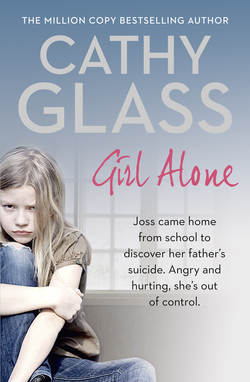

Читать книгу Girl Alone: Joss came home from school to discover her father’s suicide. Angry and hurting, she’s out of control. - Cathy Glass, Cathy Glass - Страница 11

Chapter Six Deceived

ОглавлениеThe following afternoon I received a telephone call from Joss’s form teacher, Miss Pryce. She apologized for not being in touch sooner, she’d been very busy, and she invited me to go into school to meet her the next day at 12.30 p.m.

‘I’m afraid my lunch hour is the only time I have free,’ she said.

I thanked her, confirmed I’d be there and felt marginally guilty for taking up her lunch break.

When Joss arrived home from school that afternoon I told her I was seeing her teacher the following day. ‘So I hope she’s going to tell me lots of good things about how well you’ve been doing,’ I said. ‘And that all your homework is up to date.’

‘I doubt it,’ Joss said with her usual shrug.

‘Well, in that case you need to do your homework before you go out this evening. That’s what the contract of behaviour says.’

‘I haven’t signed the contract yet,’ Joss said, ready with a retort as always. ‘Anyway, my homework is up to date.’

I wasn’t convinced this was true, but I would wait until I’d heard what Miss Pryce had to say before I said anything further to Joss about her school work.

The atmosphere at dinner that evening was less strained than it had been during the last few meals, after Lucy and Joss’s set-to – they made an effort to speak to each other, while Paula and Adrian kept a low profile and concentrated on eating. As soon as Joss had finished her pudding she stood to leave.

‘Joss, would you remain at the table, please, until everyone has finished,’ I said. ‘It’s polite.’

‘Do I have to?’ she grumbled. ‘You sound like my mum.’

‘Yes, please. It’s only six-twenty; you’ve still got plenty of time to go out.’

She pulled a face but did as I asked, and sat down and waited until we’d all finished.

‘Done?’ she asked as Paula, the last to finish, set her spoon in her bowl.

‘Yes, thank you,’ I said. ‘You can go now.’

Joss took her dishes to the kitchen sink, then went into the hall, put on her shoes and called goodbye as she left.

I am sorry to say that I always felt more relaxed when Joss was out of the house, as I never knew when she would erupt in another angry outburst or confrontation. Although, of course, when she was out I also worried – about the mischief she could be getting up to and whether she was safe. I was expecting her to return home late – she hadn’t managed to return on time after an evening out with her friends yet – and if she did I would be stopping one pound from her pocket money (the one pound she’d earned back for coming home on time the previous afternoon). She would still have half her allowance, as Amelia had stipulated she should. However, to my surprise and delight, she returned at exactly 9.30 p.m.

‘Well done, good girl,’ I said. ‘I am pleased.’

‘Can I have a door key now, as I’m back on time?’ she asked.

‘Not yet, love. “One swallow doesn’t make a summer.”’

She looked at me slightly oddly, and slipped off her shoes.

‘You’re working towards it,’ I said. ‘A couple of weeks of coming home on time and then we’ll see.’

‘What’s a couple?’ she asked.

‘Two.’

She pulled a face. ‘I can’t do that,’ she said. ‘Two weeks is far too long. I’m not an angel.’

I had to smile. She had a dry sense of humour sometimes. ‘Joss, you’ve come home on time tonight, as you did yesterday afternoon, so there is no reason why you can’t do it again, and again.’

‘I had a lift tonight,’ she said.

‘From Chloe’s mother?’

‘Her uncle.’

‘I trust he hasn’t been drinking too?’ I could smell alcohol on Joss’s breath, although she wasn’t drunk.

‘Only one. He’s sensible,’ she said.

She said she wanted a glass of water and went into the kitchen. I wandered in too.

‘Was Chloe in the car with you as well?’ I asked casually.

‘I think so,’ she said as she took a glass from the cabinet.

‘You must know, love.’

‘Yeah, she was.’ Joss concentrated on filling her glass from the cold-water tap.

I looked at her carefully. ‘Joss, I’m only trying to protect you and keep you safe. I care about you, and while you’re with me I’m responsible for you.’

‘Yeah, I know, you said. Thanks. It’s much appreciated,’ she said dismissively.

She switched off the tap, said goodnight and went upstairs to bed. Joss’s hostility and constant rebuffs were without doubt a defence mechanism – to stop others from getting close. The logic behind this is that if you don’t form an attachment, with the possibility of losing that person, then you won’t be hurt again. Only, of course, it doesn’t work like that, and one of the scariest places to be is a teenager isolated, alone and suffering in silence.

The following day, at 12.15 p.m., I parked my car in a side road close to Joss’s school and made my way round to the main front entrance. The weather was warm and the students were allowed off the school premises during lunch break. I passed small groups of kids chatting and laughing and also smoking quite openly, although out of sight of the main building. I thought it was a great pity that so many young people still thought smoking was cool and hadn’t got the message that it was damaging their health. The school was in the older part of town and didn’t have the best reputation. From what I’d heard and read in the local newspaper, the standard of teaching was reasonable, but there were ongoing concerns about discipline and the students’ behaviour, both inside and outside the school. Shopkeepers in the area complained about pilfering, and residents said that gangs of students roamed the streets after school, graffitiing fences and walls, throwing rubbish into gardens and bad-mouthing anyone who came out to complain.

I went in through the main doors and gave my name to the receptionist, explaining that I had an appointment with Miss Pryce at 12.30. She said she’d let her know I was here and asked me to sign in the visitors’ book and take a seat in the waiting area, which was over to the left. The corridors were noisy at lunchtime with students milling around. They wandered past me in pairs and small groups on their way outside. Many of the girls wore their skirts very short, as Joss did, with knee-length socks, which were fashionable. Both girls and boys had their ties loosened, or weren’t wearing them at all, and some had multiple ear piercings, as Joss did. Presently, Miss Pryce appeared. She introduced herself – ‘Lisa Pryce’ – and then led the way down a corridor and into a room on the right.

‘We shouldn’t be disturbed in here. Do sit down,’ she said, waving to the four chairs that stood around a small table in the centre of the room. A photocopier, filing cabinets and cupboards stood against the walls.

‘Thank you for making the time to see me,’ I said.

‘Not at all. It’s important we meet. I’m very worried about Joss, and all the moves haven’t helped. She won’t be moved again, will she?’

‘I hope not. But ultimately it will be for the social services to decide what is best for her in the long term.’

Miss Pryce tutted. I guessed she was in her mid-thirties, about five feet six inches tall, and her brown hair was cut in a neat bob. She was wearing a pale-blue summer dress. She would be aware of Joss’s past.

‘I feel very sorry for Joss,’ she said. ‘But that’s not going to help her achieve or get back on course. She’s like a runaway train at present, heading for disaster. Up until a year ago she was a grade-A pupil, but now she’s barely achieving Ds. Much of her work is unfinished or completely missing, so it is ungraded. Worryingly, Joss doesn’t seem to care. I have to treat all my students the same, and it’s no help to Joss if I just keep letting her off.’

‘No, indeed,’ I said. I’d immediately warmed to Miss Pryce’s direct, no-nonsense approach, and I formed the impression that she would be firm but fair with her pupils.

‘We’ve offered Joss counselling,’ she continued. ‘The school may not have the best academic results in the county, but we are a very caring school. Joss knows she can talk to the school counsellor, or me, or any other member of staff at any time, but she’s never taken up this offer. She’s often late for school, especially after lunch. As you probably saw, pupils are allowed off the premises during the lunch break, as long as they return on time. We’ve had instances of Joss returning late, with another girl, smelling of smoke and possibly under the influence of something – perhaps cannabis. She’s had one exclusion and she’s heading for another. If she continues like this she’ll be excluded permanently, which will mean more uncertainty for her and a move to a new school, possibly miles away. I know Joss’s mother, Linda, and I’ve met one of Joss’s previous foster carers, so I’m aware that her behaviour at home is causing great concern too. Joss is on a path of self-destruction and, to be honest, I’m at a loss to know how to help her. I’m sorry this all sounds so negative, but you need to know.’

I felt utterly deflated. ‘I knew things weren’t good at school,’ I said. ‘But I hadn’t realized they were this bad. Some children I’ve fostered have misbehaved at home but tried their best at school.’

‘Not with Joss, I’m afraid,’ Miss Pryce said. ‘She’s a capable girl, but she’s destroying any chance she has of achieving academically. I’m also worried about her on a personal level. I’m a mother and I’d be devastated if this was happening to my daughter. Who are the two men who collect her from school sometimes? Do you know?’

‘No, I don’t.’

‘They’ve been seen a number of times, waiting further up the road, at lunchtime and also after school. Members of staff have spotted Joss and Chelsea getting into their car.’

‘I didn’t know about any of this. Do the social services know?’

‘We informed them, but as far as I know no action has been taken. Although in fairness to them, what can they do? The car is parked on a public highway and they are not committing any offence. Both Joss and Chelsea were spoken to by a member of staff, but the girls were blasé and couldn’t see any danger. They insisted the lads were old friends. Perhaps they are.’

‘I don’t know,’ I said. ‘I’ll try to talk to Joss about this, but she’s not very communicative with me yet. I sanction her if she’s late in, and now I know she’s behind with her school work I’ll make sure she does it before she goes out.’

‘Thank you. It’s a pity she can’t find another friend. Chelsea has so many problems of her own.’

‘Who’s Chelsea?’ I asked. ‘I haven’t heard Joss mention her.’

Miss Pryce looked slightly surprised. ‘They spend all their time together. Chelsea is two years older than Joss, but they’re inseparable. If there’s trouble, you can be sure they’re in it together. A biggish girl with long black hair.’ I realized this sounded like Chloe.

‘And Chloe?’ I asked. ‘Is she part of their group?’

Miss Pryce frowned, puzzled. ‘No. Chloe who?’

‘I don’t know her surname. She’s in Joss’s class?’

‘There is a girl called Chloe in the class, but she and Joss aren’t friends. They don’t have anything to do with one another. Chloe is a quiet, shy child, very studious and hard-working. Her parents would never let her out to wander the streets with Joss or Chelsea.’

I felt the criticism personally. ‘You appreciate that, as a foster carer, I’m very limited in the sanctions I can impose on Joss. For example, I can’t stop her from going out if she wants to.’

‘I know. It’s ridiculous. We have other children in school who are in care, so I am aware of what foster carers can and can’t do. If these were our own kids, we’d lock them in the house if necessary to keep them safe.’

‘Exactly. I’m doing all I can to try to get Joss back on track, but it may take time. If you could inform me of any incidents at school, I’d be grateful. Joss needs to see we are all working together in this.’

‘Of course. As I said, Joss is an intelligent girl, but she’s throwing it all away.’ Miss Pryce glanced at her watch. ‘I’ll show you some of Joss’s work and then I’m afraid I’ll have to go. I’ve got to see a pupil at one o’clock. But do phone me if you have any concerns.’

‘Thank you. One last thing: does Joss ever talk about her father or stepfather in school, do you know?’

‘Not as far as I know.’

‘Thank you.’

Miss Pryce showed me Joss’s English, Maths and Science folders, which as she’d said held poor-quality or incomplete work, together with a list of work that was entirely missing. I thanked her for her time, said again that I would do all I could to help Joss and then she saw me to reception where we said goodbye. I signed out of the visitors’ book and returned to my car with a heavy heart. While I wasn’t wholly surprised by what Miss Pryce had told me in respect of Joss’s school work, I was surprised and hurt by the level of Joss’s lying about Chloe/Chelsea. I thought back to the time I’d met Chelsea, whom I’d been led to believe was Chloe, when I’d given her a lift home from the cinema. I remembered the girls laughing and sniggering in the back of the car, which I’d put down to self-conscious teenage giggling, but now I guessed they’d been laughing at the deception they’d played on me. I could see the logic in choosing Chloe – an exemplary, hard-working, well-behaved student – for if I did make enquiries at school I’d be told what a good girl she was, which would reflect well on Joss, as opposed to Chelsea, who appeared to attract as much, if not more, trouble than Joss.

But as a parent or foster carer, you can’t afford to stay hurt for long, and by the time I arrived home I was trying to work out the best way to approach Joss without damaging our already frail and rocky relationship. It would have been very easy to make Joss squirm and look small by not telling her I knew of her deception and asking her about Chloe, and then hearing more of her lies before I told her I knew the truth. However, that wouldn’t have given me any satisfaction and certainly wouldn’t have helped my relationship with Joss, so I decided that honesty was the best policy and that I needed to tackle the matter head-on.

‘I’m hot,’ Joss moaned as I opened the door to her that afternoon when she returned home from school. ‘And Miss wouldn’t let me leave the class for a drink of water. It’s against my human rights.’

It was a constant gripe of Joss’s that ‘Miss’ (read: most teachers) had contravened her human rights by not allowing her to leave the class during a lesson – to get a drink, go to the toilet, find a missing book, and so on. But had Joss been allowed to leave, she would have spent more time out of lessons than in them.

‘It’s summer,’ I said. ‘That’s why you feel hot. Fetch yourself a glass of water and then come into the living room, please. I need to talk to you.’

‘Tell me now,’ she said, dumping her school bag in the hall. ‘I’m tired. I need to lie down before I get ready to go out later.’

‘You won’t be going out until we’ve had a chat,’ I said firmly. ‘Do as I ask, please.’

Joss looked at me, slightly taken aback. ‘I don’t want a drink. I’ll come with you now and get it over with.’

‘All right.’ I led the way down the hall and into the living room. The patio doors were slightly open and the fragrant summer air wafted in. Adrian wasn’t home yet, and Lucy and Paula were both in their rooms chilling out.

‘What is it?’ Joss demanded as we sat down – me on the sofa and Joss choosing the chair furthest away from me.

‘I saw Miss Pryce today,’ I said.

‘Yeah, I know. What’s the old bat been saying about me?’

‘She was very pleasant and said you were a clever girl but you’d slipped behind with your work. She said you were capable and had been doing well, but now you had a lot of catching up to do. She wants to help you achieve, as I do, but Joss, why did you lie to me about Chloe?’

‘I didn’t!’ she snapped defiantly, as a reflex action.

‘You did, love,’ I said evenly. ‘Surely you must have known you’d be found out at some point.’ I held her gaze.

‘OK. I did then. Sorry.’ But there was no sincerity in her apology.