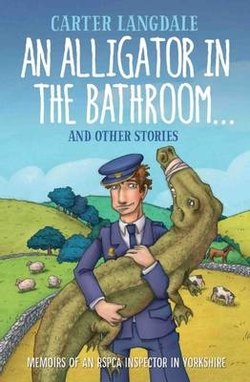

Читать книгу An Alligator in the Bathroom…And Other Stories - Carter Langdale - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE ELECTROPHANATOR AND ME

ОглавлениеAfter leaving school I had a brief dab at the navy, a sojourn chiefly remembered for the happy hours spent cleaning the bogs with a toothbrush. That was followed by half a year trying every job on every postcard pinned up at the Hull Labour Exchange. I attempted to explain to my father why it was that I appeared to be so useless. It wasn’t that I was, actually, useless; it was because I really was keen to work with animals.

‘You want to try cousin Jack,’ said my dad.

‘Cousin Jack? Who’s he?’ said I, knowing my dad’s sense of humour and so imagining that this previously unmentioned relative was perhaps a lonely goatherd living in a cave on the Lincolnshire Wolds, or someone who reared goldfish for the funfairs.

‘RSPCA, is our Jack. Has been as long as I can remember. Tell him that your mother’s mother’s sister was his wife’s brother’s wife, or something of the sort. Put that kettle on as you go.’

Quite how this information had passed me by I couldn’t explain, but cousin Jack, Jack Hartley, turned out to be an RSPCA senior figure, manager of the Hull station, and had been with the firm for thirty years. By this time he was approaching retirement with no enthusiasm for that indolent state at all. He was the big, bluff type, what you see is what you get, the sort who had respect for higher authority but no need of it and – not always visibly or obviously – would do anything to help anyone. Maybe such people still exist.

I called ‘our Jack’ from one of the special cream-painted Hull phone boxes and started to tell him about his sisters and his cousins and his aunts, but he seemed to know who I was anyway and told me to pop down and see him. Later I found out that he wasn’t a cousin at all but somebody Dad knew from the pub.

‘Now then, young Master Langdale,’ he said, after crushing my right hand into a third of its normal size, ‘sit you down and I’ll tell you what it is. The girl’s leaving to run after one of them long-haired boys that plays a banjo on the stage, and we’ve never had a lad doing it. But that doesn’t mean we won’t.’ I tried to look hopeful and expectant, rather than stupid. If I listened carefully, I thought, I might be able to divine what on earth he was on about.

‘Twenty kennels,’ he continued. ‘Sometimes up to twenty dogs, but never more. Understand?’ I nodded, hoping he wouldn’t test me. ‘If there’s no room when a new dog comes in, and we have to make room, you see, with the electrophanator, no blame can be attached to the kennel maid or, in this case, the kennel knave I suppose you are. Even so, if it was me, I’d regard it as a personal failure. Now, let’s go and have a look.’

Electro what? Cousin Jack pronounced this new word ‘electro-FANter-nor’. By the time I found out what it was, I would know it was an ee-lec-TROFFernater. Meanwhile, I had wild pictures in my mind of a dog-eating electrophant, pictures based on a boyhood trip to Scarborough where, in Northstead Manor Gardens, they’d had a gaudily painted mechanical elephant with castors on its feet, which gave small children rides in its howdah.

There were indeed twenty concrete cells, or holding pens, for stray dogs. As we walked along the barred fronts, every one of the inmates came rushing up, tail wagging, wanting whatever it was we might have, hoping that we might represent something better than their clean, tidy, all-essentials-catered-for lives, which were, nevertheless, awful for a dog.

‘For every miserable, sinful bastard who abandons a dog, or mistreats a dog, there has to be a person of the opposite kind, who will take this dog in and give it love and care and respect,’ said our Jack.

I was right with it now. I was to be employed by the RSPCA to look after the kennels and the strays and keep all in as good a condition as possible, and the better I did my job, the more likely it would be that a citizen of Hull and environs would find one of my charges attractive enough to take home. I smiled. Goodbye, Labour Exchange. Hello, destiny.

*

A large part of the work was mucky and repetitive. I had to scrub out twice a day and all my guests had to be fed, watered and exercised. That much was set in stone but it didn’t take up all my hours. New dogs usually needed some extra attention, which was no problem, and in any time spare from my routines I was happy fooling around with all the dogs. Some of them clearly had never had even the most basic training. Some had never known the fun a dog can have, just by being a dog with a kind and caring human. Some distrusted humans entirely, and winning their trust was a kind of emotional torture because I knew the original distrust might eventually prove to be well placed, because here came the hard part.

The longer-term residents created special pressures. As the numbers mounted in the kennels – seventeen, eighteen, nineteen – it became more and more important to persuade the nice people who came looking for a rescue dog that the one nobody had wanted so far, the one in kennel nineteen, was the one they should have. If not, and of course this had to remain unsaid, the next dog in would put nineteen into twenty, and there was no twenty-one, only The End.

My powers of persuasion, I felt, were not as fully developed as they might have been. I read a book called How to Win Friends and Influence People. No use at all. I tried smooth-talking charm, but I never was cut out to be an estate agent. I tried little white lies, funny stories made up to make the less appealing hounds seem to be jolly characters, despite their shortage of good looks. I can’t say it worked very often. Something clicks between dog and potential owner, or it doesn’t. Even so, I could never give up, and I never could become immune to what our Jack had called ‘a personal failure’.

As kennel knave, I was mostly enjoying myself but it wasn’t what you might call a career position. I’d made my way into the RSPCA but at the very bottom, and I was looking for a step up. The most obvious, and the most exciting, had one big obstacle in the way.

A few of the staff were designated animal ambulance drivers. They had a duty rota, so many nights on call, so many not. If an animal was hurt in a road accident or needed care after any kind of incident, the RSPCA vehicle would attend. This was an idea I fancied, and one of the drivers had left. I’d still be kennel knave in the day but I’d be the RSPCA man at night, out there, in the world, driving to emergencies.

The obstacle was that I couldn’t drive. I had a brother-in-law who was sometimes persuaded by my big sister to take me out in his car but I needed practice, lots of it, and some proper lessons if only I had any money to pay for them.

At the age of seventeen, with nothing to declare but my ambition, I applied for the vacancy. When Jack raised the matter of my driving, I told him I’d booked some time off next week to take my test, and my only worry was the Highway Code questions. Jack told me to get swotting and not play with the dogs so much.

I couldn’t get my real test booked for another eight weeks so I did the obvious thing. I backed myself to pass first time, and told Jack that I had. He was so pleased that he never asked to see my licence, nor did the police, the fire brigade or anyone else who called me out over the next eight weeks, which gave me the driving practice I needed so that I won my bet with myself and passed the driving test.

Meanwhile, I met a drop-dead gorgeous blonde called Carol. I may have been a little naive but I actually thought that a penniless male kennel maid, whose idea of a good time was sitting up all night on the dockside waiting for a family of foxes to come out, stood a chance with a girl like that. Maybe it was the unpredictability that attracted her. She was expecting the cinema, chicken chow mein and a pound box of Black Magic chocolates. She got six penn’orth of chips and a ride in a small orange box of a van to rescue a cat.

The Hull RSPCA district was without an out-in-the-field inspector at this time, so a locum was brought in, and he would live in the flat above our office. He drove into the yard in his blue van and got out. Now, I had never seen an inspector before, and what I saw seemed like a vision. The uniform was like the police had, with smart tunic and cap, with RSPCA insignia and two silver pips on the shoulders, and I knew instantly that I’d seen my future.

The next weeks only made me more and more determined, as I got to know the man – only a few years older than me – and heard what he did and saw all the kit he had inside his van. He seemed like a free agent, responsible for solving every problem that came up, the dawn-to-dusk patrol, and that just had to be me.

My life now was entirely mapped out. My next job would be as an RSPCA uniformed inspector, and I wanted no more than that for ever and a day, and my companion along life’s rocky road would be Carol. There were several things wrong with this map. There could be no question of our getting hitched without the inspector’s job. Inspectors got a decent wage, a van to use whenever, and, above all, a house, but the minimum age for inspectors was twenty-two and I was only eighteen.

Time went by, then the good news. They lowered the age for inspectors to twenty. The bad news was that Jack retired, his place as manager was taken by Janet the assistant manager, and her place was taken by Herbert the senior supervisor, a man who hated all living creatures but especially cats, dogs and RSPCA ambulance drivers of whom he had previously been in charge.

Herbert and I did not get on. I could not understand what he was doing there and I must have made that apparent because he designated me as a special case. While maintaining his general dislike of anything that breathed, he never missed an opportunity to stick his knife into me, and a good one came up with his promotion.

‘Well, now, good morning young man,’ he said to me one day, his white-coated tongue slipping and sliding over his yellow, protruding teeth (he was an ugly sod as well as being so unpleasant). ‘I understand you’re applying to become an inspector.’

‘So I am,’ I said, smelling all sorts of large, long-tailed grey rodents.

‘I’m the assistant manager now,’ said Herbert, in such a way that suggested I should perhaps kneel and offer him an annual tribute of gold, silver and nubile maidens. As I failed to react correctly, he continued. ‘One of the assistant manager’s jobs, which is always done by the assistant manager, is to write the employment references. So when head office comes calling, asking for a reference for you, I shall have to write it. See?’

I certainly did see, and that future I had planned, with house, van, salary and Carol, vanished like my dad’s favourite proverbial substance, Scotch mist. I was devastated. Carol, bless her, did not come up with alternatives, such as my being apprenticed to a painter and decorator, or taking a position as an on-street sales executive with the Hull Daily Mail. Her view was that I would win through despite the best efforts of Hateful Herbert, but whether I would have done so without an exceptionally hairy dog, I don’t know.

This dog had been brought in to be put down straight away and, as ever, Herbert had volunteered to see to it. I saw him go into the little single-storey building set aside for the purpose, leading an animal I’d never seen the like of. It was massive and hairy beyond belief, like something out of a Hammer horror film. I supposed it was an Alsatian, perhaps crossed with something else such as a water buffalo, but it was one hell of a dog anyway.

Inside the building was the machine used in those days for putting animals down, the electrophanator. It sounds horrifying now but it was the technology of the time. It consisted of a box, an electrical transformer, and some crocodile clips on wires. You put the animal in the box, secured it with collar and leather thong, then attached the clips, one to each ear and one to a back leg.

There were two switches. The first delivered a shock through the animal’s brain, knocking it out cold. The second shock stopped the heart. If it sounds like execution by electric chair, it really wasn’t as bad as that. If it worked properly, it was as humane a method as we could have had then.

Things were not working properly for Herbert, though, with the hairy timber wolf. Shouts and curses were coming out of the killing shed, so I went in to see what was up. Really I had no business in there but it was on the way to the store cupboard where my stuff for cleaning out the kennels was. Herbert stopped cursing when I went in but I soon saw what was the matter. He’d got the dog in the box all right, and it was tied, although its head was out. As he approached with the crocodile clips the dog gave the most threatening and chilling growl. If Herbert put his hand anywhere near, he could expect to become eligible for disability benefit.

I had to smile at the thought as I headed for the store cupboard, but that little bit of amusement disappeared when I heard the dog cry out. I turned to look and there was Herbert with a length of four-by-two in his hands, about to whack the dog again. I ran over, shouting. If he did that once more, he would feel the four-by-two around his own earholes and might well experience new sensations in his private parts in connection with crocodile clips.

I was taller than him, younger and fitter, and so angry that Herbert could tell I was capable of doing what I said and more.

‘All right, then,’ he said. ‘If you’re so ****ing clever, ****head. You do it.’

This was against regulations. I wasn’t trained, I wasn’t qualified, and I’d never done it. Such thoughts could not enter my crowded brain, (a) because I wanted to spare the dog any more hurt, (b) because I was furious at Herbert, and (c) because I expected the dog to bite my hand off.

The animal seemed to trust me more than it had Herbert, and let me put the clips on its ears. Herbert meanwhile was making a big deal of attaching the last clip to the back leg. We stood back. Herbert threw the first switch.

We were expecting an alive dog to become unconscious, but quite the reverse happened. A quiet dog became mad, in all senses of the word. Screaming its wrath, it translated into a bucking bronco and began wrecking the electrophanator from the inside. The box, something about the size of a trap at a greyhound track, disintegrated before our eyes. The lid flew this way, the back door flew that way, and all the while the dog was howling, and it wasn’t the moon it was howling for.

Herbert ran from the room and banged the door shut behind him. I was rooted, unable to move as the hairy monster managed to hurl itself and the box onto the floor, where it burst open completely. The giant was free, and looking for revenge.

There was nothing in the room except another table like the one the electrophanator had been on. I jumped onto it and squatted on my haunches, watching wolfie padding around. He seemed even bigger somehow. Maybe he had a demonic spirit that fed on electricity.

Never in my life before had I been frightened of, or by, an animal. This was a new experience which, as the hound saw me and came my way, I felt would be a last as well as a first.

I didn’t know whether to try saying ‘Sit!’ in a commanding manner, or ‘Nice doggy, good boy’ in conciliation, but it didn’t matter because my mouth was so dry that I couldn’t say anything. All right, Carter, I thought, as the dog tensed, ready to pounce. I hope Carol will still like me with my throat torn out.

The dog reared up on its hind legs. I was motionless, still squatting, all sensations suspended other than fear. It put its enormous front paws on the table, one on either side of me, sniffed my face, and licked me.

Although it had been officially condemned, it had committed no greater crime than appearing to have no owner. It took me two days to find a family who would take it on and, while I was persuading Janet the manager to let me try to do that, I mentioned the matter of my reference and Horrible Herbert. That’s all right, she said. He’s new to that job. Never done one before. I’ll show him how.