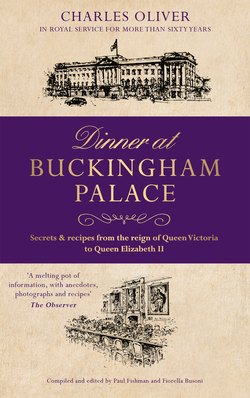

Читать книгу Dinner at Buckingham Palace - Secrets & recipes from the reign of Queen Victoria to Queen Elizabeth II - Charles Oliver - Страница 30

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

POST-WAR RESTRAINT

ОглавлениеAll changed abruptly with the First World War. Eating traditions had been slowly transforming since King George V ascended the throne, as he had the appetite of a professional sailor rather than a social gourmet. With the onset of wartime restrictions, he and Queen Mary insisted on rationing in the palace even before the nation was subjected to it. The Queen would let no member of the family eat more than two courses for breakfast and at her insistence the royal chefs became skilled at contriving mock meat cutlets from mutton purée. Although Mary was undoubtedly one of the greatest connoisseurs of food the palace has known, she set a steadfast example in changing and simplifying the royal eating habits. George V, meanwhile, prohibited the drinking of wine, or indeed any alcohol, as long as the war lasted. The royal chef, shocked, sent a note up to their majesties asking what he should serve instead. Queen Mary wrote back: ‘Sugar water. Serve water, boiled with a little sugar.’ And this is what the Royal Household and its guests drank until rationing was lifted. The King took to drinking a thin soup for elevenses, nearly always had mashed potatoes instead of anything fancy, and seemed never to tire of apple dumplings for dessert. On the few occasions the King and Queen entertained on any scale at the palace during the war, no meat was served at either luncheon or dinner.

* * *

In 1923, Prince Albert (‘Bertie’), second son of George V and Queen Mary, married Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (after she’d turned him down a few times for fear of losing her ‘freedom to think, speak and act’ by marrying into the royal family). For the prince it was a parting from tradition – a ‘modern’ move – in that she was not born a princess (as the daughter of a peer, she was just about acceptable). Famously, as the two entered the Abbey to be married, Elizabeth laid her bouquet on the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior. The ceremony was followed by a fine wedding breakfast prepared by Gabriel Tschumi, with the fish dish named for the prince’s mother, the lamb for the prince, and a strawberry confection for his bride.

There were no fewer than fourteen wedding cakes, the main one (created by Huntley & Palmers) weighed 300 pounds, was about eight feet tall, its four elaborate tiers displaying models of, among other monuments or symbols, Windsor Castle, Glamis Castle, various crests, bells, a tower, and happy cupids making their way up to the top of the cake, where there was a vase containing a bouquet of flowers.

* * *

The final death knell of the old days of gluttony and waste was sounded in 1932 when a big cut was made in court expenditure and the royal household staff was greatly reduced, with many older servants being pensioned off. Gabriel Tschumi was one of those, but Charlie Oliver stayed on.

Tschumi returned to work for the royal circle ten years later as chef to the widowed Queen Mary, who was now living in Marlborough House, a ten-minute walk from Buckingham Palace. ‘Queen Mary, though first and foremost a queen in every sense, was a careful and wise household manager,’ he wrote in his memoir Royal Chef: Recollections of a Life in Royal Households from Queen Victoria to Queen Mary, which was published in 1954. ‘She selected all menus herself. Sometimes there would be eight or ten guests at supper. They were always light, simple suppers, consisting of a salad and dessert, or perhaps savouries and bridge rolls as Queen Mary liked them – prepared with the entire centre scooped out and filled with minced chicken in mayonnaise. Sometimes guests would include the Duchess of Kent, the Princess Royal [Queen Mary’s daughter, Mary, Countess of Harewood], or the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester.’

In 1936, following first his father George V’s death in January and then the abdication of his brother Edward VIII, Prince Albert ascended the throne in December, choosing the regnal name George for continuity. The royal attitude to food and diet was changing decisively, with preferences inclining towards more ordinary food. When Mrs Roosevelt served George VI and Queen Elizabeth hot dogs as typical American fare, the royal couple was amused. (It does not bear thinking what the King’s grandfather, Edward VII, would have said.)

In the days soon after the war, when food was still scarce, the palace continued faithfully to observe rationing and similar restrictions confronting other families. On one occasion George VI and Elizabeth were holding a small private dinner party, and the kitchen had been instructed accordingly. Unfortunately, the head chef was off duty for the night and a deputy had been put in charge of the meal. Still more unfortunately, an old army buddy of the deputy chef had called by earlier that evening to renew his acquaintance and there had been a certain amount of celebrating. Heedless of his alcohol-induced limitations, the deputy chef proceeded to cook the meal – and burnt it beyond hope of revival or disguise. White-faced, he gave the terrible news to a footman, who passed it on to a page, who then had the misfortune to have to relay it to the King. The poor chef fully expected to be escorted to the Tower, particularly as, due to current circumstances, the royal cupboard was literally bare, with absolutely nothing to replace the incinerated meal. The King reacted swiftly and, for all the fears below stairs, with understanding, though neither did he attempt to hide his annoyance as he issued an immediate instruction to send out to the nearest hotel for four dinners. Half an hour later dinner duly arrived, rushed to the palace in heated containers by breathless kitchen staff. Nothing more was said about the incident. The King even forgave the deputy chef, who remained employed in the palace kitchens for many years.

An intentional departure from austerity was when the elder daughter of Elizabeth and George VI, also called Elizabeth, married in 1947. Her wedding breakfast consisted of only four separate courses, but was nevertheless pretty lavish in the circumstances. It was two years after the end of the Second World War, the UK was still under rationing, and it was a chilly, grey November day. None of this put a dampener on the marriage of Princess Elizabeth to Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten, newly created Duke of Edinburgh, formerly Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark: the wedding was an occasion of tremendous joy and hope, as well as splendour and, even, luxury.

The wedding breakfast, which was held in the afternoon, after the ceremony, was for 150 guests, largely formed of the bride’s and groom’s extended families, with a few notable exceptions such as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor and the Duke of Edinburgh’s German relatives, whose presence so soon after the war might have been an embarrassment. In line with tradition, the bride and groom each had a dish named in their honour, the Bombe Glacée Princesse Elizabeth being particularly luxurious, generously garnished as it was with fresh strawberries from the royal hothouses. There were eleven wedding cakes: the main cake, four tiers, and about nine feet tall, weighed about 500 pounds and contained three gallons of Navy Rum, 80 oranges and 660 eggs. It became known as the ‘10,000-mile cake’ as ingredients had to be shipped in from all around the world.

Like her father, Elizabeth has not gone in for ostentatious banquets, preferring simple, good-quality food. As a more recent former royal chef remarked, she is not a foodie. Even her coronation dinner was restrained, with five courses, wine and coffee.