Читать книгу In the Company of Rebels - Chellis Glendinning - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIV. MAKE LOVE NOT WAR: BERKELEY IN THE ‘60S

LET’S TAKE THE PARK!

—DAN SIEGEL, PRESIDENT, ASSOCIATED STUDENTS UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, MAY 15, 1969

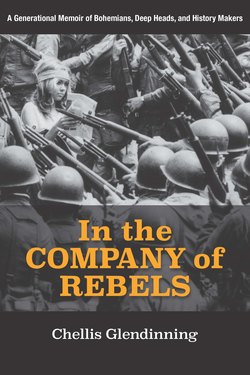

A protester against the shutdown of the communal People’s Park in Berkeley—in captivity. Photo credit: Ted Streshinsky. Courtesy of the film Berkeley in the Sixties ©1990.

THE DEITIES WERE WATCHING over my generation. An acquaintance from Cleveland who was studying at Amherst College—and would soon mutate into a rabid Communist Labor Party militant—said to me, “There’s something going on in Berkeley that has to do with our generation. You need to go.” The remark sunk in, and just a few days before my twentieth birthday, I threw work shirt, sandals and jeans into a little suitcase, bought a $75 plane ticket from Cleveland to the Bay Area, and made my break.

In 1967, Berkeley was a hub of youth culture and New Left politics—and was located right up Telegraph Avenue from Oakland, where the Black Panther Party was in gestation with its objective of protecting their communities from police violence via its own armed patrols. This was the first place inside the U.S. where I witnessed a flourishing street life, and indeed one of my first observations, at Moe’s Books on Telegraph, was how earthy, alive, and laid-back everyone seemed. Old jeans. Navy bellbottoms. Men boasting ponytails. Women in Mexican peasant blouses. Espresso and Gauloises. I heard jazz musicians and 1930s commie pinkos airing their radical sentiments on listener-sponsored KPFA-FM. Mario Savio from the Free Speech Movement was the postman. Richard Brautigan was penning his fish stories up in Bolinas; Julia Vinograd, her street poems at the Café Mediterraneum. Richie Havens belted out “Freedom” in the university’s lower plaza. The Free Clinic was overflowing with patients, the Free University with students. Books, books—everyone was devouring books. Karl Marx and Carl Jung. Anaïs Nin. Malcolm X, Eldridge Cleaver, Frantz Fanon. Wilhelm Reich. Simone de Beauvoir. Sylvia Plath. Allen Ginsberg.

I arrived in mid-June, and the tang of the 1966 Oakland Induction Center confrontation with the police lingered like Ripple wine on the tongues of the anti-Vietnam War activists. I found an empty apartment where the landlord let me crash gratis for the summer, got a morning job as a governess, bought a near-see-through dress made of burlap, hitchhiked from Berkeley to L.A., marched with Clevelander Dr. Benjamin Spock at the Century City anti-war demo, and when I took my first drag of marijuana, I saw satyrs galloping through the air. By September I filled out the forms to transfer from Smith College to the University of California, Berkeley.

Activist couple in the 1960s—expressing both their politics and their alternative way of life. Gratitude to the now-defunct Berkeley Tribe (1969–1972), which was more radical than the community’s original underground newspaper, the Berkeley Barb. Vol.1, No. 6, Issue 6, August 15, 1969.

When I got back to Cleveland to collect my things, my mother invited her movement friends to hear me talk about what strange goings-on were erupting in California. I was just delivering my analysis of the Beatles song “All You Need Is Love” when one mother, nearly quaking in fear, asked, “But, but … isn’t Berkeley just a big cesspool of sex, drugs, and radical politics?” I paused for a long moment, discombobulated by the alarm in her voice. I hadn’t really thought of it that way.

Finally, all I could do was answer: “Yes.”

MARTY SCHIFFENBAUER: MASTER OF POLITICAL INVENTION

(1938–)

I was so unhip, I didn’t know Berkeley was hip.

—M.S., LETTER TO CHELLIS GLENDINNING, 2014

I had never been to a real health-food store before. Of course, what with being in Berkeley, I had already been introduced to Adele Davis’ food theories, and encouraged to use whole-wheat flour, make my own yogurt, and drink herbal tea. And I’d heard of the Food Mill. At the time—before Wholly Foods opened its doors at Shattuck and Ashby and while the industry remained but a twinkle in the eyes of a few health-food-freak entrepreneurs-to-be—the Food Mill was the Bay Area’s only outlet selling organic grains, seeds, and flour.

But I didn’t know where it was.

Marty said he would take me. Imagine my awe when he pulled up to the Vine Street commune in a 1963 Chevy II … convertible. To my mind, the car presented a sharp quip of a lampoon of the American Dream our generation was rejecting and, at the same time, was utterly camp in its own right. Off we went—Marty in his trademark shorts and combat boots, with his flaming red corkscrew locks flying in the wind like Gorgonian snakes; me in U.S. Navy bellbottoms, purple Hindu shirt, and long brown braids—cruising along the Eastshore Freeway, past the driftwood/cast-off machinery sculptures constructed anonymously in the mudflats and on to Oakland’s MacArthur Boulevard.

In those days it was a good bet you would find all five feet and four inches of Marty as a very tall presence around the political advocacy tables in Sproul Plaza. He was a bit older than most in the anti-war movement and, before the 1974 stock-market collapse, he made his living by buying and selling stocks; it was a feature that I found incomprehensible but also far-out—and that definitely made him the All-American Hippie Weirdo Drop-Out. That he filled his studio apartment with God’s Eyes he crafted himself only enhanced my view. Marty kept his Gorgon hairdo for near a lifetime, although it did change color as the years ambled onward; he wore the shorts and boots until the late ‘70s, when they finally disintegrated and he switched over to athletic get-up. I was standing in front of the Café Mediterraneum on Telegraph Avenue when the tornado of red hair and gym shorts arrived, bubbling over with endorphins and the discovery that if he ran just three miles every day, he could eat all he wanted!

Marty grew up in Brooklyn in the apartment behind Berdie’s Corset Shoppe. His parents, Berdie and Morris Schiffenbauer, raised him Orthodox Jewish, sending him to yeshivas and keeping the Sabbath every week. “My parents were not very political,” he reports, “but they loved FDR and always voted Democrat. They were, of course, pro-Israel. Mostly their politics were of the Whatever-Is-Good-for-the-Jews variety.”

Marty in his Berkeley commune, 1972. Courtesy of Marty Schiffenbauer.

He first came to Berkeley in 1964, tooling up University Avenue in his Chevy II almost by happenstance. He liked the summer-blue sky, he liked the vibes, he liked the slender blondes—and in his own pre-anti–Vietnam War way he was escaping the draft. In 1962 Marty had opted to join the New York National Guard as the least demanding way to serve his military obligation. By his own admission, he survived six months of active duty but found the subsequent weekly meetings a drag on his time and on taxpayers’ money. Presaging the political expression that was to fill the rest of his life, he wrote a scathing letter to the New York Times. The captain of his reserve unit happened to read it, freaked out, and proposed that Private Marty move to another state immediately—and one preferably far away. Marty then stumbled upon a summer course in German at UC Berkeley that would satisfy the language requirement for his Ph.D. in experimental psychology at NYU, and voilà! off he went.

By 1967, having completed the bulk of his coursework for the Ph.D., he made the definitive move across country. He launched his political involvement in October Berkeley-confrontation style by joining thousands of others in front of the Oakland Induction Center during Stop the Draft Week. His personal approach, though, did not resemble the serious, organized assemblage of the marchers who had faced down the no-nonsense Oakland Police’s Flying Wedge with improvised shields made of garbage- can lids, tire-fed bonfires, and parked cars as barricades. Marty called for a far wackier, Yippie-style Naked Noisy Vigil for Peace. In truth, no one came nude, but a local character named Jefferson “Fuck” Poland showed up strutting nothing more than a jock strap.

Marty was obviously attracted, then, to the Gray-Life Tour of the Suburbs. I was too. This ingenious mirror image of Grayline’s tour for suburban people to come to Berkeley to observe the hippies was the invention of the Berkeley Barb’s military correspondent, Lee Felsenstein. As if in a zoo, you would be leaning against the steps to Sproul Hall discussing the Camus-Sartre breakup or the nutritional value of alfalfa sprouts or LBJ’s role in the escalation of the Vietnam War, when one of these suburban tourists would bold-facedly situate him/herself smack-dab in front of you and rob your soul with a Kodak Brownie. Ergo, one Saturday morning in 1969, two busloads of us (packing Kodak Brownies) veered off the map to Walnut Creek and environs. When we downloaded ourselves to check out the sights on one quaint little Main Street, the terrified storekeepers and restaurant owners bolted their glass doors and pulled down their corrugated metal security gates so fast they looked like dominoes crashing down across Southeast Asia. Next stop was a park. Here I got dizzy watching children riding around a pony-giraffe-turtle-festooned carousel, while Marty was approached by some steak-fed teenagers who saw in his wild tresses their possibly best-ever customer; they tried valiantly but unsuccessfully to sell him the acid and marijuana they normally peddled to their high school peers.

In psychedelic style, the poster for the Naked Noisy Vigil for Peace, 1968. Designers: N. Pettitt and Marty Schiffenbauer. Courtesy of Marty Schiffenbauer.

The tour was capped off with a visit to the straight people’s retirement community, Leisure World. Needless to say, our buses were refused entry to its clipped green lawns and croquet courts, so we hurled our bodies upon the forty-foot erector-set sculpture of planet Earth outside the gate and, freaks hanging from Somoza’s Nicaragua and Franco’s Spain, flew around and around as the giant globe spun.

Sign of the times: I was at Marty’s on Haste Street when the Symbionese Liberation Army crashed and burned in the biggest police shootout in U.S. history. The SLA had first hit the news in 1973; they took down Oakland’s popular African American school superintendent Marcus Foster with cyanide-packed bullets for what they misunderstood to be his “support” of compulsory ID cards. (He was, in fact, against them.) They rose up into the public eye again in 1974 when they kidnapped publishing heiress Patty Hearst and her betrothed, Steven Weed, in Berkeley. Now, via the new compact cameras and mobile units, all three TV stations were live-casting the defense of their L.A. “safe house.”

The SLA appeared to be part of our movement—anti-war, anti-racist, calling the nation’s jails “concentration camps” for Blacks. Yet they were different from us for their tactics. This ill-prepared army fancied itself as a self-styled, left-wing revolutionary band and the vanguard of urban guerrilla warfare à la Regis Debray and the Uruguayan Tupamaros. But, as Marty put it, they were nothing but “a violent cult with an egomaniacal leader.”

Now, on May 17, 1974—better known to us as the day after Marty’s thirty-sixth birthday—the Los Angeles police and fire departments, FBI, and California Highway Patrol were closing in on them. And now, instead of merrily toasting the birthday boy and chowing down on organic carrot cake, we were fixed like the stelae of Stonehenge around the tube. I was too dumbfounded to speak. The men’s voices rose and fell in gasps of revulsion as each round was shot and returned, as some inside attempted to break away from the house and were met with law-enforcement gunfire, as the place burst into devouring flames.

For Marty the symbolic protest of street theater gave way to direct action in 1971 when he founded the Berkeley chapter of War Tax Resistance and, applying his expertise in financial matters garnered from playing the stock market, counseled people in federal tax refusal. As the raucous ‘60s faded from view, he continued to ride this new arc of political action, taking on an issue that would affect all of Berkeley: rent control.

As a long-time tenant, he joined with the city’s varied housing organizations as well as its outraged renters—and gave the effort his all. He helped write the bill that in 1972 would make Berkeley the first U.S. city to impose restrictions on unrestrained rent increases and landlord evictions for actions not considered “just cause,” while requiring landlord payment of interest on security deposits. In 1976 the California Supreme Court under Chief Justice Wright handed down a landmark decision: he granted victory to the basic principles of rent control, including the right of municipalities to enact their own legislation. At the same time, though, the judge invalidated the Berkeley initiative for its procedural favoring of renters at the expense of the rights of landlords. Ergo, in 1978 Marty and others drafted a new rent roll-back ordinance mandating that eighty percent of landlord property-tax savings be rebated back to tenants as rent reduction. It was approved by the voters. Emboldened, Marty and his allies wrote a comprehensive ordinance in 1980. It too passed. Marty was elected to serve on the first Berkeley Rent Board, and thirty-plus years later the legislation is still in place. Marty is sometimes called the Father of Rent Control, although he likes to clarify by saying: “Well, maybe … but I was not a single parent.”

Rent control easily morphed in his mind into a proposal for limits on house-sale prices. This new wrinkle was formulated in 1989 during a morning run with a friend; the two were kibitzing about skyrocketing prices that divided citizens into the landed class and the forever-renting peon class, thus driving minorities and senior citizens from the community. To Marty, an increase in sale price calculated at the national average of six percent of original cost would be more reasonable and just than the typical increase in chic Berkeley that, in one year, had shot up by thirty-five percent—making a $150,000 home sellable overnight at $202,500. Marty’s jogging partner revealed the idea in his weekly East Bay Express column and from there it went viral, appearing in the San Francisco Chronicle, Wall Street Journal, and various venues of the national press. Alarm also went viral, with Marty’s progressive friends pronouncing it too radical, and one Berkeley politician withdrawing for fear that her career would go belly-up for association with its “Father.” A co-author of the rent-control bill, attorney Myron Moscovitz, proclaimed in a 1989 San Francisco Chronicle article, “I don’t think the proposal has a snowball’s chance in hell.” Marty also began to receive hate mail, death threats, and answering-machine messages like “You are scum” and “Schweinhund.” His response: “We’re living in a democracy, and this can be voted on. They don’t have to kill me, sue me, or leave hate messages.” Just the same, he pulled back.

Walking his talk as a housing activist, Marty lives now in a one-bedroom apartment in the Parker Street Co-op that a collective of twenty-four households formed in 1991. A splendid side effect of going on TV to hype the house-sale proposal was that an old acquaintance, a woman he had once dated, saw the show and called him up. They began what has been, so far, a thirty-plus-year love affair culminating in their 2011 wedding, although—true to form of the inventiveness Marty is known for—they still live in their separate pads. In his, over the kitchen sink, he boasts an R. Crumb cartoon of the infamous 1960s bearded sage Mr. Natural proudly washing dishes. And, indeed, the man “Keep(s) on Truckin’”—as of this writing, launching another controversial campaign, this one to raise Berkeley’s minimum wage.

Among those Bohemians, rebels, and deep heads who pursued higher education, the magnifying glass that renders focus to their lives might reveal a vision gone wildly askew in regards to the field in which they majored and what they ended up doing. But as you will see in coming chapters, when all is said and done, Marc Kasky, with his master’s in urban planning, indeed spent his life practicing city planning—just in a non-conventional way; while economics major Jerry Mander ended up warning people about the dangers posed to democracy and environment by the corporate-dominated global marketplace. Marty too: though he never held a “real” job in his chosen field, his offerings surely magnify the realm of … experimental psychology.

TOM HAYDEN: POLITICAL ANIMAL

(1939–2016)

From SDS to Occupy Wall Street, students have led movements demanding a voice. We believe in not just an electoral democracy, but also in direct participation of students in their remote-controlled universities, of employees in workplace decisions, of consumers in the marketplace, of neighborhoods in development decisions, family equality in place of Father Knows Best and online, open source participation in a world dominated by computerized systems of power.

T.H., “PERSONAL STATEMENT: FIFTY YEARS LATER, STILL MAKING A STATEMENT,” THE MICHIGAN DAILY, 2012

Forty-some years after the fact, round about 2005, I had the chance to tell Tom Hayden that back in the ‘60s when he lived in a Berkeley commune called the Red Family, I had had a mad crush on him. The truth is I fell into infatuation the moment I heard his voice on KPFA-FM reading the text of his 1962 Port Huron Statement that laid the basis for the peace-justice-equality movements of the 1960s. But it wasn’t until the later ‘60s that he moved to Berkeley. His arrival—much-touted in Bay Area political circles—was almost too much for my twenty-one-year-old hormones to handle. I attended a teach-in on Canada-bound draft avoidance so I could look at him. But there sat his girlfriend on the panel, ever so lovely and sophisticated in her super-wide navy bellbottoms.

I saw him again at a planning meeting at Bill Miller’s house in the Claremont district during the citywide 1969 uprising in protest of the university’s fencing of a plot of land citizens had crafted into a people’s park. Just a handful of us came to the meeting, and Tom reported that he had learned from his Deep Throat within the Berkeley Police Department that a mass bust was in the works. I was spellbound sitting just a breath away from him, listening, taking his presence in. Indeed, I got arrested at the bust along with some 400 others in May of 1969, was carted off to Santa Rita Detention Center in a windowless prison bus, was corralled into a claustrophobia-producing solitary cell with a bevy of some fifty terrified, exceptionally loud, and disorganized women, and in the end was saved from more lengthy prison time by left-wing pro bono lawyer Bob Treuhaft.

Then in June, the month after the People’s Park uprising, there was a new demo on the Berkeley campus. That was the moment I realized that we long-timers in the streets had unwittingly, by all appearances through tacit psychic connection, developed a group method in which we would come together, burst apart, come together, then burst apart again depending on if the police were on the attack or not. But this new crop of protesters … well, they were proving to be an insipid shade of naïve green. As summer vacation was upon us, they had arrived in our skillful midst from all directions to have their “Berkeley Experience,” and they knew exactly jack shit about how to maneuver as a unified mass. Tom was there under the Sproul arch doing his best to direct this herd of cats—with no success at all.

As you can plainly see, I didn’t have a lot of quality contact with the object of my adoration in Berkeley. Stay tuned, though: decades later he would change the course of my life. By 2005 he was married to a spirited Canadian actress named Barbara Williams. He’d survived a heart attack and was ever so aware of the fleeting nature of life. He had traveled to New Mexico for a Christmas reunion with his family from the days when he was married to Jane Fonda. We were crossing the parking lot of the Santuario de Chimayó, and I made my confession. We both had a good laugh.

Is Tom most notorious for his role in starting Students for a Democratic Society in 1961? Or for his civil-rights activism in the South and in Newark? Or for being the theoretician of the Chicago 8 along with Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Bobby Seale, David Dellinger, Rennie Davis, Lee Weiner, and John Froines? Is he most known for his work as a progressive California State Assemblyman and Senator? Or for his twenty-plus books? Is he most recognized for the ground-breaking work he did with street gangs in Los Angeles? Or perhaps for marrying Jane Fonda? The answer could depend on your politics: some may think his (by 1979) 22,000-page, three-foot-high FBI file is the definition of immortality. Whatever the answer, it is clear that Tom was born to give of himself wholly.

He was, in fact, born in 1939 in Royal Oak, Michigan to Genevieve and John Hayden, both of Irish descent. After graduating from Dondero High School, he went on to the University of Michigan, where he was editor of the Michigan Daily. At the time, the National Student Association still held sway with its Cold-War, anti-communist politics. Tom joined with others to found the Students for a Democratic Society, and he was its president in 1962 and ‘63. During this time, he also traveled through the South as a Freedom Rider to desegregate public areas like train stations, and he was the central drafter of SDS’s Port Huron Statement. Its first sentence opened the door to the students and intellectuals who were to burst upon U.S. consciousness: “We are people of this generation, bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably at the world we inherit.” Indeed, its ambition was to kick-start “a radically new democratic political movement,” one based in participatory rather than representative decision-making. The essay quickly became a founding document of both the emerging student movements and the New Left.

Tom musing at his FBI file in 1979. (Imagine its size by 2015!) First appearance in the Los Angeles Times in 1979; later in “The Hunters and the Hunted” by Seth Rosenfeld, New York Times, October 5, 2012.

Quite early in the appearance of skepticism regarding United States involvement in Vietnam, in 1965 Tom, Quaker peace activist Staughton Lynd, and Communist Party U.S.A. leader Herbert Aptheker traveled to North Vietnam and Hanoi. The buildup to the U.S.’s eventual full-out participation—at that point mainly via “advisors”—was only just becoming evident, and it was a daring maneuver for citizens, on their own, to not accept what the newspapers reported, but to actually check up on their government’s deeds. The trip laid the basis of a primary theme in Tom’s life. In 1968 he was one of the main organizers of the anti-war protests outside the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, and six months later the Chicago 8 were indicted on federal charges of conspiracy to inflame violence. Tom was convicted of crossing state lines to incite a riot, but the charges were reversed upon appeal. He went on to found the Indochina Peace Campaign that, from 1972 until the U.S. pull-out in 1975, organized protests, and demanded unconditional amnesty for draft dodgers.

I was on a speaking tour in the mid-’90s. Needless to say, I was more than thrilled when Tom and Barbara showed up at my talk on ecopsychology in Los Angeles. My routine was to choose a musician from the community who could improvise an on-the-spot “sound track” for the lecture; I would turn to this person at intervals, and the given task was for her/him to bounce off of my stories using musical expression. The approach had been a wild success at the Prescott College ecopsych gathering in Arizona the year before, where a passionate young singer who sang throughout my presentation brought the house down and we shared a raucous standing ovation. In this case I was directed to a tall Swedish man whose only melodious talent, it turned out too late, was to bang on a chair seat. Afterward, Tom pulled me aside to advise that the talk was great—but the musician … well … “he had to go.”

I agreed heartily, and our post-crush friendship was off to a comical start. What followed was a tour of L.A. with the Williams-Hayden duo, including lunch on the Santa Monica boardwalk amid bathing suits and roller skaters, a peek at the ‘hood of his gang friends, an unexpected car breakdown—and superb conversation. What I encountered was a man more multifaceted than I could have imagined or appreciated in the ‘60s. One might posit that a political animal doesn’t need to be or doesn’t have time to be reflective—Dan Quail being the best example of what level of intelligence it takes to be successful in Realpolitik; Adlai Stevenson an example of what can happen if one is too much the “egghead.” But Tom was swirling with questions and insights, and he wanted to know what I thought. What about this new phenomenon of multiculturalism? What would happen to U.S. society if it truly took hold? How would established religion need to change if it were to embrace ecology? How might one talk to religious leaders to make that happen?

Several years after our time together in Los Angeles, upon flying into the airport in Albuquerque he called to see if he might visit me. And so it was: on the afternoon of Christmas Eve, 2005, Tom drove from Jane Fonda’s ranch south of Santa Fe north to Chimayó. We sat for a spell in the Santuario and ate lunch at Rancho de Chimayó, where sopapillas con miel reign supreme. My jaw just about spilled the half-chewed delight when he invited me to come to Bolivia—in four weeks. I resisted. It sounded like a preposterous thing to do: the trip was too soon, Bolivia was too far away, it would be too expensive. But Tom gazed at me through those saltand-pepper eyes. “You have to come. After all the dictatorships, they have elected their first indigenous president, a campesino named Evo Morales,” he insisted, and then revealing his ever-present awareness that we would not last forever: “Such a thing will never happen again in our lifetimes.”

He was right. Bolivia was literally dancing upon its boulevards and dirt paths, people were either crying or singing for joy on street corners, in buses and cafés everyone was feverishly talking politics. Tom stayed for four days to gather information for an article in The Nation and then launched off to do interviews in Venezuela, to be followed by his annual jaunt to the L.A. Dodgers fantasy baseball camp in Arizona.

I, on the other hand, was so taken by the spirit of the Bolivian people that I returned—and stayed for the rest of my life.

At a certain point a wrinkle in Tom’s and my differing political styles surfaced. Political focus, I believe, is shaped by the Zeitgeist into which we are born, the particular injustice in our midst, and the education that we receive. The wrinkles and labyrinths of our personalities also contribute a great deal to the themes and means of our politics as well—and appear to explain the different paths Tom and I followed.

Tom is the kind of visionary who enacts his ideals for making a better world through concrete acts in society as it exists right now. In the 1970s he and Jane Fonda organized the Campaign for Economic Democracy that, in cahoots with California Governor Jerry Brown, promoted such issues as renters rights and solar energy, and whose most astounding claim to fame was participating in the closure of the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant in San Luis Obispo, California, via referendum. Despite serving the state legislature under Republican governors for sixteen of his eighteen years in office (twice surviving expulsion hearings propelled by conservatives), he managed to get over 100 progressive measures passed—including achieving equal access to state universities for the disabled, funding for tutors in after-school programs, monies to restore Native sacred springs, requirements for trigger locks on guns, funding for gang-intervention programs, and the largest state park and environmental restoration bond in U.S. history. He also ran as the Democratic candidate for mayor as well as for U.S. Senate.

I cheer such accomplishments, but I am made from a different mold: my work stems from a systemic view of the dysfunction of civilization as a whole and, against the constant onslaught, seeks to preserve the archetypal in the human experience, so rapidly being shredded in this age of capitalist techno-globalization. Too, my sensibility leans more toward the hyper-creative, anarchistic, pre-institutional phase of a social movement; writing/passing legislation and negotiating with government have never been my fortes.

Despite Tom’s unsuccessful attempts to convince me that I should join him in a campaign to legalize Bolivia’s coca plant for medical use in the U.S., he displayed the wisdom of his long experience in politics: he didn’t let disappointment get in the way of our connection. I watched him move like Baryshnikov past the chasm widening between us—and I, with so much more maturity than the flailing tentacles of a mad crush, truly loved him for it.

And the man just kept keepin’ on with his commitment. In 2015, at the height of Bernie Sanders’ campaign for the Democratic nomination for president, he penned a controversial essay for progressives revealing his support of Hillary Clinton—with hopes that Sanders’ effort would swing her to the left. That same year he suffered a mild stroke, but nonetheless showed up at the 2016 Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia as a delegate in support of Clinton’s nomination. The Convention was his undoing. He came home to Los Angeles a very ill man.

The morning of October 24th I sleepily padded down to my office in Sucre, Bolivia and opened my email. There I found four red-flagged messages shrieking urgency—from Native American activist Suzan Harjo in D.C., administrator/ecologist Marc Kasky in San Francisco, editor/musician Whitney Smith in Toronto, and non-profit director Lee Cridland in Cochabamba—each passing along a link to an article posted on one media venue or another. Tom had died. Shock gripped my bones, just as the eulogies and accolades poured in. My Goddess! They came from Huffington Post, New York Times, Scotland Herald, Organized Rage, Aljazeera, The Guardian, Cuba Net, and on. Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti wrote, “Tom Hayden fought harder for what he believed than just about anyone I have known.” Writer/Columbia University professor Trey Ellis said, “As a lifelong believer in the collective, he didn’t take credit. He shared. He dedicated his life to good cause after good cause, relentlessly seeking out justice wherever it was lacking.”

How lucky we had all been to count him one of our own—and how we, and our movements for justice, miss him.