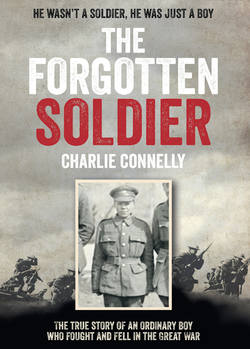

Читать книгу The Forgotten Soldier: He wasn’t a soldier, he was just a boy - Charlie Connelly, Charlie Connelly - Страница 11

5 ‘I was at lunch on this particular day and thought, I suppose I’d better go and join the army’

ОглавлениеWhen war was declared the British Army had just under 250,000 officers and men. They were backed up by just over 300,000 territorials and around 230,000 conventional reservists.

The British Expeditionary Force under Field Marshal Sir John French that crossed the Channel in August 1914 consisted of 81,000 men, including two cavalry divisions. It was, of course, all supposed to be over by Christmas, but by October the first trenches had been dug and four years of attrition on the Western Front were under way. When Christmas arrived there were nearly 270,000 British troops in France and Belgium. By the time of the German Spring Offensive of 1918, the front line, twelve miles long in the autumn of 1914, stretched from the North Sea coast to the Swiss border.

Once the stalemate had been established Lord Kitchener estimated that it could take up to three years to overcome the Germans, a lengthy war for which the British Army was utterly underprepared. He began vigorous campaigns to encourage recruitment in order to build an entire new army. In fact, there would be five Kitchener Armies, mostly comprising six divisions of twelve battalions each.

The initial reaction among the men of Britain was rampant enthusiasm: for one thing, early enlisters were generally able to choose their regiment, hence they could remain with their friends and colleagues, and for another, the wave of patriotism in the light of Blighty going to war washed thousands through the doors of the recruiting offices. Everything was done to encourage men to enlist, from poster campaigns to the creation of the ‘pals battalions’, which were raised in the belief that if groups of men from certain towns or professions could stick together the chances of mass recruitment would be greater. They were right, too: in Lancashire, for example, the Accrington Pals Battalion reached 1,000 recruits in just ten days. The intention might have been admirable, but when entire pals battalions were being all but wiped out (of the 720 Accrington Pals at the first day of the Battle of the Somme, 584 were either killed, wounded or never seen again) it was leaving huge, irreplaceable holes in communities, and the idea was soon dropped.

At first, the enlistment procedure was fairly rigorous compared to how much it would relax later: you had to be between the ages of nineteen and thirty-eight, at least five foot three inches in height and have a reasonable level of fitness. If Edward had tried to join up under-age early in the war it’s likely his partial deafness would have seen him turned away.

The process was straightforward: each recruit was given a brief interview and filled out an attestation form which, when signed by both the recruiting officer and the recruit, committed the latter to serve in the army for the duration of the war. He then swore an oath of allegiance before an officer, underwent a medical examination, another officer countersigned his approval and the man was officially a ‘Soldier subject to the King’s Regulation’. He was given a shilling (the famous king’s shilling) and either handed a railway pass to a training camp or told to go home and await the call-up to begin his training.

George Fortune, born in Dover in February 1899 and the son of a diver at Dover Harbour, was six weeks older than Edward.

‘My father used to say that a man who goes into the army is not fit for anything else,’ he recalled. ‘“Once a soldier, never a man,” that’s what he said.’

George’s father, also called George, worked from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. and walked three miles to work every day, and then three miles home in the evening. According to George the only time his father would take the tram was if he’d been bell diving and come up with the bends. He was a tough, taciturn man and he was tough on his son.

‘I think he was a bit disappointed in me,’ George recalled. ‘He would say, “Give him another basin of sop, we will never rear him.”’

George’s grandmother on his mother’s side was Annie Ovenden from Cork in the south of Ireland, the same part of the country from which Edward’s family had come. His father’s family also had Irish roots and George liked to think of himself as Irish. He was very close to his grandmother and would visit her whenever he could.

‘I used to go straight from school and she’d be waiting at her gate,’ he said. ‘She used to cuddle me up to her and always smelt of snuff and peppermint. Sometimes she used to send me to the pub to get a gill of gin for sixpence: I knew then that Father Laws was coming to see her.’

Although his mother left his father when George was five years old, and his father didn’t seem like the warmest of men, George appears to have had a happy childhood. As youngsters he and his friends would play and bathe by Shakespeare’s Cliff.

‘The trains used to come through the tunnel there from Folkestone’, he recalled. ‘When we heard a train coming, we used to come out of the water and dance, and the old ladies would pull down the blinds.’

Young George even witnessed, practically on his doorstep, one of the great moments from history when, one morning in 1908, he and his brother Walter got up early, walked to North Fallen and watched Louis Blériot make a bumpy landing to complete the first air crossing of the English Channel.

Dover has always been an important place geographically and strategically. The imposing castle still overlooks the town and George was always keenly aware of the military, especially the Navy. The Fortunes lived at Clarendon Place in a working-class area in the west of the town, and one of their neighbours was a naval seaman.

‘Whenever he came home on leave he set the street alight. He would hire a barrel organ in town and park it outside his house. He would have everybody dancing and singing,’ said George.

Soldiers had been a common sight in the streets of Dover since before the Napoleonic Wars, and they were equally visible during the first decade of the twentieth century. One hot day George was drinking from a horse trough on the Folkestone Road when a horse galloped up and arrived next to him.

‘I saw a bundle of khaki on the ground hanging from a stirrup,’ George recalled. ‘It was a soldier who had been thrown from his horse and dragged about a mile.’

It wasn’t all hapless horsemen and innocent mischief, though. On his way home from the cliffs one day George came across the body of a soldier with his throat cut. The boys raised the alarm, but not before George secured himself a souvenir.

‘I took his hat,’ said George. ‘He was in the Buffs [the Royal East Kent Regiment] and I played soldiers with it. My brother Walter told my dad I’d pinched the soldier’s hat but all he said was, “Well, he won’t be needing it any more.”’

Things changed for George a year or so before war broke out when his father was badly injured at work. Going to school one day he’d seen George senior on a tram and, given the time of day and the fact that his father was proud of how he walked everywhere, he knew immediately something was wrong.

‘He was sitting, leaning forward,’ George recalled. ‘He’d had an accident and broken some ribs. There were always accidents and people killed at the harbour. It was dangerous work. He never went back to work at the harbour and I don’t think he got a penny from them.’

George was sent to live with his grandmother while his father recovered. When George senior was well enough he found a job at the local convent repairing boots for fifteen shillings a week. Meanwhile, having been rejected by the navy because his chest measured an inch below the minimum, Walter, whom George looked up to like a hero, joined the army.

Times were hard for the Fortunes and George left school at fourteen for a job as a lather boy at a local barber’s shop. For his 3/6 a week George worked from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., Monday to Friday, and then 8 a.m. to midnight on Saturdays. As well as the lathering, he had to clean the windows, sweep up the hair, clean the copper urns in which the barber heated the water and he even had to clean the boots of the barber’s entire family. He was harshly treated, certainly in today’s terms, but this elicited little sympathy from the elder Fortune: ‘The barber was a little man, about five feet tall, half German, and he was horrible to me. I told Dad about him swearing at me and he said, “It will do you good; you need someone to wake you up.”’

When the war came in August 1914, the talk among the young men of Dover was all of joining up and fighting the Hun. Fuelled by boyish bravado the talk might have been, but George’s friends soon began disappearing to training camps and then to the Front. Still only fifteen years old, George tried to enlist: ‘All the lads were joining up so I tried and said I was nineteen. I was a big boy but I failed the doctor, who said I had a hernia.’

The army doctor referred him to the local hospital for an operation to the remove the hernia, but when he arrived George found the place overrun with wounded men from the Front brought home by ship from Dunkirk. Reluctant to go under the knife, the youngster instead set about making himself useful.

‘The hospital was full and I helped the nurses,’ recalled George. ‘I was in there three weeks and they forgot who I was: I was like a hospital orderly. I had a fine old lark with the wounded men. I used to jump right over their beds for a bit of fun. Then one day the house surgeon was walking round. He saw me and said, “What’s this fellow doing here?” I told him and he said, “Right, we’ll have him on the table.”’

After the operation George was flat out for ten days, in constant pain. No one visited him except a priest, and when he was well enough to leave he had to walk the mile and a half home. Soon afterwards his sister Cecilia, aware of the fractured nature of the Fortune family in Dover since their father’s accident and mother’s departure, took him to London while he recuperated from the operation and found him work with her plumber husband in West Hampstead.

‘Ciss was a godsend to me,’ he remembered. ‘I was ill and she brought me back to health. Then I went to work as a plumber’s mate and I loved the work.’

This fledgling apprenticeship was brought to an end all too soon, however, when George’s brother-in-law joined up and went off to war. George moved on to Highgate to live with his mother and found a job on the Underground. Once settled he wrote to his father but never received a reply – he found out later that his father had emigrated to Australia, taking one of his younger brothers with him. George never saw either of them again.

By 1916 George was working as a gateman at Hammersmith Underground station and living with another older sister, Gladys, whose husband was also away at the Front. Feeling a little like an imposition as Gladys brought up two children in cramped conditions, George decided it was time to try to enlist again and attended the recruiting office at White City: ‘The doctor hardly looked at me this time and I was passed A1. I told the railway and they said they couldn’t keep the job open for me. I didn’t worry much as I was going to be a soldier.’

William Dann, also born in 1899, a couple of months later than Edward, lived along the coast from George in Brighton and would go on to join the same battalion as Edward, the 10th Queen’s (Royal West Surrey). Descended from a long line of Sussex agricultural labourers, William bucked the family trend when he left school at fourteen to be apprentice to a painter named Fisher, who employed him to assist in the painting of brewery vans in red, black and gold-leaf livery. It wasn’t long before the war impacted on William, too.

‘He was a very nice man indeed,’ recalled Dann of Fisher. ‘But as a reservist in the Royal Marines he was called up almost immediately, and we heard he was killed about three months later.’

Like George, all the talk around him was of the war. The army had sergeants walking around Brighton stopping men apparently of military age and asking them pointedly why they hadn’t joined up. One day in 1916 one of them stopped William and, despite being barely seventeen, he decided to go and enlist.

‘I was at lunch on this particular day and thought, I suppose I’d better go and join the army, then,’ he remembered. ‘So I went to the drill hall in Church Street in Brighton, queued up past the sergeant and the policeman on the door and eventually came around to the officers and the sergeant at the recruiting desk. They said, “How old are you?” I said, “Seventeen.” “Ooh, no,” they said, “that won’t do; come back when you’re nineteen.” As I was going out, the sergeant on the door said, “What? You back already?” I said, “It’s no good. They won’t take me.” He asked why and I said, “I told them my age, seventeen.” He looked from side to side, lowered his voice and said, “Well, go and join the queue again and when you get to the front again just say you’re nineteen.” So that’s what I did. Next thing I was sent along to the barracks in Lewes Road for a fitness examination. I came out with an A1 and I was in the army.’

In West Yorkshire, Horace Calvert was another young working-class boy like Edward trying to make his way in the world. Horace was born in September 1899 in Manningham, Bradford, to a father who worked as an assistant to Horace’s grandfather at an ironmongery business on Carlisle Road. Horace was one of six children, four girls and two boys.

‘It was just the usual everyday life of that time,’ said Horace of his childhood. ‘I started going out delivering papers and running errands at the age of nine or ten, anything to get some extra money because there were eight of us in the family and money was tight.’

The Calverts lived in a typical northern working-class back-to-back house. It had a parlour, cellar, kitchen, two bedrooms and an attic pressed into service as a bedroom. There was no hot water, the lighting was gas powered and the toilet was outside, but Horace certainly didn’t feel he had a deprived upbringing.

‘There was plenty to eat because it was drilled into me by my mother to always make sure you had a roof over your head, warmth in the house and food on the table,’ Horace said. ‘I don’t know how she did it but we had meat every Sunday, which lasted till Monday. We managed all right. Clothing was patched hand-me-downs but on Sunday you were always well turned out as far as possible.’

Like his siblings, Horace was sent to Drummond Road School, where he received a basic education that was fairly typical of the times: ‘It was a big school and we were well looked after by the teachers, who were very nice. I learned the three Rs, a little history and we were given talks about behaviour after school hours. We had a concert once a year for the parents.’

At the age of twelve the need to bring some money into the household meant that Horace stopped going to school full time and took a part-time job at Field’s Mill in the spinning department. He’d start at 7 a.m., finish at midday, go home for lunch and then spend the afternoon at school. All his wages went into the household, other than the sixpence he was given every Saturday.

‘I’d buy little toys, pea-shooters, catapults, a bow and arrow,’ he recalled. ‘I had plenty of mates and five or six of us would all go to the local park, but you had to be back for bed by 9 o’clock.’

At fourteen Horace went to work full time in a small engineering shop on Richmond Road in Bradford. His father had wanted Horace to learn a trade and wasn’t keen on him staying on at the mill doing simple manual work as a full-time occupation.

‘The first thing I had to do when I got there in the morning was turn on the gas engine. I didn’t like doing that. Then I used to go to a place called Slingsby’s, where they made handcarts for warehouses. I had to go and collect the wheels, put them on the boring machine and bore them out ready for fitting on the axle and deliver them back to the firm. Also, I had to take out all the filings from the lathes which were then sold as scrap. I kept the floor clean and would go and watch a chap working the machine to see how it was done: it was a good place for training but after twelve months of this I didn’t like it any more. I think it was the dirt and the noise and the running about you had to do. Also, I was on 7 shillings a week; the average wage for a skilled engineer was about 23 shillings.’

Horace, like his contemporaries Edward, George and William, was fifteen when the war broke out, and he remembered it vividly.

‘My father told me there could be trouble among nations because we were being warned in the Telegraph and the Argus about what was happening with Germany,’ he said. ‘The territorials were actively recruiting even before the war broke out so the authorities must have been expecting something. I was interested in the military because we had a quartermaster sergeant in the territorials living near us and I would see him in his scarlet uniform. Also, our headmaster at school, Lodge was his name, was a sergeant in the TA. In addition, I had a friend whose father was in the artillery, so there was always a little link between me and the military. Believe it or not, in those days before the war if people joined the army you thought they either didn’t want to work or they’d got a girl into trouble.’

On 4 August, Horace was up early and on his way to work as usual. When he reached the top of Richmond Road he saw a billboard outside the newsagent announcing in stark black letters ‘WAR DECLARED ON GERMANY’.

‘Even on that day the military was stopping all the horse-drawn vehicles and examining the horses before taking some of them away,’ he said. ‘People welcomed the war in the sense that a challenge had been thrown down over Belgium and they were eager to take up that challenge. That first evening a crowd gathered outside the Belle Vue Barracks and they were cheering every time one of the territorials came out. People were singing ‘Rule, Britannia!’ and all the old favourites outside the barracks. I got so carried away with it all that I stayed there till half-past ten, and I was supposed to be home at nine.’

There hadn’t been scenes like it since Bradford City brought home the FA Cup in 1911. In those early days of the fledgling war, when everything seemed so glamorous and easy, Horace watched the men queuing at the recruitment office at the ice rink near his home on Manningham Lane and was already thinking of joining them. The Bradford Pals had just formed, the rink was their headquarters and Horace liked what he saw (2,000 of the Bradford Pals, incidentally, would be at the Somme and 1,770 of them would be killed or wounded on the first day). Bradford was on a war footing and Horace was up for the fight. Every night when he finished work he’d go to the nearby barracks and glean the latest information from the sentries about the war and all the new recruits until he could contain himself no longer.

‘I was fifteen when I decided to join up. One morning instead of going to work I left my working clothes in the scullery head, went out in my better clothing, walked into the barracks, lined up, the doctor looked at me, I received the King’s Shilling and that was it, all done inside an hour. They never questioned my age – I just said I was eighteen and that was it. I looked at it as a big adventure: I’d read all the stories in the Wide World magazines in the library and it made me want an adventurous life, so I thought this might be more exciting than the alternatives. Otherwise life was just work and a penny to go in the bioscope at the fairground every now and then. I wanted more than that.’

Horace’s enlistment received a mixed reaction at home. As soon as he walked through the door his father, who’d seen Horace’s work clothes hanging up in the scullery, demanded to know where he’d been. Horace informed him he’d just joined the army. There was a pause and his father said, ‘Well, you’ve made your bed.’

‘There were tears from my mother and she said I shouldn’t have done it,’ recalled Horace, ‘but that was it; it was done. I told them not to get me out because of my age or I’d just go somewhere else, like the navy.’

Horace Calvert was going to war.

Fred Dixon came from a slightly less impoverished background near Dorking in Surrey. His father was a draper, although he would die in 1909 when Fred was just thirteen. Born in 1896, he was a little older than my great-uncle in that he was eighteen when he joined up in 1914, but he would come to fight alongside Edward in the 10th Queen’s Royal West Surreys later in the war.

His father’s death had put paid to Fred’s hopes of earning a scholarship to Dorking High School and instead he had to leave at fourteen to become an apprentice to a hosier. Fred didn’t take to hosiery and before long secured a job on the bottom rung of the ladder in the stationery trade. ‘It was rather Dickensian,’ he recalled later. ‘I worked more than 60 hours a week for 5 shillings. I didn’t have a great deal of leisure time either: on Wednesdays, which was supposed to be my half day, I frequently had to catch an early morning train to London to collect special orders and wouldn’t get back until 4:30.’

Despite this demanding work schedule, Fred was able to obtain some basic military training long before the onset of the war, thanks to the lads’ brigade at his local church in Woking. Three times a week he’d walk to the drill hall and learn some basic military skills, and received a medal for his aptitude with a bayonet.

The training and drilling sessions always commenced with a hymn, the highly appropriate “Fight the Good Fight”, with the curate and captain of the lads’ company Reverend Bates at the harmonium.

‘He was over 6’3” and sat at this little harmonium pedalling away, looking as if his knees were under his chin, and we’d all sing lustily,’ recalled Fred. ‘He joined up and later on helped in the forming of Talbot House in Poperinge with Tubby Clayton, which became very famous. He was wounded soon after he got there by a bomb dropped from a German plane over the square, a wound in the foot that ultimately shortened his leg. The bomb killed a girl who was there at the time, too. Tubby Clayton ran over and bandaged his foot for him. Reverend Bates came back from the war, eventually became Canon of Leicester Cathedral and was a very fine man.’

One skill instilled in Fred by Reverend Bates was signalling, which would come to feature very strongly in Fred’s time with the 10th Queen’s. He also learned gymnastics and map reading, and there would be occasional night operations on local commons. They even had a field gun.

‘We used an old muzzle-loading naval gun, with drag ropes like you see on the Royal Tournament on television,’ said Fred. ‘Teamwork was the essence of the exercise as the gun had little value except for display. It was fired on the odd rare occasion, but the last time the gun was taken out onto Horsham Common it was sponged, failed, rammed and then fired again, but it seems the lad who was sponging the barrel got rather excited and didn’t do it properly. When the next charge went in, it was accidentally lit by a spark remaining in the barrel and blew the ramrod out, followed by the hand of the lad who’d been doing the ramming. It probably saved his life when you think about it because the majority of the chaps on the common that day lost their lives during the war. The fellow who lost his hand went on to become the church verger.’

This basic military experience led to Fred becoming among the first to volunteer, enlisting at the end of October 1914 to join a cavalry regiment, something that fulfilled a long-held ambition for him.

‘When I was around four years old, the Surrey Yeomanry had a camp on Ranmore Common, on the North Downs between Westcote and Ranmore,’ he recalled. ‘My mother took me down on a mail cart on the Sunday after they set up camp to see the yeomen. Everything was in apple-pie order when we got there, and it made a deep impression on me seeing these lovely horses and the yeomen walking about in their spurs and riding breeches and uniforms with red facing on the front. Every year after that they’d come through Westcote. My father had a shop on the main road, and I’d stand outside and watch these lovely animals with their shining coats and the men with their spurs, so when the war came it was natural that I’d go into the Surrey Yeomanry, even though I’d never actually ridden a horse.’

At that early stage, however, the ordinary men of England were already seeing through the veneer of cheery optimism that pervaded the posters and propaganda.

‘All over by Christmas, they said. I didn’t believe that, not a bit of it,’ recalled Fred. ‘I said to my mother – and I was only eighteen at the time and a young eighteen at that – this affair isn’t going to be over by Christmas. They’ll have to bring conscription in and I’d sooner volunteer for a regiment of my choice than be conscripted to one I hadn’t chosen. She thought I was quite right. That’s what I did, and I was very glad I did, too.’

Like Edward, Walter Cook was from North London. Born in June 1899, a few weeks after my great-uncle, in Finsbury Park, Walter would go on to become a stretcher-bearer and medical orderly on the Western Front. His father was an electrician and gas fitter, and Walter had five brothers. It wasn’t long till he found his vocation.

‘When I was ten I joined a local Boy Scouts unit and found the first-aid work particularly interesting,’ he said. ‘I managed to get a certificate for it, much to my parents’ amazement.’

Blighted by poor eyesight, Walter left school at twelve, even though he wasn’t really supposed to: ‘They didn’t bother with me much. My parents knew the local school inspector well and he liked a drop of the parsnip wine my mother made. One day he came round and it was agreed I’d be better off finding odd jobs than going to school.’

Also like Edward, Walter had a family connection to the military, and the Boer War in particular. His mother’s brother was a regular soldier who’d fought in South Africa and would occasionally visit and entertain the Cook brood with tales of his exploits and adventures. When the First World War was declared, Walter’s uncle Robert was one of the first to go.

‘When the war started he did pay a visit, and I heard him say he was hoping to go to France very shortly,’ Walter remembered. ‘We liked him, us kids. He drew sketches for us and always seemed to have a joke or a funny story at his fingertips.’

Once he’d left for the front, the Cooks heard little of Robert until January 1915, when he came home wounded and a changed man: ‘He came back with a limp and we learned that many of his men of his men who’d been wounded had to be left lying where they were. It was the retreat from Mons, where there’d been many casualties and not nearly enough stretcher-bearers. The fighting had been so fierce and the guns so lethal that going back for the wounded was almost out of the question. He was very glum, thinking about the men they’d had to leave behind for want of a stretcher. That caused me to think a little. That night I went to bed and thought that knowing a bit about first aid I might be able to enlist and help – if I could get past the recruiting officer.’

The next day Walter presented himself at the church in Tollington Park, where he’d once been a choirboy, whose hall now served as the local recruiting office. He joined a long queue of volunteers and, producing his first-aid certificate from his time in the Scouts, declared his intention to join the medical service – while also adding the small matter of two and a half fictional years to his age.

‘The doctor quizzed me in a manner that made it clear he doubted my age,’ he said. ‘But my desire to go and help those fellows lying wounded on the ground was so great I considered it a risk worth taking. I pulled it off and was assigned to an ambulance unit. I didn’t tell my family until I’d joined up. They’d always known that if I made up my mind I’d carry it through, so they knew there was little point in protesting.’

I have no way of knowing exactly when Edward enlisted, or even whether he was conscripted, as his records are among those lost in the Blitz. He turned eighteen in April 1917 and might have tried then. He might have tried earlier, like the rest of the lads already mentioned, but been turned down for whatever reason, possibly the deafness cited on the 1911 census.

He might have waited to be conscripted. For all the razzmatazz and rush to enlist in the early years of the war, once word filtered back of the terrible things happening and the enormous numbers of dead, the recruitment of volunteers began to tail off. In August 1915 a national register was taken, a sort of supplementary census, to give the government an idea of just how many men of military age were in the country, and of those how many were fit and willing to volunteer. The results were not particularly encouraging. In January 1916 the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, proposed the Military Service Act, in which unmarried men or widowers aged between eighteen and forty-one without children or dependents (the act immediately became known as the ‘Bachelors’ Bill’) would be required to join the fight. It wasn’t an immediate success: in the first two months, a quarter of the nigh-on 200,000 men who had been sent call-up papers simply failed to show up. Serving soldiers were sent to large gatherings, like football matches and busy railway stations, to buttonhole men apparently of military age in the crowds and find out whether they’d been avoiding the call. Even with these measures, in May it was deemed necessary to extend the bill to apply to all men between eighteen and forty-one, married, single, widowed, whatever. Later in the war, the high number of casualties and the need for new recruits was so great that in February 1918 the upper age limit was raised to fifty, and the law specifying that a recruit could not actually participate in the war until he turned nineteen was relaxed.

It may have been Edward’s youth and deafness that kept him from the front earlier if, as I suspect, he didn’t see action until the spring of 1918. The medical examinations varied in their rigorousness at different points of the war. In the early days the doctors were paid a shilling for every man passed but received nothing for a man deemed unfit for service, so the temptation to err on the side of enlistment must have been great. Under conscription, however, the doctors were paid a flat rate and a three-tiered system of fitness was introduced. An A grade meant a man was fit for general service, B meant he was fit for service abroad but in a support capacity, while C designated a man fit for service at home only. Each category was then given a grade between one and three, one being the strongest. By the end of 1916 this system meant that only 6.5 per cent of new recruits were rejected as completely unfit for service, but as the war went on, and the need for more and more troops grew, a greater laxness crept into the system. When murmurs of public disquiet began about the apparent weakness of some of the troops being packed off to the Front, things were tightened up again in 1917.

If the accounts in this chapter are anything to go by, Edward would have been keen to sign up. For one thing, for a boy from a poor background with a pretty rotten job, the army would have been an appealing prospect in many ways. It was a career, a steady job, soldiers were well fed and the money wasn’t too bad: a private earned a shilling a day, with an additional penny for every day spent in a war zone (raised to 3d a day in 1918), a little better than George Fortune’s 3/6 a week for those long hours at the barber’s shop and Fred Dixon’s 5 shillings a week as a stationer’s runner.

At the same time, however, Edward would have had some idea of the horrors taking place on the fields of France and Flanders. His uncle had been killed. Many of his contemporaries from Admiral Place had gone to war; a few of them were never coming home. At this distance it’s impossible to know what Edward’s motivations or reservations would have been but, whether he was called up or volunteered, he entered the army at the age of eighteen, and I strongly suspect that he was first sent over to Flanders in the spring of 1918 once the law regarding nineteen-year-olds was relaxed. The 10th Queen’s had suffered heavy casualties in the German Spring Offensive and they needed to make up the numbers fast. One account of the 10th Queen’s mentions the arrival of ‘a load of nineteen-year-olds’ as new recruits around that time, and when the National Archives made the wills of soldiers available in 2012 I found Edward’s, made on 2 April 1918, three weeks short of his nineteenth birthday.

If the accounts above are anything to go by, there was no sense of fear among the young lads at enlistment. There was just a feeling that it was something you had to do, something that got you out of the routine of industrial life, something that promised adventure and something that made you feel that you were genuinely contributing to the war effort.

Enlisting was only the start, however. The next step was to turn these youngsters into soldiers. Meanwhile, I was trying to turn myself into a walker.