Читать книгу When I Had a Little Sister: The Story of a Farming Family Who Never Spoke - Catherine Simpson, Catherine Simpson - Страница 11

Chapter Four

ОглавлениеEvery wall, every gateway and every tree on the lane leading to the farmhouse held a memory of Tricia. On my right was the wooden fence we leaned on to watch the mating ducks when she was five or six. ‘What they doing?’ she asked. ‘Makin’ friends,’ I said. On my left was the verge where our neighbour parked his flatbed truck – our stage for the plays I wrote, heavily influenced by Enid Blyton, in which I cast Tricia and Janet-from-next-door, mainly as dolls or fairies. (Play: A Lot of Rice for Tea; Characters: Rag Doll, Dancer Doll, Fairy Doll, Dolly Doll and six ‘Chinease’ Dolls.)

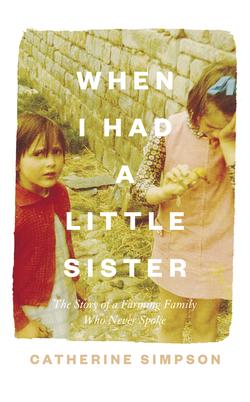

Me and Tricia in front of the wall we used as a stage and a catwalk

Past the verge was the head-high yard wall we balanced along for ‘playin’ bally’, never having had a ballet lesson. We took turns wearing a dog-eared 1950s evening dress donated to the dressing-up box by Great-Aunty Margaret and we ‘did twizzers’– arms outstretched and on tiptoes – until we legged ourselves up. At right angles was the stone garden wall we used as a stage to play ‘Miss World’, during which we draped ourselves in stuff from Mum’s ragbag. Elizabeth was compère and held a spoon or a drumstick for a microphone – ‘And in national dress, please welcome Miss Guam’ – as I set off down the wall wearing a 1940s tea-dress tied round with a tablecloth. ‘Next up, in her evening frock, it’s Miss Ceylon,’ and Tricia tottered down the wall wearing her vest, with a 1920s shawl around her waist and bits of broken chain-belt in her hair. On one occasion we used the wall as a catwalk for a fashion show with dresses we made from old cow-feed sacks, with holes cut for heads and arms and tied up with bale twine. The sacks made a ‘mini’ for Elizabeth, a ‘midi’ for me and a ‘maxi’ for Tricia, and left us covered in hundreds of tiny insect bites. We sampled the cow food-pellets – finding them salty and gloopy when chewed – but tried to forget about that fifteen years later when mad cow disease was all over the papers.

The day after Tricia died I was drawn back down the lane from Dad’s to the farmhouse, by a sense of disbelief, I think – a sense heightened by the many surrounding memories. The mortuary was closed for the weekend so I had not yet visited her body and I needed evidence it had happened; to see Tricia’s world without her in it, to check she was really gone.

Tricia beside the knicker bush, dressed as ‘Miss Ceylon’

Inside, the house smelled of stale tobacco – a smell that hit me then like a punch and still does. To me the smell of stale tobacco is the smell of anguish and hopelessness.

I stood at the door of the bathroom with its cold coffee and cigarettes on the wooden floor by the radiator. I moved about the house where I was born, a place that since yesterday had become the place Tricia had chosen to die.

In the living room I saw the lights were lit on the CD player. It was playing with the volume turned down – Tricia must have left it on a continuous loop. I squatted down to turn it up and the room filled with the pure, clear voice of Alison Krauss singing ‘When You Say Nothing At All’. The suddenness knocked me over and from a squatting position I plumped sideways onto the carpet.

In the kitchen I found the bin full of her long dark hair. I stared at it; so unexpected. She must have chopped it off last thing before she died because there was nothing thrown on top. Why had she cut her hair off? I did not reach into the bin and rescue a lock because the sight of her lovely hair there among the teabags and the soup tins reeked of despair and I couldn’t bear to touch it. Her long hair had been one of her trademarks ever since her early teens. There had been the occasional perm in the 1980s and it got shoved into a woolly hat when she was milking the cows or working with the horses, but it had never been anything other than long and dark and glossy, and now here it was tossed in the rubbish.

On the kitchen surfaces I found boxes and boxes of lotion for getting rid of hair lice. Tricia did not have hair lice; at that stage she didn’t have close enough contact with anyone to catch hair lice. I examined the boxes, baffled and heartbroken because these boxes reeked of despair too.

I learned later that a symptom of psychosis can be the sensation of a crawling on the skin that is impossible to alleviate. Memories of those boxes, and knowledge of the effort it must have taken Tricia to get out of the house and buy them for a problem she believed she had, swim into my mind often and have crystallized into the very image of loneliness.

I went into her bedroom but hated to look at her bed with the sheets and quilt in a tangled heap and some of the last items of clothing she had worn discarded on the floor. Signs of activity made her seem so close and underlined how recently she had been alive, how recently we should have been able to save her. The finality of death and the knowledge – although still not the belief – that she had gone shocked and re-shocked me over and over again every time my eyes alighted on some other personal item: her bedside glass of water, her toothbrush, her gum shield for stopping her grinding her teeth as she slept. The air was thick. It was as though the house itself was holding its breath.

I pushed open the door of my childhood bedroom – the familiar rattle of the latch, the whoosh of the door over the old shag-pile carpet – only to discover it had become a dressing room full of beautiful clothes. Tricia had been a farmer and a horsewoman; I remembered her in jeans and jumpers and grubby jackets with bits of straw clinging to them or maybe in a boiler suit, the top pulled down and tied round her waist as she wore a T-shirt in summer. This room used to contain two single beds and an ugly chest of drawers; now it appeared to contain a wardrobe and hanging rail stuffed with posh frocks. I found it hard to take in. I walked into the room and touched the hanging clothes. I could see a black satin halter-neck covered in red and yellow orchids and a black chiffon minidress with beaded cuffs, and alongside them were linen skirts, wool coats, silk blouses, fitted jackets, piles of scarves in every shade and texture, shelves of extraordinary shoes: gold sandals, red silk sandals, purple suede peep-toes, silver wedges and sparkly stilettos.

There were other items folded in big stiff carriers with the names of local boutiques on the side and with their labels still attached along with handwritten invoices for hundreds of pounds. So this was how Tricia had been spending her inheritance from Mum. There were clutch bags, large and small, in every colour. The wardrobe was full, as was the hanging rail which stood beside a full-length tilting mirror. It was a room devoted to glamour and beauty and femininity. I knew my sister was beautiful but I had not realized she possessed all these lovely things, or that she cared so much about her physical appearance.

Over the following months Elizabeth and I picked out pieces and took them home. Tricia was taller and more willowy than us, though, and one by one most of the outfits ended up at the charity shop.

My sister had shocked me by killing herself but maybe there were many things I didn’t know about her even though I had known her all her life, and almost all of mine. I had loved her. Things had been difficult as her mental health deteriorated, but I had always loved her.

All my life one gauge I used to decide if someone was acting unreasonably towards me was to ask myself: ‘Would I let them treat Tricia this way?’ I had always felt protective of her but in that I had clearly failed. I sat on the bed gazing in amazement at all these unfamiliar possessions – the possessions of a different woman altogether from the one I thought I knew – and I wondered: how well had I known her? How well can we ever know anyone?

As I sat in the farmhouse, dazed, the telephone engineer arrived to mend the phone. He thought the problem was a fault with an overhead wire, he said. He was standing at the back door and I told him what had happened the day before. His face became stricken and his eyes flickered over my shoulder as though drawn to witness the trauma. He picked up his enormous toolbag and headed into the garden to do the repair. An hour later he reappeared. It was all fixed, he said, but in future could we get Dad to build his enormous bonfires somewhere else. He gave me a meaningful look and cast a furtive glance towards the orchard, then mouthed the words ‘or they’ll charge him a fortune’, and with a tap on the side of his nose he was gone. An act of kindness from the telephone man seemed enormously significant. In those first raw days I latched onto all small acts of kindness and humanity.

We buried Tricia in her dressage gear – jodhpurs, fitted dark blue jacket, white shirt with a stock around the neck – and we put her riding crop in her hand. I never saw Tricia practising dressage, even though she had been doing it for some years, because she was shy about being watched. But I knew how much pride she took in it. I knew, on a good day, how enthusiastically she’d tell you about her ‘perfect trot–canters’ and her ‘flying changes’. My memories of Tricia riding were of the less-controlled variety. For instance, the first time she was put on the back of a friend’s horse, aged six or seven, and the horse bolted down the lane. I remember the screams of the friend’s mother and the panic followed by the relief when the horse was captured and led back – with Tricia still in the saddle, an enormous grin on her face.

As we prepared Tricia’s outfit, Alice, a lady from the village, showed me how to tie the stock so I could explain it to the undertaker. We couldn’t find Tricia’s stock pin so Alice went home and brought back a gold stock pin with a little horseshoe on it which strangely looked like a symbol of good luck. Elizabeth spent hours polishing Tricia’s riding boots to a glassy sheen, all the time aware that the undertaker might have to slice right up the back to get them on.

There was a line of framed photographs along Tricia’s mantelpiece in the farmhouse kitchen showing her Labrador, Ted, and her old collie, Roy, alongside pictures of her long-gone mare Hattie shoving her head over the denim-blue stable door. We took these photographs, and one of Dad sitting on the old water trough with Roy smiling at his feet, and placed them around her in the coffin.

It was months before I realized that the only photograph we left behind on the mantelpiece was one of the whole family together: my mum (Margaret), dad (Stuart), Elizabeth, Tricia and me, at a family wedding smiling in our Sunday best.

Dad, Mum, Me, Tricia and Elizabeth at Cousin Mary’s wedding

Maybe in choosing the photographs of her animals to go in her coffin – as her ‘grave goods’ – we had unconsciously acknowledged that animals were a constant source of comfort to her and had never let her down whereas we, her family, had.

The eventual emptying of the farmhouse after Tricia died, a job we put off again and again for months, was a huge task because my grandparents, David and Marjorie, had moved into the farm in 1925 and it seemed little had been cleared out since; consequently generations of belongings had composted over the years and it felt as though we were unearthing an architectural dig. The process of untangling our past called for decision after decision which seemed to accumulate in weight as we progressed.

In fact some of the clearing had been done, in 2005, eight years before Tricia died, when we sold the old barns for development. At that time the great hay barn, the cowsheds, the old stables and pig pens had to be emptied of what amounted to my mother’s ‘overspill’. My mother was a shopper. In particular she was a shopper of wool and cloth, sewing paraphernalia and gadgets. She loved gadgets for cleaning, gadgets for cooking, gadgets for sewing and knitting. My mother had an eagle eye for advertisements featuring anything newfangled that came with an instruction book – things that made big promises about saving time and labour – and she would seek out these expensive gadgets and buy them. Her idea of a birthday outing was a drive to Lakeland Plastics in its original Lakeland home to buy more gadgets.

When it came to the clearing of the barns in 2005 we were faced with chest freezers and suitcases and cardboard boxes full of mouldy wool and bolts of cloth still with their labels attached showing the size and price – which was always startlingly high – plus baffling gadgets that had never been assembled: gadgets for cleaning windows, steaming carpets, cutting out dress patterns, assembling quilts and knitting complex designs.

Anyone would think my mother enjoyed cleaning and housework, but this was not true; in fact she despised the excessively house-proud. She liked to declare that only boring women had tidy houses. I suppose her constant purchase of gadgets for cleaning was a way to make housework more interesting, or at least put it off for a while in favour of another shopping trip. But she adored handicrafts and, after packing the farmhouse to the gunwales with cotton bobbins, buttons on cards, zips in every colour and endless dressmaking patterns, as well as the wool and cloth, she set to filling the barns and outhouses with her haberdashery as well.

In the year 2000 Mum and Dad moved out of New House Farm to a newly built dormer bungalow up the lane. Tricia was left to live alone in the farmhouse, much to her satisfaction, although she was less thrilled when she realized the house was to be left still packed with stuff because, as it turned out, although my mother had moved she still reigned supreme – now over two houses – and her possessions left behind in the farmhouse and barns (until the barns were sold) must not be touched. Meanwhile Mum set about filling her new house with stuff too.

My mother’s mood – often low and downbeat – could be transformed by ‘newness’. She was excited by technology and innovation. She bought shares in the Channel Tunnel as soon as it was possible, went to ‘computer classes’ before I ever did, and invested in bio-tech companies, enthusiastically telling you which diseases her investments were about to cure. She was dismissive of self-appointed gurus who advised you on how to live your life (‘Huh! Who says? Experts!’) but admired inventors and scientists.

She didn’t like to see me hand-sewing even though I found it satisfying. When I was twelve years old I stitched a patchwork quilt and she would watch me, her hands twitching, frustrated. ‘You’d do it much quicker on a machine,’ she kept saying. My needle and thread flew over the quilt in a ham-fisted front to back motion, producing stitches so neat and tiny they were barely visible. ‘Leave her,’ said Dad. ‘Let her do it if she likes it.’

When we sold the barns in 2005 we also sold the outhouse that had been used by my Grandad David – Dad’s father – who we always called ‘Gran’. This outhouse, known as ‘Gran’s Dairy’, was Edwardian red-brick and had been used by Gran’s wife, Marjorie, to make cheese in the 1920s and 30s. Inside it was floor to ceiling white tile with a monumental cheese press. When I was growing up in the 1970s the back room of the dairy was Gran’s den and he spent every evening in there sitting in his old armchair, with his fuzzy black and white television, his wireless set, his crate of brown ale and his stack of Westerns from the mobile library.

David (‘Gran’) and Grandma Marjorie married and moved to New House in 1925

The farm collie and next door’s terrier and our half-feral cats joined him in front of his two-bar electric fire and under the halogen pig lamp that shone orange on his white hair to keep him warm. Cats draped themselves about his shoulders and perched on his head to share the warmth and he didn’t mind a bit. He would chew lumps of bacca he had cut off rope-like tobacco he called ‘twist’ with his penknife, eventually spitting the stuff out on the stone floor, like some character from the Wild West, where the dog would eat it.

Gran had retreated to his den when my mother and father married in the late 1950s. By then he had been widowed many years following Grandma Marjorie’s death in childbirth. Gran lived with us almost until his death, outliving Marjorie by fifty years.

He was known to almost everyone as Gran, possibly because Elizabeth couldn’t say Grandad as a toddler, although in fact no one really knew, and we didn’t bat an eyelid to hear ‘Gran’s having a shave’ or ‘Gran needs more bacca’ or ‘Gran’s checking his mowdy traps’. One of Gran’s hobbies was catching moles (‘mowdies’). He set vicious claws into the ground to crush the creatures as they burrowed between molehills which ruined the grass. I once discovered a mole rooting up the seedlings in a tray of baby lettuce on the back yard. My schoolfriend and I raced to save it as Gran hovered nearby shouting ‘Kill it! Kill it!’

He used the same penknife for cutting bacca, paring his nails, peeling apples and setting his mowdie traps. The penknife lived in the pocket of the old coat he always wore over his ancient trousers and jacket, and which was wrapped round at the waist with a length of baling twine.

By the 1970s Gran’s Dairy was lined with Marjorie’s old cheese shelves which were packed with the flotsam and jetsam of his farming life: decoy ducks, empty milk bottles and rolls of wire, all coated in a thick layer of aged dust. Pushed up against them was his armchair, ingrained with grime and packed with newspapers where the springs used to be.

Bit by bit Gran’s Dairy filled up with broken furniture that Mum wouldn’t have in the house: legless chairs, chairless dining tables, overwound clocks and a wooden fire surround, all dating from Marjorie’s day and too precious to Gran to throw away. The only things my mother seemed to want to get rid of were things that were precious to other people.

When one of the cats died on a sofa in there, another cat flattened the body and turned it into a bed before anybody noticed.

One day a barometer slid from the wall and smashed. Mercury rolled around the stone floor and we stamped on it watching it shatter and gather itself like the quicksilver it was until it finally splintered and was lost down the joins and the cracks.

Gran came into the farmhouse to sleep and to eat his meals. He would peer through the kitchen door to see what was on the table and if it had a crust or a hard skin he’d go back for his teeth. He ate everything; fat, gristle, the lot, both courses from the same plate, wiping it clean in between with a slice of bread. ‘You don’t know you’re born,’ he’d say if he caught me wrinkling my nose at the sight of custard covering traces of gravy.

Visiting children found Gran intimidating but he had a sense of humour – as dry as dust and well hidden. One time I remember hearing his rumbling chortle was when a caterpillar, boiled in its entirety, rolled out of a cauliflower floret I’d just chased round my dinner plate.

On our birthdays he gave us fifty pence. He’d root through his pockets, sorting handfuls of washers and bits of straw, until he found a silver coin which he’d look closely at then hand over with a faint chuckle. Life was tough and we’d better get used to it.

He was a veteran of the trenches at Ypres where he was shot through the shoulder. In hospital in Boulogne he learned to thank the nurses – mercy boo coo.

When he was an old man he said little. Aged twelve I went out to his dairy with my notebook and pencil to ask him questions for a school project about ‘The Olden Days’.

‘Gran, when you were little what did you do on a Sunday?’

He tamped his pipe and puffed a bit to get it going.

‘Put on me fustian breeches and watched tide, ’appen.’

I wrote: ‘watched tide’.

‘What did you do during the war?’

He did a silent kind of a snort, thought about it a minute then put his head back.

‘War … huh.’

As an adult when I reminisced about Gran spending time in his dairy, my dad’s sister, Aunty Margaret (another one), was upset that he should be remembered thus. She recalled him during her childhood as ‘a smart man’ whose successful efforts to keep his family together, despite the death of his wife, were nothing short of heroic.

Gran fought in the trenches at Ypres in the First World War

Not all the furniture from Marjorie’s day ended up in Gran’s Dairy. A mahogany glass-fronted cabinet stacked with silver tea services, dating from David and Marjorie’s wedding, and with drawers full of sepia photographs, remained in the farmhouse sitting room. If we opened the drawers and asked about the people in the photographs, Mum told us: ‘Shut that drawer and stop rooting.’

Years later, when we took the photographs from the drawer and tried to work out who they were, there was nobody left to ask and all we had was a sea of sepia strangers whose lives and stories were lost to the past.

Gran kept leather-bound farm diaries detailing animals that went to market, crops planted and cheese produced. On 15th May 1938, the day his wife died in childbirth, it says only ‘M died’ and after that there are no more entries. He found my dad who was milking the cows that day and, shaking his head, said, ‘Never mind,’ then with another four children to think about, including a newborn baby, he left my dad to finish the milking.

My twelve-year-old dad never went to school again. The truant officer poked his head into the barn every so often as my dad forked hay or fed the calves. ‘Try to get to school today, eh?’

Eighty years later my dad keeps a postcard in his desk, addressed to ‘Master Stuart Simpson’, sent by his mother from hospital in Preston as she waited to give birth. The card shows a painting of a spaniel. ‘Wasn’t Preston lucky on Saturday. I heard it on the wireless. Hope you are doing your best for Daddy.’

He still cries when he sees it.

Also in his desk is the bill from the hospital for the maternity services his mother received. A bill issued to her husband after her death.

Grandma Marjorie was survived by her baby girl, who was also named Marjorie. As a girl, Young Marjorie was red-haired and sparky. She worked on the farm, throwing herself into everything – baking with gusto and covering herself and the kitchen with flour, chopping logs and accidentally hacking her finger-end off with the axe. She got engaged to a local undertaker called John but Young Marjorie had a digestive disorder and no one realized how serious it was until she collapsed and died. Instead of being married in 1959 she was buried. This was four years before I was born. She was twenty-one.

Young Marjorie, aged 21, the year she died

I think it was in 2005 that the Kilner jars of damsons, picked from the orchard and bottled by Young Marjorie, and that had been lining the far-pantry shelves my entire life, were finally thrown out.

It took me a long time to realize that Grandma Marjorie was so scarcely mentioned I didn’t have a proper name for her and had settled on ‘Dad’s Mum’. Stories about her were rare not because nobody cared but because Dad and Gran cared so much. On this subject, as on so many others, we were dumbstruck.

In my lifetime the cupboard halfway up the farmhouse stairs had been painted shut with layer upon layer of thick gloss paint. As a child I pressed my eye to the keyhole, shone in a torch and saw book spines untouched for more than twenty years.

Books were my escape from a world with the wrong kind of drama in it. I hungered for stories and books to make reality fall away.

I read to find circuses, wild animals, long dresses, castles, enchanted forests and magic faraway trees. Re-entering real life after being lost in a book was painful and disorientating.

At the table I read the back of the cereal packet. I read the primary-school library over and over again. I read the set texts Elizabeth brought home from secondary school: Animal Farm, White Fang, The Otterbury Incident. I read the Daily Express. I read the Radio Times. When I ran out of stories I read the dictionary. I compiled my own dictionary of words I didn’t understand. ‘Tippet: a woman’s shawl; Brougham: a horse-drawn carriage; Stucco: plaster used for decorative mouldings’ reads the list, in what must have been a Georgette Heyer phase.

Until sixth-form college my reading was unguided so I read Tender is the Night but not The Great Gatsby, Anna Karenina but not War and Peace, Lady Chatterley’s Lover but not Women in Love. I chose books from Garstang Library purely on covers and titles. I read the entire works of P. G. Wodehouse and Agatha Christie, fascinated by their versions of English country houses. I read everything Catherine Cookson wrote and pronounced ‘whore’ with a ‘w’.

My mother brought back library books in the Ulverscroft Large Print series for me, knowing I wore glasses without understanding they were for distance not for reading. Producing a child who needed glasses was perturbing for my mother: ‘I fell down stairs when I was expecting. I didn’t make such a good job of you.’ I never told her I could read small print perfectly well, because I liked getting lost in the great big words.

But my mother did give me occasional random compliments. ‘Your ears lie good and flat. The back of your head is well shaped. Your eyebrows suit your face.’

I was short of books and often panicked about it, so one day I prised open the cupboard door on the stairs as the hinges made sharp cracking sounds and splinters of paint flaked off. Inside were dusty and faded hard-backed books. I inched one out and shut the door, pressing the cracked paint on the hinges back into place. The book was Sue Barton, Senior Nurse and was signed on the flyleaf ‘Marjorie Simpson, 1956’.

I took it downstairs and sat on the hearthrug in front of the open fire. My mother said: ‘What’s that? It looks like rubbish.’ I struggled through a few pages but there was no adventure here; it seemed to be about nothing but a nurse in trouble with ‘Sister’ for being on the ward with her ‘slip’ showing. My mother was right, it was rubbish. I squeezed my hand again between the painted-up doors, scraping my knuckles as I put Aunty Marjorie’s book back in the past.

I have wanted to be a writer for as long as I’ve been able to read. I wrote my first book aged nine in a hard-backed Silvine notebook with marbled endpapers. It chronicled the adventures of ‘Sandra’ and ‘Barbara’ – two girls who apparently went everywhere (mainly to dancing lessons) on horseback and had a sworn enemy called Mr White. My best friend, Alex, and I acted out the adventures of Sandra and Barbara every day in the school playground.

My writing ambitions faltered after that because writing became embarrassing; self-indulgent and pointless, particularly after a boyfriend found something I’d written when I was a teenager and flicked through with a sneer on his face. ‘What is this? What do you think you are – a writer?’ Later I discovered he had scrawled in the margin ‘This is stupid’, in case I hadn’t got the message.

My mother read gardening books, dressmaking books, yoga books and recipe books, but no fiction. She referred to fiction as ‘made-up stuff’, and asked ‘why do you read that?’

I left school at eighteen with dismal A-level results and became a bank clerk then a civil servant, jobs taken for the sake of taking a job – because that’s what you did. I also had to pay the mortgage I’d saddled myself with aged nineteen – because buying a house was something else that you did. In my mid-twenties I retrained as a journalist because that seemed an acceptable way to earn a living with words. My mother died when I was forty-two and shortly after that I began to write pieces of fiction and memoir. It took me until my first novel was published, when I was fifty-one, to realize the death of my mother and the birth of my writing were linked – that in losing my mother I had acquired the right to write my own life.