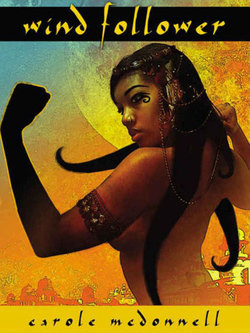

Читать книгу Wind Follower - Carole McDonnell - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSATHA: Sudden Betrothal

Rose Moon—Second Cool Moon

The next day when a valanku pulled up to our shop and three linen-clad men stepped out of it carrying three silken bolts of fabric—pale green, reddish purple, and ocean blue—our Ibeni neighbor came running into our garden.

“Where did the money come from to buy all this finery?” he asked Mam without even a greeting.

Mam took the silks and said, as if they were nothing new, “My Satha’s promised one is always sending lovely gifts to fulfill their age-old marriage vows. These are for her half marriage ceremony, today.”

“But this is news!” The Ibeni fingered a small porcelain frog fetish about his neck. “The first day of the Rose Moon is very propitious. Why didn’t you tell anyone?”

“To speak of one’s good fortune before the blessed day arrives is to invite the evil eye,” Mam answered, glancing at me. “I’m not so stupid as to parade my good fortune when there are so many jealous people around. I’m sure you understand what I mean.”

The Ibeni nodded knowingly, and Mam waved Taer’s servants away, as if she were already their Arhe, the Chief Mistress of the Pagatsu households. As I started following her in, the Ibeni whispered to me, “The valanku bears Taer’s markings. That rich little Doreni boy worked quickly! One day he’s asking questions, the very next he sends you marriage raiment. Waihai! A boy of such determination will make a good husband.”

“Mam,” I said when I went inside, “don’t tell that lie anymore about Taer’s son being my promised one. Our neighbor knew you were lying. Since I’ve never heard of this promise I had no good answer to—”

“Waihai!” Mam shouted. “Of course there’s a promise! But Taer had grown rich and rich men often forget to honor their promises to poor friends. No use giving you false hopes.”

It was one altvayu after another. In those days, altvayus—little lies—were an art and they came in all forms: the protective lie, the etiquette lie, the covering lie, and the hospitality lie. By the time I began to wear the scarfed long veil I had heard so many prevarications, ambiguities and ambivalences, I considered every word as veiled as I was. Altvayus were such a necessary virtue that no one believed anything anyone said. My only response was, “I had no hopes, false or otherwise.”

Mam studied the fabrics with a seamstress’s calculating eye. “The green would probably be the best choice for you,” she said. “It will work best against that dark skin of yours. Plus green is their clan color. What do you think of a dress in the style of the Ibeni Kelovet clan? It’s the style now, and every woman is wearing it.”

The long puffy sleeves I could accept and I could manage not to trip over a Kelovet veil that trailed along the ground. But I objected to the low square neckline.

“Waihai!”Mamshouted.”Youngmen,howevervirtuous,areentrapped by their eyes. You’ve got two good pillows for his eyes to rest on.”

“But,” Father added, coming in from the back room, “we don’t want her pillows hanging out. We’re Theseni, remember.”

By nightfall, I was seated in a purification bath of myrrh and aloes trying to accept this sudden engagement as I watched Mam sew a betrothal dress I wanted nothing to do with.

Father spoke through the slatted curtain, which separated my room from my parents. “You’ve been quiet all day, Satha. Have you accepted the blessing the Creator has given you?”

Mam poured aloe juice on my head. “She’s too cynical to see anything as a blessing!”

I tightened my lips against the aloe’s bitterness, but the acrid taste crept into my mouth.

“It’s good luck to get it on your tongue,” Mam said, when I wiped the juice from my mouth. “Bitterness on the lips before the wedding means sweetness in the bed afterward.”

“If that’s true and everyone takes these stupid baths, why are there so many bitter marriages?”

She grunted, then returned to her sewing.

“I don’t want you to think the young man is merely marrying you for the sake of the promise,” Father said. “He’s quite interested and was very involved in his father’s choice.”

I squirmed in the large clay wash basin. “Yes, Father, I heard as much last night.”

Mam bit off a piece of sewing thread. “Be careful you don’t break that basin. I borrowed it from Uda. That hyena never—” She paused, then suddenly started laughing. “Layo-Layo! Yes, yes! Break it, Satha. After you’re finished bathing smash it to bits! We can now afford thousands of better basins. We’ll give her a gold one to replace it. Can you imagine it, Nwaha? Our daughter is marrying Taer’s son! The son of King Jaguar’s Chief Warrior.”

“Not something I had ever imagined in my wildest dreams!” he answered, and then as if catching himself, he added, “But, of course, when we were young men Taer wasn’t a captain. And when you held little Loic in your arms you—”

The trouble with altvayus was they often spun out of the weaver’s control. Father was not good at spinning lies. If he continued weaving this one, he would not create a tapestry, but a tangle no one would be deft enough to sort out.

“So, although I’m a woman past marriageable age and without a dowry—”

“Satha,” Mam shouted at me, “you don’t need to know all our business.”

Father added, “Should we not provide for you? Think of Alima. Look what happened when we told her about our money problems.”

Tears came to my eyes when they mentioned Alima, my beautiful and lost sister. She had traveled with three women across the Lingan Plains into Theseni territory where they had meant to find work. But women traveling alone are powerless, especially if they left their home regions. Lascivious Ibeni might rape them, patriarchal and pious Theseni could enslave them. Alima’s beauty had caught the eye of Kujhan, a Theseni man from a vicious clan. She found nothing in him worthy of her love. This did not matter to him. On her seventh day in the region, she found Kujhan had “married” her, using proxy. Although Alima hadn’t attended her “marriage,” the Theseni men considered her to be married. After that, she could not leave that town without her “husband” Kujhan’s permission. He never gave it. Starving and alone, she at last relented and went to his bed. She now lived there, an enslaved “wife,” held captive by the man whose heart she had inadvertently captured. Worse yet, they followed the old Theseni custom in which a wife was shared among her husband and his brothers until the brothers married. The only mercy she received was death.

“The only power poor men have is their power over women,” Father said, shaking his head. “And the cruelty of poor men is worse than the arrogance of the rich.”

“Husband! You’ve spoiled this child by allowing her too much freedom. Her dark skin she can’t help, but if she weren’t always reading those religious scrolls, she would have been married already. Poor men can’t be choosy. But your—”

“Mam, I have no desire to marry this child.”

“I can’t break my promise to my friend, especially since he’s sought to fulfill it after all these years,” Father said. “As for his age, custom will be upheld. You will not lie in his bed until the Restraint is over and the year mark arrives. When the full marriage will take place, you’ll have become accustomed to one other and you won’t mind his age.”

“A year? Time enough to prove someone hasn’t impregnated me, I suppose,” I said, speaking the obvious.

Mam took her eyes off her handiwork and gave me a warning look. “Learn to watch your words, girl. Don’t go starting rumors about yourself. The half marriage is the way the Doreni do things. They have their reasons. You don’t want a clan war breaking out because someone didn’t get the news about such an important occasion. These year-long half marriages ensure that everyone—far and near—gets the chance to approve of you.”

“If the Doreni weren’t so aware of alliances,” Father added, “they would not have conquered our people five centuries ago.”

“You’ll have to learn to think like a Doreni,” Mam said. “Think about things such as enemies and alliances, learn to pretend to like people you don’t like, and hate people you don’t hate.”

I groaned, but she continued. “You can do it. You have to. A person can’t live without allies in this world. Certainly not in a great man’s house, with people of another tribe. Consider yourself lucky it was a Doreni boy who fancied you. All you have to worry about are slantyeyed children. Imagine if you had captured some Ibeni boy’s heart. He would have kidnapped you to save his greedy family a dowry and I’d be wandering the world looking for you.”

“I doubt you’d go searching the world for me. I’m not Alima, after all.”

She ignored me although she knew my words had shown my heart. “Remember to size him up. Learn what impresses him. Anticipate what he wants. The important thing is that he like you. If you behave without common sense, your father and I will end up on the streets. If the boy lusts for you, give in. Bend a little. Waihai, look at that pious face of yours! Even the holy ones tasted the joys of the flesh before they locked their yphers away. Think of it! During the Restraint, you’ll be living in Taer’s compound in the guest women’s quarters. Isn’t that better than living here? All that food! They’ll fatten you up. Skinny women are no good in bed.”

“Could we not talk about such things, Mam?”

“All your mother is saying,” Father chimed in, “is that if he likes you, the rest of the Pagatsu clan will like you too. Just show yourself to be a woman of good sense and diplomacy. The Doreni like that.”

“And take care to watch the women,” Mam warned. “Women can make or break you.” Her eyes suddenly filled with tears. “Your poor sister, this marriage should have been her destiny.”

Her words stabbed my heart. I winced, but if she noticed, she hid it well.

“Daughter,” she said, wiping away her tears. “No woman in Satilo would push Loic out of her bed. I’ve seen the boy’s face. His body too. He’s a beautiful one. Good to look at. Haven’t I seen your eyes light up beneath your veil when a beautiful man walks past you in the marketplace?”

She started dancing—a thing she had not done in many moons—and began singing an old song:

“A rich man’s son is a good catch.

He’ll be a lord for you to wait upon.

A kind-hearted husband is a good find.

His heart is as generous as any woman’s.

If such a husband is found when he’s young,

While he wears his youth cap

Teach him to wait upon you.

And he will nurse you when you are old

And in grandmother’s leggings.”

They both laughed as the song ended. She then held up my betrothal dress for me to see. “Quick! Out of that bath! Let’s see how you look!”

I put on the betrothal raiment and before I could stop her, Mam was holding a mirror up to my face. Unprepared for it, I closed my eyes to my reflection.

“Look at her flinching,” Mam said. “Even though she looks as beautiful as Queen Butterfly in this dress. What’s wrong with your daughter, Nwaha, avoiding mirrors like that?”

“The veil is nearly-transparent,” I said, “and it extends only from my forehead to my neck, not covering my breasts as it should. And there’s no scarf to cover my head. Am I supposed to behave like an Ibeni whore in order to make my husband love me?”

Mam looked at me, staring wide-eyed. It was clear she thought the answer to my question was obvious. “You need no head-covering now. Doreni women don’t wear them. Besides, your husband will cover your head now. But since you’re so pious, I’ll try to repair it.”

The next morning as I took the second purification bath, Mam put the finishing stitches on the dress: she made its neckline even lower. She hid the dress from me until moments before Taer’s valanku arrived; I had to enter the carriage in a betrothal dress which exposed so much of my breasts that even the holy ones would have fled.

I had seen many betrothal processions wind through the city. Whether rich or poor, the betrothed women would be driven through the city streets with foreheads and shoulders so weighted with jewelry their heads could hardly be seen. Such spectacles had always offended me, but perhaps I had only been envious all along, thinking such fortune would never be mine.

My parents sat behind me in the open carriage, Mam praising the Good Maker for all our blessings and fingering the long strand of pearls around my forehead and the gold bracelets on my arms. The sunset-colored stallion—a gift from Taer like the jewels, but to the rest of the world a part of my dowry—pulled the cart on which our two goats bleated contentedly. My future husband’s male servants rode on black stallions behind us, as if we were royalty.

“Look how glum she is!” Mam said at last. “Sitting there as if she’s one of those war criminals she feeds. She isn’t the least grateful her New Father has paid all our debts, and covered her with finery.”

“Such a dowry!” Father said, shaking his head.

Mam leaned back like a queen resting on a throne. “Not that Taer cares about such things. As far as he’s concerned, Satha’s now the most valuable jewel in his household.”

Small though our betrothal procession was, crowds gathered to watch us pass. Our neighbors at the market and our creditors shouted, “Who would have known Nwaha would have received such sudden blessings?”

Father shouted back, “Sudden blessings come from the Good Maker. May His name be magnified.”

Mam, however, seemed to be thinking only of our dead. “Imagine,” she kept saying, “how wonderful this procession would be if all our clan—yes, even the lost, kidnapped, and murdered ones—were following behind us! Waihai! Perhaps they are!” She turned and waved to their spirits just in case. “Imagine it! In our younger days, Satha, we had a hundred times such blessings.”

We wended our way through the city towards Taer’s Golden House, my parents’ faces more carefree than I had seen in years. Mam no longer looked like someone who cried every night about the fate HaZatana had brought her. Such were the blessings of selling one’s daughter into a wealthy marriage.

“Daughter,” she said, suddenly becoming serious, “when you’re settled, remember you owe your good fortune to Ydalle. Other servants have gone on with their lives and forgotten the kindness with which I treated them. But Ydalle always had a loyal heart. Treat her well and reward her. You’re not as shrewd or as subtle as your elders so it’s well to listen to her advice.”

“I will, Mam.”

“As for other servants in the Golden House, choose for yourself those of the lowest place, the rejected ones, the ones who have little power in the house. They’ll be grateful for the kindness, and they’ll never abandon you. But choose only the kind-hearted ones. To lift a powerless ungrateful person to power is to create a proud and jealous enemy. Even so, make them know their place. If you befriend them too much, they’ll forget they’re not your equal.”

From within her gyuilta sash, she retrieved a small pouch—a shaman’s puha. “I know those pearls around your neck and waist are supposed to ensure fertility, but Old Yoran says I should sprinkle you with this. It’s the dust from our ancestral burying place.”

“Old Yoran keeps sepulcher dust from our ancestors at hand?”

She inched forward and held the pouch near my neck. “He traveled long last night to get this.”

“Mam, do not shower me with dead men’s bones.” Before I could finish—at the very moment I was telling her not to—she shook the packet. Powdered bones rained down over me. My flesh crawled.

Once again, my wishes didn’t matter. It angered me. And too: I was afraid. I felt I had received a curse instead of a blessing, that the sprinkled puha had turned my life towards death. “How many mothers have gone to witch doctors,” I shouted at her, “hoping to bless their children with such spells only to open their lives to evil spirits!”

“You’re entering a house without our tribal spirits,” she said, shouting me down. “You need to bring your ancestors with you. Or else, who will protect you and give you children? You’ll be useless to the boy if you don’t have children! You don’t want him to take a second wife because you’re childless, do you? A woman without children can’t expect a marriage contract to protect her.”

“You should have asked the Good Maker to bless me. He’s distant, but even when he destroys, he seeks my good. Unlike these spirits who always want something.”

She gave me a playful pinch that hurt more than expected. “When I was younger, my girl, mothers always pinched their daughters on their wedding day. To prepare them just in case their husbands beat them.”

I was unsure if this was true or merely something cruel spoken to disturb me. It would not be beyond Mam to curse me so that she might later be seen as the heroine who cures me, I thought. I was horrified to hear myself saying, “Mam, what if this boy turns out to be evil and dissolute? If he does beat me, promise you’ll help me appeal to the elders for an annulment.”

A smirk flickered on her face, as if she was glad her cruel comment had troubled my heart. “It is true that kind-hearted men often breed selfish children. But if the boy is truly evil, wouldn’t he use his power to destroy you if you tried to divorce him?”

I stood open-mouthed in front of her, and my obvious worry and distress brought a self-satisfied smile to her face.

“Mam,” I said, “I don’t want to marry him. Perhaps I’ll be lucky and during the half marriage he’ll find something distasteful in me and cast me out.”

She looked at me as if I had lost my sanity. “If he casts you out, you will be good for nothing except to be a holy woman or to enter an Ibeni brothel.”

“But why should I be good for nothing if he rejects me? A half marriage is a trial period, is it not?”

Father took my hand and held it firmly. “For the man, yes. Not for the woman. Daughter, you’re old enough to know what the law says is one thing, and real life is another. An annulment after a half marriage is worse than a divorce. People will think he found something unclean in you. At least a divorce after the full marriage means there was some respect and honor in the beginning.”

“And you get to keep your marriage gifts,” Mam added.

“Daughter,” Father said, “all you have is your intelligence and your kind heart. Those aren’t good currency in the marriage market. If Loic inherited the traits of his Desai mother, he already loves you deeply for reasons we cannot know. If he is like his father, he will never wrong you. Haven’t you washed the feet of poor refugees and cared for the dying? The Good Maker has blessed you because of this and will continue to bless you with many good things and with virtuous, wise and good children.”

Songs floated about the college as we rode by. I leaned forward to listen to them, trying to keep my mind off my fears.

“What are the words of that song, Father?” I asked. “You studied the dead languages. You must know their meaning.”

“It’s a song about the Good Maker—a Doreni Desai prophecy about a man being wounded in the house of his friends, a warrior whose clan turned against him.”

“I’ve heard that prophecy,” I said.

“That is why the Doreni consider inhospitality such a great sin. The traitor against the Savior forgot the laws of hospitality.”

Mam interrupted us, “Enough of religion! What good has it done any of us? We’ve been generous to the poor, and what did we get? Did the Good Maker protect us when the Angleni destroyed our land? Stop thinking about impractical things. You’re only getting me angry. Think about your wedding night like a normal girl.”

The wheels of the valanku turned smoothly and evenly underneath us, as if a perfect lathe had rounded them. The soothing regularity of the horses’ hoofbeats should have pleased me. Yet, the wagon wheels echoed like millstones grinding millet seed to powder; the horses’ hooves seemed to be trampling my heart.

As we approached Taer’s Golden House on the outskirts of Satilo in the far reaches of Jefra, near the edge of the Great Desert, Father turned to me. “Daughter—” he frowned as if he had sad news to tell “—I have a thing to tell you.” He exchanged a quick glance with Mam. “It isn’t so very bad....”

“Speak it, Father.”

His eyes avoided mine. “Health, my daughter, is a blessing that not many people have.”

I studied Mam’s face. “Are you sick, Mam?”

“It is someone else who is ill.”

“It isn’t a fatal illness,” Father added, too quickly. “And no, I’m not ill either.”

I understood. “Loic? Is he the one?”

They nodded in unison and looked at each other, as if waiting for the other to speak first.

“Is it fatal?”

“Not of itself!” Father said, again too quickly. “Bu—”

“It has its dangers,” Mam said.

“Does he have the mosquito illness?”

“Daughter,” Father could not help but laugh, “you always think people have the mosquito illness. There are other illnesses in the world.”

“What illness is it?”

He spoke the words almost too softly. “The falling sickness.”

A long-forgotten memory of a young girl in our old village appeared in my mind. For no reason, she would fall to the ground and foam at the mouth. I saw my future, one filled with sick children, an invalid husband. I did not want to bring healthy children into a world so full of sadness and cruelty, and now I was to bring ill children into it.

“It may not affect your children—” Mam said, knowing me well enough to see my thoughts.

“Did I say I wanted children?” I snapped. “I don’t even want to marry! And now I’m—Two days ago I was free to wander as I chose. Now I’m forced to worry about the health of a boy I don’t wish to marry, and the safety of children I never intended to bear. Why have you done this to me, Mam? You should never have allowed this rich boy to usurp my life. You would never have done this to Alima—”

Mam looked at me hard; I grew quiet. Shame and grief overwhelmed me. “Forgive me,” I said. “I accept what the Good Maker sends me.”

“That religious reading of yours has taught you obedience at least!” Mam said. “Alima was naturally good, however. She never needed those scrolls to learn obedience. Listen, Satha, I’m telling you of your future husband’s illness because it is a secret. The boy doesn’t even look ill, does he, my husband?”

“Not at all,” Father agreed.

“Only those within the clan and the household servants know it. Ydalle says, they have their ways of handling it. When he was young, a nurse was always with him. Now that he’s older, he doesn’t like people hovering about him. His teachers, bodyguards, his father, and the warriors usually find a way to watch him. When the disease comes on him, they prevent him from hurting himself. Then they leave him, right where he has fallen, pretending not to see his shame. When he arises, he is alone. He tidies himself and no one speaks of it. Ydalle says this is what everyone does, and it’s best if you learn to do likewise. You’ll shame him if you don’t, and no matter what you do, do not speak openly to him about it. You don’t want to shame one who is mad with love for you.”

“Mam, how can he be mad with love for me when he has only just seen me?”

“Perhaps he remembers how you used to tie his breechcloth!” Father said bursting out laughing.

“Obviously his ypher is ruling him,” Mam said, winking to Father. “That third leg gets men as well as women in trouble.”

* * * *

Within the golden brick exterior wall of Taer’s Golden House, fifty-eight Pagatsu households lived in harmony, or at least as much harmony as was possible for the Pagatsu. As I walked through the entrance gates into the large outer courtyard and surveyed the nearby gardens and the many minor houses that surrounded the Great House where Chief Taer lived, I realized the weight of good fortune the Good Maker had given me. On either side of the marble walkway, servants and noble ladies bowed before me. Their gold, silver and turquoise jewelry glistened in the sunlight.

Ydalle’s was the only face I recognized. A dark-skinned Theseni like me, she smiled uneasily and wrung her hands. Other Theseni faces peered out at me from the crowd, along with a few Ibeni and mixed-tribe peoples, but the majority of greeters and onlookers were Doreni. I reminded myself that although the Doreni seemed friendly enough, they were called the Fierce People, and the Pagatsu were the fiercest of all Doreni.

Ydalle seemed to share the same suspicious nature as Mam, and she hovered protectively about me as I took the honored place in the Gathering Room of the longhouse. This longhouse was not like those we live in now. In those days, a great chief’s longhouse was a fortress of stone and wood, and the circular gathering room where matters ceremonial and mundane were discussed was like a king’s throne room. Clan elders and their wives from near and far were present to examine me, but my prospective bridegroom was nowhere to be seen. Nor was his father.

All around the room, servants busied themselves. Although they all wore the stylized clothing of their respective clans, the edges of their leggings, breechcloths, undergarments, and tunics were embroidered with clan markings indicating they were in the service of the Pagatsu clan. Some were mixed-caste; others were warseed whose mothers had been raped by Angleni soldiers. Many warseed roamed the world in those days. Many begged in the streets, or were enslaved. Those in Taer’s Golden House were especially blessed.

Weighted down with jewelry, expectation, and doubt, I sat cross-legged on a pillow, as Taer’s clan questioned me about religion, philosophy, history, herbs and medicine, currency, etiquette, farming and agriculture. I answered well, I think, but who can truly judge such things? Loic was the headman’s son. Those who questioned me knew that to thwart a Doreni chieftain in his youth was to regret it when he was older. They therefore dealt gently with me.

All but one. The cold eyes of a silent beautiful brown-haired Doreni woman aimed daggers at me. Her gold-threaded dress—she was more richly dressed than all the others—indicated she was a noble in the clan. I realized as I looked at her that she made me tremble.

So rude was she that Mam whispered in my ear—a breach of etiquette, “I’ll tell you later why that one hates you. But what does it matter what a ghost thinks? She doesn’t even exist.”

I looked carefully, perceived. Mam was right. The captive women and servants eyed the noblewoman scornfully, and showed much disdain in their required duties towards her.

“Watch her,” Mam whispered. “She might be your future torturer, the one who makes it her goal to destroy you.”

A subtle flicker of her eyelid turned my attention to the slight auburn-haired boy sitting beside the woman. The only child in the room, he appeared to be about twelve or thirteen. He seemed so shy and fearful that I thought, If not for that red hair of his, he would disappear into thin air.

“That’s your husband’s ‘brother’.” Her tone implied he was no real brother at all. “Even so ... he’s here and not with the other children. Taer is a noble one.”

I twisted uncomfortably on my pillow. Suddenly so much needed to be known and understood.

The servants carried the ceremonial food into the room: barley, bala, and pomegranates for fertility, sunflower seed for prosperity, rose-jam for joy. Mukal and distilled pine sap flowed lavishly into goblets large and small; a feast lay on the large mosaic table—a garden of delights my husband and I could not touch until the appointed time.

Suddenly Mam’s elbow was digging hard into my side, and her eyes shone as if a bright star had appeared on the horizon. “Ah, your illustrious New Father has just entered.”

I looked in the direction she was gazing and saw a tall man about forty, athletic and sturdily built. I had expected the great Treads Lightly to dress in a war bonnet, bone hair-pipe breastplate, furs, and gems for the half marriage ceremony, but he wore a simple green tunic made of common hemp fiber and leather leggings. No dagger hung at his side.

“Not what I’d expect of a warrior celebrating his first son’s half marriage,” Mam complained in a low whisper. “But look!” She returned to her happier mood. “He honors you by perfuming his hair with carmi oil. That’s a month’s wages for the likes of you and me. Yes, that’s it. He wants you to shine, not himself.” Her eyes roamed his face. “The scar mars his face, but you can see how handsome he used to be.” She sounded wistful, but if Father was jealous, he didn’t show it.

Mam was right, though. How beautiful Taer was, how masculine compared to Father. The scar only added to his beauty. Father had no scar and it seemed a great pity he had none.

“New Daughter,” Taer said as he walked towards me. He almost sang the words, and the soft playful musicality of his voice surprised me. Seductive it was, and it put me at ease. Yet, it seemed strange to me that such a great warrior would speak so gently. He sat on the pillow to my right. “With her dying breath, Loic’s mother reminded me of my promise to your father. I have waited many years to keep it.”

I smiled beneath my veil, half-hoping the fabric of the altvayu would tear suddenly and bring an end to all pretence.

“Promised One of my son,” he said, bending towards me, “what do you think of this proposed marriage? I hope the old promise is not a burden to you.”

The question was etiquette, of course, and the right response should have humbly and quickly fallen from my lips. Yet, I didn’t immediately answer. A grievous fault, because it made me appear vain and ungrateful. Like armed warriors forcing an unruly enemy into a prison cell, Mam’s eyes threatened me if I challenged the marriage.

However, an old man sitting beside Taer nodded kindly in my direction. “Yes, Thesenya, tell him all your heart.” I would learn the man was Pantan, Taer’s uncle, and he was nicknamed “Thousands” because of the thousands he had killed. “Although the promises of parents bind children, we would not want an old promise to put a burden upon you, especially if your heart already belongs to another.”

“My uncle is right,” Taer agreed. “He was headman of our clan before he handed his vialka to me. I promise you no curse or vendetta will be laid on you or your children if you refuse my son.”

“My heart belongs only to myself, New Father. I hesitated speaking because throughout the land of the three tribes, women younger and more beautiful than I can be found. Good women of higher status and more worthy than I to marry one who wears a jade bracelet.”

Pantan grinned. Around me, others smiled. My directness mixed with my diplomacy had clearly impressed the Pagatsu. But Mam and Ydalle both slapped their right hands on their thigh so loudly and in such perfect unison, I almost believed they shared the same soul.

“Daughter,” Taer answered, “do not wrong your beauty. But hear me. I know only too well how cruel and bloodthirsty the hearts of women can be.” From the corner of my eye, I noticed a smirk flicker across the face of the lavishly dressed woman. “Cold hearts become even colder when wealth and innocent men are involved. What use, then, are beauty and wealth if they hide a cold heart? Were not Salba and Aroun cuckolded and poisoned in their beds by young rich beautiful wives?”

“Old wives can poison too, New Father.” I answered. The old man, Pantan, laughed. But Mam squeezed my forearm tightly and an exhalation, like the startled breathing of a bison, flew out of Ydalle’s mouth.

Taer turned to Ydalle and, lips in a conspiratorial smile, and took her hand gently. “Ydalle,” he said, “you’re a good soul, but don’t worry so much. Satha and I understand each other.” He turned to me again, smiling. His smile honored me greatly, because the Doreni never smile at strangers. “Daughter, it was because your father was so honorable that he lost all his fortune. No one else stayed to feed the poor after the Angleni salted the fields. I can trust my son to the daughter of a poor and honorable man who gave all in his store to feed those who could not repay him.”

“New Father,” I answered, “I’m relieved you explained this to me. I was beginning to fear, with such talk of cold cruel hearts, you didn’t like women very much and that you had chosen me because—”

A sound like that of an eel slipping out of a woman’s hand issued from the mouth of the lavishly dressed woman and silenced me.

“I like women well,” Taer answered, looking briefly in the woman’s direction. “And I find—now that I have spoken to you—that I like you very much.” He again glanced at the woman who seemed to have made herself my enemy. “Women who speak their minds don’t betray their husbands. Only, only, be gentle with my boy. He’s young yet and hasn’t enough experience to challenge your wit.”

He smiled again, and perhaps I saw too much in it. Perhaps it was only a fatherly gesture, but it troubled me, for already my eyes and heart were finding him too pleasing.

“May I ask you one more question, New Father?” I asked. Behind me, Mam was shaking like a volcano about to release its fury. “Do you truly want a wife for your son? Are you sure you haven’t brought me here to be his mother?”

Taer did not hesitate in his response. “Loic has many mothers, New Daughter. He doesn’t need another. A guardian of his heart, though—someone who will allow his heart to rest in her bosom—would do nicely.”

Many mothers. Orphaned children abounded in our land in those days, and my heart melted at the words. How sad, I thought, to have the falling sickness and to be motherless at the same time!

A din sounded in the mirrored hallway. All the guests stood up and I, too, prepared to stand. But Mam’s hand pushed me back into the pillow. Soon the thin slats of the ebonywood curtains seemed to fold themselves away, and behind them—as if rising up from an unseen realm—was the willful eighteen-year-old who had changed my life. On either side of him near the mosaic-tiled walls, singing servant girls played on tambourines. Leading him was an old woman whose braided white hair flowed out from under a Doreni coif. She wore the cotton leggings of a mamya under a buckskin tunic, and he kept glancing back at her as if asking for her approval. Her response was always a doting smile. She led him toward us as if he were Our Matchless Prince himself.

I should have been happy to marry the son of a great chieftain. Indeed, he was good to look at, nicely proportioned with thick hair tumbling over his shoulders like the waves of a waterfall, not like the little baby I half-remembered. He wore a green clan-cap made of dyed deerskin, with the Pagatsu beadwork. However, no feather or ribbon hung from the two golden loops in his earlobes. The only signs he was a chieftain’s son were the flowing embroidered sleeves of his long buckskin gyuilta and the jade Doreni firstborn bracelet.

He walked toward me, and when he arrived at my side, he turned his eyes on me. How silent the room became as he stood there attempting to peer behind my veil. Pale eyes he had, strange eyes, which seemed to mirror everything they looked at. For as they roamed my brown skin, brown they became, and when they rambled over the neckline of my green dress, a forest glade rose in them. Yes, he was good to look at. Except that his nose was a little too long, and one tooth was broken. A dull brown bruise near his chin, and a scar running the length of his forearm made me remember his illness. I thought, I’ve married a boy so doted on and spoiled he’ll probably end up even more useless than Father. No, he doesn’t seem like someone destined to be a warrior at all.

The moment this thought entered my mind, a hurt look appeared on his face. Surprised, I glanced at Mam. She shot me a threatening glance. I remembered her warning and her fear of ending up on the streets. My eyes stung. But how could I cry when the wounded eyes of a Doreni warrior’s son were trying to peer into my soul?