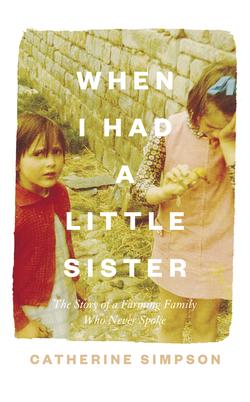

Читать книгу When I Had a Little Sister: The Story of a Farming Family Who Never Spoke - Catherine Simpson, Catherine Simpson - Страница 12

Chapter Five

ОглавлениеAfter Tricia died the thought of what would be involved in clearing the farmhouse was terrifying.

A few years earlier I had viewed a house for sale in which the owner had died of a heart attack only days before and I had been appalled to see bread on the kitchen units that was still in date and the dead owner’s appointments on the calendar for the following week: Coffee with Bernard, 2 o’clock.

Families move at different speeds. Tricia had been dead six months when Dad said, ‘What about doing something wi’ yon house?’ and we knew we couldn’t put it off any longer. At first I thought we’d get a skip, but no, Dad built another enormous bonfire in the orchard – this time away from the telephone wires – and, bit by bit, we ferried generations of possessions onto what was in effect a funeral pyre.

Not knowing what to do with many things with sentimental value, we threw them into a ‘Memory Box’, actually a yellow cardboard box in which my new boots had just arrived.

These were the things we saved:

Tricia’s childhood jewellery: tangled silver chains, little charms and bent and twisted earrings; her drawings and paintings, watercolours of cats and dogs and horses and self-portraits; photographs of Tricia with friends we didn’t know in places we didn’t recognize. I studied her face, scanning her expression for signs of distress – did she want to be there? Was she enjoying herself or was she desperate to be alone, smoking? Was that a false smile? Was she suffering? Was that one of her good days or one of her bad?

We saved stacks of her notebooks and diaries that I couldn’t bear to read – including the notebook that the police officer had removed along with her body. ‘She wrote a lot, didn’t she?’ he said the following day when he returned to take down more details. Elizabeth was angry. We did not know what she’d written in that notebook so why should he? Apparently, though, the book did not shed any light on her thoughts on her last night on this earth – it did not contain a suicide note. We were allowed to have it back after the inquest, except by then it was lost. Incensed they had been so careless with her things, we asked the Coroner’s Office to chase it up until the police found it and hand-delivered it to Dad’s in a sealed envelope to stop him reading it and getting upset.

We saved Tricia’s soft toys. How do you burn a teddy bear you remember from childhood, no matter how filthy? We saved a home-made sheep, a rock-hard badger and a gangly Pink Panther. Who made these? Nobody could remember. It was probably Mum’s mum, Grandma Mary, who took up handicrafts with a passion after her husband, Grandad Ben, died – sublimating her grief in patchwork dogs, hessian dolls and punched leather work.

We saved Tricia’s one-legged Tiny Tears doll called Karen who we found naked except for a bikini drawn on in green felt pen and wrapped in Mum’s old fox fur with its flat nose and glass eye. Karen and the toys were rescued from the farmhouse only to be flung on a rocking chair in a corner of Dad’s house where they remain, described by my teenage daughter, Lara, as ‘that pile of old weird shit’.

We saved sherry glasses – stacks of sherry glasses in styles ranging from the delicately etched of the 1930s to the clunky and chunky of the 1970s – even though we had never drunk sherry except at Christmas. Where had all these sherry glasses come from? Dead great-aunts? Grandma? No one could remember but we took to drinking Harveys Bristol Cream before supper.

I saved a page of doodles I discovered with the words ‘My name is Nina, and I am brilliant and I must not forget it’ written on, surrounded by trees and hearts, shoes and cats. I framed it and hung it on my daughter, Nina’s, wall.

Although many items had been removed in the weeks after Tricia died, there were still plenty of things dangling in the wardrobe. I saved clothes that would never fit me and would never be worn again even if they did but that I remembered Tricia wearing, including the twenty-year-old bridesmaid’s dress she wore at my wedding. We saved a flowery skirt that I turned into a cushion, a dress I turned into a jumper and a jumper I turned into a hat. We saved broken beads to be made into Christmas decorations. We saved her piano certificates. We saved her swimming badges, from 50 metres to bronze lifesaving, which were still attached to her red stripy swimsuit. Going to ‘the baths’ at Lancaster had been a big deal. The first time we went I must have been about seven and expected it to be one big claw-foot bath like we had at home. I wore a swimsuit with polystyrene floats fitted round the waist – a costume rejected by Tricia. I gazed, fascinated, at the sign NO RUNNING, PUSHING, SHOUTING, DUCKING, PETTING, BOMBING, SMOKING with its helpful cartoon illustrations and I clung to the side as Tricia set off on tiptoe, splashing across the shallow end seemingly unconcerned by water lapping at her nostrils. It was similar to the only time we went ice skating. Then I’d gripped the safety rail while Tricia’s game spirit was spotted by a stranger – a middle-aged woman – who led her around the rink. By the end of a torturous hour for me they glided serenely back, side by side with crossed hands, like something off a Victorian Christmas card. Tricia was always braver than me.

Some things were easy to burn: the piles of medication in blister packs, which went straight on the bonfire, as did stacks of appointment letters from the mental-health services. We burned her last packet of fags – the pack of ten with the four missing that we found on the bathroom floor – but by then I regretted we hadn’t put these with her in the coffin. Tobacco had been a good friend to Tricia.

Many things were hard to burn; for instance her socks. Cello cried as he emptied her sock drawer onto the bonfire and watched Dad stopping the balled-up socks from rolling out of the flames with his big stick.

Sometimes we got cavalier. I tossed a toilet bag into the fire without checking carefully enough what was inside, only to discover too late that it contained aerosols and sealed tubes that exploded and sent my father diving for cover behind the giant bamboo.

During the weekends of clearing, the flames burned bright throughout Saturday afternoon and if they began to flag Dad would douse them in diesel and they’d soon be ten feet high again. The bonfire would still be smouldering on Sunday morning which meant we could continue; sofas, mattresses, damp quilts and bedspreads, all the velvet curtains, carpets, lino, on they went.

It felt cleansing and became addictive; you’d find your eyes scanning a room for flammable materials. A battered screen! Dried-flower arrangements! More wool! Let’s drag them out and burn them!

Once the rooms were empty we started pulling off wallpaper that hung loose and damp in places – great lengths of woodchip painted in shiny turquoise and mauve that came away bringing layers of plaster with it. We’d bang the flaking plaster with a brush until it all fell and we had at last got back to a sound surface. We wrenched off sheets of plasterboard that had been used to box in original features in the 1970s, to reveal wallpaper from the 1950s with hand-painted roses and lily of the valley.

To watch dusty, neglected, largely unloved items set alight, burn, smoulder and turn to ashes felt right. It also felt very warm and, despite it being summer when we did the clearing, the heat on my face was comforting and gazing into the heart of a fire consuming my family history was mesmerizing.

As a seven-year-old, I had watched the disposal of my Great-Great-Aunt Alice’s things and been fascinated by the dismantling of a life, fascinated to see someone’s life story being taken apart into its bits and pieces and each one being held up to the light, valued in some way, then kept or discarded.

There were legends about Great-Great-Aunt Alice: she was a suffragette; she founded her own bus company between Manchester and Blackpool; she was a ‘man-hater’ who married a much younger man only to pay for him to go to Australia and never come back. It was said she was so tight with money she reused old stamps. She was a hoarder whose bungalow was only navigable via narrow corridors between the piles of junk. She nearly killed herself by keeping warm with an electric fire placed on the bed because there was nowhere else to put it and which then set the bedding alight; and, as recalled by one uncle, ‘she had a dirty parrot who shit everywhere’.

But you only heard these legends if you asked, because Great-Great-Aunt Alice had no children and so when she died she began to fade fast into history.

Great-Great-Aunt Alice: suffragette, businesswoman and hoarder

I have her photograph on my living-room wall in my gallery of ancestors. The picture dates from around 1914 when she was in her mid-twenties. She is wearing a high-necked Edwardian blouse and two thick gold chains with pendants of amethyst and quartz. She has a cameo brooch pinned on one side and a gold nurse’s-style watch on the other. Her hair is swept up into a chignon and she stares past the camera with a determined expression. She is clearly a woman who amounted to something.

When I was six or seven she was very old and dying and she came to stay for a few weeks with Grandma Mary. Mum and I went upstairs to take her a bowl of prunes on a tray. The air hung heavy in the bedroom where Great-Great-Aunt Alice was a small hump under the bobbly candlewick counterpane. Her little grey head turned as we entered.

She struggled to get her tiny shoulders up onto the pillow so she could taste the prunes in their sticky brown juice. The spoon shook in her hand and clacked against the rim of the bowl and dribbles of juice trickled down her chin. In a loud and forced-cheery voice Mum said, ‘We’ve come to have a look at you,’ which was the usual greeting in our family, but Great-Great-Aunt Alice said nothing; all her fading energy was concentrated on getting the prunes onto the spoon and up into her toothless mouth.

Being so infirm, taking so much effort to raise a spoon to your mouth, and to suck and to swallow, to not be able to talk, to want to eat prunes at all – this looked to me like somewhere between life and death, but nearer to death.

A week or two later we went to Grandma Mary’s for the usual Sunday afternoon visit and Great-Great-Aunt Alice was nowhere to be seen. Instead there were Great-Great-Aunt Alice’s things; boxes and boxes of shoes and handbags and petticoats, so many things that the big farmhouse kitchen was like a jumble sale. I particularly remember the petticoats in satin and silk and watching Tricia and Cousin Elaine clop past wearing one each, lifting them up like Cinderella’s ball gowns as they clattered and wobbled by in Great-Great-Aunt Alice’s shoes. There was a reek of mothballs.

One of my uncles held up a great pair of white bloomers and said, ‘Run them up a flagpole and folks’ll know you’ve surrendered,’ and everybody laughed.

We poked through drawers that had been removed from chests and dressing tables, which must have been brought from Great-Great-Aunt Alice’s bungalow after her death and dumped on Grandma Mary’s kitchen table. They were filled with the usual stuff that accumulates in drawers: dried-out pens, purses with the odd sixpence inside, bottles gummed up with the residue of sticky yellow cologne, tickets for long-forgotten trips, postcards from long-lost friends. In the grime in the corner of one drawer an aunt found a garnet and seed-pearl ring and trilled, ‘Is it finders keepers?’ Grandma, who was standing at the kitchen unit slicing boiled eggs for tea with a plastic and wire contraption, didn’t look round and said, ‘Take what you want.’

I left with a bracelet of coloured stones and an evening bag all silky inside and infused with a lingering scent of a long-ago perfume. I was delighted to own such glamorous things, and, as both the bracelet and the bag were considered rubbish by my mother, I was at liberty to drag them around the farmyard with me until both the bag and the bracelet were broken and lost.

Many years after the disposal of my Great-Great-Aunt’s things I read Mrs Gaskell’s Cranford. In it Miss Matty burns her parents’ love letters.

‘We must burn them, I think,’ said Miss Matty, looking doubtfully at me. ‘No one will care for them when I am gone.’ And one by one she dropped them into the middle of the fire, watching each blaze up, die out, and rise away, in faint, white, ghostly semblance, up the chimney, before she gave another to the same fate.

I ask myself now: is it possible to dispose of a person’s effects with dignity?

Some months after writing this I discussed these memories with my Cousin Mary. She remembered all the stories of Great-Great-Aunt Alice; yes, she did indeed buy her husband a one-way ticket to Australia, writing ‘liar, thief and all that is bad’ on the back of his remaining photograph. And yes she was a suffragette and made money in stocks and shares and in business, and tried to keep warm by putting the electric fire on the bed – and she did set the bed on fire. But here my memory proved faulty. The bed-fire had in fact killed Great-Great-Aunt Alice after a short hospital stay. So who was the tiny grey-haired lady eating prunes whose stuff we had shared out? It turned out to be another unmarried, childless great-great-aunt called Annie. And this underlined for me that after death not only do we disappear and our belongings become scattered, but our stories begin to blend with the stories of others and meld and shapeshift like a flock of murmurating starlings.

A few years after Great-Great-Aunt Alice (or, as it now seems, Annie) died, my Great-Aunty Margaret died too, also leaving no children, so the contents of her seaside bungalow went up for public auction. I had moved away by then and didn’t go and afterwards I asked Mum what had happened to Great-Aunty Margaret’s most prized possession – her silver epergne, an elaborate candelabra centrepiece that she displayed on her sideboard, proudly telling everyone it had once belonged to Rochdale Town Hall. My mother said, ‘She’d polished it so much she’d worn the silver plate off.’ She shrugged. ‘Somebody must have bought it, I suppose.’

Great-Aunty Margaret suffered from dementia and as it progressed she told us the same stories over and over again. The one she recounted most often was how she got up on her twelfth birthday to be told she was never returning to school and there was a job waiting for her in a Rochdale cotton mill. ‘I did cry,’ she repeated. ‘Oh, I did cry.’ She spent the last months of her life in a home. Her upright piano, and the sheet music for ‘I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles’ and ‘I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now’, went to the home with her in the hope she would play for the other residents. On arrival she declared she had never set eyes on that piano before and it most certainly was not hers. She never touched it again.

Great Aunty Margaret left school at 12 to work in the cotton mill

Some of Great-Aunty Margaret’s more personal effects, which in her handwritten, home-made will she had earmarked for particular old friends, were brought to our farm in a black bin liner for my mother to distribute. They included her fur three-quarter-length, her astrakhan coat and her engagement ring – a small flower set with diamonds.

My mother dumped the bag in Gran’s Dairy – I don’t know why, the farmhouse was big enough for umpteen bin bags – and my father mistakenly, but inevitably, dragged it out for the bin men. Within days it was flung in the dustcart and that was the end of Great-Aunty Margaret’s legacy. Mum and Dad made a mad dash to the council tip at Fleetwood to try to retrieve the bag of Great-Aunty Margaret’s treasures but arrived to find a sea of similar black plastic bags stretching to the horizon and realized the furs and diamonds were gone for ever.

As a young woman Great-Aunty Margaret had wanted a family. There was a story that she once thought she was having a baby. She got fat. She made preparations. Unfortunately she stayed pregnant for more than nine months, at which point the phantom baby faded away.

We emptied the farmhouse over many weekends during spring and summer, 2014.

It was filthy, dusty work. I dug through the dead weight of Tricia’s vinyl records and found a Roy Wood album from forty years ago and played it at full blast. ‘Look Thru the Eyes of a Fool’ crackled and slurred and jumped and blurred under the blunt needle and vibrated the stagnant air in the house just a little. As fire was cleansing, so was noise.

I found a load of washing Tricia had done months before still in the machine mouldy and rotting and loaded it straight into a bin bag.

I took photographs to remember the things we burned and to feel I was keeping a part of them: the fusty Disney picture books of Cinderella and Bambi and Alice in Wonderland from the 1970s, the disintegrating 1950s Vogue pattern for evening gloves, the handbook for a 1960s wringer, a 3d pattern for a crocheted hat that would ‘only take one hour to make’, hard-backed books with titles like Ezra the Mormon and The Major’s Candlesticks, rotting, mildewed Sunday-school prizes signed in fading ink and in a formal script ‘for Stuart, for regular attendance, 1934’. From under the stairs we dragged out half-made rag rugs from the 1950s and a romantic print of a Regency couple marked on the back ‘Christmas 1908’.

Growing up surrounded by all this lingering stuff, with the past and the present and the living and the dead tangled and colliding, it’s hardly surprising that as a child I looked out of my bedroom window and glimpsed Grandma Marjorie, dead since 1938, carrying a basket of washing across the back yard.

By taking photographs of what we were removing, I believed I was in some way keeping the spirit of the thing. It was unthinkable that I should forget. What if I suddenly needed to know the exact shade of blue of Grandma Mary’s old beaded evening gown? The one she wore in the 1970s to meet the Queen. Was it sky blue or was it nearer royal blue? Or what if it was important to recall the precise swirling pattern on the sitting-room carpet? The carpet that was being fitted when half our feral cats climbed in the back of the fitter’s van and were driven off and lost for ever.

I took photographs of Dad’s mummified football boots which had hung on the garage wall for seventy years, of the view from every window, of the texture of the brickwork, the rust on the outhouse window locks, of the flaking paint on the barn door, of the weeds sprouting between the cobbles and the ivy coiling round the fence posts. Turning these story fragments and half-memories into photographs meant the past was not completely lost nor the memories obliterated. All these things were part of our lives here and might in some small way explain how that story ended as it did.

Me and Dad, discovering Ezra the Mormon and The Major’s Candlesticks

I snapped away and heard Lara whisper to Cello, ‘Mum’s just taken a photo of the ground.’

If things could be saved – if they weren’t stinking of mould or half-eaten by moths – we sometimes packed whatever it was into a box and dumped it in Dad’s garage to create a whole new problem for another day, saying to ourselves, ‘Well, you never know.’

I framed a certificate I discovered in the sealed-up cupboard halfway up the stairs that still housed Aunty Marjorie’s Sue Barton books, the paint on the cupboard doors finally cracking from top to bottom as I wrenched them fully open. The certificate was from the Ministry of Agriculture’s ‘1944 Victory Churn Contest’ and had been awarded to the ‘farmers and farm labourers of New House Farm’ for increasing the farm’s milk yield by over 10 per cent during the country’s ‘time of need’.

I took tarnished silver spoons home to Scotland and polished them until they shone, only to let them blacken again without using them. I put the headless dressmaker’s dummy, still set to Mum’s exact measurements, to stand vigil in Dad’s spare bedroom. I gathered stacks of photographs of unnamed, unknown people and tried to persuade aunts and cousins to identify them and take them away, largely without success. Some were marked but the markings left more questions than answers; on the back of one black and white photograph of a man in a suit and spectacles and bowler hat who looked like a bank manager, written in Grandma Mary’s hand was ‘Uncle Percy; cut his throat on a park bench’, or another of a woman in a 1930s dress, written in an unknown hand: ‘My mother.’ When I asked around about ‘Uncle Percy’, no one seemed to know.

As Mum had not liked sharing her things, she had been equally unwilling to share information. Family anecdotes were treated like state secrets and any request for details was greeted with tight lips and a Stop mithering or a What do you want to know THAT for? Telling stories was ‘gossiping’, even if the people involved had been dead for a generation – which meant stacks of photographs were left untethered from their stories.

There was a white box of wedding photographs showing my mother and father on the day they married in 1959; my mother beautiful without make-up and in a home-made dress – a lace and duchesse satin creation that could have come from a couture house. A dress I was disappointed as a child to discover she had chopped up to make satin cot quilts for us as babies – a decision that I now see makes perfect sense. In the black and white wedding photographs my father is handsome in a bespoke suit and white carnation and, in some, with what must be a bright red ‘L for Learner’ sign pinned to his back by my mother’s brothers.

As a child I would have revelled in the glamour of these photographs and listened rapt to the details of the day, but those details were never divulged by my mother who kept the pictures out of sight at the bottom of the wardrobe with stacks of wool and material on top. We’d get tantalizing glimpses of the white box but were strictly forbidden to ‘root’. And now it was too late. Now my mother’s memories of the day were lost for ever. My mother wasted an opportunity to talk and to share and it still makes me mad with her, even though she has been dead ten years. What was the point of having these photographs at all if they were to be abandoned to moulder out of sight?

Mum and Dad married in 1959

By contrast my father keeps the brochure for their honeymoon in his desk drawer. He takes out the small blue booklet, Cook’s Motor Coach Tour to the Sunny French and Italian Rivieras, Taking in London, Grenoble, Nice, Monte Carlo, San Remo and Paris, at every opportunity to tell us again about the casino in Monte Carlo and the ‘Paris by Night’ coach tour on the way home. This must have been quite some tour in 1959; the brochure’s instructions hint at the novelty of the trip: ‘It is not practice for hotels to provide toilet soap and it is recommended that you take your own soap and at least one hand towel … Cameras can be taken on the Continent, and films purchased quite easily … As there may be opportunities for bathing you may wish to pack a bathing suit … Sunglasses will add to your comfort … Baths (unless you have booked a room with private bath at a supplementary charge) and afternoon teas are not included.’ Torquay or, God forbid, Blackpool would not have done for my mother, but whenever Dad talked about their glamorous trip she’d respond with a dismissive wave of the hand. Who wants to know about that?

When we were left with only heavy furniture in the farmhouse we called a house clearance cum antique dealer who sent along a pair of rough-looking blokes called Pete and Trev. Pete and Trev pulled up outside with a van already packed, and with no apologies for being two hours late. The things we wanted them to take included the enormous bedroom suite my father’s parents, David and Marjorie, had arrived with in 1925 as newly-weds. This suite was heavyset mahogany elaborately carved with leaves and flowers and smelling of camphor. There were four pieces: a wardrobe with an arched bevelled mirror, a marble-topped washstand, a dressing table and a bedside cupboard with a shelf for a chamber pot.

As Pete and Trev sauntered about the farmhouse their eyes never looked where we pointed but flickered around each room, alighting briefly on everything else. Furniture was touched, smoothed, handled, turned upside down, and pronounced upon with a shaking head. ‘Brown furniture, you can hardly give it away these days,’ said Pete or Trev. ‘It’s all IKEA now.’ Pete or Trev grimaced. ‘A piano? It’d cost me more to take it than to leave it. The last one – I couldn’t give it away – had to get it dropped from a crane to break it up.’ Cupboard doors were opened and shut; drawers were slid in and out, out and in, removed, twizzled round. ‘Where are the drawers for this Georgian chest?’ asked Pete or Trev. Unfortunately the answer was ‘on the bonfire’. ‘Where is the other table from this G Plan nest?’ We looked at each other; maybe our eyes flickered to the window with the view of the bonfire. Nest? Was there another table as ugly as that one? Eventually Pete or Trev brought out a roll of banknotes from a trouser pocket and rapidly peeled off several. ‘Three-fifty and it’s off yer hands.’

There was almost a hysteria by now about finishing this task which had been generations in the making. The decisions we made were hasty and getting hastier because Elizabeth and I lived hundreds of miles apart and so we did the job in bursts at weekends. It felt at times as though we would never get to the end of it. I had the sensation of trying to free myself from a sticky cobweb that clung relentlessly, refusing to let go and entangling me further no matter how hard I grappled.

Not long after Pete or Trev paid us for the bedroom furniture we found a list of wedding presents, handwritten by Marjorie in 1925, headed up ‘Walnut Bedroom Suite – given by Mother and Father’. So it was walnut not mahogany. I felt a guilty stabbing – what were we doing? – before common sense reasserted itself.

As the house became emptier and brighter it seemed physically to lighten and relax. When David and Marjorie’s enormous bedroom suite was finally removed by Pete and Trev ninety years after it arrived, it was as though the house had lost its anchor or had its roots severed. The farmhouse was now empty and echoing and it seemed there was every chance that, unencumbered by our family detritus, I might return to it one day and find it had gone – that it had floated entirely away.