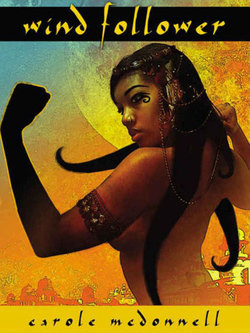

Читать книгу Wind Follower - Carole McDonnell - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSATHA: Sowing Moon—First Cool Moon

In those days, I could not sleep, for grief had rolled into grief: a dear cousin slain, a sister kidnapped, our clan destroyed and scattered. The last sorrow—a harrowing journey to a far region where comfort of family and friend could not be found—was the worst of all. My mother changed, growing more sullen than before. She wept continually, crying aloud and begging the Good Maker to roll back time and to bring back her lost youth, her lost fortune, lost clan, and stolen child. So as I paced outside the college courtyard, listening to the songs of the young men inside, I could not help but be overwhelmed with grief.

Many young warriors had died during the forty-year war, and as the songs floated upward and away from me, I imagined their lives also flying away from us. Because of the war, I had not had the privilege of education. I had not studied the dead languages, as one should. Born to wealth but reared in poverty, I did not long for what I did not have. But often I found myself wondering about my lost education. Which language is being sung? I wondered now. Paetan or Seythof? What are the words of the song? As I pondered this, Mam raced up to me.

“What are you doing here, Satha?” She peered out at the marketplace. “Didn’t I tell you to meet me in front of the sword seller’s shop? Standing here, listening to men sing the day before the Rose Moon, a day when love is on the minds of all! People will say Monua’s daughter is so poor and lonely, she went searching for a man.”

The college lay on the western arc, opposite the Rock Gate and a stone’s throw from the sword seller’s shop. I gestured toward the courtyard wall. “I heard the collegians, so I came closer to hear the song. Do you think Father can tell me what this song means? Do you think they’re singing about the Angleni wars?”

“The Angleni!” She spat out the invaders’ names with such venom I feared the afternoon would be filled with her recounting of bitter memories. “I don’t want to hear about them, even in songs bewailing their cruel deeds. Come, hurry to the sword shop.”

“But Father doesn’t trade swords. Why should we—”

She glanced back over her shoulder as we sped along. “You’re asking too many questions, Satha. Hurry! We have little time.”

“Why should not I ask? You ordered me here and then took so long getting here—” I noticed newly applied kohl around her eyes. She had changed her kaba too. The kaba she had changed into was torn and ragged along the hem, far worse than the one she had worn earlier. The gyuilta thrown over it had been relegated to the scrap heap. I understood then that she had determined to appear both lovely and destitute at the same time. This decision provoked even my curiosity—and I was not one who was naturally curious. I tried to ignore this wonder beside me fearing that asking questions would only drag me into affairs I wanted nothing to do with.

Her eyes busily scanned the eastern arcs near the Great Garden, and peered past the children playing tunes on their reed pipes and bamboo drums near the Sun Fountain and the Water Clock. They looked about the wide circle of the marketplace, and down its adobe-bricked streets fanning out from the Sun Fountain. How could I not be curious? Her eyes searched all the arcs and all the radii of the circle all at once.

At last, she took a brief rest from her surveying and said, “I wish you hadn’t been standing near the college wall.” She tugged my braid hard and her embarrassed eyes shamed me in spite of my innocence. “You’re not young or marriageable anymore. People will think you’re desperate.”

“You put kohl on your eyes—something you never do—and you’re accusing me of looking for an assignation?”

“Daughter, it’s good to have allies.”

I could only sigh at this sudden change of subject, so weary was I from sleeplessness. I only thought: So she’s scheming again? And now we’re getting around to her plot.

“Perhaps the shaman can make you something to help you sleep.”

She shook her head. “You let life bother you too much. When you get to my age, you can sleep even in the worst disasters, even when family members are stolen from you.” She held my right forearm firmly, tightly. Then, clenching my wrist, she dragged me further away from the college courtyard. How I wanted to tie my gyuilta’s trailing hem and scale the wall! To lose myself in song and learning and to leave the poor sad world behind!

“Today is the day that changes our lives, Daughter.” Yes, she had contrived some mad scheme! What Mam was like before poverty, grief, and the Angleni invasion unhinged her mind I don’t know. I suppose she must have been less manipulative, but who can truly know what occurred before one’s birth? Like my lost sister, I was born after the war began, after sorrow and repeated Angleni truce breaking and atrocities had embittered my mother.

“Ydalle sent a news runner to our shop this morning,” she said.

An image of a stout nervous Theseni woman and a long-haired youth flashed across my mind. “The boy in green leggings?” I asked. “With the butterfly beadwork?”

She nodded. “The Pagatsu markings. The boy was one of Taer’s servants.” She raised her eyebrows, indicating I should be impressed that Taer’s servant had visited us. I shrugged.

A self-satisfied smile spread across her face. “Even though the Angleni destroyed our livelihood, they haven’t destroyed your Mam’s ability to keep old friends and make new ones. Even here, the Good Maker has blessed us with allies.”

She was right, of course. Mam was greatly liked. In our native village, it was even rumored she was to be appointed to the council as a Beloved Woman. She would have sat among the Kluna clan elders of the Theseni tribe. What honor that would have brought her! But we had left the Kluna region and had come to Satilo. I had thought we were merely fleeing the Angleni who now occupied so much of our old region, but I had always wondered why she had chosen Satilo, a town with a population that was mostly Ibeni.

She craned her neck, glancing behind me, then spoke through cracked front teeth as we loitered near the sword seller’s shop. “You’ve heard your father speak of his old friend, Taer, haven’t you? The Disa of Scha Menta’s army?” Her eyes glowed with scheming.

“The First Captain everyone calls General Treads Lightly? That Taer?”

“Think of it, Daughter! We know the Disa of King Jaguar’s army personally!”

I drew in my breath. Partly from sleeplessness, partly from disgust and wariness. Her plot was becoming all too clear, even to my muddled brain. “Mam, Father told you not to communicate with Taer.”

“We’re not going to ‘communicate with’ him, foolish girl. We’re simply going to accidentally bump into him. Such things happen. Especially in markets. Of course, if one bumps into someone, the law of hospitality declares he must be invited into your father’s shop for a meal.”

Father’s shop was dingier than all the shops in the market. Grief and illness had tied all our hands and we hardly had strength to make it hospitable. “Mam, reconsider this.”

“Is it wrong to invite an old friend to a meal?” She scratched her head, something she always did when hatching a plot. “Such things also happen, don’t they?”

“And why do you want to invite him to our shop?” I asked, already knowing the answer.

“Why? So he’ll see our poverty, of course!”

“Of course.” Why one person would want another to see her poverty was beyond me.

“Taer is an honorable man.”

I suddenly understood all.

She glanced this way, then that, as if the trees themselves were conspiring against her. “He has no patience with commerce. No, he was never one to dwell on such earthly matters. Rich men can afford to waste their time studying the gods. Not that I judge the man. Should General Treads Lightly be seen in the streets bartering, selling and buying when he has servants to handle his money? Even so, today.... “Her voice trailed off.

“Today?”

“Today, Daughter, he comes to the market. Oh, I’ve been waiting so long for this.”

Her face beamed as if a star of ecstasy surrounded it. “For the first time in eight moons!” She almost danced an Ibeni two-step. “Ydalle says Taer’s son wants to buy a sword, and when that boy wants something, well, you know how the Doreni spoil their children. So Taer will be helping him choose.”

“Doesn’t Taer have military underlings who can—”

“Tsk, tsk, this boy’s his only real child! And a sword—”

I could not help myself. “He has an unreal child?”

Her eyes hinted at secrets. “Well, there are other—shall we say—concerns.”

“Concerns, uh? Those concerns are no concern of mine. But if he’s so close to Our Matchless King, Taer could easily ask the king for a sword for that spoiled brat of his.”

“Taer’s not one to push himself forward. Ydalle says this boy wants an untested sword, one that doesn’t remember old victories.”

“Can’t he wipe off the old blood like poor warriors do?”

Mam glanced upward at the sun and then at the shadows looming on the ground and waited, pacing. She flung her hand this way and that as if we were discussing some great business. She even lifted my own hand, encouraging me to make the show more believable. Time passed, however, and I suppose she became tired with all that acting. She stood in front of me frowning. Although tears welled in her eyes, a flood of amusement inside me began to overflow. Despite my sleepiness, I laughed at what appeared to be a failing scheme.

“Laugh if you wish!” she shouted, her face betraying her heart’s worry. “You’re obviously not smart enough to know you’re laughing at your own misfortune. Have you so easily forgotten that Kala’s parents had to sell her to pay off their debts? And Kala was pretty! Look at you! Twenty-four years old, too dark, and too mouthy! No wonder you’re unmarried! My luck was never good.”

I had gotten used to the thought of living unmarried. Theseni men valued girls with honey-colored skin. Dark women had little chance of being married and even less chance of being loved. Yet, I had learned to see my dark skin as a blessing from the Good Maker. During the war, many young men from all the three tribes had been killed. Those who had been born in the years before the war ended had been so spoiled by doting mothers they often turned out to be cruel husbands.

“I’m tired of all this poverty.” A despairing frown spread across Mam’s face. “Tired of creditors and old clothes, tired of eating barley and vegetables, tired. But it’s my own fault. I should have listened to my mother. I was in love with Nwaha and I didn’t realize how draining a weak man could be. So this is how my own strong will rewarded me.” Tears poured from her eyes, which she immediately wiped away with the fringes of her tattered gyuilta.

Then, as if she were tightening her mind, she tightened the gyuilta’s loose belt. “If Taer finds out how poor his old friend has become, help won’t be long in coming. Who knows—he might even give us some money for your dowry! A massive dowry will make up for that dark skin of yours.” She searched the distance as if seeking a lost hope. Then a smile suddenly lit her face and she seemed much younger than her forty-two years. Such joy I hadn’t seen in months. I knew without being told that Taer was in sight. “He’s come. Look! Over there, near the horse dealer! No, don’t look! He’s the Doreni in the buckskin leggings and the green tunic. No, no, I told you not to look.”

I looked, and saw a muscular well-built man standing beside a slender, almost fragile-looking boy. The boy’s unbraided waist-length black hair flew wild behind his back, as if the wind delighted in playing with it. Neither boy nor man cloaked themselves in the finery of the rich. Both wore green tunics and green caps embroidered with their butterfly clan pattern. Their clothes seemed woven from cotton, hemp or other common fabric; neither wore pearl-encrusted gyuiltas, as the rich were wont to do. The older man wore boots, the boy soft leather shoes with the clan markings. Although the cold moons were barely past, their heads, arms and shoulders were uncovered. When I saw how the man’s braided silver hair glistened, and how his body exuded strength and quiet power, I spoke without thinking. “Indeed, Mam, even from this distance Taer is good to look at.”

“Wait until you meet him!” She smoothed out the kohl around her eyes. “His nose looks like the curve of a bear’s back as it turns away to protect its young.” She breathed a long wistful sigh. “Beautiful jade-gray eyes. Almond-shaped like all the Doreni—but kind, not fierce like the other slant-eyes. He wasn’t one for war when we were young. How he rose so high in the King’s ranks, I’ll never know. He’s too pale, though. Almost as light-colored as an Ibeni. If he had a little more cinnamon in his blood, like most of his people, I would have chosen him when my parents asked me who I wanted to marry. Yes, and our lives would have been much different. But, the Good Maker forgive me, I was foolish and love-struck and I chose Nwaha. Your father had happy, hopeful eyes then. He was a nice brown, too. Dark, but not too dark. He was weak, although I did not know it then. Yes, that was my mistake—”

“Being honorable is no weakness, Mam,” I said, interrupting her. Mam’s bitterness against Father was like boiling water—always seething over.

“You can call it whatever you want. You’re not married to him. The past is gone, though. Taer’s married now and even if...” Her voice trailed off, then she spoke again. “Yes, he’s married. Waihai! Bad luck all three times. Ydalle says his third wife is the worst of his misfortunes.” She bent forward and whispered conspiratorially, “An adulteress.”

I shrugged, so she added, “The mother of a bastard child.”

Gossip against the rich is all the poor have to digest, but gossip always upsets my stomach. When I didn’t bite at her tidbit, she said, “I’ll tell you that little story later.”

“Mam, Doreni women who commit adultery have their noses cut off, or they’re stoned or cast out into the marketplace. I’ve heard no marketplace gossip that Taer has done this, and warriors aren’t known for indulging wayward wives. Tell Ydalle to stop spreading false stories.”

Mam clutched her chest as if some great disappointment weighed on her heart. “Why the Ancient One gave me a daughter with whom I cannot share my heart—I don’t understand!”

“Ask the Ancient One. Surely he knows we would both have been happier if I had been born male.”

She winced, but didn’t answer me.

“Do not make a fool of yourself with this rich man, Mam. Let me travel across the Lingan Plains to find work. I’ll—”

“No! Never! I’ve lost one daughter. I won’t lose another.”

“Or you can hire me to an Ibeni farmer across the river.”

“Did you not hear me? I said—”

“But, Mam, I have strong hands. I can—”

“Those Ibeni bleed even their own children dry. No, no blood-work for my daughter, and no travelling to parts unknown either. Ydalle says Taer’s house is full of servants and former captives. When a woman marries a fool, she learns to create her own destiny. One more servant won’t rob him. Maybe he’ll hire you as a favor to Nwaha. The Doreni are unlike the Ibeni. They don’t worship gold as much. Perhaps Taer will make you his concubine.” She grinned and raised her eyebrows.

“I don’t want to be a rich man’s second-status wife, Mam. I don’t even want to marry.”

“Stop frowning like that! It makes your forehead look ugly.” In those days, unmarried Theseni women wore a sheer full veil that reached from the forehead to below the neck. My mother lifted my veil. With the hem of her gyuilta, she wiped some unseen, unfelt something from my face. “Work with the little charms you have. Learn to smile. A girl as dark as you can’t afford to be too high-minded. You want your father sold into slavery for his debts? Is that what you want?”

Her face contorted into the smug triumphant smile she always wore whenever she bested me. “Now, daughter, throw your gyuilta over your shoulders and walk with me, your arm in mine. The Creator will make my old friend recognize me.”