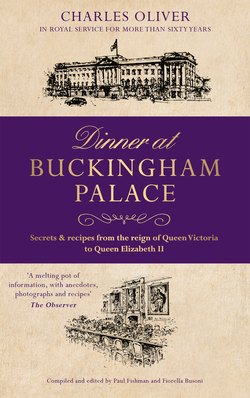

Читать книгу Dinner at Buckingham Palace - Secrets & recipes from the reign of Queen Victoria to Queen Elizabeth II - Charles Oliver - Страница 26

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Side Table

ОглавлениеBaron of Beef

Wild Boar’s Head

Game Pie

Brawn

Woodcock Pie

Terrines de Foie Gras

Osborne House was a favourite retreat of Queen Victoria, filled for her with happy memories of the days before the death of Prince Albert in 1861. Family members plus a few invited guests would join her there for Christmas. Other than plum pudding, there is little to indicate that this was a specifically Christmas meal. Although still hugely excessive, Queen Victoria’s dinners were slightly simpler and less extravagant in the 1890s than in the early days of her reign. Some more traditional dishes were listed under their English names while Monsieur Menager, the Queen’s head cook, retained the French names of the less plain dishes.

Potage à la Cressy (also Crécy) is a traditional carrot and potato soup, and is named after Crécy-en-Ponthieu in northern France, which was said to produce the best carrots in the country. The Cressy soup served in Buckingham Palace was made to a recipe especially developed for Queen Victoria by Francatelli. Victoria’s son, Edward VII, while he was on the throne (1901–10), reportedly had Cressy soup every 26 August to commemorate the English victory under his namesake King Edward III at the Battle of Crécy, on that day in 1346.

* * *

For all his reputation as a playboy (or maybe a little bit because of it), Edward VII was a popular king. By contemporary standards, he was a liberal monarch; he condemned prejudice, patronised the arts, was a good diplomat and had considerable charm. He also liked to eat, and did not restrict himself. A typical lunch for six might include cold pheasant, a couple of partridges, two hot roast fowls, and hot beefsteaks. (This would come not too long after a substantial cooked breakfast.) Dinner always featured a choice of at least two soups, whole salmons and turbots, vast saddles of mutton and sirloins of beef, roast turkeys, several kinds of game such as woodcocks, plovers and snipe, a large array of vegetables, perhaps some devilled herring and cream cheese, an assortment of pastries, and enormous Stilton and Cheshire cheeses. This would be accompanied by an abundance of wines, followed by nuts and preserved fruits, then Madeira, port or sherry.

The Jockey Club Dinners, for instance. Founded around 1750, or earlier, the Jockey Club was an exclusive gentlemen’s club whose members shared an interest in, and knowledge of, horses and horse racing. In time it became a regulatory body, establishing rules to ensure races were run fairly; today, while its functions and responsibilities have changed, it continues to thrive and owns fifteen of Britain’s most famous racecourses. The King, as a connoisseur of horses and racing, was of course a member and hosted the Club’s annual dinner, held on the day of the Epsom Derby, at the Palace. These meals were of eight to ten courses, most courses offering a choice of dishes, and all accompanied by a generous selection of fine wines.