Читать книгу When I Had a Little Sister: The Story of a Farming Family Who Never Spoke - Catherine Simpson, Catherine Simpson - Страница 13

Chapter Six

ОглавлениеMy sisters and I were born at New House Farm in the sitting room; the same room in which my dad was born thirty-eight years before me; a room otherwise only used on Christmas Day to watch films and eat Quality Street; a room that would one day have Pete and Trev strolling round it talking about pianos and cranes and brown furniture as they weighed up brass pots and pieces of china and searched for marks on the silver.

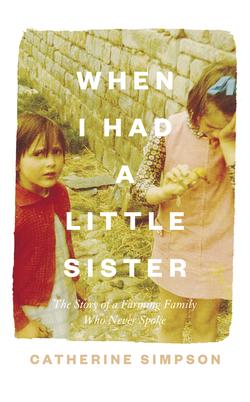

Me and Elizabeth ‘helping’ Dad mend a puncture around 1966

On the day I was born, Nurse Steele came with her canister of gas and air to deliver me, as she had done three years earlier when Elizabeth arrived and as she would do three years later for the birth of Tricia.

On that occasion Elizabeth and I were not told what was happening in the sitting room directly below our bedroom. We woke one morning to discover our bedroom door so firmly shut it was impossible to open. Was it locked? Were we trapped? We hammered and screamed ‘Help! Help! Mummy! Mummy!’ until Dad wrenched the door open. ‘Sssh!’ An aunt took us downstairs and gave us Chocolate Fingers and milky coffee in front of the kitchen fire to keep us quiet until we were eventually taken into the sitting room for the first sight of our new sister.

We were led through the lobby and the sitting-room door, past the grand piano, until I was on eye level with the bed that my father had brought downstairs the week before for the arrival of this baby. Mum was propped up against the pillows, smiling a little, wearing a crocheted bed jacket with satin ties. Tricia was lying on the counterpane wrapped in a white blanket. I think Mum probably decided not to be cuddling Tricia as we came in for our first look so we wouldn’t be jealous.

Nurse Steele said, ‘Isn’t she lovely?’ and I stared at this red-raw mewling thing moving in slow motion. I looked sidelong at the smiling nurse – was she laughing at me? Why was she saying it was lovely? I felt betrayed. This was not the playful, chubby-cheeked baby I had been promised – the one I could be ‘good’ with and share my toys with; I was doubtful it was even a baby at all. It reminded me of new kittens when you first found them in the barn in the nest; eyes shut and rooting for milk. Nurse Steele gave a tinkling laugh and I looked at the carpet.

Someone had played a dirty trick on me.

Years later Tricia claimed she could remember being born – the violence of it, the darkness, the eventual light. When I told Mum she snorted and rolled her eyes. As if!

She banged her Daily Express, with an expression like Whistler’s mother, and that was the end of it. Perhaps the act of childbirth was below my mother’s dignity and she didn’t want anyone remembering that.

In our family, it seemed sitting rooms were for Christmas, for being born or for dying. This was the first room you saw, and the last.

The first dead person I saw was in 1973 when I was nine years old and I was taken to see my maternal grandad lying in an open coffin in the best sitting room of my grandparents’ farmhouse. We rarely got to see the inside of this room but there was no time today to examine the upright piano or the cabinet of china ornaments – including a china cat about to kill a cowering china mouse – or the eight black and white wedding photographs of my mother and her seven siblings framed and hanging on the wall like a catalogue of wedding styles through the 1950s and 60s.

No, today the settee had been pushed back against the piano to make room for the coffin, which was shiny oak, top of the range, and resting on some kind of stand. Grandad Ben was wearing a white satin shroud and was surrounded by white satin padding. He had died of lung cancer after being ill for only two months. He had rapidly grown thinner and weaker and his cheeks had sunk but nobody had told me he was dying.

His bed had appeared unannounced and unexplained in the living room of my grandparents’ farmhouse where the old sofa used to be – the one we sat on to watch The Golden Shot and Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased) on a Sunday afternoon while we ate finger rolls with mashed egg and salad cream followed by Great-Aunty Margaret’s jam slice – and he had gathered ever-more bowls and containers around him to cough and spit into; but still nobody told me he was dying.

Illness was frightening; adults whispering and shaking their heads was frightening. Frustrated that he looked worse every week and puzzled when Grandma smiled a little too brightly and said, ‘He did so well!’ when all Grandad had done was walk to the bottom of the yard and back, I asked my mother: ‘When’s Grandad going to get better?’ She was stirring a pan of gravy with a wooden spoon and kept her eyes on it and said, ‘Maybe he won’t.’

Shock trickled from the top of my head to the tips of my toes like a bucket of iced water. I had never considered there were important things grown-ups could not fix.

I wondered if my mother would ever have told me if I hadn’t asked.

When he died my mother asked me and my sisters if we wanted to go and see him. Grandad was six feet tall, a strong farmer with a forceful personality, and now here he was in his coffin looking like a waxwork. We were told his body had been embalmed so he would never change. This, I understood, was because Grandad was a Very Important Person; someone his family looked up to and respected without question. Grandad was a Worshipful Master in the local lodge of the Freemasons; Grandad was a Duchy of Lancaster tenant and had been invited to meet the Queen at St James’s Palace more than once; Grandad had played rugby for the Rochdale Hornets and as a young man had been sparring partner for professional boxer Jock McAvoy, known as the Rochdale Thunderbolt; Grandad was a personal friend of Gracie Fields and on the marble mantelpiece by the television was a postcard from the island of Capri to prove it, curling at the edges and a little singed from when it had drifted into the open fire, but still legibly signed ‘best wishes, Gracie’. Grandad was all-knowing, all-powerful and immortal.

We edged towards the coffin. I could see Grandad’s profile; it was him and yet not him. I wasn’t sure that embalming was such a good idea if it meant he would look like this for ever. His hands lay white and frozen on the shiny satin shroud. They looked different; they looked very clean. A farmer’s hands never look very clean, no matter how much they scrub them with globs of Swarfega. I learned years later when my own father was ill in hospital with the first of his bouts of cancer that if a farmer’s hands are not ingrained with soil he is either dangerously ill or he is already dead.

My mother leaned over the coffin and kissed Grandad’s cheek and I watched, horrified. I’d never seen my mother kiss anyone before, let alone a dead person.

I’d been reluctant to kiss Grandad when he was alive because he and my uncles had a habit of grabbing your face and rubbing their stubbly chins on you. This painful experience was known as a ‘chin pie’ and was supposed to be funny. It certainly made my uncles roar with laughter but it had made me wary. I knew on this occasion Grandad was not going to give me a chin pie but I still didn’t want to kiss him.

Elizabeth, Tricia and I inched nearer the coffin, side by side, halting at a safe distance. Grandad had been a generous man who regularly went to the cash-and-carry to buy sweets in wholesale quantities for his grandchildren and handed them out like Father Christmas every Sunday, yet bellowed at me for switching on the stair light in the farmhouse to find my way to the loo because I thought the turn in the creaking stairs was haunted. Grandad was a man who read Titbits yet disapproved of many things including a child using the word ‘pregnant’ (‘don’t let your grandad hear you saying that word’). Grandad travelled the world with Grandma Mary, including cruising to South Africa, yet I once saw him pluck a partially sucked sweet off my cousin’s jumper, say ‘waste not, want not’, and eat it. I had joined in games where he sat beside a doorway and tried to whack you with a rolled-up newspaper as you ran past, partly excited but mainly terrified.

‘Say goodbye to your grandad,’ my mother said. She started to cry. I watched, frozen.

I’d never seen my mother cry before either.

I learned when Grandad died that certain rituals follow a death; relatives gather together and speak in undertones and drink tea, but as kids my twenty-odd cousins and I had not yet learned to respect these rituals. On the Sunday after Grandad’s death, but before his funeral, we played Blind Man’s Buff along the farmhouse corridor like on any ordinary Sunday; except this time not only were we trying to evade the blindfolded ‘blind man’, we were trying not to touch the sitting-room door because it had dead-Grandad behind it. If one of the younger cousins stumbled against the door an older cousin would chant, ‘You’re haunted! You’re haunted!’ and the younger cousin would start blubbering, whereupon an aunt would poke her head out of the kitchen and hiss, ‘Ssssh! Don’t you know your grandad’s dead?’ as though there was a danger our racket would wake him up.

I wanted to go to Grandad’s funeral but was told, ‘No, and don’t ask again.’ Neither Elizabeth nor Tricia expressed any interest in going. My mother was knocked sideways by the death of her father and she probably thought she had enough on her plate without taking me. I considered this unfair – especially as this was not the first funeral I had been banned from attending.

Five years earlier, when I was four, I’d asked to go to my first funeral when Old Jack died.

Old Jack was our neighbour and looked like a manifestation of God himself – if God ever wore fustian breeches and lived in a red-brick cottage in the middle of Lancashire. He had white hair, a white moustache and a mahogany desk full of chocolate.

We took up his dinner (his midday meal) every day on the tractor the quarter of a mile from our farm. My dad drove and Elizabeth and I bounced along clinging to the tractor cab, struggling to keep the plate straight to stop the gravy and the peas from dribbling into our wellies.

We’d find him sunk in his armchair by the open fire. He wore a jacket and weskit and trousers shiny with age and of an indeterminate colour best described as ‘old’. He had pockets of mint imperials and barley sugars.

He was glad to see us and would greet us with a ‘How do’ and creak out of his chair and root around in his antique desk to find each of us an Aero bar. The desk had shiny black knobs down each side and soft fraying leather on top and a secret drawer. Old Jack showed us how to slide out one of the knobs to open the secret drawer.

Old Jack’s cottage had no running water, no electricity and no gas. It was 1968, and by then his wife had been dead more than thirty years. Old Jack had lived there on his own since his brother Old Jem died of lung cancer in 1962. Old Jem had never smoked but had spent every night huddled over the coal fire in the cottage to keep himself warm. Old Jack had had two brothers and a sister, all unmarried, who had lived with him after his wife died and who themselves then died at seven-year intervals – Agnes was the first to go in 1948. She was a woman with an ‘erratic mind’ who ‘fizzled out somehow or other’, as my father remembers it. Seven years later Bob shot himself with a 12-bore shotgun on the back cobbles of the cottage. Bob was seventy years old, newly retired and unable to face life without his job on the dykes.

My dad had been visiting Old Jack every Sunday evening since the 1940s and for years there had been games of Nap and Pontoon, with Agnes, Bob and Old Jem, playing for pennies; the oil lamp rocking on the table as they excitedly slapped down the cards.

By the time Old Jack died in 1968 we’d been delivering his meals by tractor every day for ten years and we were the closest thing he had to family.

A year or two earlier when Old Jack was well into his eighties, he’d turned up at our farm on his bike with his Last Will and Testament shoved in his weskit pocket. He was leaving the lot to my dad and another neighbour, he said; his tiny cottage, its contents and his ten-acre meadow with his cow in it. To Elizabeth he was leaving his ebony and gold antique chiming clock, to my baby sister Tricia he was leaving his Edwardian sofa, and to me he was leaving the loveliest thing I have ever been given – the beautiful antique writing desk with the shiny black knobs and the secret drawer full of chocolate.

Old Jack died ‘of old age’ in his sleep when he was eighty-six and he was laid out in an open coffin in the cottage’s tiny sitting room. I was four years old and wanted to go and see him.

‘I want to see Old Jack.’

‘No.’

‘I want to see him.’

‘Stop mithering.’

‘What does he look like?’

‘Like he’s asleep. Now stop mithering.’

‘Is he in bed?’

‘No, he’s in a coffin.’

‘What’s a coffin?’

(Sigh.) ‘It’s a box you get buried in. Now that’s enough.’

‘What kind of a box?’

‘Oak with brass handles. It’s a box that’s oak with brass handles.’

I thought about this. A few years later I would learn about oak boxes with brass handles; I would see them on The Dave Allen Show where they were usually balanced on the crossbars of bikes or slithering out of vans and sliding down hills chased by the vicar. But at the age of four I had never seen one and they intrigued me.

‘Can I go to the funeral?’

‘No.’

‘Why not?’

‘You’re too young.’

‘Why?’

‘Children don’t go to funerals. Don’t ask again.’

‘Why?’

‘Ask again and you’ll go to bed.’

Dad brought the antique desk from Old Jack’s with the tractor and trailer. He wrapped his long arms round it and staggered into the house with his knees bent. Unlike with Great-Great-Aunt Alice’s bracelet and evening bag, my mother did not consider the desk rubbish. She said, ‘That desk’s mahogany, it’s a Davenport – put it straight in the sitting room.’ That meant I’d only see it on Christmas Day or if somebody was born or if somebody died.

It was not going in my bedroom because it would get ruined. It was too good, my mother said. It was too good to get scribble gouges and felt-pen marks and cup rings on it. The mahogany desk was going in the sitting room and that was that.

Occasionally over the years I would turn the brass knob on the sitting-room door and push the door over the thick carpet and stare at the mahogany desk wedged between the grand piano and Tricia’s Edwardian sofa. It was a long way away; acres away over the swirling turquoise and gold carpet and flanked by tarnished photograph frames and piles of sheet music and china vases that I wasn’t allowed to touch either. It was far, far away – much farther away than it had been in Old Jack’s living room. It was not covered in scribble gouges or felt-pen marks or cup rings. It was not ruined, but its secret drawer was never opened and no one ever stroked its frayed leather top. No, the mahogany desk may not have been ruined but it was dusty and fading and empty of chocolate and so far away it was lost to me.

One way or another there seemed to be a lot of death about as we grew up – Old Jack, Great-Great-Aunt Alice, Grandad, endless farm cats, sickly piglets and occasional calves born dead, which is possibly why I was obsessed with ghost stories – tales of people coming back, people who were dead but not truly gone. I read and reread Aidan Chambers’s Ghost Stories and More Ghost Stories and, when all else failed, my Sunday-school prize, Saints by Request.

One afternoon Wuthering Heights came on the television. Mum said, ‘You might like this, it’s a ghost story.’ I watched, enraptured by Merle Oberon and Laurence Olivier. The following day Mum went specially to John Menzies in Preston and bought me the book. I was ten years old and sat on the hearthrug doggedly reading it although I did not understand many words and had to skip Joseph and his broad Yorkshire dialect altogether (even though Joseph was basically Gran). Over several evenings I immersed myself in the passion and the brutality, the obsessive revenge, the jealousy and the violence of a story about a girl called Cathy that took place largely in a Northern kitchen. Mum recalled me finishing the book, turning to the front, reading the introduction, asking ‘What’s incest?’ (pronounced in-kest), getting no answer and starting the book again. This was a wild world where life and death were close to each other; where it was better to commune with somebody even if they were dead than not commune with them at all.

Elizabeth, Tricia and I attended a Church of England primary school and we regularly went to Sunday school at the village church. Sunday school mainly consisted of Mr Herbert, the vicar (or ‘parson’ as my father called him), reminiscing about being bombed in Coventry during the Second World War and did not seem to have much to do with God – or at least did not address the interesting questions like did God really look like Old Jack and where, exactly, was heaven.

As a child I did not think to question the existence of God and took comfort in both the idea of a Gentle Jesus Meek and Mild Looking Upon this Little Child, and the vague notion of a heaven – which, I supposed, hovered somewhere or other full of all the dead people and animals I had ever known. At Christmas, God and Father Christmas became rolled into one – a jolly-faced old man who knew exactly what you’d been up to. The Father Christmas version of God was more worrying than normal-God because he could punish you by failing to bring the selection boxes, talc and bath-cube sets and embroidered hankies that appeared under the tree every year.

My Aunty Dorothy gave me a white King James Bible when I was confirmed aged ten which contained photographs of the Holy Land; of barren rocks, entitled In the Wilderness, and silhouettes in a boat upon sparkling water, called Fishermen on the Sea of Galilee – photographs I half-believed were taken in the time of Jesus Christ himself. There was also a ‘Births, Deaths and Marriages’ section for me to fill in. I was proud of my Bible and found it considerably more interesting than the Book of Common Prayer I received at the same time. I noticed there was a chapter in the Bible that was never mentioned at school or Sunday school – the Revelation of St John the Divine. I wondered if perhaps the vicar didn’t want to jump ahead and spoil the end of the story.

I asked my mother what it was like when we were dead. She said, ‘Ask Mr Herbert.’ Mr Herbert had white hair that stood on end and waved like a dandelion clock, he wore thick black-rimmed glasses and a dog collar and his hands shook. I once met him on the way back from a trip to the grocer’s. He was carrying a wicker basket in which a lone half-sized tin of spaghetti hoops in tomato sauce rolled forlornly back and forth.

Mr Herbert came to school every Friday to tell us a story from the Bible but he did not engage in casual conversation with the pupils so I did not feel able to ask him anything. Instead I made up my own idea of heaven and decided heaven was a party in the village hall. I pictured the wooden chairs lined up around the edge of the dance floor, George the disc jockey getting his records ready, unseen ladies in the kitchen cutting sandwiches, arranging slices of Battenberg cake and over-diluting orange juice, the coloured lights glowing and the disco ball throwing sparkles hither and thither as it gently rotated – just like before the annual children’s WI Christmas party, in fact. But, this being heaven, it was a party only for the dead. Early doors Old Jack was there by himself but by the end of the 1970s all the empty spaces on the ‘Deaths’ page in my Bible were complete and the party was in full swing.

One night lying in bed in our freezing bedroom I asked Elizabeth whereabouts in the sky this heaven might be and she said, ‘Guess.’ I pointed up into the blackness somewhere over the milking parlour. ‘Nope,’ she said, pointing over the back garden towards the hen cabins, ‘other way! I win! That means you’ve got to get out of bed to put the light out!’

As a child there were a lot of people in my world and many of them were old.

I remember the moment I realized not everyone lived a life like mine, not everyone lived on a farm or even in a village. I was three or four years old and standing on the pavement in the local town waiting for the Whit Monday parade. Crowds two or three deep waited for the marching bands, the floats covered in crêpe paper and the festival queens with their retinues from all the surrounding villages – but I faced away from the road and stared at the toy-town houses behind me. I could tell they were tiny even though my head barely reached the door handles.

These houses were not like farmhouses; their front doors opened onto a pavement not a garden path or a farmyard, they had windowsills that I – somebody who didn’t even live there – could sit on, and they had windowpanes that I could press my forehead against and see right through. I stared harder. Yes, I could definitely see somebody’s ornaments and their settee and their fireplace.

Everybody I knew lived on a farm, usually down a long lane, surrounded by fields and woods and ponds and a yard and a garden and an orchard. Nobody could sit on our windowsills or look through our windows at our ornaments or our settees or our fireplaces.

‘Turn round,’ my mother said. I didn’t. I kept staring. Were these houses for old people, people who couldn’t walk and who sat in armchairs all day, like Old Jack? They couldn’t be for children, surely; not children like me and my sisters and my gaggle of cousins who could run as hard as we liked for as long as we liked and still not reach the neighbours.

I couldn’t believe how unlucky other children were not to have their own farms. All my relations had farms and each family was known by the name of their farm: ‘Sharples are here!’ ‘Crookhey have landed up!’

Each farm was popular for a different reason. ‘Sharples’ had a wood, ‘Crookhey’ had a pony, ‘High House’ had a brook, ‘Hookcliffe’ had a mountain, ‘Throstle Nest’ had a grassed-over gravel pit, ‘New House’ (us) had a great stone barn with the world’s best rope swing and an old hen cabin filled with discarded furniture – tables and chairs riddled with woodworm, cupboards with warped doors that wouldn’t open and then wouldn’t shut again, an old camp bed with creaky springs, and everything coated in dust – which was the best den in the world. Farms were chock-a-block with hiding places and climbing trees and animals and it was easy to escape the adults while you created whatever world you wanted, but the people who lived in these houses, these tiny houses right beside the pavement, apparently all sat together in cramped little spaces, with strangers staring at them through the window.

Despite having so many cousins, my sisters and I were thrown together a lot without the company of other children. I knew I was lucky to have Tricia from very early on.

I was maybe six years old. It was dinner-time (the meal we ate at midday). We had set places at the kitchen table: Dad at the head, me and Tricia with our backs to the lumpy Artex wall, Elizabeth and Mum with their backs to the kitchen fire, Mum near the cooker, and Gran at the bottom. On this day I was upset and left the table – did I ask for permission? I don’t remember – but asking for permission was considered important in our family. Please may I leave the table? Table manners were some of the few rules I remember my parents explicitly teaching us – presumably so other people would think we’d been brought up right.

Don’t put your elbows on the table; Don’t talk with your mouth full; Always put your knife and fork together when you have finished; Never lean in front of other people; Don’t scrape your knife on your plate; God forbid don’t lick your knife; Don’t say ‘God Forbid’; and always chew with your mouth closed.

I was once sent away from the table for laughing.

I can’t remember what upset me on this particular day but I left my place and curled into a ball on the living-room carpet, forehead pressed to knees, crying. I heard Mum and Dad laugh and I looked up. Next to me Tricia – only a toddler at the time – had curled into an identical ball to keep me company. I sat up, my face wet and cold with tears and with bits of dust stuck to it from the carpet. Tricia sat up too and looked at me with her solemn brown eyes. I of course did not know the word ‘empathy’ but I thought: Tricia is here. Tricia is with me. Tricia understands. Tricia is the one who loves me.

Tricia was the most loving and lovable child, so sweet-natured it was easy to take advantage of her. She was cooperative and eager to please – not in a needy way but in a happy way.

Elizabeth and I were good at giving her orders: get this, get that, fetch this, fetch that, go for this, go for that, play this, play that, watch this, watch that. I made her play ‘Schools’ before she knew what a school was and had no idea about bells and desks and lessons, and stared at me baffled as I kept ringing an imaginary bell in her face expecting her to line up for playtime. I made her play ‘Hospitals’ when she was small enough to be crammed into the dolls’ cot and be fed ‘medicine’ of sugar and water. She wasn’t keen on the sugar and water but she wanted to play so much she went along with it. Tricia was always game – we’d realized that when she suddenly stood up and walked at nine months old.

Inevitably, as two’s company and three’s a crowd, Elizabeth and I fought over Tricia and, with me being younger than Elizabeth, I often lost. When all three of us played ‘Houses’ in the old hen cabin, Elizabeth was ‘mother’ in the best cabin with all the best junk furniture and Tricia was her baby while I got to live in the rubbish cabin (the cabin next door filled with logs and chicken wire) and be the nasty neighbour, Mrs Crab-Apple.

Me, Elizabeth and Tricia, centre front, at the WI Christmas party – my idea of heaven

I liked to get Tricia to myself and on Tuesday evenings, when Elizabeth went off in the car with Mum for her piano lesson, Tricia and I had our own game to play: ‘Hiding from the Germans’. This entailed dashing around the farm from one hiding place or vantage point to another – from among the hay bales in the loft to the back of Gran’s Dairy, from behind the dog kennel (a metal barrel on its side) to the top of the great stone cheese presses in the farmyard we sprinted here and there, flinging ourselves onto our bellies, ‘Ssssh! Keep your head down. Keep quiet!’ as we tried to evade capture and spot the enemy before they spotted us. As a rule we were not a film-watching family and nobody bar Mr Herbert, the vicar, talked about the war (although this was only twenty-five years after the end of the Second World War) so I can only think this game stemmed from watching The Guns of Navarone or The Great Escape or something similar in the sitting room with Uncle George one Christmas Day.

The farm provided great reading hideaways – up trees, on roofs, inside a stack of straw bales with a torch, where I’d read and itch and sneeze. I enjoyed finding a hidden place to escape into a book. Unseen among the branches of a tree or high up on a building I’d watch and think and feel safe. I always knew if Dad or Gran were near by the rattle of buckets.

At other times I’d lie on the back lawn staring into the sky at the white vapour trails from Manchester Airport. Sometimes the longing to be on board a flight was so strong it was an out-of-body experience. It didn’t matter where it was going, anywhere was better than here. Second only to flying away was the dream of a road trip. I watched wagon drivers jealously when they visited the farm, imagining the freedom of the road. Sometimes they’d turn up with a girlfriend slumped in the passenger seat looking bored, chewing gum with her bare feet up on the dashboard among the toffee wrappers and under the rabbit’s foot dangling from the rear-view mirror, and I’d know those girls were truly blessed.

Freedom for me meant wearing no shoes. My sisters and I were never bothered by dirt and as we ran about the farm I never wore shoes, just socks, and I could leap from one dry patch to another, from one clean, flat stone to the next, avoiding mucky puddles and nettles and sharp stones. For many years I half-believed I could fly, just a little, if I willed it hard enough. That is the sort of thing I told Tricia; that I could fly and that she could too if she tried hard enough; if she ran fast enough and didn’t breathe and only touched the ground with her very tippy toes she would fly. I can see her face now as she drank it in, solemn-eyed, amazed but believing it, believing every word I said.