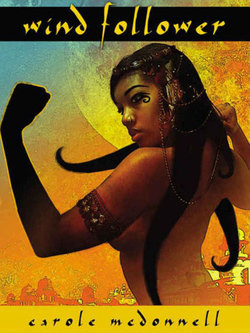

Читать книгу Wind Follower - Carole McDonnell - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLOIC: Encounter

As I walked to the sword trader’s shop, a man dressed in a shaman’s vest walked past me. He eyed me suspiciously, glowering, as if the spirits had told him some harsh thing about me. As he passed by, I suddenly remembered that all swords were dedicated to one spirit or another. Instantly I resolved not to buy a sword at all, but rather to make one. In that way, no spirits could enter it and I would not be forced into a league with them.

I told my father my intention, but not the reason for it.

He said, “You want to make your own sword? You have no skill in sword-making, and the new swords imported from Ibeniland have such power, grace and—”

“No, Father,” I said. “I shall make my own sword.”

“How strange your whims have become since Krika...”

I shook my head, hinting he should not speak another word.

He stared at me in silence for as long as it takes for a hawk to wing across the sky. At last, he said, “It is I who should tell you when not to speak. Not you who should tell me.”

“Why do you insist on speaking about Krika when I do not wish his name to fall from your lips? And don’t call my desires ‘whims!’ Don’t presume to think you know my soul so well that you can judge my desires!”

“I knew your soul once,” he said wistfully, “and what I didn’t know you told me.”

“’Once’ is a time and times ago. ‘Once’ no longer exists for me.” I pointed at the blacksmith’s shop. “As for the sword, will you allow the comrades in our armory to help me make it or not?”

He turned his face toward the ground. Since Krika’s death, he had tried often to rekindle our old closeness. I understood his heart, yet I could not forgive him. I chided myself for this because in most matters he was so good a father. Thinking to make the mood between us lighter, yet not wanting to actually apologize, I said, “King Jaguar will smile when he sees the sword I’ll make.”

Laughter was always ready on Father’s lips. “He’ll smile when it breaks in your hand. But go ahead. Buy what advice you can from the blacksmith.”

In those days, I often knew the thoughts of those around me and I suddenly saw his thoughts. An eighteen-year-old boy who is petted and worshiped by all the women of his clan: why should he listen to an old man of forty-five? How can he understand that his father is powerless against the spirits?

It was not “thought-reading” as the Angleni called it. Nor was some demon responsible for it. Knowing another’s thoughts seemed nothing more than a natural extension of understanding and insight. What else could Father have been thinking?

When I returned from the blacksmith’s shop, he was speaking with a horse dealer. Collecting and breeding horses had become his chief occupation since the war ended. Yes, let me praise my father! He was noble and good and his victories helped stall many Angleni invasions. His vialka broke the backs of many an Angleni general.

He stood examining the back of a painted stallion with red, black, and bay coloring that mirrored the sunset.

When he saw me, he pointed in the direction of two Theseni women some forty paces away near the tent of a seller of exotic vegetables. “The one in the half-veil reminds me of Monua,” he said. “The one who lies in the bosom of my old friend Nwaha. She has Monua’s fierce stride. A walk I can never forget.”

“Perhaps fate has conspired to bring two old friends together again,” I said, walking to his side.

“If that is indeed Monua, the other woman—the one in the virgin’s full veil—might be her daughter.”

He looked past the wagon masters, past the fabric merchants, past the makers of candles and the carvers of wood. “Nwaha should be nearby. Yet I see him nowhere.”

“Perhaps your friend is dead, Father. Friends die. Didn’t you say he lingered in the old region long after the other townsmen had fled? Didn’t the Angleni kill most of the men in the Kluna clan?”

Sorrow swept across his face. “Yes, because of their dark skin. The Angleni killed the Kluna, rather than imprison or enslave them as they did the Ibeni and our people.” He wiped a tear from his face. “How I loved my youth spent among the Kluna! How sad it is to think so lovely and kind and good a people are now gone from the world!”

Seeing his grief, I regretted the words I had spoken earlier. “Father, take heart. Look. She doesn’t wear the widow’s fringe. Perhaps your friend is yet alive.”

“What did the blacksmith say?” He asked, his mind obviously on the women.

“That his son could bring all the steel and skill I need to our Golden House.”

“He can teach you, this blacksmith’s son? How old is he? About Krika’s age?”

“He’soldenough,”Isnapped,annoyedthatonceagainhehadmentioned Krika. Feeling immediately ashamed, I tugged on his braid, which was so long it reached his waist. “Father, if you’re going to stare at the women, you might as well speak to them. But be sure that the woman is indeed your old friend, or be prepared to receive a hard slap for your mistake.”

He grinned, and gave me a sidelong glance. “Since when did you become an expert on Theseni women?”

“My aunts have told me that Theseni women don’t like strangers speaking to them on the street, as Ibeni women do. Nor are they as joyous or free-thinking as our Doreni women.”

He grinned. “They have taught you well. Nevertheless, it is time, perhaps, that men and not your aunts or your Little Mother teach you about women.”

“True, I’m smothered daily by women. Yet, it is a good way to learn their habits, don’t you think so?”

He took a deep but determined breath and glanced at the women. “Perhaps. But come now. Let’s see if my face gets slapped.” He raised his right hand and signaled the women.

With that small signal, my life changed.

When the older woman turned to look at us, she nudged the younger one, but the younger one seemed to lack all etiquette and all sense of daughterly submissiveness. She turned, took a brief glimpse at us, then walked in the other direction towards the booksellers’ tent. The older woman tugged at the young one’s sleeve, but in vain. The young one merely hastened her steps.

Intrigued, I watched her. Her refusal to follow her mother spoke of a fierce beautiful will. Perhaps, I thought, it is this very independence of mind that causes her to wear plain sandals instead of the fashionable shoes Satilo women wear but are always complaining about.

A wind came from nowhere and blew her veil sideways, revealing her face. Although she was some distance away, I could see how beautiful she was. Then another wind blew—yes, although the day had been as still as summer clouds—and that gust threw her gyuilta from her shoulders, causing me to see how closely her simple cotton kaba hugged her svelte figure.

In the old days, before the Angleni forced their own customs and dress upon us, all tribes and both sexes wore the gyuilta. An unmarried girl could make a gyuilta sing. Whether it was a long one with elaborate fringes and beadwork, or a short one for riding; whether silk, linen, cotton, wool, buckskin, leather, or lowly hemp; whether worn as a scarf to protect against the sand, or as a shawl to shield the face from snow—how that cloak could turn men’s gazes!

I must have been handsome in my younger days. Or perhaps it was merely my father’s wealth. For many, many girls—oh, girls without number—would let their gyuiltas fall from their shoulders as I passed, allowing them to trail along the ground for me to retrieve. Such flirtations fascinated me, but my heart never leapt for any of those girls, pretty though they were. No, not until I saw Monua’s daughter did my heart leap. As an Ibeni poet has said, “My heart leaped then, for love had leaped into my eyes.” It was my first taste of love, and after such a small sip I was intoxicated, speechless, wanting nothing more but to devour her.

Father had noticed the girl’s behavior too, for he said, “The young one must be her daughter. They share the same fierce walk.”

“But the daughter’s is gentler,” I said. “Less aggressive. She has a better figure too. Thin in the right places. Round in the right places.”

Father’s turned to me and squinted. He laughed and the laughter momentarily softened the sword scar along his left cheek. “Son, you’ve found your good mood again. This pleases me. To know how to forget past griefs is to move from childhood to—”

“I’m eighteen, Father,” I said, firmly cutting him off. “I’ve moved past childhood. Or others have pushed me past it.”

“Your anger is misplaced, Loic,” he said, raising his voice. “Okiak killed Krika, not me. For the past year, you’ve made yourself my enemy and I suggest you study what it means to have an enemy before—”

“I have not made myself your enemy, Father.” I pointed to the approaching woman as another means of silencing him. “No, that was none of my doing.”

As the woman was only footsteps away, we put our disagreement away.

She soon stood in front of us, making a great show of studying our faces, craning her neck this way and that. A smile flashed across her face and she bent her head low. “Taer!” she shouted, her voice much too loud. “Is it really you?” Tears streamed down her face. “Has the Good Maker given my Nwaha such joy by causing me to cross paths with his old friend?”

Her joy seemed sincere enough, but I suspected this was no “accidental” meeting, that the woman had planned it somehow. Yet, her deception didn’t trouble me. Quite the opposite; for reasons I little understood then, my heart was glad of it.

The flesh on her bony arm sagged as she pointed at me. “So, First Captain of King Jaguar’s armies, is this one of your sons? Loic, is it? Your oldest boy?”

I nodded, clasped both my hands together and bowed to her. “This is a day the Creator made,” I said, giving her the customary greeting.

“It has certainly brought blessings,” she answered. “How tall and handsome you’ve become, Loic tyu Taer! You have your mother’s light eyes! You’re thin, though.” She tapped my stomach. “The son of a rich man should have more flesh on his bones. I don’t know if your father told you, but my precious daughter used to hold you in her arms. Yes, you were her favorite little doll those rare times she saw you. How she used to laugh when you crawled between her feet without so much as a breechcloth!”

“Was that the girl who stood beside you?” Father asked, sparing me further embarrassment.

“Yes, she is the joy of my life. If she had known it was her dear father’s dear friend who called me, she would not have left so abruptly. Unfortunately, she had an errand to attend to.”

She lowered her eyes and I saw that she was flirting with my father. “I’ve heard much about the exploits of the First Captain of King Jaguar’s armies, the Captain of all the armies of the three tribes! How could we not hear? Oh, and I’ve seen your beautiful wife many times in the marketplace, walking with your younger son. Unfortunately, I don’t know your other little one’s name.”

Father’s eyes widened. “You saw my servants and my wife, and you didn’t approach them to send me a message?”

She bent her head low. “Who am I that I should push myself into your life? No, Nwaha and I are unimportant people now. But enough about me. Your wife is a beauty, Taer. But—” she clicked her tongue “—only one wife?”

Father nodded.

“You’re being stingy with yourself, Treads Lightly. Most rich men spread themselves around. They don’t tread lightly when taking earthly joys. But I’m glad to see you’re well, my friend. We’ve often asked the ancestors to protect you.”

The poor are allowed their scheming, I suppose. Especially the poor who once were wealthy. I would have liked the woman better if she hadn’t chattered so much.

Father bowed his head. “I’ve prayed for your family also.”

“Waihai!” she said, “The Good Maker obviously heard our prayers, but not yours.” She followed this with a laugh so obviously meant to call the market’s attention to the fact she was speaking to the King’s Captain that if I hadn’t wanted to meet her daughter, I might have found an excuse to leave.

Father was always patient with deceptions, however. Or perhaps he was more gracious about them. Or maybe he simply didn’t recognize them as often as I did. He said to her, “Give my prayers some credit for your health and happiness.”

“You don’t want credit for something so small and puny, my friend.” Her conniving was relentless.

Wishing to stop it, I asked, “But where is Nwaha? He’s wrong not to have told Father you were settled in Satilo.”

“Your father knows how proud Nwaha is.” She pointed across the marketplace, to the other side of the Sun Fountain where a tattered banner blew before an equally tattered tent. “That’s our home. Our shop.”

Father began walking towards the shop but—she reminded me of actresses I saw once in King Jaguar’s palace—she stopped him, bending low and clutching at her chest. “Don’t dishonor us, my friend, by coming into our house. The shame would be too great. I would be doubly shamed to serve a guest the poor food we have.”

“To hold my friend in my heart and eyes is all the sweetness I need,” Father answered.

That was a common phrase in the old days, intended to free the poor from the oppression of the hospitality laws, and for a moment, I feared the old woman had overplayed her hand. If, out of respect for his friend, father declined to enter Nwaha’s house I would be deprived of seeing the girl.

Monua, perhaps suspecting she had played her role too well, lowered her head to the side. Then, crooking her hand, she said, “But if you do not mind poor fare, come and see. I know you’re kind and will not be disgusted at our lowly position.”

Waihai! My heart leaped! It seemed full of a most profound happiness. I must have been smiling like a fool, for Father gave me a questioning look and gently touched the tiny hairs sprouting on my lip. Perhaps he only smiled at his own happiness at being suddenly reunited with his old friend. Whatever the reason, we both were in good spirits.

Our smiles faded when we entered Nwaha’s three-room shop. When I was a young child, my Little Mother taught me an alphabet song:

“If ever you enter a house and find it dirty, dingy or disarrayed,

Don’t judge the dwellers of that domain.

For a dirty, disarrayed, and dingy house

Declares its owners are poor, ill, tired, or grieving.

Dinginess doesn’t imply defect or dereliction.

Dirty houses do not display dirty hearts.

Decisions decided on disarray should be disregarded.

Your heart would itself be dirty and disarrayed

To determine another’s worth on such dealings.”

I remembered the little song and restrained my mind from harsh judgment.

The public front room, where Nwaha worked his trade as a tent-maker and where Monua made and sewed dresses, was the most presentable, even though its buckskin walls were crumbling away. I didn’t see the inner room where their daughter slept or the third room, which was Nwaha’s and Monua’s, but the scattered fabric remnants and the abundance of scavenged sundries in first room hinted the unseen rooms hid overwhelming poverty.

Nwaha directed Father to a rickety wooden stool. His tightly curled black hair was turbaned in the northern Theseni style despite the heat of the day. Although he was about Father’s age, wrinkles lined his face, making him seem older. “My eyes rejoice to see you,” he said. “What victories you’ve had, Treads Lightly! Your name rings out in many war songs.”

“When you hear them, don’t sing along with them,” Father said, sitting down. “Those victories have cost me deep defeats.”

“Even so, I’m as proud of your successes as if they were mine.”

“They are yours, Nwaha,” Father answered. “I could not have won a quarter of my victories if your spirit had not sustained me.”

“So you are Father’s childhood friend?” I asked, although as a youth I should have stayed silent in the presence of an older man. “So we meet again? And this time, I’m wearing a breechcloth.”

He laughed, and his teeth gleamed white against his dark brown skin.

“But tell me, Nwaha,” I began, “is there anything you need?”

Father gave me a reproving look. I silenced myself immediately, realizing to ask such a question was a breach of etiquette that would only shame Nwaha.

However, Monua leaped at the opportunity despite the embarrassment spreading across Nwaha’s face. She deftly avoided Nwaha’s extended left hand as he tried to prevent her from speaking. “Your father’s generosity is known throughout the region,” she continued. “And it seems his son shares that same generous nature. But let us not burden your father with our misfortunes.”

“How could you burden me, Nwaha?” Father asked. Preserving the honor of another was an art. Father turned to me. “Son, the talk of two old men will not interest you. You know how your Mamya worries when we return late. She dotes too much on her little charge. Now, don’t give her any cause to worry. Ride straight home.” Yes, he wanted to pay Nwaha’s debts, but speaking of such matters in front of me would have been an etiquette breach. That was how things were done in the old days. Subtly, tactfully.

Yet, I wanted one more glimpse of Monua’s daughter. “Permit me, Father,” I said, “to go to the horse dealer? You wanted the painted stallion, didn’t you? The one who looks like a sunset during the cold moons. Shall I buy him?”

“Bargain well,” he answered. “Don’t let that cheater take advantage of your youth. Instead of riding Cactus home, ride that one. Study how he behaves and tell me all your observations.”

I immediately got up and raced out the door. When outside, I searched the arcs and walkways of the marketplace until I saw Monua’s daughter. I found her at last, a long way from Nwaha’s shop, near the Sun Fountain. She held a water jug in her hand. I hurriedly paid for the stallion after bargaining only enough to assure a fair price, then followed her as she approached two Ibeni beggars sitting beside a hemp plant. The men’s faces were tattooed, a sign they had committed treason against the king—probably some conspiracy with the Angleni. None in the marketplace offered them quixa, water, or food. None but Monua’s daughter.

I watched to see if she exchanged any words with the beggars. She did not. In those days, an unmarried Theseni woman could not speak to a strange man, but taboos could be worked around. Kneeling beside them, she put fruit and bread in their hands. These they ate greedily and humbly. She fed them then, unspeaking, hurried away. No one in the marketplace reproved her for this, which I considered strange and wonderful indeed. I smiled, seeing her kind, brave heart; seeing it, I loved her more. Kindness combined with courage is a rare combination, I said to myself. Such a wife does not shame or harm her husband, and she is like a warrior by his side.

Darkness lay over everything like the gentle stroke of a woman’s comforting hand. I wondered whether the Wind had sent me one to lie in my bosom, or if—as Father had been saying—grief for Krika had made me whimsical. Even Little Mother, who always gave and forgave me everything, had begun to say I was impetuous. The sun had already rolled away into the far horizon and the vendors were busily packing up their wares. Some had already closed the curtains of their tents. Because the Doreni horse dealer was still present, I decided to open my heart to him.

“Older Brother,” I said, greeting him. “This was a day the Creator made.”

“It brought many blessings,” he answered. “And that horse is one of them. You got a good bargain, there.”

“Tell me, Older Brother, if you know ... what kind of girl is Monua’s daughter?”

He glared back at me, his eyes suddenly angry under his clan-cap. “You mean Satha?”

“Is that her name? Satha?”

You who have forgotten the old language cannot understand the joy with which I received her name. You hear our names, you hear the names of people in my narrative and those names mean nothing to you. But before the Angleni destroyed our language, blowing it away as one blew away chaff in the wind, names meant something. “Satha” was a Theseni word which meant “Queen” or, more accurately, “Queenie.” It sounded like the Doreni word, “Sithye” which meant “dawn,” a name close in meaning to mine.

“Satha,” I repeated. “It is a lovely name.”

“Aren’t there enough women in your father’s compound—captive slave girls, servants—you can misuse?” He pointed at the jade bracelet on my right hand that signaled that I was my father’s primary heir and the future chieftain of the Pagatsu clan. “Shame on you, Loic tyu Taer.” His eyes were like unsheathed daggers, his tone sharp like knives.

In those days every Doreni clan was at odds with every other, and his angry eyes made me wonder if some grudge lay between my clan and his own. I was glad the bracelet gave warning that those who killed a first-born would bring vendettas and clan wars upon their head. “I don’t recognize your clan cap, Older Brother,” I said. “Is there some fire between your clan and the Pagatsu?”

“It isn’t your clan that bothers me.”

“Then what fire is there between us?”

“Like a true Doreni, I am a brother to all people. But your rude intentions towards Satha nauseate me. Can you not call any of your slave women to your bed? For all I know, you and your father probably share the same woman despite the taboo. That’s the way you rich people are, flaunting the laws. Although you have a herd of women from which you can choose, you want to take a poor man’s one little ewe.” I watched nervously as his agitated fingers groped about the horseshoes and horseshoe nails on his stand. The knife he suddenly lifted before my eyes glinted in the moonlight.

It was true the Doreni sought to be brothers to all men. Before the Angleni came and colored our perceptions of each other, marriages and love affairs between the different tribes were frequent, but weddings between rich and poor were less common. Although a rich tribe could bring wealth, status, and protection to a poorer tribe, what could a poor tribe give? It was also true that in the Golden House many servant girls and some of my female cousins had shown their desire to couch with me. Although, from what my Little Mother told me, they were more desirous of replacing my father’s hated third wife than they were of lying in my hairless bosom.

I pushed the knife away, feeling strangely pleased that my tribesman had defended Satha so vehemently. “Satha tya Monua has nothing to fear from me.”

His eyes searched mine, the threat still in them. “Are you being honest?”

“Very honest, Older Brother.”

He bent towards me and managed a conciliatory smile. “Well ... as long as you mean the girl no harm. She’s a good girl, that one. Proper. I wanted to marry her myself. But she has no dowry. And, as you can see—” he gestured towards the back of his tent “—I’m a poor man. She’s industrious, don’t misunderstand me. But when one considers a wife—even if the girl has noble ancestors—one might as well get more than a few quixas to take her off her parents’ hands.”

“Poor men can’t marry poor women,” I cited a proverb my Little Mother had told me. I didn’t add the end of the proverb however: “Rich men, therefore, have a greater selection.”

“Good luck with the girl,” he added as he pulled the slatted curtains of his shop together. “And remember me if you wish to buy another horse. Don’t tell your father about ... this little incident between us. I wouldn’t want him thinking I tried to murder his son.”

“I assure you, Father has met many who wanted to murder me.”

He nodded knowingly, “It is always that way with rich men’s sons.”

I tied the stallion—whom I now called Sunset—to Cactus and to father’s horse. How like brothers they looked with their similar sunset coloring, and how like brothers they behaved, nudging each other with their noses. They whinnied as if resuming an old conversation.

I walked to the next vendor. “A lovely day the Creator made, is it not?”

The Ibeni merchant stopped packing away his wares and turned to me. “It brought many blessings.”

“The greatest of which was that I met Satha tya Monua and jobara, indeed, she is a beauty.”

A lascivious smirk came to his lips. Yes, that one was typical of his tribe—suspicious, lustful, and jealous; hexes, fetishes, and carved idols guarded his shop. He wore the typical Ibeni patchwork leather vest—embroidered spells and chants decorated it but I didn’t recognize its clan markings. A Doreni woman in an Ibeni veil appeared behind him but he jealously hurried her away. She fled immediately and I found myself wondering why a Doreni woman—for our women are bold and shrewd—would marry an Ibeni man.

“Yes, Little Doreni,” he said after the woman had scurried behind the slatted curtains. “Monua’s daughter is a beauty. Even with the veil, one can tell. But she’s not one to lay in the fields with a boy, if that’s what you’re after.” He lowered his voice. “Or with a man either. Believe me, Little Doreni, I’ve tried. Waihai! Who would know? I offered her one thousand quixas for the romp—a lot considering an Ibeni woman could give me far more for far less—but I couldn’t convince her. The Uncaused Causer of all things knows her family needs the money.”

It is difficult to turn the mind of an Ibeni away from lustful imaginations, but I tried, whistling at his generosity. “A lot of money, that.”

“Enough to feed even your household for a month, little rich Doreni.” He bent towards me, fingering the porcelain frog fetish dangling from his neck. “I would have married her and made her my ninth wife if she had agreed to play with me.” His hands carved a female figure in the air. “That torn-up oversized gyuilta she wears over her kaba can’t hide everything, if you know what I mean.”

“I think I do.” Nine wives. But that was also typical of the richer Ibeni. Their eyes liked whatever they saw, and what they liked they had to have.

“So you want her?”

“I think I do.”

He sucked at his teeth. “Good luck! You’re Pagatsu, right? That’s what those clan markings on your clan cap say?” He too glanced at the jade firstborn bracelet. “You’re a chieftain’s son?” Knowing the Ibeni love of status and power, I didn’t immediately answer. “Come now, little rich Doreni. I know a few things about clan markings and I heard Monua earlier.”

“True, I am Pagatsu.”

“Taer’s son?”

I nodded.

“You’re from a noble clan. Unfortunately, that won’t win her over. Now, if you were from the Therpa Doreni, let’s say. Or the Trabu Theseni like Queen Butterfly, then ... perhaps you’d feel no qualms about taking her. After you had her, you could discard her or do with her as you wish. You wouldn’t be stuck with her after your lust had cooled, as often happens.” If I had fallen into the sewage pit on the outskirts of town, I couldn’t have felt dirtier. “How old are you anyway? Fifteen? Sixteen?”

“Old enough.”

“Rich enough is more like it. Led by your heart, are you? Believe in a ‘destined one’ probably?” He chuckled. “Alibayeh! Marry her, then. You might as well start your household now. One young man I know—not Doreni, but very rich—already has four wives.”

A Theseni vendor near us interrupted him. A good thing, too, for my anger was already kindled against the Ibeni. “I’ve been listening to your conversation.” He unwrapped his long cotton turban, and scratched his nearly bald skull. “But you’ve picked the wrong one there. That one is too virtuous to be any fun. And bookish. She’s always in the bookseller’s shop, looking for writings by the old scribes. That’s why she wears that old gyuilta, so men won’t take a second look. She doesn’t want to marry at all. Sometimes I seeher in the cool of the evening, after she’s finished her chores, reading. On holy days, she visits the houses of the poor, the old, and the blind, and she reads to them.” He grew suddenly silent, and his eyes seemed to be looking at some inner memory. I suddenly knew—in the way I knew many things—he was thinking of his old days. “But few saints have such a body, one obviously made for sin. Try to woo her if you can, but perhaps it’s best she grow old unmarried. Who wants a holy one in his bed?”

We Doreni were generally tan-colored, with brown, auburn or black hair. Satha’s family, being Theseni, was a rich deep black. I wondered if he thought my mind was like his, for Theseni men judged by such matters.

Both men shared a laugh that turned my stomach. How lucky it was I had decided to make a sword instead of buying one! If the sword had been in my hand, I would have rammed them through. I choked down my anger; they were older than I. One wrong word to either and I would have faced the Council of Elders and Beloved Women as Krika had. Yes, even though I was a rich man’s son, the son of the king’s First Captain.

I walked from the marketplace towards Nwaha’s shop, and my heart ached because such words had been spoken against the girl who had found lodging in my heart. I wanted to clothe her bare arms with jeweled bracelets and give her golden nose-rings and silver anklets and, at the same time, shower her with praise and tell her how beautiful and how good and worthy she was. My heart reasoned that if I bathed her with worshipful love all the snide judgments poured on her would fall like broken chains about her ankles.

Near Nwaha’s house, I saw her in the garden, pulling ground tubers.

How, I asked myself, will I make Monua’s daughter speak with me? I was Doreni, I reasoned; I didn’t have to follow Theseni etiquette. Moreover, the law of hospitality triumphed over all customs, as mercy often triumphed over justice. The thought occurred to me that I lived on the edge of the city and could be deemed a stranger. I, therefore, had the right to ask even an unmarried Theseni woman for water from her well.

“Satha! Tya Monua!” I called out.

She looked up in the direction of my voice.

The other vendors had closed their shops and no one would have seen her if she had spoken to me. But she didn’t walk toward me. She returned to her work pulling tubers in the dark garden.

I called again. “Satha, are you so aloof you won’t talk to the son of your father’s friend?”

Again she looked. This time directly at me; again, she didn’t approach me. I regretted my casual clothing. Only a tunic, deerskin leggings, undergarment, and breechcloth. Nothing to show my hunting skills, no rich gyuilta, nothing to make her want me. Yet, I reasoned, would I want a girl who accepted me only because I was dressed richly?

What did Sicma the great Ibeni poet say of Queen White Star? “Her beauty illumines the face of all who see her, and in the gates of the city all women shine through her glory.” But not for me Queen White Star. Not for me the flamboyant First Queen Butterfly, not for me the gentle Doreni Queen Sweet-as-Jasmine. None were as beautiful as the daughter of Monua. No, none of the three wives of King Jaguar, or any of his eleven daughters could match the girl’s beauty, regal bearing and exquisite willfulness.

Her refusal to speak only made me want her more, but before I could call out to her again Father exited the shop.

“Loic?” He raised his hands questioningly. “Why are you harassing Monua’s daughter? She’s not your servant. I thought you had ridden home.”

I pointed at the door to Nwaha’s shop and gestured to Father to follow me inside.

When I stood in front of Nwaha, I said, “Father, Monua’s daughter pleases me well. Get her for me to wife.”

My father’s eyes narrowed in surprise, then closed and opened again, angry. But Nwaha said nothing, did nothing. It was Monua who acted. She stood up in such haste the bamboo stool on which she sat fell to the ground. A second later, her hand was gripping the long shaft of a vialka. Jobara! That lance was indeed a graceful weapon. The Angleni have now outlawed it, but Layo, layo—truly, truly—how sharp and graceful that weapon was!

She pointed it at my throat and shouted at my father. “Treads Lightly, have you and this son of yours come here to mock our poverty?”

I had not thought that my sudden request would be considered an insult, but the vialka’s blunted edge skating across my flesh—and pressing deep enough to cut—made me realize otherwise.

“I know full well that my daughter is dark and past marriageable age,” Monua said. “Unattractive she may be, but I’ll not allow the son of a rich man to use her as if she were a slave.”

Such a defense of her daughter! More insult than praise, such a champion no woman needs. The anger the vendors had kindled within me still burned and when I heard Monua’s words, it burned hotter. Heldek and Pantan had trained the young princes and the dukes as well as me in warfare. Embarrassed though I was that a woman was pushing a vialka into my throat, and able as I was to turn it away, doing so meant insubordination toward an elder. I grasped the vialka’s tip with my palm, but restrained myself from turning it on my hostess.

All the while Nwaha continued sitting there, weak and pitiful. Father kept glaring at me, as if I—and not Monua—was in the wrong. How, I thought, can Nwaha sit there and let his wife fight his battles? Even battles she had created in her own mind? How can Father endure a friend such as this?

When it seemed my neck was about to break from being long held in such an uncomfortable and dangerous position, Father placed his hand on the lance and gently pushed its tip downward. “Loic meant no disrespect, Nwaha,” he said. “He’s young and easily tossed by the wind’s whims. Even so, all in the city of Satilo, all in the Jefra region, and the outlying suburbs of Rega know him to be an honorable youth.”

How surprised my heart was that Father defended me!

“His name means ‘Full of Light’,” he continued. “And he is. If he says he wants to marry your daughter, she has found a place in his heart. He’ll treat her well and honor her always as the gatekeeper of his heart.”

“As some second-status wife to cover his thighs!” Monua shouted, glowering at me.

Again, Father defended me. “Not so, Monua,” he said. “Do not insult my son.”

“Should I give my beloved Satha to one who has no manners?” she asked. No, she wasn’t one to keep her mouth shut. “Do you want the joy of my life to spend heartbroken nights lying in the women’s quarters listening to her husband tumble with other more-beloved wives?” She was a blunt one!

Father answered, “I promise he will marry only one wife, whatever good or evil comes.”

In those days, a father’s promise would bind his son forever. To break such a promise was to invite death and grief. His insulted soul would return from the dead to haunt or kill the disrespectful child. Yet, his promise seemed a blessing to me. I could not imagine holding any other woman in my bosom.

Monua’s suspicious eyes continued staring at me. “How could he want someone he’s only just met?” she asked.

I saw her mind then, saw that she was like one standing in the middle of a bridge, not knowing whether to go forward or step back. I searched my heart for the right words to help her cross that bridge.

About that time, her husband found his mouth. “Satha is already twenty-four, my friend. Wouldn’t your son rather marry some little girl his age, someone he can grow old with, rather than a woman of unmarriageable age? Consider too that Satha is not of his tribe. Nor is she rich. What can we give you for such—?”

“I don’t want some little girl,” I shouted, rubbing my neck. Now that I was free from any threat of Monua’s weapon I, too, found my mouth. “I want Satha.”

“And you rich boys always get what you want, don’t you?” Monua said, her eyes scorning me. I saw some ugly thing in her soul, and feared the prospect of such a “New Mother.” What if Satha tya Monua turned out to be a “true daughter of her mother?”

Yet, I ached to free Satha from her parents, yearned to caress her in my bed. Already she had begun to fill my future. In my mind, no future event excluded her. No feast, no journey, no riverwalk. How could I live without her if she had so enmeshed herself into my future life?

“A child who receives all he wishes is not a true son,” I said to Monua. “I am Taer’s true son, the hope of his old age, the honor of my dead mother. Just as Satha is the honor of her mother. I do not waste my time on foolish wishes as others do.”

“Mentura—untried boasting,” she answered, as if she, a woman, were a warrior or a man my equal. “Your son makes speeches to his elders?”

“Perhaps you should not insult someone you hardly know!” I snapped back. Yes, I did this, even though we were guests in her house. Father lifted his left hand, as if to strike me.

He had struck me only once before, on the day I told him I intended to kill Okiak. Seeing his raised hand again, I feared he would not allow Satha to marry me. Terrified at losing what I had not yet won, I clasped my hands together, and knelt on the floor pleading, “Father, forgive me. I spoke rashly.”

Monua shook her head several times. “You’re lucky you did this in our house. If the elders knew of this.... “Her voice faded with the vague threat. “Before the war, children would have been stoned for less. But the war has made us all tired of bloodshed. The poor have always had to suffer humiliations. Never did I dream I would become one of them.” I sensed that three thousand quixas would have suited her “humiliation” quite nicely.

“Your son’s mind is mad with love,” Nwaha apologized for me. “Young men are rash when they’re infatuated.”

His words caused his wife’s wrath to turn toward him. She removed her wifely half-veil before us and wiped her eyes. “The boy insulted you and here you are wiping his bottom with that weak tongue of yours. Have you no spine? No, I have no husband. Not one worthy of the name.”

She retreated through the wooden curtains into a far part of the house. But even hidden from us, she wailed loud enough. Doves in the Eastern Desert could have heard her sobbing. “What a fool I was to marry such a foolish man!”

Nwaha held up his hand. “I frustrate my wife, as you can see.” He lowered his head and pushed his dark brown fingers through his hair. “Taer, my friend, you see how it is. Who would have thought that those we love would mar our reunion? Forgive me if I sin against courtesy and ask you to leave, but you will understand that so much shame in one day is more than—”

“Our reunion is not marred,” Father said. “Are we not covenant brothers? There is no sorrow or shame, which we cannot endure together. Now, if you honor me, you must allow my son to marry your daughter.”

“I’ve met many rich men in the fifteen years we have been apart. None but you, Taer, have honored the poor. Jobara! Indeed, I’ve chosen my friends well.” He turned to me. “Loic, with a father so honorable, I have no doubt you too are a man of great honor. Forgive me for insulting you. But think about it, lad. You are but—”

“Eighteen and old enough.”

Father gave me a quick angry look, then spoke to Nwaha. “Isn’t this a surprising thing?” he asked. “My friend, do you not remember our old promise?”

Nwaha squinted, apparently confused. “What old promise, my friend?”

“That our children would marry,” Father said, smiling in pretend amazement.

It was the first time I had ever heard of such a promise. I knew immediately that this was one of Father’s diplomatic ploys. I kept my head low, my hands clasped, my knees to the ground. “How the fates conspire to bring two covenant brothers together!” Father added.

“Ibye, ibye!” Nwaha said. “Now I remember it!” Yes, Nwaha was as good a diplomat as my father was. “But those promises were made when we were both young and wealthy. Many years have passed and our feet have walked long in different paths.”

“Troubles come no matter how well we plan,” Father answered. “But the nature of the world is to bring our old promises before our eyes.” He raised his right hand towards me, and I stood up. “My friend, let our children marry as we promised each other so long ago. Forgive my son’s outburst. Love has its own rules, and a boy’s love is often brazen. Nevertheless, the love of one’s youth always abides. My first wife, though dead, is ever on my mind. I pray you then, let the boy marry Satha. If he doesn’t get his way, it will not go well with me. Loic is strong-willed and will spend all his days hating me—and perhaps you—for refusing him the girl. We would not want that, would we?”

“Waihai,” Monua said, wiping her face and returning to the room. “Yes, Taer, children are often like that. They forgive nothing and will hold it over their parents’ heads until the day we die. Some even avenge themselves against their elders when they’re full-grown. What is this world coming to?”

Nwaha gestured me to a stool opposite him. “So you think you love my daughter?”

“The Wind turned my eyes towards her, and I can see nothing else until she turns her own eyes on me.”

“Very poetic, young man,” Nwaha said. “But is there a more earthly reason perhaps for your love for my daughter?”

I smiled, feeling a blush across my cheek. “Although Satha wears the Theseni scarfed full veil I can see she is beautiful. And the shape of her body pleases me. I’ve spoken with vendors in the marketplace and they say she’s a good woman. Is there a better woman to be the gatekeeper of my heart?”

Nwaha turned to my father, “So, your son’s ypher rules his life?”

“If my ypher rules me, old man,” I shouted, “at least it’s better than you letting your wife rule you.” I stood up, annoyed I had almost begun to like one whose weakness made him unworthy of me. The girl was safely mine. Both Nwaha and Father had opened their mouths to lie about an age-old promise and I would have been a fool not to use it. “I want the girl. Since you promised each other your children, why deny me? Especially since the One Who Holds My Breath in His Hand has brought us together to bless your old promise? Get me the girl for me to wife. Let the half-marriage gathering be tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow?” Father looked at me as if I had lost my mind. “A betrothal cannot be arranged by tomorrow.”

“In two or three days, then,” I demanded. “Enough.”

Anger, restraint and shame battled in Father’s eyes.

Nwaha’s voice trembled. “But won’t people say the half marriage was hastily planned because Satha—” He disgusted me by glancing at his wife as if he would topple to the ground without her strength.

“They will say nothing,” she assured him. “They know the purity of our Satha.”

Unable to stay any more in the presence of such a man, I walked toward the doorway of the tent. “Father,” I said, “show them Pagatsu generosity.” Then I left. If I had stayed longer, my mouth would have said something my heart would have regretted.

Outside, alone, I paced before the house, wondering what negotiations were going on. For the moment, Satha was nowhere to be seen. Soon, however, she would be mine and I would see her every day.

I knew Father would not demand a dowry. Satha was the old man’s only wealth. However, Nwaha, a good Theseni father, would demand a written contract which declared Satha would be my only wife, and I her only husband. But what of that? Father had already promised that I would treat her honorably.

When Father exited the house, I raced toward him. He walked past me, silent, as if I was an unseen spirit. I grabbed him by the right shoulder. Rage flickered in his eyes. I let go.

He took the reins of the horse I had just bought, and silently tied it to the tree beside Nwaha’s house. Then, still unspeaking, he mounted his own horse and rode away, with me riding behind him on Cactus like a leaf caught in an eddy.

Silently, we rode to the outskirts of Jefra where our Golden House lay. Nor did he speak when we dismounted at our stables. He walked past me and entered his rooms in the men’s quarters while I entered mine. I waited for him to send a servant to me, but none came. When I could bear his silence no longer, I walked to his room and spoke to him through the slatted curtained doorway.

“Father, please! Please speak to me!” I shouted.

There was a long silence.

“Father, please!”

He answered, “My son, who were you trying to impress with your great proud words?”

“I tried to impress no one, Father. I found no one worthy of impressing. I only—”

“You succeeded, then!” he shouted back. “For you impressed no one. When the girl hears of your behavior, your success in not impressing anyone will be complete.”

“It’s only—I want her so much, Father.” I put my hand on the slatted wooden curtain between us but didn’t dare push it aside. “Open to me, Father, and let me speak to you face-to-face.”

I heard him speaking, not to himself but to the ancestors. Words barely distinct, barely perceptible, I suspected he might be asking them to guide me. I waited long outside his door and then, at last, he directed his words to me. “Perhaps the first error could have been repaired in some way, but you were like a merchant, adding debt to debt. Your shameful behavior has cost me much. And it is not of quixas that I speak.”

“What about their shameful behavior?” I asked, annoyed that once again, other people seemed to matter to him more than I did. “Your friend allowed his wife to fight his battle!”

“Shut your mouth or I’ll shut it for you! You with your boasting words. You who have not killed so much as a buffalo dare speak against Nwaha? At best, you sound arrogant; at worst, you’re a fool. Do you not remember who these people are, or what they have suffered in order to help their people?” He paused and drew a breath.

I remained silent, remembering what he had told me about the Angleni atrocities in the Kluna region.

When he began speaking again, his voice had softened. “We’ve spoiled you, son. A motherless child is a sorrowful thing. Indulgence would have been wrong in any case, but the Pagatsu clan is large, and I being headman and you my only son, well ... you received too much petting. A certain amount of arrogance on your part is to be expected, but your illness and the sad fact that you’ve lived your life surrounded by too many women—aunts, female cousins, doting slave girls, captives—all of whom had duties toward you—”

“My illness has nothing to do with this, and the petting and fawning of worried women might have spoiled other boys, but not me. I am sorry if I did not behave properly toward your friends, but—”

A desert owl moaned and I heard my father’s footsteps approaching me. He pushed the slatted wooden curtains aside and stared out at the sparse bushes on the western edge of the complex, apparently searching for the owl. “The past cannot be undone and Nwaha will not nurse a grudge against you. But the girl ... who knows?” He lowered his voice, softening his tone. “Is it possible, Loicuyo, you’re confusing pity with love?”

“But, Father, do you not consider the girl beautiful?”

“I hardly saw her. Nor did you, for that matter. If I know your heart—and I think I do—your love for her is mixed with pity. Jobara! Nevertheless, haven’t you seen enough of my life to know that beauty is one thing, and love quite another? You haven’t lain with a woman yet—as far as I know—and now you want a guardian for your heart.”

My father knew me well. Indeed, I did sense some wound within the girl that echoed with some hurt within my own soul, but Father didn’t wholly comprehend that it was I who felt the need of pity and care, that I needed one who would be my true family, an ally like Krika was.

He continued, more practical about my life than he had ever been about his own. “If you had any sense, you would have hired her as a servant. Then you would have had time to woo her. But like an ypherled love-sick fool, you chose marriage.”

“I’ll want no other wife as long as I live, Father.”

“Good, for that is what you have.” He laughed, then tousled my hair. Again his voice became gentle. “Your heart is as soft as mine was once.”

“Your heart is still soft, Father.”

“But what if you’re making the same mistake I did? Will she want you? You’re a child still. Have you considered what you’ll do if she doesn’t love you? What if the year-mark arrives and the time comes for the full marriage and she decides she doesn’t want you?”

“I can make her love me. I know this. You were never able to make the Third Wife love you. She scorns those noble qualities you aspire to. That’s the difference between your choice and mine, Father. Satha has a noble heart.”

“You speak boldly about my heart, my son.”

“Only because I see what your heart should have seen ages ago.”

He squinted at me, studying my face. “Young men always think themselves strong as they try to prove an old man wrong. But that victorious look on your face won’t last long. One day, my son, you’ll understand that some victories aren’t victories at all, and some apparent weaknesses are really the true victories.”

“Gaining Satha is a true victory, Father. Nothing can make me regret that. As for you, look to yourself. Don’t judge my actions when you’re the one nursing a viper in your breast.”

Other fathers in the Pagatsu clan would have publicly scolded me for such a reply. Or they might have killed me as Okiak killed Krika. But Father only re-entered his room and closed the curtains between us. Rebuke enough.