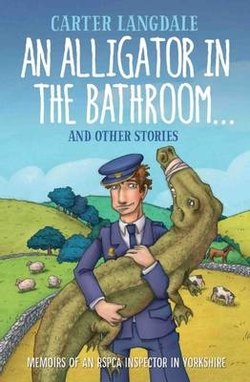

Читать книгу An Alligator in the Bathroom…And Other Stories - Carter Langdale - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

LORD OF THE FLEAS

ОглавлениеThe British police will cheerfully deal with a drugged up loony waving a samurai sword, or a gang of football hooligans fighting with knives and broken bottles. They’ll persuade a man to put the gun down and the Saturday-night drunks to go home, yet – in my time anyway – if they find a barking dog in front of them, they back away and call in the RSPCA to arrest it.

During my years of battling for animal welfare in Yorkshire, I had several encounters with pit bull terriers, one with a tosa inu (a huge red Japanese mastiff fighting dog) and others of breeds favoured by those persons in whom the police tend to have an interest. But that was always in town. Out in the countryside, I always thought I had a right to expect more animal sense from the local fuzz. Country boys, surely, sculpted from limestone and granite, men of the moors, hills and dales – they wouldn’t bother me over a dog.

I don’t know why I thought that, because my disillusionment came very early in my career, just qualified, new posting, keen as keen could be, a week into my dream job.

I was at home when the phone rang. In fact, I was in bed asleep. It was the desk sergeant at Scorswick police station, to say that several of his finest were being obstructed in the execution of their duties by a dog asserting its territorial rights. They’d been making a forced entry into a house and the animal didn’t like it.

The story was that a lady had rung in, saying she was concerned about the old chap who lived opposite, alone with the aforesaid dog. This man was something of a recluse so not much was seen of him anyway, but there’d been no signs of life from the house for a few days now. So, said the sergeant, as it was all happening in a village not far from my house, would I kindly pop round to this address pronto and deal with the canine in question, thus allowing the constabulary to resolve the matter?

Yes, all right, so I rolled out of bed, put on my RSPCA official-issue weatherproofs – it was mid-January as well as two in the morning – and found my hat and van keys. Setting off on a ten- or fifteen-minute drive, my consoling thought was that I’d soon be back in bed. Carol, as yet neither inured to, nor scarred by, long experience as an RSPCA inspector’s wife, was a quick learner and so hadn’t bothered to wake up when I went. On autosnooze, she wouldn’t even know I’d been out on a nocturnal call and so could continue to believe that our new life could only get better.

It’s a tiny village where I was headed. Not on the way to anywhere, it’s a no-through-road and, with nothing more than a church, a phone box and some houses lining an L-shaped street, plus a small manor to the side, it’s about as quiet as a community can be. It used to be a station on the old railway line but not even the ghost-trains stop there any more.

I arrived to find two policemen and a WPC by the front door of one of the standard council semi-detacheds. This must have been the greatest assembly of law enforcers witnessed in that village since the Norman Conquest. In some of the other houses’ bedrooms, the curtains were pulled aside for a better view of the unfolding Heartbeat-type drama.

‘Where’s Derek?’ said the senior cop, miserably. He was a gaunt, elongated type, a nightmare for police-uniform suppliers and off-the-peg tailors everywhere, who tend to expect men of six-foot-three to weigh more than eight stone.

‘He’s retired,’ said I brightly. ‘I’m the new boy. Inspector Langdale. Carter Langdale.’

‘Good man, Derek was,’ continued PC Grim. ‘No dog ever got the better of him. Mind you, he had the experience.’

‘We’re all fully trained,’ I said. ‘Six months’ hard labour.’ The grim one remained unimpressed. His nickname, I later learned, was Minnie, derived by evolution from Laugh a Minute.

The three coppers, repulsed by the proprietorial hound, had taken instead to looking through a small gap in the ancient army blankets which did for curtains in the sitting-room window of this fairly bedraggled-looking house. They had formed the suspicion that the old man, called Alf, was dead in his armchair. This meant they couldn’t enter the house after all. They would have to wait for whichever doctor was on the roster that night as police surgeon.

We stood around in the freezing cold, wondering where doctors could be at this hour if they weren’t in bed, waiting to be got up. The neighbour who had started the whole thing, a woman of considerable substance in a heavy overcoat, came out with cups of tea and told us that she did the old fellow’s shopping for him. He would put a list and some money in a milk bottle, and she’d leave the goodies on the step.

Although the list often specified Knight’s Castile soap and Omo detergent, it was believed that these items were for storage rather than use, saved against the Day of Judgement.

‘And he has fifteen cats,’ said the lady.

‘Fifteen?’ This was not a world record for a council house but it was still a fair number.

‘Fifteen. I don’t know why he stopped at fifteen but he did. Wouldn’t have no more. Maybe it’s the Jellymeat Whiskas,’ she said to me as the animal representative. I nodded, as if I knew what she was talking about. ‘And the Go-Cat,’ she added. ‘It all comes in a van once a month. Boxes and boxes. Must cost a fortune. What with them and that dog …’

She tailed off and looked at us all for confirmation that she was right in her opinion that there was no room in her village for such wild behaviour.

As the sun rose and the first daylight outlined the silhouette of the little range of hills to the north-east, we saw the lights of a car turning off from the main road. Those headlamps pointed our way. Hurray! At last. Our saviour was turning up and parking on the end of the row of vehicles – two panda cars, my van, a Ferguson tractor and a couple of Series 1 Land-Rovers which, in most other parts of the world, would have been at the back of the farmyard with chickens living in them.

The good doctor – young, blonde hair, anorak with fur-trimmed hood – had a Datsun Bluebird, a vehicle much favoured at the time by the medical profession for its reliability, though scorned by the fashionable for its anagram ‘durable dustbin’. Up the garden path she came, in a businesslike manner.

‘Morning, everyone. Right. Are we ready?’

I could see a war going on in Minnie’s mind. The policeman’s natural respect for the professions was battling with the evidence of his eyes and ears. Here was a girl who looked as though she should be working Saturday mornings in Boots the Chemist, who sounded like Angela Rippon, yet who claimed to be a doctor in the ancient Ridings of Yorkshire.

‘Er, we can’t go in yet, Miss, er, I mean Doctor,’ said Minnie. ‘There’s a dog.’

The doc looked baffled but took a pace or two back with the officers. It was time for Super Furry Animal Man to do his stuff. I leaned my patent grasper against the wall. This was a hollow pole with a braided wire running through double, making a noose at one end which I could pull tight at the other, very useful for keeping a dangerous beast away from one’s trouser turn-ups.

As soon as my hand touched the door, the dog started barking again. The police had broken the lock in their earlier assault so I just kept going, and when I saw my quarry I knew I’d have no trouble. No need for the grasper. This was a fat, short-haired, brown and white Jack Russell with bulging eyes, getting on in years, and it was absolutely terrified.

Barking its lungs out but wagging its tail furiously at the same time, the poor thing knew there was something dreadfully wrong. After days, I didn’t know how many, with its beloved Alf dead, no food, no water, it was utterly confused by life, me and the police. This anxious, troubled, tubby little animal wasn’t going to hurt anyone.

I shouted to the throng outside that I’d found the biggest and fiercest specimen of the Japanese Mouse Hound ever seen, and called to it in soothing and encouraging tones, feeling in my pocket for my dog lead. A police officer is never without handcuffs; an RSPCA inspector is never without a dog lead. At the sight of mine the terrier, perhaps of the view that leads implied long and strenuous walks over the hills and far away, turned and bolted into the sitting room, where it hid under the chair that Alf was seemingly asleep in. I’d never seen a dead person before. He looked rather grey but otherwise exactly like any bloke who’d had a few pints on a Sunday lunchtime and, after the roast beef and Yorkshire pud, was taking his customary afternoon nap in front of the fire.

I crawled on my knees towards the dog, held it by the collar and pulled it out from under with no resistance. As I stood, keeping the dog firmly in the crook of my arm and stroking it, I heard myself starting to explain to Alf what I was doing and why, and apologising for taking his dog away.

The name on the collar was Buster, and chubby little Buster was still quivering with fright but definitely getting calmer when I walked from the house. As ever, the constables expressed their admiration openly for someone who can deal with a barking dog. They parted before me like the waters of the Red Sea before Moses, or the waters of Whitby harbour before the good ship Lollipop. I nodded my acceptance of their esteem, all in a day’s work don’t you know, and said I’d be back later for the cats.

It was after nine by the time I got to the building designated as the RSPCA dog pound. This was an old lean-to greenhouse and potting shed where, in days gone by, municipal gardeners employed by Scorswick Urban District Council had pricked out their geraniums and transplanted their begonias for the floral clock at the entrance to the park. My inspector predecessor had picked up two mortuary slabs from somewhere, a mortuary I supposed, which he’d set up on sturdy plinths, for the purpose of examining animals and putting them down if he had to. We called it euthanising. The stuff we used, pentobarbitone sodium, trade name Euthatal, gave an animal a humane, painless and quick end but we were still killing it, and we didn’t do it without a very, very good reason. I had no expectations of that kind for Buster.

In my shed I only had accommodation for up to three dogs, plus cages and baskets for cats and birds. My dog pound was a staging post only. The Jack Russell and the cats would have to go to York, where we had substantial facilities and where we’d put the animals up for adoption. This would be difficult for Buster, I knew, because of his age, but we’d try our hardest. I went back to Alf’s for the cats.

Seeing the inside of the house in daylight was a bit of a shock. It was truly filthy. My shoes stuck to the carpet as I walked and made that squishy, suction noise. And the whole place stank to high heaven of cat pee. My, how it stank. How I’d missed the smell before, I don’t know. Must have been the excitement. Anyway, it was as near to overpowering as you could get without actually fainting to the floor. Never mind, I had to get on and find these cats.

I’d been told there were fifteen but I’d brought cat baskets for twenty. I would have to make sure there were no animals left behind and I knew that if there was the tiniest secret hidey-hole inaccessible to an RSPCA man, a cat would find it. In my time I have retrieved cats from up chimneys, under floorboards, behind the skirting, in the airing cupboard, under the kitchen sink. One of my colleagues once had to take the panelling off a bath to get a cat out, and there was absolutely no hint of how a cat could have wriggled in there. Here I was relatively lucky. On the tops of wardrobes and under beds was the extent of it and, after an hour and a half, I was sure I’d got them all, and fifteen it was.

Despite the wintry weather I was sweating buckets when I’d finished, so I threw my jacket and jumper in the back of the van with the last cat and set off for Scorswick in my short-sleeved shirt. I was debating whether to make the trip to York later today or tomorrow as I joined the dual carriageway into town. I flicked the indicator, turned the steering wheel and happened to catch sight of my arms.

You’ve seen those Tom and Jerry cartoons, where the cat puts his paw in the light socket and the shock makes him do a flying star jump with every hair standing on end, his tongue shooting out, his ears flashing on and off and his eyes whizzing around and around. That was me on the dual carriageway as I saw ten thousand fleas crawling about on my bare skin.

I must have been like a walking oasis when I went into Alf’s house, a mobile flea banquet for the starving, and there were so many I could hardly see a patch of myself. I did what I think most people would have done in such a circumstance. I panicked.

In trying to slap both my arms with both my hands at once, my attention strayed from the road. When it strayed back again I saw the rear window and boot of a gold Rolls-Royce about six feet away. I braked of course but it was no good. I clattered right into the back of him. I thought, ‘You must not release ten thousand fleas into the environment. Don’t get out.’ I also thought ‘Oh bugger,’ as I reversed ten yards and heard the sound of metal parting from metal.

The owner of the Roller got out all right, with some difficulty as he was the wrong shape for sharp movement. He cut more of a portly than a lithe and lissom figure, and very bristly he looked. I watched him stomp towards me and I could see he was no got-rich-quick barrow boy, flashing his wealth with a fancy motor. Rather, he was a retired major general, or a fourteenth earl, or Goldfinger. Those folk unfortunate enough to live in regions other than Yorkshire, and those who know it not, may believe that we’re all flat ’ats and whippets and frothy beer, but I can assure you that we do have gentry, and this was gentry all right.

His chestnut-brown Oxford brogues, polished to that deep lustre only possible with the finest hand-cured leathers, pure beeswax and a valet, thumped the tarmac with the sureness of a thousand years of superior breeding. His gingery Harris tweed suit with waistcoat, possibly a family heirloom but certainly built for posterity by the Indian and Colonial Outfitters, was amply cut, allowing for the largest lunches and the swiftest interchange of double-barrelled shotguns with his loaders.

As he stomped, he waved his arms about and tried to speak, his face suffused in a fairground kind of red, his purple nose pulsating, his moustache and equally hairy eyebrows twitching like three massive caterpillars in spasm. His spitting, frothing fury, and incomprehension of the inexplicable, could not have been greater had the barman at his club told him they were out of Angostura for the pink gin.

His car was, like its driver, a fine example of the species. It was a classic, the sort you could use as a tank if you fitted a cannon to it, with running boards and big headlights on the wings, and my Escort van was bound to have come off much the worse. So what was all the fuss about?

I thought I’d better get out after all. I said I was very sorry and, as he cursed me for a stupid oik of a peasant who should never have been granted access to the Queen’s highway but rather exposed on a hillside at birth, he saw me still slapping at my arms. He stopped dead. He peered. I jerked my thumb towards the van side behind me, where was written in large letters ‘RSPCA’.

‘I’ve just rescued fifteen cats,’ I started to say, ‘and the owner had been dead for days. Fleas were starving so they all …’ but my gentleman with the scratched Rolls-Royce was already backing off, his facial colours modifying to a certain extent, nearer to pastel shades with just a hint of white-not-quite.

His retaking of his driving seat was almost spring-lamb like, and his standing start with added blue smoke would have done credit to Stirling Moss. And I never heard another thing about it.

Rather than explain to my boss that I’d had a collision with a very heavy low-flying bumble bee, I thought I’d get the van fixed myself. I’d have to hope that the owner of the golden Roller wasn’t local, and definitely not someone who might one day call the RSPCA because his lady wife’s little dog was stuck down a badger sett. But that’s another story.

I drove as quickly as was reasonable to my cat and dog rescue centre, the old council potting shed, and installed the cat baskets. Not to worry, I told them. Only a temporary arrangement. I needed to get changed and have a bath. Before setting off home, I sprayed myself with a whole can of Nuvan Top, a highly effective flea killer now taken off the market because it was found to be carcinogenic. Nearly everything we used in those days has been taken off the market. It’s a wonder we’re still here.

Being bitten by fleas was an occupational hazard, which was why I hadn’t noticed much in the way of itching. The odd flea here and there, fair enough, part and parcel, but now I was standing in a crunchy heap of dead ones and I was quite sure they were no more than the advance party. The rest had yet to emerge from my nooks and crannies. I considered my next move. My wife Carol had to be told. There was no way around it. I stopped at the phone box and rang in.

You see, I said, I need a bath and a change of clothes because of this slight flea problem. No way, matey boy, was Carol’s response. I wasn’t going in the house covered in fleas. I wasn’t going in the house even with one flea that I knew about.

My pleas and entreaties, and appeals to the loving side of her nature, eventually produced a marginal softening in her attitude. A plan was agreed.

Her part of the plan was to run a bath and open the bathroom window (we lived in a bungalow). My part was to strip off on the back lawn in the perishing cold, stuff my socks, shirt and underclothes into an old feed sack ready for burning, leave my RSPCA gear spread out on the grass for dealing with later, and climb in through the bathroom window. I could see Carol looking out from the kitchen as I did all this, smiling, with a cup of tea in her hand and a piece of curd tart.

The bath was hot and foaming. Carol had dissolved half a bottle of car shampoo in it. I slid in and watched with some satisfaction as a layer of dead fleas formed in the suds. I pulled the plug, to get rid of this bath-load and start again with another, and the sheer volume of bodies clogged the plughole. I pushed them down with a nailbrush and, the bath clean, ran another tub of hot water.

There were hardly any fleas left now, no more than a hundred or so. I sank back and relaxed, and remembered an old story about how a fox is supposed to get rid of his fleas. He goes to a barbed wire fence, grabs a bunch of sheep’s wool in his mouth then jumps in the river. As he swims up and down, his fleas run along his nose to what they think will be a better berth on a sheep and, at the right moment, he says goodbye.

I too said goodbye as I pulled the plug and called to Carol that the delousing process was complete. While she’d watched me earlier through the kitchen window, she hadn’t only been enjoying my come-uppance from my beloved animals that always came first in our lives. She had also noticed that I had acquired approximately three million flea bites and that my body appeared to have been drained of blood.

She came into the bathroom spraying Nuvan Top before her and carrying a large bottle of calamine lotion, with which she began dabbing. Well, there wasn’t much of me left undabbed but what there was did credit to the cleansing powers of car shampoo. Even when I was mostly covered with fresh clothes and RSPCA uniform, my face and neck were still visible, skin of a deathly pallor liberally blotched with the crusty pinkish chalk of dried calamine.

Carol told me I should take the rest of the day off, having first burned my undergarments in the garden incinerator, sprayed my van and sprayed the uniform in the garden before hanging it on the line, there to stay through several nights of January frost until we could be sure all wildlife therein had been extinguished.

I did as I was told except for the day off bit. There were no SOS messages, for a change, so I was able to take the cats and Buster to York, where I was the source of much amusement and the inspiration for a series of imaginative and comical remarks which would run and run and never quite fade away. My fleas would be a feature of every Christmas do for years to come.

Shirley, the girl on the desk, reminded me of someone. Marianne Faithfull? Mary Hopkin? She sang a song especially for me, an old song by The Coasters called ‘Poison Ivy’.

‘It’s gonna take an ocean, dum-de-dum-de-dum, of calamine lotion. You’ll be scratchin’ like a hound, the minute she starts to mess around.’ Yes, yes, very funny.

I was fading as fast as the daylight as I drove home, feeling feverish, sweating but shivering with cold, and aching all over. I thought I must be coming down with flu but Carol had other ideas. She sent me to bed and called the doctor.

This doctor, quite unlike the breezy young woman earlier, was one of the old school, the sort who arrives in a dinner jacket if you call him out at night. He thought my story most entertaining and had no difficulty with his diagnosis: blood poisoning.

‘I have known very severe cases,’ he said, gravely, ‘where limbs have had to be amputated. In extremis, you understand. Another aspect of the presentation can be boils. Yes, you might come out in boils. If you do, I shall have to lance them, of course.’

Carol has always denied telling this doctor to wind me up but I don’t think she would have missed such a golden opportunity.

Despite having made his diagnosis, he went around the houses again with another examination. Pulse, stethoscope, torch thing for looking in your ears and eyes, thermometer.

‘Hm,’ he said. ‘Hm.’ He began to pack his bag.

‘Doctor?’ was all I could manage.

‘Ah, yes, Mr Langdale. Thing is, you see, I am not entirely convinced that your particular case would be best served by the modern treatment of antibiotics. I rather think the old traditional cure might be best. Yes. I think so. In your case.’

‘Traditional cure?’ I asked, thinking of leeches, or perhaps blood-letting.

‘Large doses of quinine and whisky. Half a bottle of whisky a day, for a week, should do the trick, plus quinine tablets dissolved in hot milk. I’ll instruct Mrs Langdale. Good evening to you.’

I had no strength to complain and sank into the pillows in despair. Amputations? Boils? A week? How could I take a week off? And what was Carol going to say about the cost of all that whisky? I didn’t suppose she could go to the off-licence with a doctor’s prescription and ask for a free half-dozen of VAT 69.

I heard the front door go and the sound of the kettle being put on. A few minutes later, Carol came in with some hot lemon and honey and two small white pills.

‘Marvellous,’ she said, keeping her face perfectly straight. ‘These modern antibiotics. So much power in a tiny tablet. Thank the Lord for medical science, that’s what I say. Two now, two every four hours thereafter.’ I swallowed the pills and washed them down with hot lemon. ‘You’ll be all right for work the day after tomorrow, and completely all right by the end of a week. Only thing with these pills is – no alcohol.’

The police, the police surgeon and the ambulance men who came to pick up Alf’s body, all complained about having a couple of flea bites but nobody thanked me for taking almost the entire swarm away with me. Social services had to fumigate the house twice before anyone would go in it again. York office found homes for all the cats and, after three months, an elderly couple who had lost their own dog offered to take Buster, so my first big job in my new world had had a happy ending, as I repeatedly told myself while hoping that none of my more athletic fleas had managed the leap from me to his lordship’s gingery Harris tweed suit.