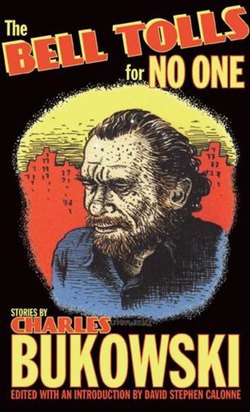

Читать книгу The Bell Tolls for No One - Charles Bukowski - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSave the World

She came in and I noticed that she was banging into the walls and her eyes didn’t seem to focus. It was the day after her writer’s workshop, and she always seemed that way as if she had been taking dope. Maybe she was. She hit the kid for spilling her coffee and then got on the telephone and had one of her everlasting “intelligent” conversations with somebody. I played with the little girl who was my daughter. She hung up. “Are you all right today?” I asked.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, you act kind of . . . distracted.”

Her eyes looked like the eyes of people in movies who played at being insane.

“I’m all right. Are you all right?”

“Never. I’m always confused.”

“Have you eaten today?”

“No. Mind throwing some potatoes in the pot to boil? The pot’s in the sink, soaking.”

I had just come out of the hospital and was still weak.

She walked into the kitchen, then stopped and looked at the pot. She propped, stiff, swaying in the doorway as if the pot were an apparition. It couldn’t have been the kitchen that scared her because she had been the worst housekeeper of all my ex-wives.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

She didn’t answer.

“The pot’s all right. It just has soapwater in it. Just scrub it out a bit and dump it.”

She finally came out, walked around a bit, bumped into a chair, then handed me a couple of magazines: PROGRAM OF THE COMMUNIST PARTY U.S.A. and AMERICAN DIALOGUE. DIALOGUE had a cover of a baby asleep in a hammock made out of a couple of gun belts with bullets protruding. The cover also indicated the contents: THE MORALITY OF OUR TIMES. ON THE SUPERIORITY OF THE NEGRO.

“Look, kid,” I said, “I’m not much on politics of any kind. I’m not much good that way, you know. But I’ll try to read this stuff.”

I sat there and went through it, a bit of it, while she put some meat on in the kitchen. She called me in and the kid and I went in. We sat down to it.

“I read about the superiority of the Negro,” I said. “You know, I am an expert on the Negro. Down at work most of them are Negroes . . . ”

“Well, why don’t you just be an expert on Whites?”

“I am. The article spoke of the ‘fine, tough muscular system. The beautiful, rich color, the full broad features, and the gracefully frizzled hair of the Negro’ and that when Nature got to the white man she was pretty well exhausted, but she pinched up his features and did what she could.”

“I knew a little colored boy once. He had the softest, shortest hair, his hair was beautiful, beautiful.”

“I’ll try to read the Communist Party Program tonight,” I told her.

“Have you registered to vote?” she asked.

“I never have.”

“You can register at your nearest school on the 29th. Dorothy Healey is running for County Tax Assessor.”

“Marina is getting more beautiful every day.” I spoke of my daughter.

“Yes, she is. Listen, we’ve got to go. She goes to sleep at 7. And there’s something I must hear on KPFK. They read one of my letters over the air the other night.”

KPFK was an FM radio station.

“All right,” I said.

I watched them leave. She pushed the kid across the street in the stroller. She had the same old wooden stride, nothing fluid at all. I watched them go. A better world. Jesus. Everybody has a different way, everybody has a different idea, and they are all so sure. She’s sure too, that wooden woman with the insane eyes and grey hair, that woman running into her walls, crazy with life and fear, and she would never quite believe it that I didn’t hate her and all her friends who gathered 2 or 3 times a week and praised each other’s poetry and were lonely and who made each other, and carried signs and were very enthusiastic and sure, they would never believe that the solitude, the privacy I asked for, was only to save myself so I might guess who they were and who the enemy was supposed to be.

Still it was nice to be alone.

I walked in and slowly began washing the dishes.