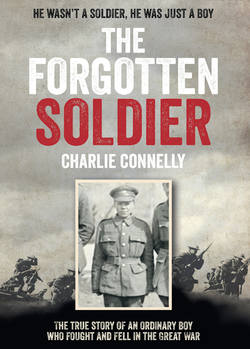

Читать книгу The Forgotten Soldier: He wasn’t a soldier, he was just a boy - Charlie Connelly, Charlie Connelly - Страница 13

7 ‘In the event of my death …’

ОглавлениеBasic training for new recruits took place in Britain, either at an established camp like Aldershot or Shorncliffe, near Folkestone, or one of the many new camps that sprang up as the war progressed. Initially, the emphasis was on getting the recruits fit, teaching them about their equipment and how to use it, and instilling discipline. For most of the new lads this was a completely alien way of life: the endless drills, the constant cleaning and polishing of equipment, how to salute a superior officer correctly, how to dig a trench and the route marches of up to twenty-five miles with a fully equipped pack. They were given a number, a haircut and a uniform, as the army set about stripping them of as much of their individuality as it took to make them into fighting and killing machines.

On arrival there was another, more rigorous medical for which the men had to strip naked and wait in line to see the doctor, who would prod every limb, check the pulse, examine the teeth and test eyesight and hearing.

The new recruit was then given his basic kit: two tunics, two pairs of trousers, an overcoat, a cap, a pair of boots, three pairs of socks, two pairs of underwear, three shirts, a set of cutlery, a mess tin, a razor, toothbrush, shaving brush, shoe brush and a needle and cotton. With the kit the quartermaster handed the new man some string and brown paper: civilian clothes, the last link to a previous life, were to be wrapped up and sent home.

One of the positive aspects of camp life was the three meals a day, something men from poorer backgrounds would not have been used to. Breakfast consisted of bacon with kippers or a slice of bread and a mug of tea. Lunch was pie, stew or boiled beef and potatoes, while at tea time you were provided with bread and jam and more tea. The helpings were not enormous, and with all the relentless physical exercise the younger recruits were often hungry, meaning they were thankful for the recreation huts set up by churches and voluntary organisations where the lads could go to sit in the evening with a cup of tea and a bun.

George Fortune was sent initially to Hounslow Barracks with the Royal Fusiliers but then moved on to Aldershot with the Middlesex Regiment, where he was soon given a taste of what military life had in store.

‘When we arrived at Aldershot we had to parade at the gym for a lecture from the adjutant,’ said George. ‘He was a little man, I think he was Jewish, name was Lewis. He jumped up on the platform and shouted, “I’ll break your hearts!” Someone wrote to John Bull about him and in the article he was referred to as the Khaki Heartbreaker.’

In order to build up fitness, George and his colleagues were marched constantly around the square in all weathers in a training regime that bordered on the brutal: ‘They would have us up at five in the morning, shaking blankets out on the square, then for the rest of the day they drilled the life out of us. Our hands used to be at our sides. The weather was freezing and I got bad chilblains: my hands were like sausages and the chilblains were broken too. Waiting for pay outside our barracks one day Sergeant Watts – he was a real snaggle-toothed bastard – came up to me, barked, “Take your hands out of your pockets,” and slashed at them with his cane. I was a bit slow getting them out as they were so sore. When I hadn’t whipped them out as quickly as he’d liked, he asked me my name and told me to fall in once I’d got my pay. When I went to see him he made me clean metal washbasins with sand. The water was ice cold and the sand got into my broken chilblains, and since 1919 I’ve been looking for that bastard. It’s not too late to kill him.’

William Dann’s experience of his basic training was altogether less unpleasant. After enlisting, he was billeted at home for six weeks and drilled at Preston Park in Brighton before being sent to Canterbury where he was transferred to the 10th Queen’s as an infantryman.

‘The training I thoroughly enjoyed,’ he said. ‘It was so exciting with plenty of interesting things to do. The discipline was a bit tight, but you could take it – that’s what you went in for. After a while at Canterbury we were transferred to Colchester Barracks, which was an infantry barracks. The officer shouted at parade one morning, “All men under nineteen remain and the rest dismiss.” They gave us all a form and a railway warrant home to get our parents’ permission to go to France, even though we were still under nineteen. I went back to Brighton and my father and I had a chat. He asked me if I wanted to go and I said, “Well, I’ve been with these chaps a long time and I know them. If I don’t go I’ll have to make new friends, so I think I’d rather go.”’

William Dann was going to France. Meanwhile Fred Dixon also found himself training at Canterbury, working with horses: ‘We had the stiffest training with the 6th Dragoon Guards at Canterbury. It was the dragoon depot down there and we came under the instruction of the peacetime sergeants, who were a tough lot. They tried to impress upon us what a subhuman breed we were; if they set out to break our hearts they didn’t succeed, but it wasn’t for want of trying.’

The recruits were roused at 5:30 a.m. by a bugler playing ‘Reveille’. Not only was this to wake the men, it also told them that they were required on parade fifteen minutes later washed, shaved and clad in shorts, singlets and plimsolls. After parade they’d be given breakfast and sent on a four-mile run, at the end of which they were required to clear a succession of horse jumps. Finally they were sent into the stables.

‘That’s when Sergeant Jock Simpson entered the arena, bade us good morning in an appropriate fashion – “Now then you bloody shower of bastards” – and had us commence the mucking out,’ said Fred. ‘This consisted of removing the horses’ bedding with our hands and taking it outside to dry off and use again. The sergeants were very particular about us removing every piece of straw. Then grooming and feeding followed, then the cookhouse rang – no time to wash our hands – then we dressed for parade, then the real ordeal of the day, a terror: one hour in the riding school, much of the time without stirrups. At the end of the hour we’d emerge from the school sweating, with grimy faces, dusty uniforms, and the horses were all white foam.’

In Bradford, Horace Calvert was also commencing his basic training. At first he was billeted at home, reporting to Belle Vue Barracks every morning to parade and drill from 9:30 until lunchtime. After a week he was given a uniform, and a week after that their rifles arrived.

‘We got a khaki jacket, then trousers, socks, puttees, heavy marching boots, cap, badge, brass numerals for our shoulder straps and a greatcoat, but no other kit because we were still living at home,’ he recalled. ‘Puttees came with practice, till you knew exactly how many turns there were on each leg. They were awkward, but they supported you. Much better than thick stockings in that respect.’

As a change from the parade ground, twice a week Horace and the other recruits would be marched through the town as a recruiting exercise. Men intending to join up were encouraged to fall in behind the unit and follow them back to the barracks to begin the process.

‘Sometimes there’d be twenty or thirty behind you,’ he said. ‘Some lined up because of drink, I’m sure. We definitely seemed to bring in a few when the pubs had shut in the afternoon. The crowds all clapped and cheered: I enjoyed it and I was proud. The other recruits were very friendly and you’d all help one another.’

Being an underage recruit did have its drawbacks, however: ‘At that time King George V had made it known that he liked all members of his household brigade to have a moustache, so the chaps all grew one – but I couldn’t. I was only sixteen and hadn’t started to shave yet. I tried to start shaving, and using a razor, but nothing was happening. I even got extra fatigues, peeling potatoes and what have you, for not growing a moustache, but I took it all in good part.’

Victor Fagence, a farmer’s son from Surrey, had volunteered almost reluctantly for the 10th Queen’s in December 1915, a few weeks before the first conscription bill was passed. He was eighteen years old.

‘There were pressures on me, such as how all the young men around my age had joined up, but I was rather fed up with things in general,’ he remembered. ‘Eventually, I thought, Well, I’ll have to go in the army before long anyway so I might as well join up rather than wait for the Conscription Act. I was posted to the 10th Queen’s at Battersea, given six days’ leave before I had to report and then reported a few days before Christmas at the battalion headquarters at Lavender Hill. I gave them my papers and was measured up for my uniform. By the time I joined, the war had been on about sixteen months and the uniform suppliers were better than they had been in the early days. It wasn’t made to measure but I was fitted out pretty well.’

The 10th Queen’s would train in Battersea Park with a similar intention to Horace Calvert’s marches through Bradford: to encourage others to enlist. They’d have squad drills, bayonet practice with straw-filled sacks, and marching in column, but the effect seemed to Victor to be negligible: ‘People would watch us train in Battersea Park but by then everybody was used to seeing troops and soldiers everywhere so we were nothing special.’

In January 1916 the battalion moved on to Aldershot, where they learned skills that would come in useful but couldn’t really be indulged in Battersea Park: trench digging, sandbag filling and the laying of barbed wire. It would be a while, though, before Victor could use those skills in earnest.

‘The government had given a pledge that no man under the age of nineteen would see active service,’ he said. ‘But I think with me it was discovered by accident that I’d put a year on my age when I joined. So, when the 10th went to France in May 1916, I was sent to the 12th Battalion in Northampton, a reserve battalion.’

Alan Short from Bromley-by-Bow in East London was born a month after Edward, in May 1899, the son of a lighterman on the River Thames. He left school in 1914 and worked at the Joseph Rank flour company, in Leadenhall Street in the City of London, and had experienced the reality of the war when the first boy from his local church had been killed in May 1915.

‘Alfred Ernest Crawthorne. He was older than me but he was a friend of the family,’ said Alan. ‘He’d helped carry me around the playground to celebrate my elevation to the main school from junior school. He was a very nice man. I knew his two brothers and they took it hard. The families were more or less left to fend for themselves. One conveyed one’s sympathy but there was no spare money in the community to support them.’

After losing his job in a dispute over wages in January 1917, Alan decided to join up, despite still being four months short of his eighteenth birthday: ‘I went to Stratford in East London. I didn’t want to be called a conscript; it indicated that you weren’t too keen on going. I knew that I was approaching military age, when I could be called up, so I just went myself. I sat there, was called forward, signed forms to join the service for the duration of the war, took the oath of allegiance and got a shilling, which I immediately went out and spent on riotous living.’

Alan was called up to the Training Reserve, a battalion of underage boys that were given a year’s training in England before they could go out to the Front. With his friend Ernest Moyes he reported to Horse Guards Parade, where they joined around fifty other boys and marched to Paddington Station. From there, they were taken by train to Sutton Veny Camp, near Warminster.

‘The others came mostly from East London too, and some of them were already pretty tough,’ he said. ‘There were huts for about thirty men at a time. Your bed was a low trestle, three planks, a short mattress and pillow, and a couple of blankets. After “Reveille” they were packed up and your mattress had to be folded over, all very regimental. The inspections were pretty thorough – they even insisted you had no mud between the studs on your shoes.’

Like most of the youngsters hoping for a bit of adventure, Alan found the monotony and routine of camp life took a little getting used to: ‘The day would start at 6, and if you were struggling to get up the sergeant would tip your bed up and out you’d get. Then you folded up your mattress and dry-scrubbed your floor with a short-haired brush. Breakfast was mostly bread and butter and tea. I don’t remember any bacon and eggs … Then there’d be training till lunch, and my favourite was a lovely meat pie with a soft thick crust: the quality was good. Then there’d be more training. I found the constant drilling a bit boring, but it meant you learned to stand to attention and obey commands. We learned how to throw bombs too – you got the bomb, pulled the pin out and threw it round arm. I could manage about thirty feet. The bombs were about the size of your hand and were quite comfortable. There were a lot of accidents but I was never nervous with it. Some of the fellas were, but if you followed instructions you were perfectly safe. If a man did a thing wrong they’d call him this, that and the other. It upset me in the beginning but you got hardened to it.’

Basic training was usually completed in around six weeks and, depending on the state of the war and how urgently recruits were needed at the Front, full training could last anything up to five months.

Eventually, the new recruits would receive word that they were to be sent over to France, at which point they would be issued with their combat kit: a steel helmet, body belt, field dressings, gas mask and ground sheet, goggles and vests.

It was around this time that the soldiers would make their wills. If the nerves and the cold, creeping fear of impending departure hadn’t done it, and if the last vestiges of glamour, flag-waving crowds and cheers had not been battered out of the men by the relentless drilling, being handed a folded piece of paper marked ‘Informal Will’ and told to complete it would have been the final realisation that this was actually happening. They were going to war and there was a strong chance they wouldn’t be coming back.

When the British Probate Office made thousands of soldiers’ wills available online in 2013 I managed to find a scan of Edward’s, one of the saddest documents I’ve ever seen. It’s in his handwriting, controlled and well-practised, if slightly spidery, and it’s dated 2 April 1918, seven months almost to the day before his death. There isn’t much space on the single sheet, and the writing bunches up a little towards the bottom of the page where he’s signed and dated it, with his rank and regiment, but it’s clear and coherent:

In the event of my death, I leave my War Savings Certificates to my goddaughter, Miss Lily S Hill of No. 6 Spencer Street, Southall, and £2 to my grandmother Mrs Christopher, No. 5 Branstone Street, N Kensington, the remainder of my money and effects going to my mother, Mrs G. Connelly, No 6 Branstone Street, N Kensington.

And that’s it. That’s all Edward Connelly seems to have left behind of himself: fewer than fifty words of right-sloping handwriting, conventional in its well-practised flourishes and loops, and clearly carefully thought out. I wonder where he was when he wrote it. Surrounded by similar lads to him, the George Fortunes, Fred Dixons and Horace Calverts, sitting on their beds hunched over these flimsy pieces of paper following the guidelines they’d been given as to what to write?

‘In the event of my death …’ What a thing for an eighteen-year-old to have to write, miles from home in a strange place, in an unreal world of drills and orders and bugle calls and bomb-throwing practice. How he must have longed to be at home among those familiar cramped streets, still just yards from where he was born, and see his mother and father and grandparents again. Instead he had to prepare to sail for a foreign country, departing Britain for the first time a matter of weeks after leaving Kensal Town for the first time.

As he thought about the event of his death, he thought about his goddaughter, his grandmother and his mother, arguably the three people closest to him in the world. He didn’t have much to leave, a couple of quid, some savings certificates and the odd few coins and bits and pieces, but he shared them out thoughtfully. That was his legacy, all he had in the world.

(Lily S. Hill, incidentally, wasn’t dealt much of a better hand by fate than her godfather. Barely a year old when Edward was making her the first beneficiary of his will, Lily married in March 1937 but within six months was dead from a lung abscess.)

The image of all those young lads, lined up in regimented rows, sitting on their bunks, hundreds of them, all just setting out in life, not even having got to grips with the world yet, not even having discovered who they are, is a powerful one; all of them hunched over like khaki-clad beetles, concentrating, making sure they used their best handwriting as they formed the words, ‘In the event of my death …’