Читать книгу The Bell Tolls for No One - Charles Bukowski - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

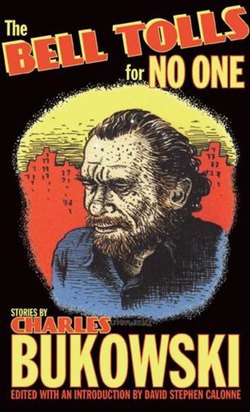

Charles Bukowski’s Graphic and Pulp Fiction

David Stephen Calonne

Charles Bukowski was devoted to “graphic fiction” from the beginning of his career: one of his earliest works, “The Reason Behind Reason,” published in 1946 in Matrix, is adorned with a lively drawing depicting the anti-hero Chelaski with legs flying, arms outstretched comically attempting to catch a flying baseball.1 During his years crisscrossing America between 1942 and 1947—a period in which he sometimes had to pawn his typewriter due to lack of funds—Bukowski also submitted to Whit Burnett, editor of the celebrated Story magazine, a series of hand-printed, illustrated short stories, including “A Kind, Understanding Face,” demonstrating that he often conceptualized text and image together in a complementary relationship. He wrote Burnett from Los Angeles in November 1948: “I thought the drawings came out especially well in this one and I hope you do not lose it.”2 Burnett urged Bukowski to collect his drawings in book form and also repeatedly asked him to consider writing a novel. On October 9, 1946, from Philadelphia, Bukowski also composed an illustrated letter to Caresse Crosby, publisher of Portfolio. Already he had developed the clean line style of his charming, minimalist, Thurberesque drawings which could not but ingratiate him to prospective famous editors such as Crosby and Burnett. Here a stunned man with a bottle and lines for eyes drinks, smokes, and lies in bed with bare lightbulb, curtain with a drawstring, bottles on the floor. Later he would add sun, flying birds, companionable dogs. Psychologically, it is clear that these gently humorous drawings were one of the ways he had developed to deal with his considerable childhood wounds: his physical abuse by his father, the eruption of acne vulgaris, his status as misfit German-American. Here was a medium in which he could play and entertain, qualities he also strove for in his writing.

The autobiographical “A Kind, Understanding Face” (1948) begins with an epigraph describing a crippled spider being dismembered alive by ants and sets the theme for many later stories: Nature red in tooth and claw. The protagonist, Ralph, like the young Bukowski, avoids the draft, has journalistic ambitions, and wanders the country from Miami to New York to Atlanta. Though Ralph is in some respects a stand-in for the author, in the story his father and then his mother are deceased, while Bukowski’s mother Katherine died in 1956 and his father Henry in 1958. The tale presents a series of odd, disjunctive events, concluding with three mysterious quotations, appended without citations: one from Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel, Book Five, Chapter 30, “Our Visit to Satinland”; another from George Santayana’s “Ultimate Religion” (1933); and finally a reference to René Warcollier (1881–1962), the French chemical engineer who developed a method of making precious stones synthetically and who also published Experiments in Telepathy (1938).3 Given that there is a reference to copulating and defecating in public, it’s possible that Bukowski by this time had also encountered the writings of Diogenes the Cynic (ca. 412 CE–323 CE). Just as the narrative itself is weirdly dissociative, these three allusions left in the suicide note of young Ralph seem a kind of fragmentary riddle or hidden message which the reader is meant to assemble and decode: What, if any, is the connection between Diogenes, that odd manticore, the lofty language of Santayana, and the making of jewels from fish scales? One recalls Vladimir Nabokov: “Human life is but a series of footnotes to a vast obscure unfinished masterpiece.” The range of these rather recherché allusions indicates the depth of Bukowski’s reading, and placing them one after another may suggest the absurdity of the quest for meaning as well as the indecipherability of an obscure unfinished life.

From the beginning of his career, Bukowski depicted the terrible human encounter with the Other: insects (here spiders and ants) in particular pullulate through many of his early poems and stories. His work also shows the influence of Robinson Jeffers’s hawks and herons as well as D.H. Lawrence, whose Birds, Beasts and Flowers can be heard echoing in the title of Bukowski’s first book of poems, Flower, Fist and Bestial Wail. Mockingbirds, wild horses, and dogs appear in three other poetry titles. In the stories in this volume, there is a frightening encounter with a hog, while another tale set in Bolivia depicts a man, a woman, and a monkey engaging in a bizarre psychological battle, a theme Bukowski would return in his late story “The Invader” (1986).4 And in “The Bell Tolls for No One,” the narrative draws to a close on an awesome note: “Then in front of me there was an animal. It looked like a large dog, a wild dog. The moon was to my back and it shone into the beast’s eyes. The eyes were red like burning coal.”

In the same issue of Matrix as “The Reason Behind Reason,” Bukowski’s poem “Soft and Fat Like Summer Roses” appeared, recounting a love triangle involving a waitress, her husband, and her Greek lover; this suggests Bukowski most likely had read James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934), in which the plot is very similar, though the restaurant owner is Greek and the other man steals his wife. Cain famously shaped the style of Albert Camus’s L’Etranger—the French existentialists owed a debt to the cool, tough American private eyes—and Bukowski also acknowledged Cain’s style as a significant influence on his own work.5 Like Cain, Bukowski often takes a detached, clinical view of crime, and Los Angeles noir would be the style of his many “hardboiled” crime stories, culminating in his homage to the genre, his final novel, Pulp (1994).6 When Irene in one of our tales tells the Bukowski-character that he is the “greatest thing since Hemingway,” he responds: “I’m closer to Thurber mixed with Mickey Spillane”: the hero of Pulp is tellingly named “Nick Belane,” obviously echoing “Mickey Spillane.” Of course, Bukowski’s gift for dialogue, monosyllabic Anglo-Saxon vocabulary, and skeletal, pared-down prose derives from Hemingway, supplemented with elements he often said he found lacking in Hemingway: humor, as well as liberal doses of slang, swearing, scatology, and obscenity. The title “The Bell Tolls for No One” is an obvious reference to Hemingway’s novel For Whom the Bell Tolls, while in another story a pornographer husband and his wife carry on a humorous dialogue about Hemingway.

Bukowski often returned nostalgically to the legendary outlaws of the 1930s, and in the poem “the lady in red” recalled: “the best time of all / was when John Dillinger escaped from jail, and one of the / saddest times of all was when the Lady in Red fingered him and / he was gunned down coming out of that movie. / Pretty Boy Floyd, Baby Face Nelson, Machine Gun Kelly, Ma / Barker, Alvin Karpis, we loved them all.”7 For Bukowski, as for a writer in every way his opposite, William S. Burroughs (one of whose favorite books was Jack Black’s 1926 autobiography chronicling his adventures in the underworld, You Can’t Win), the American power structure was criminal at its very core and found its mirror image in the violent figures who struggled against it.8 Cain, Spillane, Dashiell Hammett, and Raymond Chandler depicted a hard, amoral universe that shows no mercy and provided Bukowski a tradition within which to dramatize his mythicized autobiography. His 1947 meeting with Jane Cooney Baker at the Glenwood Bar on Alvarado Street becomes a tale endlessly told and retold, shaped and refined. In a 1967 story for Open City he declares that Jane “had delicious legs and a tight little gash and a face of powdered pain. And she knew me. She taught me more than the philosophy books of the ages”—casting Jane in the film noir role of femme fatale. And the violence of this broken world is continual. Wallace Fowlie once wrote about Henry Miller: “I believe the quality which first attracted me in Mr. Miller’s writings was his violence. Not the violence of the things said, but the violence of the way in which they were said. The violence of feeling has become in his work the violence of style which has welded together all of his disparate passions and dispersed experiences into the one experience of language.”9 Similarly, Bukowski evolved his own original finely modulated “language” to portray a modern world in which the redemptive power of love was under continual threat.

“Nothing is true, everything is permitted” was a phrase of Hassan-i Sabbah (ca. 1050 CE–1124 CE), the Ismaili founder of the Hashshashin, repeated like a mantra by William Burroughs. In The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky proclaims: “If God does not exist, then everything is permitted,” and Karamazov is cited in “A Dirty Trick on God.” Another Bukowski favorite, Friedrich Nietzsche, declared in The Genealogy of Morals:

When the Christian crusaders in the Orient encountered the invincible order of the Assassins, that order of free spirits par excellence, whose lowest ranks followed a rule of obedience the like of which no order of monks ever attained, they obtained in some way or other a hint concerning that symbol and watchword reserved for the highest ranks alone as their secretum; “Nothing is true, everything is permitted.” Very well, that was freedom of spirit; in that way the faith in truth itself was abrogated. Has any European, any Christian free spirit ever strayed into this proposition and into its labyrinthine consequences? Has any of them ever known the Minotaur of this cave from experience?—I doubt it.10

“The labyrinthine consequences” of such a philosophy become the subject matter of Bukowski’s repeated portrayals of his characters’ encounters with the Minotaur of the cave of unrelenting chaos. Crime becomes a metaphor for an unjust universe in which reward and punishment often seem unrelated to virtue: The unyielding, brutal, and powerful “Break In” contains an explicit speech on the unfairness of society, and in Bukowski the narrator often observes the occurrences helplessly, without commentary. He is at once quasi-participant and observer.

Yet these stories also demonstrate Bukowski’s wide range; he can be witty, casual, intimate, and ingratiating, and he tries his hand at a variety of genres: science fiction, a send-up of Westerns, stories of jockeys and football players. While he is devoted to chronicling the Sturm und Drang of his private, emotional life, the political and social upheavals of the mid to late sixties are frequently portrayed, as in “Save the World,” which depicts his relationship with his partner Frances Smith. Although he pokes fun at Frances’s devotion to liberal causes, Bukowski had met—and liked—Dorothy Healey, giving her inscribed copies of Cold Dogs in the Courtyard and Crucifix in a Deathhand. He wrote Will Inman, editor of Kauri: “Dorothy Healey, spokeswoman for the Communist Party, came to visit me. I was honored. I have no politics, but I was, nevertheless, honored.”11 One tale imagines an apocalyptic 1968 presidential victory of George Wallace and his vice-presidential choice, the Air Force general Curtis Le May; others make incisive comments on the return of American POWs following the end of the Vietnam War and allude to Bukowski’s own questioning by the F.B.I. during the period he was under investigation for his supposedly incendiary writings for the underground press.

The political ferment of the period—from approximately 1967 to 1973—corresponds exactly with one of Bukowski’s most brilliant and prolific phases. One might argue that the eruption of Dionysian sexual energy was directly related to the anti-war stance of the time: Make love not war. The gradual loosening of censorship restrictions allowed writers and artists new freedom for self-expression. Centered in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, the “comix underground” had taken off with the appearance of the famous Zap #1 in 1968.12 Bukowski himself continued to draw and paint prolifically and would ultimately get to know personally or have professional association with the three major figures of underground comics: Robert Crumb, Spain Rodriguez, and S. Clay Wilson.13 An admirer of Bukowski’s writing, Robert Crumb demonstrated his genius at capturing its German Expressionist tragicomic essence in his illustrations for Bring Me Your Love, There’s No Business, and The Captain is Out to Lunch and the Sailors Have Taken Over the Ship.14 Bukowski himself now began to draw cartoons for his stories in Open City and the Los Angeles Free Press. He also created several stand-alone comic strips such as “Dear Mr. Bukowski”—a hilarious account of a more-than-usually crazy day in his life—which appeared in the June 27, 1975, issue of the Free Press and was then printed as a silkscreen set of fifty signed copies in 1979, as well as a series titled “The Adventures of Clarence Hiram Sweetmeat,” which appeared in the October 24, 1974, and September 19, 1975, issues. The installment that appeared in the October 3, 1975, Free Press was published in 1986 in book form as The Day It Snowed in L.A.

Just as Burnett had in the forties, John Martin—who had begun publishing broadsides of Bukowski’s poetry in 1966—urged Bukowski to write a novel. He worked on a manuscript titled The Way the Dead Love that was never completed, but several chapters were published in magazines.15 One chapter, which appeared in Congress (1967), vividly described some sexual hijinks involving “Hank” (Bukowski), “Lou,” and a young lady in a cellar, and demonstrates Bukowski’s newfound, jaunty, erotic style. In the early 1970s, it now seemed natural for him to begin writing for the men’s magazines in order to supplement his income. Four stories in this volume—“The Looney Ward,” “Dancing Nina,” “No Quickies, Remember,” and “A Piece of Cheese”—were submitted to Fling, published by Arv Miller in Chicago. Bukowski created the title “Hairy Fist Tales” as the rubric for the series, and the phrase likely derived from a poem he had published in the Grande Ronde Review 6 in 1966, “the hairy, hairy fist, and love will die,” a fierce and frightening description of total spiritual defeat: “your soul / filled with / mud and bats and curses, and the hammers will / go in / there will be hairy / hairy / fists and / love will / die.”16 These tales, however, are light-hearted and rambunctious. Bukowski had read Boccaccio, and the fabliau technique of folk-story telling familiar from Chaucer can be seen as well in “No Quickies, Remember” in which, as in a joke, the same story is repeated several times, leading to a surprise ending.

Bukowski began writing a series of stories about the women he met during the period 1970–1976 which would ultimately take shape as the novel Women, and the Los Angeles Free Press began serializing them in the February 13–19, 1976, issue with an editor’s note calling the sequence a “novel-in-progress” under the title Love Tale of a Hyena. (The title was kept for the German edition of the novel: Das Liebesleben der Hyaene.)17 His relationship with Linda King is portrayed. Liza Williams appears in several; at one of her parties, Bukowski describes meeting Robert Crumb (but declines the invitation to meet the editor of The Realist, Paul Krassner). Writing and women form a constant counterpoint in his stories. He plunges into the cauldron of love, passion, sex, attempting to heal the wounds of his past, attempting to find in romantic love a salve for the demons that try him. Yet he can only momentarily find such redemption, and returns to his self, and gains distance from his solitude by crafting the experiences into narrative. His life exists mainly to be transcribed and transformed into words. He goes to Arizona, describing himself writing, and immediately refers to Gertrude Stein and Hemingway, weaving in his encounters with women and children and the life immediately taking place around him at the moment. Sex is a matter of occasional ecstasy and frequent laughter; love is a matter of life and death: He gives us both, in alternation. The stories also exemplify the gender wars of the period, during which women’s liberation had begun. Bukowski typically reverses the situation to show how the “politically correct” stance can be easily turned on its head. He also, however, satirizes men, and shows the absurdity of the whole romantic love complex. Pathos, farce, tragedy: Often, humor saves the situation. He is able to defuse the pain by poking gentle fun at the entire absurdity of love relationships. Massage parlors, a pornographer engaging in late-night discussions with his wife, adult bookshops, older women picking up younger men: The entire panoply of the fading sexual revolution is held up to satire and ridicule.

Bukowski’s shift to becoming a “professional writer” in 1970 in some ways altered his method of composition. He had always reshaped the same material into poem and story, but now he was devoting his time to writing novels as well as submitting to the adult magazines. Several of the stories included in this volume demonstrate how he worked and reworked this material. He creates the same narrative anew; he doesn’t copy, but starts over. He is always telling his autobiography but selecting different details, reinventing instead of rewriting. For example, “An Affair of Very Little Importance” about Mercedes exists in another version in Women, but the narrative and emphasis are different. And the story “I Just Write Poetry So I Can Go to Bed with Girls,” for example, also exists as the “Dirty Old Man” installment included here: It keeps some of the plot, but takes a completely different approach to the meeting with Gregory Corso.18 It is typical of Bukowski’s method of selecting episodes from his life and reworking them, adding specific details and usually elaborating on reality by adding invented plot elements. He is constantly engaged in telling and retelling his life, giving it the structure of myth so that the two become inseparable. The basic structure of his life is mythic, a variation on the hero’s journey, the genius as hero: his abandoned childhood, primal wounding by his father, and his skin disfiguration, his wanderings in the wilderness, his near-death by alcoholism in 1954, and his resurrection.19

These stories from 1948–1985 demonstrate Bukowski’s growth as a writer of short fiction. He gradually hones his craft and learns how to combine the tragic and comic modes effortlessly. In his late phase, Bukowski had mastered his style to the point of making the laconic, finely modulated prose we see in “The Bell Tolls for No One.” The mood is swiftly established, and not a word is wasted. His goal in his fiction was to entertain, yet he was driven to explore the dark places, the Nietzschean cave with the monstrous Minotaur. As he once said: “I can’t name it. It’s just there. The thing is there. I have to go see it. The monster, the god, the rat, the snail. Whatever’s out there I have to go see it and look at it and endure it and maybe not endure it but it’s needed. That’s all. I really can’t explain it.”20 The unspeakable, monstrous, inscrutably violent and tender mystery at the heart of existence will not leave him in peace.