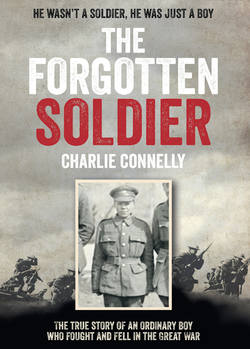

Читать книгу The Forgotten Soldier: He wasn’t a soldier, he was just a boy - Charlie Connelly, Charlie Connelly - Страница 10

4 ‘A half-deaf kid from the slums of Kensal Town’

ОглавлениеIt would be more than a year before Edward was christened, perhaps suggesting he was a sickly baby for whom the first year was touch and go. But he survived and by 1901 the family had moved from Gadsden Mews to Admiral Mews, a few hundred yards west, close to the railway lines. It doesn’t seem as if they were moving up in the world. Booth’s notebooks, having set out the extreme poverty of the surrounding streets, described Admiral Mews as: ‘If anything worse than the foregoing. Houses on north side only and a few stables at the eastern and western extremities. Rough, noisy, all doors open, passages and stairs all bare boards, the usual mess … Gipsy looking women standing about, Irish. The worst of this block of streets.’

Two-year-old Edward was no longer living with his parents. Instead he was living with his grandparents, which was probably more to do with the nature of the tenements than any family disagreements. They were living in the same building, but George and Marion were in one room with Robert, my grandfather, aged eight, while Marion’s parents, the Christophers, George and Mary-Ann, lived with Edward in two rooms along with their 42-year-old son John.

Edward received some rudimentary schooling at the local mission school, but for families like the Connellys the capacity to supplement the meagre household income was always the priority, and Edward would have been sent out to work as early as possible, probably at the age of fourteen. In the 1911 census, when he was twelve, he was still living with his grandparents and his uncle John in Admiral Mews, close to his parents, but there’s one extra detail: on the census return Edward is described as ‘a bit deaf’.

Within weeks of that census John Christopher died suddenly at home from a brain haemorrhage. It’s very possible Edward was there as his uncle held his head, let out an agonised cry and lurched across the room, scattering furniture and belongings before crashing to the floor in the corner, limp, motionless and ash-grey.

Edward next turns up in the 1915 wage books of the Great Western Railway’s Old Oak Common railway depot, a vast establishment that employed a large number of local men and boys. Edward’s job was washing railway carriages, not a pleasant task in the age of steam and unchecked industrial pollution. He’d finish his shifts grimy and black with soot and filth, exhausted and arm-sore from the relentless brushing, but he was bringing in an income, which for a half-deaf kid from the slums of Kensal Town was about all that could be asked of him.

It’s after this that the trail goes cold until Edward’s death. He would have been fifteen years old when war broke out in the summer of 1914, but it’s impossible to know what kind of impact it would have had on him and life in Kensal Town. His uncle Robert would have gone off to fight almost immediately, but we can only guess at how this might have affected Edward. Were they close? Robert lived in the same warren of streets, so he would probably have been a regular visitor to his sister and grandparents. Edward would have seen his uncle frequently as he grew up, but what would his thoughts have been about the war? How would he have taken the news of his uncle’s death in 1916? Would he have expected to go? Would he have tried to enlist under-age? What was the nature of discussion among his friends and neighbours? The talk around Admiral Mews – of enlistment, of the men who had already gone, of the prospects for a quick resolution to the conflict – would have been replicated in every street and among every boy of Edward’s generation. There hadn’t been an event in history at that point to unite a nation and affect its everyday life like the First World War. It permeated every county, every town, every street and every home. Nobody was unaffected.

Most of us will have an Edward Connelly in our backgrounds: a youngster born on the cusp of centuries who’d grow up to be a participant, willing or not, in the greatest war and the greatest tragedy of the modern age up until then. These lads weren’t poets, they weren’t officer material – they did nothing heroic beyond their best. They went off to war as cheerily as they could, made the best of it, had no say in its strategy or planning and just did what they were told. Many of them came home afterwards and resumed their lives; others didn’t and lie to this day in the soil of France, Belgium and further afield. These lads were raised among grimy cobbles rather than the playing fields of Eton, and there were thousands of them right across the land.

Take Admiral Terrace, for example, where the Connellys and the Christophers lived. According to the 1911 census there were twenty-nine households in Admiral Terrace containing 127 people of all ages, from elderly couples to enormous family broods crammed into the pokey rooms of eleven shabby buildings. I combed through these records for the names of men and boys who would have been of official military age during the First World War and then compared those names to any surviving military records I could find. I unearthed eight men, not including Edward, who went off to war, four of whom were killed. Two of those who died were brothers: William and John Lovell, twenty and twenty-three respectively, killed in March and August 1918. Including Edward, that’s five First World War deaths from one small North London street of eleven properties. Bear in mind how most soldiers’ records from the Great War were destroyed during the Blitz: these are just what I could find in the surviving files.

The war came to visit every street and practically every building. Everyone had a son, a father, a nephew, a godson, a son-in-law, a brother, a cousin at the Front. We all have grandfathers, great-grandfathers, even great-great-grandfathers who served, in addition to the attendant generational strata of uncles. Ordinary men, not heroes; men of whom there’s little of note: they didn’t win medals beyond the campaign ones that everyone received; they weren’t court-martialled; there’s no specific record of any acts of heroism; they were never promoted beyond the rank of private, and they didn’t expect to be. They just turned up, did their duty as best they could, smoked their cigarettes, drank their rum ration and tried to get through it.

Edward’s story isn’t unique. It’s the story of many, the story that’s in your family background as well as mine. Edward is an everyman, his experiences similar to thousands upon thousands of others who left nothing behind, no letters, no diaries, no poems. Yet some of them did leave stories behind. In order to fill in the yawning gaps in Edward’s life and war, it was time to unearth the narratives of his contemporaries, to construct the tale of all the ordinary men in the poor bloody infantry in the name of Edward Connelly. The forgotten soldier, anonymous for the best part of a century, would stand up from the decades of silence and shout on behalf of all the men like him.

I delved into archives, read yellowing letters and leafed through diaries, struggled through regimental histories and watched hours of documentaries. I listened to old recordings made years after the war, old men’s voices from broad Geordie to lilting Sussex burr, occasionally punctuated in the background by the chimes of a mantelpiece clock marking another hour passed since the horror of the trenches. Dead men’s voices now, but in my headphones they were alive, animated, chuckling, emotional, tentative, sad and forthright. Making sure that we would remember as they transported themselves in their minds from silent sitting rooms of china ornaments and antimacassars back to the mud, noise, fear and death of the Western Front. These men had seen what Edward had seen, heard what Edward had heard, feared what Edward had feared, yet they were able to tell their stories and make sure that they could still be told long after their own deaths – and longer still after the events they described.

I’d come to know well men like George Fortune, Fred Dixon, William Dann and the rest in my quest for the life of Edward Connelly and all the other forgotten soldiers.