Lincoln Place that used to be a chemist and that sells lemon soap regardless of what else it sells. Either James Joyce or Leopold Bloom or Stephen Daedalus (or maybe all three) bought soap there, so it attracts citrus-seeking literary tourists. I walk down Westland Row to Pearse Street—the clock on the tower of the red-brick fire station tells the wrong time—and cross at the garda station. This would be the worst stretch of street for a botched self-immolation; after the firemen quenched the fire, the guards would arrest you for public disorder. I walk by The Steine which, I have read, is also called Ivar the Boneless’ Pillar, after a ninth-century Viking ruler. Two faces are carved into opposite sides of the base of the pillar: those of Ivar, a berserker, and Mary de Hogges. I like that I don’t have to name these faces—I don’t think I could top Mary de Hogges for originality—and I like that Ivar was a berserker; I think I could go berserk myself if certain things happened to me in a certain order without my consent. I catch the number 4 bus heading north. I wonder if the drivers with the fewest accidents and the cleanest buses are rewarded with the single-digit routes, or the routes with a mixture of numbers and letters, or the even-numbered routes, or if it matters at all.