Читать книгу Eggshells - Caitriona Lally, Caitriona Lally - Страница 11

5

ОглавлениеI WAKE TO the sound of me grinding my teeth. I should probably sleep with cotton wool or marshmallow in my mouth to soften the attack. David from the Social Welfare office is visiting today but I don’t want to think about that just yet, so I lie in bed snatching at my dream-thoughts before they vanish through my eyelids: I am in a tunnel that’s split in two, each side rising up to the roof in turn, crushing anything on it. I have to keep jumping from the rising part to the falling part until that too starts to rise. No wonder I feel tired, I saved my own life in my sleep. My throat feels scratched where the scream clogged, I only wake from a nightmare if the scream scrapes through. I wish it were a song and not a scream. Or a laugh. My sister laughs in her sleep. When I used to share her room I would wake in the night to hear her laughing, eyes shut tight, at something that didn’t seem funny in the morning.

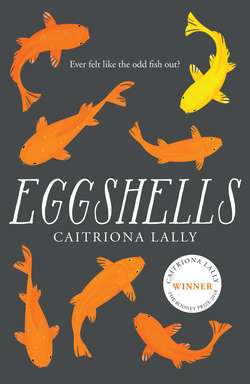

I get up and root through the wardrobe for a pair of khaki combats that will show David I am a serious job hunter. Then I take a dark-green jumper from the shelf. I bring my clothes into the bathroom, put the plug in the bath and run the taps. I duck my head under my pyjama top and breathe in my smell for the last time—even when I leave it another while to wash, the smell will not be this exact combination of sweat and food emissions. I pick up a bottle of pink bubble bath that my great-aunt left behind. The bottle is heart-shaped and ugly, like two inward-facing question marks with no interest in the world. I tip the bottle into the bath. It pours like a thick gluey syrup, turning the bathwater pink and adding white bubbles on top: beer for little girls. Then I hold the bottle over my head and thrust it onto the floor with all my might. The bottle has been transformed into dozens of shards and pieces. I examine them for a while, then step into the bath, squat on my hunkers and lower myself into the water. I stretch out my legs and raise them out of the water, but they haven’t turned into a tail and my skin hasn’t turned into scales and I haven’t turned into a mermaid. I lie back, the bubbles scrinch scrinching, and try to form an expression of extreme calm on my face like the women in television ads, but I’m so hot my heart is rattling in my chest and my toes feel like they belong to somebody else and I can’t relax when I smell like strawberry bubblegum and feel like dirty dishes. I’m not sure how long I have to stay in the bath to be clean, so I swirl the water around and sluice it over my face. Then I lie back with my head facing the ceiling to wash my hair. The water fills my ears and muffles my world; this must be what Lemonfish’s world sounds like. I pull the plug and sit in the bath while it drains. It feels like I should be dying, like my internal organs are being slowly sucked out of my body and down the plughole. I get out, crouch under a towel and tug my clothes on. Then I blast my head with the hairdryer, breathing in the smell of hot burning dust. I eat breakfast and bring Lemonfish’s bowl to the sink. I slowly pour some water out, trying not to lose fish or lemons. Then I turn on the tap and add some fresh water. I’ve just changed Lemonfish’s liquid nappy. I brush my teeth at the kitchen sink and imagine a toothbrush so small that it could brush each tooth individually. If only there was an elf section in the supermarket.

David has the name of a king, so I will clean the house and make it fit for a king-guest. I bring the hoover upstairs and open the door to the hoard-room. A huge toy gun, the kind that stretches across the body and makes a ratatatatatatat noise when you pull the trigger, catches my eye from the childhood-toys pile. It could be useful for a job-hunter so I bring it downstairs. I hoover the landing, then I hoover the stairs, which is like trying to slide down a fireman’s pole in stops and starts, then I hoover the hall and, finally, I bash the hoover in between the chair legs in the living room. I wish I’d made a list of chores so I could put a thick pencil mark through “Hoover House.” Or, to get more pencil strikes, I might divide the chores into:

1. Hoover Landing

2. Hoover Stairs

3. Hoover Hall

4. Hoover Living Room

When the doorbell rings, I’m standing in the hall sniffing my strawberry hands, which smell unfamiliar and hateful. I open the door.

“Hello, David,” I say.

His face doesn’t match his name, David is a gentle name, with soft indecisive “D”s and an open “V,” but this David is pursed and definite.

“Good morning, Vivian,” he says, and shakes my hand—a crisp formality of a handshake.

“Come on through,” I say, because that’s what people in soap operas on television say to visitors, but the words come out in a Manchester accent. He sits at the kitchen table, and Lemonfish swims bowl-side to look out.

“You’re his first visitor, so you must excuse him if he’s shy,” I say.

David half-laughs, a cautious kind of sound without much bark in it.

“Would you like some tea?”

“Please, a drop of milk, two sugars.”

He speaks with an admirable abruptness, but his sentences don’t provide enough information.

“A big drop or a small drop—like a thundershower or a drizzle?”

His face puckers and narrows, as if something under the skin is pulling it back.

“A big drop.”

“Right. Heaped or level?”

“Sorry?”

“Your sugars. Heaped or level teaspoons?”

“Either.”

David waves his hand as if swatting away my question, pulls out a grey folder from his briefcase, lays it on the table and opens it. I fill the kettle and whisper, “Take your time, boil slowly.” I should have added ice to the kettle to slow it down. David clears his throat.

“So you’ve been out of work since when?”

I don’t like being asked questions that are already answered in grey folders.

“Since somewhere between Grand Stretch in the Evening and We Won’t Feel it Now Till Christmas,” I say.

“I’m sorry?”

David is a lot of sorry it seems.

“September.”

“Okay.”

He writes something on a page. David seems like the kind of man who likes neat black words to fit into neat white boxes. I look at his black biro and try to imagine all the other unworkers it has written about. I wonder if he ever writes things like, “Her house smells of boiled mutton” or “His ears stick out strangely.” The roar from the kettle becomes a gurgle and then a click. I pull the lid off the teapot and—oh no!—there is mouldy fur inside. I scoop it out and secretly sniff it—it smells like soil multiplied. When the tea has brewed, I bring the mugs to the table.

“What kind of jobs have you been applying for, Vivian?”

“I’ll show you.”

I go into the living room to get my list. The toy gun is sitting on the red chair like a gift for a king—now is a good time for my trick. I run back into the kitchen pointing the gun at David and holding down the trigger: ratatatatatatatatat! David jumps at the noise; he turns to face me and squeals when he sees the gun pointed at him. Then he scrapes back his chair and dives under the table, his papers scattering around him. I stop to admire the arrangement of white paper on black tiles, it looks like the kitchen has been paper-bombed. David’s face peeks out from under the table—his eyes bulge, he looks like fear has taken him over.

“It’s nice under there, isn’t it?” I say. “That’s where I had my blue feast.”

“Jesus Christ, woman, what the fuck are you playing at?”

I didn’t think officials were allowed to curse.

“I’m playing at Job-hunters, that’s why I’m dressed in khaki. I thought you’d join in the game.”

He gets up from the floor with a creak, his black trouser-knees covered in grey dust and cornflake silt. He sits in the chair, but he doesn’t sit up quite so straight. Then he leans his elbows on the table and puts his head in his hands. When he takes a sup of tea, the mug shakes and spills. I put the gun on the floor and gather up his papers. The top page reads, in squat handwriting:

“Client appears to have inappropriate—”

I put the pages on the table and look away. David is breathing in short gasps that don’t seem to take in much air. I sit opposite him and stare, in silence, until he gives his head a small toss, like a pony or a snooty child, and straightens his papers.

“Right, where were we?” he asks.

“Well, you were on the chair, until I started shooting, so you moved to the floor—”

He waves his hand in the air like a conductor, so I shriek “Lalalalalalala” as loud as I can. He cowers under his papers and hisses,

“Christ, what are you at now?”

“You were conducting, it’d be rude not to make some kind of music in return.”

I like singing—the breath and effort of it—even though I can’t tell from my own ears if I’m in tune. I was told to whisper in my school choir, but maybe I’ve grown in tune since then. I start singing “Doe a Deer,” but I sing quietly so that I don’t scare David. He looks at me like I have bled the last drop of milk from the carton and left none for him, so I drop my tune.

“What kinds of jobs have you been applying for?”

I push my list across the table. He reads aloud:

“Dog walker, bubble-blower, changeling, assistant.”

He turns the page over but that’s all there is. He looks at the list again and seems to wilt.

“Assistant what?”

He has barely enough up-breath to form a question mark.

“Assistant anything, I won’t know until I see the job description.”

“I see.”

His tongue doesn’t quite reach the roof of his mouth, so it sounds more like “I hee.” He picks up the list with his fingertips as if it’s a paper disease, takes a sip of tea and coughs.

“Excuse me.”

“That’s okay, I put half a cough and a quarter of a hiccup in the teapot.”

David closes his eyes and, I think if he had glue, he would have stuck his lids shut. When he opens them again, his eyes seem to have sunk further back into their sockets, as if he’s showcasing his corpse look.

“Have you ever pretended to be dead?” I ask.

His face doesn’t move and his voice, when it comes, is sealed good and tight.

“Have you considered other areas—administration jobs, for instance?”

I prefer an example to an instance, but David won’t understand this.

“I don’t like telephones, and there are lots of them in offices.”

His face twists into a tormented expression, the kind of expression I’ve seen on the faces of war victims on news reports.

“Indeed” is all he says, but he says it like it’s the last word before the end of the world. He rustles through his papers as if he’s looking for an official response, then he straightens up and makes a small speech about benefits and credits and signing on and job seeking and computer courses and upskilling and qualifications in pharmaceuticals or marketing or industries where they are hiring. I nod my head and say “hmm yes” and “oh I hadn’t thought of that,” but I know this is all a cod. Employers won’t hire me to work in their offices when they can hire a shiny woman who speaks in exclamation marks.

“It’s important to keep an open mind,” he says.

“I am open-minded,” I say. “Sometimes I wear my slippers on the opposite feet to change my worldview, even though it makes me hobble.”

David takes a deep breath. He looks like a faded mural in a children’s ward.

“Right, I think we’re all done here,” he says on a new gust of breath, and he bundles his papers and stuffs them into his briefcase. He says half a goodbye and leaves in a great hurry, such a great hurry that it makes me think there’s a fire, so I follow him outside and look up at the house. There are no flames, but the house seems more menacing now that David’s been in it. The smell will be all wrong: the smell of fake strawberry and David and fresh paper. I regret my bath—David didn’t even ask to smell me. I tuck my nose into my jumper and sniff. I still smell strawberry-sweet, but there is also the start of a sweaty tang. I go back inside and walk through the house, closing every blind and every curtain and every door. I crouch in the bathroom, pick up a piece of the smashed bottle and stare into it. I will check every shard, surely in one of them there’ll be a glimpse of where I’m supposed to be.