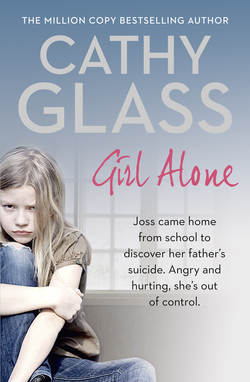

Читать книгу Girl Alone: Joss came home from school to discover her father’s suicide. Angry and hurting, she’s out of control. - Cathy Glass, Cathy Glass - Страница 9

Chapter Four No Daddy Doll

ОглавлениеBecause Amelia was inexperienced she was trying to be Joss’s friend, and it didn’t work. Parents, carers, teachers, social workers and others responsible for a child can’t ingratiate themselves with the young person and still hope to have the authority necessary to put boundaries in place for their safety and acceptable behaviour. Once the child is a responsible adult it’s different – parents often become their friend – but while they are growing up, especially if they are angry and rebellious, as Joss was, then the adults responsible have to take control and accept that sometimes the child won’t like them. I’d seen some very good contracts of behaviour that had worked well, but I thought Joss’s was simply a licence to do whatever she wanted. It wasn’t long before I was proven right.

On the way home in the car Joss lost no time in telling me that, as it was Monday, she was allowed out until 9.30 p.m.

‘After you’ve done your homework,’ I said.

‘I haven’t got any,’ she replied.

I doubted this and I’d asked for a meeting with her teacher to discuss Joss’s education, but for now I had to accept what Joss told me, so she could go out. Once home, she quickly changed out of her school uniform into leggings and a T-shirt, gobbled down her dinner and then left, shouting goodbye as she went. Although Adrian, Lucy and Paula didn’t comment, I knew they felt as I did that it wasn’t good for Joss to be out so much, and they would have liked her to stay in more. Their friends’ parents had similar rules to me, so they generally accepted the boundaries I put in place.

They were upstairs getting ready for bed when Joss returned at ten o’clock. When I let her in I could smell alcohol on her, although she didn’t appear drunk. I was worried more than annoyed.

‘Joss, why do you keep drinking when you know how bad it is for your health?’ I asked wearily.

‘To forget,’ she said, kicking off her shoes.

This was far more revealing than any of her previous responses of ‘dunno’ or ‘none of your business’ or ‘I like it’, so I felt she might want to talk.

‘Joss, I understand you don’t want to see a counsellor, but can you try to share with me what exactly you are trying to forget?’

‘You know already,’ she said. ‘My dad and him.’

‘Do you want to talk about your dad?’ I asked.

‘No.’

‘Do you want to talk about your stepfather?’ I tried.

‘No.’

She began upstairs.

‘Joss, do you talk to anyone – Chloe maybe? – about the things that worry you? We all need someone to talk to.’

She shrugged and continued upstairs. ‘Are you going to stop my pocket money because I was late?’

‘Not if you are back on time tomorrow.’

She paused on the stairs and turned to look at me. ‘Why do you foster? It can’t be much fun.’

I smiled as I met her gaze. ‘Because I like fostering. I like to try to help young people, and if I can make even a small difference I feel very pleased.’

‘But what if you can’t help them?’ she said.

‘It hasn’t happened yet. I always find a way to help a little.’

‘Not with me, you won’t,’ she said bitterly and, turning, continued upstairs.

‘Even with you, Joss,’ I called after her.

‘No. I’m beyond your help.’

Joss cried out in the night, and as usual I went round and resettled her. She wasn’t awake, but I stayed with her until she was in a deep sleep again. It was indicative of the high level of her inner turmoil that she had so many nightmares, but until she opened up and started talking about her profound unhappiness the nightmares would continue – and so too, I thought, would her angry and self-destructive behaviour.

She had breakfast with us as usual on Tuesday morning and I saw her off to school at the door. Then at 9.30 a.m. her school’s secretary telephoned to say that Joss hadn’t arrived. It was school policy to notify the parents or carers if a young person hadn’t arrived by 9.30, and it had happened before. I assumed that, as before, Joss would arrive late, and sure enough at 9.50 the secretary telephoned again to say that Joss had just arrived – an hour late – and that she would be kept in a sixty-minute detention after school to make up the work she’d missed. This was also school policy. I thanked the secretary for letting me know and asked if she’d remind her form teacher that I would like a meeting with her to discuss Joss as soon as possible. She said she’d pass on my message.

School finished at 3.30 p.m., so, allowing for the sixty-minute detention and half an hour on the bus, I was expecting Joss home at about five o’clock. In fact, she arrived home at 5.30, which wasn’t too bad, so I let that go, but I did ask her why she’d been an hour late for school that morning when she’d left the house on time.

‘I went home first,’ she said.

‘What for?’

‘To get a book I needed for school. I thought I might have left it there. They give you a detention if you keep forgetting your books.’

‘And did you find the book?’

‘No. I think I’ve lost it. I tried to tell my teacher the reason I was late, but she didn’t believe me.’

I was suspicious too, but I didn’t say so.

‘Joss, in future it’s better to forget a book than arrive an hour late for school. I was worried where you might have got to.’

‘OK. I did my homework in detention, so can I go straight out? It’s Tuesday and I’m allowed out.’

‘I know, but you’re having your dinner first, and really, Joss, I’d like it if you stayed in. We could watch some television together, or you could spend some time with Lucy and Paula. They’d like that.’

‘I’ll see them tomorrow evening instead,’ Joss said, ready as always with a reply. ‘It’s Wednesday so I’m not allowed out. And you’re taking me to get my sound system from home.’

‘I hadn’t forgotten. If you go out tonight, where will you be going?’

‘To Chloe’s.’

‘I can take you in the car.’

‘No, thanks.’

‘I’ll collect you, then.’

‘No, thanks.’

I couldn’t insist on this as a condition of her going, as I had done with her trip to the cinema, because the contract of behaviour had overridden me.

‘Make sure you’re back by half past nine, then,’ I reminded her. ‘No later.’

She nodded.

Joss arrived back at ten minutes past ten – forty minutes late – and smelling of alcohol, so I told her I was stopping half her pocket money and that she could earn it back through good behaviour: by coming home on time and not drinking for the rest of the week.

‘That’s not fair!’ she yelled angrily.

‘It is fair, Joss. I warned you last night when you were late back that I would stop your pocket money if the same happened again tonight.’

‘I hate you!’ she yelled, and stomped upstairs. ‘I fucking hate you!’

Lucy suddenly appeared from her bedroom in her pyjamas. I could see she was angry.

‘Don’t you dare yell at my mother like that!’ she shouted at Joss as she arrived on the landing. ‘Who the hell do you think you are? You want to be bloody grateful my mum took you in. No one else would!’

‘Lucy!’ I cried, running up the stairs. ‘Calm down.’ I’d never seen her so angry before.

‘You can shut your face too!’ Joss shouted at Lucy.

Lucy raised her hand as if she was about to slap Joss as I arrived on the landing and moved her away. ‘No, Lucy,’ I said firmly. ‘Don’t.’

She lowered her hand and Joss grinned provocatively.

‘Go to your room, now!’ I said to Joss.

She hesitated.

‘I said now!’

Smirking, she went round the landing to her room, slamming the door behind her with such force that the whole house shook.

Lucy was still fuming and looked as though she might go after Joss. I took her arm. ‘Come on, let’s go and sit in your room and talk.’

She came with me into her bedroom and we sat side by side on the bed. We could hear Joss stomping around in her room, nosily opening and closing drawers.

‘Who does she think she is?’ Lucy said. ‘I’m not having her talk to you like that.’

I slipped my arm around her waist and held her close.

‘It’s all right, love.’

‘I’m going to really hit her hard one day,’ Lucy said, clenching her fists in her lap. ‘I just know it. I won’t be able to stop myself.’

I took her hand in mine. While I was touched by Lucy’s loyalty, we both knew that physical violence was never right in any circumstances and if she ever did hit Joss, it would put an end to our fostering forever.

I held her close and gently stroked her hand as she slowly calmed down.

‘I know I shouldn’t have threatened her,’ she said at last. ‘But she gets to me.’

‘That’s what she’s aiming for,’ I said. ‘Joss thinks that if she pushes us too far then I’ll ask for her to be moved, as the other carers did. And that will confirm to her that she really is as bad and unlovable as she believes.’

‘But why?’ Lucy asked, raising her head from my shoulder. ‘She doesn’t have to behave like this. My life was hell for a long time before I came into care. I just wanted to die, so I know how she feels. But she’s safe here, and at some point you have to let go of your anger and move on. You can’t feel sorry for yourself forever.’ Lucy had been through a lot before she came to me two years previously – I tell her story in Will You Love Me?

‘That’s true, but Joss hasn’t reached that stage yet; far from it. She’s harbouring a whole lot of unresolved feelings around her father’s death and her mother remarrying. She feels very rejected.’

Lucy sighed. ‘I know, but how long is this going to go on for?’

A knock sounded on Lucy’s door, and we both looked over as it slowly opened and Adrian poked his head round. ‘Are you two all right?’ he asked, concerned.

‘Yes, thanks, love. We’re OK.’ It was all quiet in Joss’s room now.

‘Paula wants to talk to you when you’re free,’ Adrian said.

‘Please tell her I’ll be with her in a few minutes.’

‘Will do,’ Adrian said, and went out.

‘Joss’s behaviour upsets Paula a lot,’ Lucy said.

I felt even more worried. ‘I’ll talk to her in a moment, but other than keep going as we have been, I’m not sure what else we can do for Joss right now. You’re the same age as her. Have you got any suggestions of how I can help her more?’

‘Not really. I know I was angry about everything that had happened to me, but it came out in different ways. I stopped eating, for one.’

I nodded thoughtfully. Lucy had been anorexic when she’d come to me, but she had recovered now.

‘Could I have done anything differently with you?’ I asked.

‘I don’t think so. You gave me the space and time I needed. I felt safe here, and you were always ready to listen to me when I wanted to talk. You still are.’ She kissed my cheek and I hugged her. ‘Mum, I’ll try to be more patient with Joss, but it’s difficult. Paula and I have welcomed her like a sister, so it makes us really cross when she is horrible to you.’

‘I understand.’

Fostering changes the social dynamics within the family, and the foster child’s age, experience before coming into care, disposition and coping mechanisms all have an effect and create an individual whom the fostering family have to adjust to and accommodate – quickly. Although Lucy was the same age as Joss and knew what it was like to be a foster child, they were very different personalities and at different stages in their lives. I thought it would be best if, for the time being, Lucy put some distance between her and Joss to avoid another flare-up. Lucy certainly wasn’t a violent child, but she was protective of me, and I could see how Joss would wind her up.

‘Lucy, I don’t want you to worry about me, love,’ I said. ‘I appreciate all you’ve done to welcome Joss and help her settle in, but you have your own life to lead, and you’re doing very well. Leave her to me until she’s calmer. I’ll call you if I need your help.’

Lucy threw me a small smile. ‘I think that’s a good idea, or I might do something I later regret.’

‘Good girl. Now you’d better get into bed. It’s late and you’ve got school tomorrow.’

Lucy nodded. ‘I was in bed when I heard Joss kick off.’

I waited until she was back under the covers and then hugged and kissed her goodnight. Reassuring her again that she mustn’t worry about me, I came out and closed her door. I went to Paula’s room next. She was sitting up in bed, using the headboard as a backrest, with her lamp on, and gazing pensively across the room. I went over and she made room for me on the bed, resting her head on my shoulder. We often sat like this for our bedtime chats, but it was getting late – nearly eleven o’clock.

‘You won’t be able to get up in the morning,’ I said gently.

‘I’m not really tired now,’ she said.

‘Try not to let Joss’s behaviour upset you. She’s angry. I don’t take her words personally.’

‘But what I don’t understand is how she can be nice one minute, wanting to play with my doll’s house, and then stomp around and be revolting the next.’ Paula had a really nice doll’s house that she was given as a special present when she was four. Since then she’d bought beautiful furniture for it, so it was really a collector’s piece now. Although she no longer played with it as such, given that she was twelve, it still stood majestically on a small table in the corner of her bedroom where she could see and admire it. I knew Joss liked to play with it, role-playing the family as a much younger child would. She always asked Paula first if she could play with it and Paula always let her.

‘Joss is very confused,’ I said. ‘I’m afraid you’re going to have to try to ignore her mood swings. Don’t take it to heart. She’s had a rough time.’

‘I know. Her dad died and she hates her stepfather,’ Paula said.

‘Does Joss ever talk to you about it?’

‘Not really. But I’ve noticed she never plays with the daddy doll in the house. She hides him in the garage and then plays with the mummy doll and the two children. I almost understand why she hides the daddy, and yet I don’t. My dad doesn’t live with us, but when I used to play with my doll’s house I always included him. I mean, it’s OK to pretend, isn’t it?’

‘Of course it is, love, but then you still see your dad, even though he doesn’t live with us. Joss can’t ever see her dad again, can she? Perhaps that’s why she hides the daddy doll. Perhaps it’s too painful for her to even pretend.’

Paula nodded. ‘That makes sense. I think I might be a child psychologist when I leave school and help children who’ve suffered. It’s interesting the way the mind works.’

‘It is,’ I agreed. ‘And a child psychologist is a very good career,’ I added, although I knew, of course, that Paula was young and could easily change her mind before she decided on a career.

‘Will Joss see a psychologist?’ Paula now asked.

‘Hopefully, or a counsellor, when she feels ready.’

‘I think it could help her, don’t you?’

‘I do,’ I said.

‘I don’t like it when she’s so angry.’

‘I know, love, it’s frightening to watch, but you know I’ll always protect you.’

She hugged me hard.

‘Was there anything else you wanted to talk about?’

‘Not really. I just wanted to make sure you were all right, and tell you I love you.’

‘I love you too,’ I said. ‘I’m fine, so don’t you worry about me. And, Paula, it’s nice that you let Joss into your room whenever she wants, but you know you don’t have to. If you want time alone, you can just tell her politely that you’ll see her later.’ I wondered if perhaps Paula was intimidated by Joss’s angry outbursts and felt she had to do whatever she asked.

‘I usually let her in because I feel sorry for her, and she’s OK to be with sometimes.’

‘That’s fine. But remember you don’t have to. It’s your room.’

We hugged and then I kissed her goodnight and came out. Thankfully, Paula and Lucy could talk about their worries. It was all quiet in Joss’s room, but I wanted to make sure she was OK too, so I went round and, giving a small knock, quietly opened her bedroom door. She always slept with the light on low, so I could easily see from the door that she was in bed and fast asleep. I closed the door again. There was no sound coming from Adrian’s room either, so I lightly knocked on his door and then slowly opened it. His room was in darkness, so I knew he was in bed asleep.

‘Night, love,’ I whispered.

‘Night, Mum,’ came his muffled, sleepy reply.

I closed his door and went downstairs. Thankfully, Adrian had taken the last of his GCSE examinations that day, so I no longer had the added worry that Joss’s rages might be disturbing his studies. Downstairs I settled Toscha in her bed for the night and then locked up. By the time I climbed into bed it was nearly midnight and I was exhausted. Despite my concerns about Joss and the impact her behaviour was having on the rest of the family, I soon fell asleep. Joss must have been exhausted too, for she slept through without a nightmare and I had to wake her in the morning.

‘A new day, a fresh start’ is my motto, but there was an atmosphere at breakfast between the girls. No one was usually very talkative at breakfast anyway, but this morning there was a frosty silence, broken only by the sound of cutlery on china. When Joss stood to take her empty cereal bowl into the kitchen she caught the table and it jolted against Lucy, who was sitting opposite. Possibly it was an accident, although Lucy clearly didn’t think so.

‘It’s not clever,’ she hissed at Joss.

‘Touchy!’ Joss retaliated with a sneer.

I motioned for Lucy not to say anything further, and Joss put her bowl in the sink and then went upstairs to get ready.

‘Sorry,’ Lucy said after she’d left the room.

I nodded and let it go. Joss had provoked Lucy – intentionally or by accident – and Lucy had retaliated instead of ignoring it. She’d apologized, so that was the end of the matter.

When Joss was ready I saw her off at the door, reminding her to come straight home, as we had to be at her parents’ house at five o’clock.

‘Mum’s house,’ she corrected. ‘It’s not his.’

‘OK. See you later,’ I said.

Adrian, Lucy and Paula left soon after. Although Adrian had taken his exams, he was still expected to attend school until the end of the summer term, in six weeks’ time. Jill telephoned mid-morning and, having asked how we all were, she said she’d raised concerns about the behaviour contract with Amelia. She’d pointed out that it was too lax to be of any use, but Amelia had said she felt that if the rules were any stricter Joss would rebel against it and not cooperate at all.

‘She’s barely cooperating now,’ I said. ‘I hope Amelia appreciates that while Joss is out of the house I cannot be held responsible for her safety or what trouble she might get into.’

‘I made that clear,’ Jill said. ‘Sadly, Amelia thinks a secure unit might be the only option for Joss in the end. You can only do your best.’