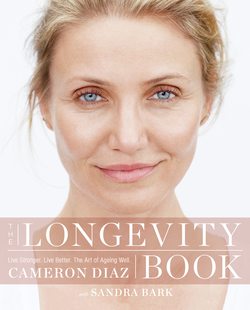

Читать книгу The Longevity Book: Live stronger. Live better. The art of ageing well. - Cameron Diaz, Cameron Diaz - Страница 13

Оглавление

FACT: WOMEN LIVE LONGER than men. A baby girl born in the United States in 2010 had a life expectancy of eighty-one; for the baby boy next door, that number was seventy-six. That’s a five-year gap, enough to make a person really curious about why this might be the case, especially when you consider that this is true around the world, too. Country by country, life expectancies vary (due in part to variables like availability of clean water, access to healthcare, and stability of the region), but the world over, the women’s life expectancies are always greater than men’s.

In the United States, over the course of all that longevity, women use more healthcare services and take more prescription drugs than men do. Researchers at the Mayo Clinic made headlines a few years back when they announced that nearly 70 per cent of Americans take at least one prescription drug daily. They also reported that, as a whole, women and older adults receive the most drug prescriptions. As people get older, they are prescribed more pills to take, not fewer, and the quality and accuracy of those medications has a direct impact on health. The more medicines lined up in your bathroom cabinet, the more important it becomes that you are taking the right medications, in the right doses, at the right times.

Health and healthcare are inextricably bound together. Every time you go to the GP surgery, every time you pop a pill, you are relying not only on your doctor and your pharmacist, but also on medical schools, on drug companies, on research labs, on individual scientists – and their assumptions about women, and their awareness of the latest research about women’s health and women’s bodies.

A lot of people hate going to the doctor, and I get it. Hanging out in a waiting room on your lunch hour or having blood drawn when you’re running late for another appointment is not exactly fun. But I take going to the doctor very seriously. When I’m sick, I make an appointment. And when I’m healthy, I make appointments, so that I can avoid getting sick for as long as possible. I want to understand where my health is now so that I have a framework for comparison for later. I want to use medicine as a preventative tool for my health as I age.

And researchers are discovering that this habit of mine might actually be tied to female longevity. Women are more likely to visit the GP than men and this may help us to live longer. So do the other healthy choices that, as a group, women make more than men do, like not smoking. Fewer women than men smoke, which cuts our risk profile for numerous diseases. Men also drink more than women do. Women are more careful about their nutrition, and taking care of food needs helps bolster strength and longevity. And women are less likely to take risks. Fewer risks equals fewer injuries, which equals greater health: unintentional injury is number three on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s mortality charts for men, and number six for women. Women also value friendship, love, and connection. We are social beings who invest in our families and in our communities and in our relationships. All these choices contribute to a longer life.

But female longevity isn’t just about our choices. Among primates like chimpanzees, females live longer too, and monkeys don’t make doctor’s appointments. So why do females enjoy a longer life span? Some scientists are looking for answers that are rooted deep within the genetic coding of our cells. The cells of men and the cells of women are not the same, and what makes your cells unique affects everything about you – including how long you live.

THE OLDEST WOMAN IN THE WORLD

Today, life expectancy is twice what it used to be, but it may still be forty years shy of the maximum human life span, which most scientists believe to be about 120 years old.

They base that opinion on people like Jeanne Calment, the oldest woman who ever lived. Jeanne was born in France in 1875 and passed away in 1997. When she was a year old, Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone. When she was thirteen, she met Vincent van Gogh. When she was eighteen, the Wright brothers flew for the first time. She lived through two world wars, saw infections thwarted by medicine, and witnessed the development of the Internet and contemporary medical technologies.

When she was ninety, a lawyer who was not yet fifty offered to pay her every year if he could take over her home when she died. She agreed. He died at seventy-seven, and Jeanne kept on going. She lived by herself until she passed away at the age of 122.

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE BIOLOGICALLY FEMALE?

You are a lady with millions of microscopic lady cells. Your female cells are special – the genetic information contained in each and every one of them is what makes your body biologically distinct from that of a man. Your female cells have unique characteristics, and so do the organs they make up, because female organs are sized and shaped differently than male organs.

For example, the female heart has a distinct architecture. Our heart is smaller than a man’s, with thin vessels arranged in a lacy pattern instead of the thicker tubes that connect a male heart to his cardiovascular system. Cholesterol plaques can settle throughout a woman’s arteries, instead of in a more obvious clump, as tends to happen in men’s hearts, making it more challenging to detect heart disease in women. That is why women experience heart attack symptoms differently than men do, and why they need different care at the hospital during and afterwards. Women are far more likely than men to receive an incorrect diagnosis about heart attack symptoms despite the fact that more women than men die of cardiovascular disease every year in the US and the UK.

Our hearts also beat in a distinct rhythm; any disruption of that rhythm results in an irregular heartbeat, called an arrhythmia, which can range in severity from mildly disruptive to life threatening. In addition, some medications and defibrillators – which have primarily been tested on men – have been shown to cause potentially fatal complications in women.

Women’s unique biology also translates into unique risk factors for disease. For example, women are more likely than men to develop depression, eating disorders, and anxiety disorders like post-traumatic stress disorder. Mental health issues are, in turn, a risk factor for a variety of other diseases. A twelve-year study of more than 10,000 women in Australia aged 47–52 showed that middle-aged women who were depressed have twice the risk of having a stroke compared to women who are not depressed.

But until the past few decades, nobody was talking about female cells, and it’s taken some time for the medical and scientific communities to realize just how important it is to consider the sex of our cells when it comes to healthcare. Today, with an improved understanding of how sex-specific biology affects research, diagnostics, and medical treatment, women are getting better care.

HOW DO CELLS GET A SEX?

Healthy people have forty-six chromosomes in each of their cells. Two of your forty-six chromosomes determine sex. The rest, the autosomes, determine pretty much everything else about you. Sex chromosomes only come in two varieties: X and Y. Women are XX and men are XY. The X chromosome is much larger than the Y chromosome, because it is a powerhouse: not only does it determine sex, it also contains additional genes and thus additional information. The Y chromosome is smaller and carries less information.

Your sex is determined by your father. When a sperm, which has twenty-three chromosomes, twenty-two autosomes, and one sex chromosome, collides with an egg, which has twenty-three chromosomes, twenty-two autosomes and one sex chromosome, fertilization takes place. The result is a complete human cell – called a zygote.

Since all of a woman’s cells have an XX, her eggs can only have an X. Since men have an XY, their sperm can contain either an X or a Y. It’s a toss-up. Will a fertilized egg become a female or a male? It’s all about the sex chromosome carried by the sperm.

If you are a woman, the sperm that made you carried an X chromosome. As the female zygote divided, all the cells it made were female, and thus, so are you. A zygote divides and replicates and divides and replicates and divides and replicates. And after all that replication, you’ve got a cluster of female embryonic stem cells that will eventually keep dividing to become heart cells and liver cells and skin cells and blood cells and brain cells. And all those resultant organs will be female organs made up of female cells.

The genes located along the X chromosome are called sex-linked genes; some of them are coded specifically for female anatomical traits, but other genes are responsible for more than three hundred genetic diseases, known as X-linked disorders. The fact that we have two X chromosomes in each of our cells may actually be one reason why women live longer than men – if one of our Xs contains a faulty gene, we have another X to step in. One example of this is red-green colour blindness, a common X-linked disorder. More men than women are colour-blind, because if the gene for colour is disturbed on their X chromosome, they don’t have a second one to use for backup. Having two Xs is like having an extra little black dress in the closet – or even better, having a few extra years of life in which to wear it.

HYSTERIA AND HAPPY ENDINGS

For centuries, the medical community viewed women as simply smaller versions of men with different reproductive organs – organs that were thought to make us mentally unstable. You can go to a library and view 1,500 years’ worth of medical journals – from classical Greek texts to Victorian literature – that record “hysteria” as a common diagnosis for women. The word “hysteria” is actually derived from the word hysterikos, Greek for “of the womb.”

If a woman seemed psychologically stressed, or she started forgetting things, or she seemed emotionally volatile, like she needed too much attention, a physician might diagnose her with hysteria. Remedies ranged from sniffing smelling salts to having sex. A single woman would be advised to marry. Married women were advised to sleep with their husbands or to go horseback riding. Alternatively, in a not uncommon practice, doctors and midwives would use their fingers to stimulate women to orgasm, or “hysterical paroxysms” – basically a happy ending at the doctor’s office.

As recently as the late nineteenth century, nearly three-quarters of the female population were deemed to be “out of health”, including women with “a tendency to cause trouble”. Since their issues generally couldn’t be resolved in just one visit, these women represented America’s largest therapy services market.

In 1980, “hysterical neurosis” was finally dropped as an official diagnosis by the American Psychiatric Association.

Just another reason to be grateful that you’re a lady.

THE FALL OF BIKINI MEDICINE

If you ask a female doctor in her fifties about the model for human anatomy she studied in med school, she will tell you about the 70kg (approximately 11 stone) man that was the example for her medical training – and his female companion, the 60kg (approximately 9½ stone) man with boobs and a uterus. Medical students were not trained to treat the male and female bodies as all that different, except when it came to the reproductive organs – the areas covered by a bikini. Hence the nickname for the medical education of the era: bikini medicine.

Bikini medicine was the product of centuries of misunderstanding about female anatomy that began with all that hysteria about hysteria. The fall of this antiquated model and the rise of our more accurate understanding of female biology is tied in large part to the strides made by a generation of thinkers and speakers and brave, determined individuals who demanded change as a part of the Women’s Rights Movement. The modern view of women’s health we take for granted today only began in the 1960s, as women in Western society sought information about their biology and demanded better-quality medicine, including better reproductive care and uninhibited reproductive rights. They made it clear to lawmakers and medical professionals that women’s legal rights and medical welfare were inextricably linked.

Here’s one example: the year that I was born, 1972, was the same year that the federal government allowed unmarried women legal access to birth control. Think about that. If you were a single woman in 1970, it was actually illegal for you to take charge of your reproductive system. In 1989, when I was seventeen, Congress allocated funds specifically for the study of women’s health. By the 1990s, 30 per cent of ob-gyn specialists were women, up from just 7 per cent in the 1960s. Their efforts, along with the efforts of countless other doctors and scientists, increased the focus and attention on women’s health, including the health of older women, setting the stage for the healthcare we will all receive in the years to follow.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF WOMEN’S MEDICINE IN THE UNITED STATES

1916:

Margaret Sanger opens the first birth-control clinic in Brooklyn. Ten days after it opens, the police shut it down and put her in prison. Contraception is illegal.

1916:

Planned Parenthood is founded.

1920:

Women get the right to vote

1960:

The birth-control pill is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

1960s:

The women’s health movement begins.

1963:

Congress passes the Equal Pay Act.

1967:

The National Organization for Women (NOW) is launched.

1971:

Ten per cent of medical students are women.

1972:

Eisenstadt v. Baird establishes the right of unmarried women to use the birth-control pill.

1973:

Roe v. Wade gives women the option of a safe and legal abortion.

1989:

The Supreme Court allows states to make abortions in public hospitals illegal.

1990:

Congress passes the Women’s Health Equity Act, and dedicates federal funds to research on women’s health.

1993:

Congress mandates that scientists must include women in clinical trials in order to be eligible for federal funding.

1996:

Perimenopause is defined by the World Health Organization.

2013:

It is reported that women taking the sleep-aid drug Ambien fall asleep while driving. At the urging of the FDA, the manufacturer of the drug cuts the recommended dosage for women in half.

2014:

The NIH mandates that female cells must be included in all federally funded medical studies.

HOW YOUR SEX AFFECTS YOUR DRUGS

During our visit to the NIH, we spent valuable time with Dr Janine Clayton, the director of the NIH’s Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH). The ORWH has been around for only about fifteen years. Its mission is to promote women’s health initiatives in the medical community, educate the public about issues related to women’s health, and fund programmes that explore the role of sex and gender differences in medicine. Dr Clayton and her team have been working for years to encourage her colleagues at the NIH to prioritize women’s health issues and needs in their research.

We asked Dr Clayton some questions about sex and drugs, and she told us that your female sex affects the efficacy and the potency of the drugs you take. This is especially important for Americans because, as a nation, we take a lot of drugs. But while women are being prescribed more medications than ever before, not all of those medications are properly tested for use by women. And it has been proven again and again that drugs don’t affect men and women the same way.

When we swallow a pill or get an injection of a vaccine, the medicine travels throughout the body via the bloodstream and is distributed to our tissues and organs. However, medicines affect women differently than they affect men for several reasons:

WE HAVE DIFFERENT ORGANS:

A female liver metabolizes drugs differently than a male liver.

WE HAVE DIFFERENT BODY WEIGHTS:

Men are usually bigger and heavier, and have bigger organs, requiring higher dosages of drugs than a smaller woman does.

WE HAVE DIFFERENT BODY COMPOSITION:

Women store more body fat than men do, and some medications are attracted to fat tissues. When a woman takes those drugs, they linger longer in our bodies, and their effects linger too.

WE HAVE FEMALE HORMONES:

Our hormones influence how our bodies process medications. Factors like oral contraceptives, the menopause, and postmenopausal hormone treatment could also affect how we respond to drugs.

Painkillers and anaesthetic drugs are absorbed and metabolized in a unique way by women, who have a 30 per cent higher sensitivity to neuromuscular blockers and in turn need smaller doses than men. Research has shown that males and females do not respond in similar ways to opioids like OxyContin, Percocet, and Vicodin. Some medications, like Valium, exit our bodies faster than they do men’s bodies. Others linger longer. In animal studies, males and females also react to withdrawal in different ways. It is crucial for us to be aware of these differences, because as a nation we are currently experiencing what the NIH has termed an “epidemic” of women overdosing on painkillers, with a dramatic rise in the number of women dying every year. And the highest risk of death from an overdose of prescription painkillers isn’t found among the young – it is found among women between the ages of forty-five to fifty-four.

But all this information is relatively new, and that’s because for a long time, pharmaceutical companies tested their drugs only on male cells, male animals, and male humans. This practice has led to a mountain of data that isn’t very accurate when it comes to prescribing drugs for women. Many of the studies we rely on today faithfully and obsessively record variables like time and temperature, but overlook the small detail of sex. Even when it comes to animal testing for drugs being developed to treat illnesses that predominantly affect women, sex isn’t always taken into consideration. That goes for human female subjects, too. Since hormones fluctuate over the course of a month, tests that use females can be a lot more complicated to analyze than tests that use males. Without taking hormonal shifts into account, it is impossible to determine how treatments might affect a woman over the course of a month. Pregnancy is a concern in medical testing as well. In the 1960s, thousands of pregnant women who participated in a study and took the drug thalidomide gave birth to babies with serious defects. That tragedy has had a lingering effect on the scientific community, making researchers wary of including women in drug trials at all. By not creating safer trials and including women, however, we’ve also lost the chance to gather important information.

Luckily, things are changing.

Since 2014, the NIH has required applicants for federally funded research grants to address how sex relates to the way experiments are designed and analyzed. This research is critically needed, because as you’ve read in this chapter, medications affect women uniquely – even everyday ones, like the flu vaccine. A woman requires half as much flu vaccine as a man to potentially produce the same amount of antibodies.

Women need appropriate doses of everyday and life-saving medicines that have been developed to be effective for our bodies. We need research that supports our sex, our cells, and our lives. The more knowledge we have of our female biology, the more we can advocate for quality care for ourselves as we age.

Over the course of my lifetime, women’s healthcare has improved dramatically. When I was a girl, the medical community was evolving in ways that would profoundly affect my life as a woman. I may not have been aware of the social changes that were swirling around me – and I certainly wouldn’t have understood that the advances being made in women’s rights were so closely tied to advances in women’s healthcare. Now I understand that, ladies, we have been living through history.

As we are writing this book, there are more than thirty million women between the ages of thirty-five and fifty living in the United States. Whatever health challenges you might be going through, anywhere in the world, you are not alone. We’re millions strong. We’re standing in the middle of a conversation that has been going on for hundreds of years, with hard-won rights and knowledge bestowed on us by previous generations of women (and men).

And the changes are still coming.

WANT THE FACTS? ASK.

Whether you’re choosing a phone plan, buying new clothes, or ordering from a dinner menu – chances are you probably ask a lot of questions before making a decision. How many minutes will I get? Do these jeans come in petite? Is the pasta homemade?

Asking questions helps you make sure you’re getting what you want and need. So do you bring those same sleuthing skills to your GP visits? Unlimited texting, the perfect pair of jeans, and an amazing meal are totally worth the time it takes you to assess your options – and so is your healthcare.

When we were at the NIH we met with its director, Dr Francis Collins, and asked him what he thought the public needed to do when it comes to healthcare. He said that the most crucial thing we can all do is pay attention. Ageing research (and other medical knowledge) is constantly evolving. We can’t rely on medicine developed twenty years ago for our treatment today.

The only way to stay informed is to ask your doctor lots of questions, and to keep on asking if you still aren’t sure of the answer. We talked to doctors who said they were amazed by the LACK of questions they receive from patients. They told us their patients don’t always ask about the medications they’re prescribed – what they’re for, what they do, what the benefits and risks and side effects may be. They all encouraged us to encourage you to ask more questions.

Everyone deserves to have a GP who listens to their questions and takes the time to answer them, who will discuss alternatives and options, and who respects and takes seriously their symptoms.

Dr Seth Uretsky, a cardiovascular specialist and medical director of cardiovascular imaging at Morristown Medical Center in New Jersey, often sees patients who feel their symptoms have been overlooked by physicians. He believes that it’s important to trust and feel comfortable with your GP, and that finding one who listens, gives you time, and explains his or her thought process is crucial. And the data underscores his point: when patients feel understood by their GP, outcomes are better.

If your GP doesn’t seem to have the time to listen to your concerns, or if you feel that he or she doesn’t take your questions or symptoms seriously, it’s time to find a new GP.