Читать книгу In the Company of Rebels - Chellis Glendinning - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеV. “I’D LIKE TO SAY A FEW WORDS ABOUT THE ENVIRONMENT. AFTER ALL, WHERE WOULD WE BE WITHOUT IT?”

ECOLOGY IN SAN FRANCISCO

If you don’t like the news, go out and make some of your own!

—WES “SCOOP” NISKER, “THE LAST NEWS SHOW,” KSAN-FM

BY THE 1970S THE San Francisco Bay Area had given New York City a run for its money as the political, cultural, and consciousness Place to Be. Surrounded by ocean and bay, covered in Eucalyptus and Manzanita, burgeoning with tropical and temperate plant life, and just down the foothills from Yosemite National Park and the Sierra Nevada mountains—it was natural that, among the other flowerings going on, the ecology movement would find its most avid escorts in the urban areas cupping both inlet and sea.

The ghosts of John Muir and Ishi haunted the woods of Mount Tamalpais, after all. David Brower was a Berkeley man, lighting a fire under what essentially had been a hiking organization to become the forceful environmental fighting Sierra Club. Under his leadership as president, the San Francisco chapter of the club came to boast one of the national organization’s largest and most active memberships. Also, under his guidance, Friends of the Earth, the League of Conservation Voters, and Earth Island Institute were birthed into existence. Meanwhile, architect Zach Stewart launched the River Terminus Expeditions up the Sacramento River so that wannabe and veritable activists could learn firsthand about the watershed of the northern California bioregion, while Marc Kasky took on the then-hippie Ecology Center in North Beach and turned it into a vital hub of environmental awareness and organic muffins.

In 1969 the September issue of Ramparts had put out its startling “The Death of the Oceans” essay, by conservation biologist Paul Ehrlich, predicting their demise via pollution and acidification by the year 1979. And there were all those colorful back-to-the-landers with their teepees, Mendocino County communes, organic gardens, compost piles, and Chief Seattle posters …

MARC KASKY: THE MADCAP ECOLOGIST

(1944–)

I’d like to say a few words about the environment.

After all, where would we be without it?

—M.K., IMPROVISATIONAL SKIT PERFORMED AT HOTEL WAWONA, YOSEMITE. HALLOWEEN 1984.

The first year I lived in North Beach with my lover Marc Kasky, he packed up his tent and enough dried food for ten days, and he launched off in his size-thirteen hiking boots to what became a yearly solo hike through the Sierras. That first year, too, he was visited by a hairy spirit in the night. The thing looked like a sort of werewolf-yeti. It appeared at the foot of his sleeping bag, as such creatures have a tendency to do, and crooking its claw in the shape of Little Bo Peep’s cane, beckoned Marc to come. It was the dead of night, and the forest was pitch-black. Marc graciously declined, rolled over, and went back to sleep.

I’m not sure if these kinds of visitations were not normal fare for the man. He had, after all, lived a life of wild and hairy ideas. In fact, he had an idea for just about every challenge that lay before him. Consider the public TV station he instigated at Franconia College in answer to the school’s need to bridge the gap between the insulated student body and the town’s working-class community: the communications students made programs about the town and, boasting next-to-nothing funds for a full-time station, set up a camera in the snowy woods through the night when there were no other shows to be had. Or the basketball team he started. Franconia possessed no phys. ed. department, no basketballs, no gymnasium, no outfits, no lanky athletic stars—and so, at the very least, the project was a risk. But it was an ingenious scheme as the town might then get behind its team.

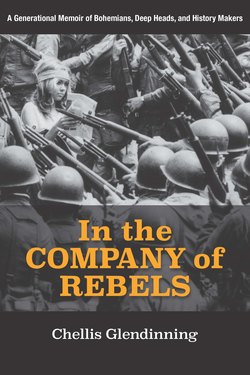

What would happen if everything just … stopped? Positively Fourth Street mural at Fort Mason Center, San Francisco, 1976. Artists: John Wehrle and John Rampley. Photo credit: Jim Petrillo. Courtesy of John Wehrle.

One problem to be hurdled was that the White Mountains of Vermont presented a snow barrier to the other teams that would have to travel north, so they decided to only play, as the saying goes, “away from home.” Upon the team’s first such bus ride to Hampshire College in Massachusetts, an aghast Marc realized they didn’t have a handle. Since basketball courts have a score board that pits “Home” against “Visitors,” Marc thought, they could be the Visitors. They actually won that first game—and the national media went feral. Sports Illustrated, the New York Times, plus newspapers across the country published stories about the Franconia Visitors, and BINGO! the town—now with its very own TV station and an undefeated basketball team—began to feel very good about its college.

Yes, wild spirits sprouted from the head of Marc Kasky. As a student coordinator of Eugene McCarthy’s run for President in 1968, his idea for gaining votes in the all-important New Hampshire primary was not to chuck the campaign’s anti-war message down the throats of the voters of Berlin. It was to set up democracy centers where citizens could experience that they were responsible enough, intelligent enough, free enough to debate the issues and come to their own conclusions. The McCarthys were so impressed with this unique approach that they asked Marc to do the same in Grand Island, Nebraska; Eugene, Oregon; and Santa Monica, California. On the night of the primary they invited him to watch the results in their hotel room, and in her memoir Private Faces, Public Places, Abigail McCarthy called Marc “a symbol of all that was good in the student involvement in the campaign, all that was good in the new politics, all that was good in the campaign itself.”

Later, in the ‘70s, when he was director of San Francisco’s Ecology Center, Marc provided grounding for the churn and swirl of emerging environmental consciousness. The center was on lower Columbus Avenue, below Grant Street, known for its rebel dynamism since the Beat days, and right across from the very symbol of the economic forces that were wreaking corporate havoc upon the Earth: the new pyramid-shaped Transamerica Building.

First thing: in hopes of attracting a few bankers and financial advisors, Marc tore down the burlap wall coverings that hinted at hippiedom and painted the place crisp white. Then he and the staff set up an all-you-can-eat vegetarian restaurant, an eco art gallery, and lunchtime discussions on the city and its quality of life. Sure enough, people from the Financial District poured in. Secretaries. Brokers. Newspaper vendors. Radio commentator Wes “Scoop” Nisker (of “If You Don’t Like the News, Go Out and Make Some of Your Own” repute) popped by for coffee. Ponderosa Pine, who for years had trod the sidewalks of San Francisco without shoes, lent his rants on the glories to be had if only the nation could be broken down into self-sustaining bioregions. Stephanie Mills was a regular; she had gained clout when in 1969 she delivered her Mills College valedictorian lecture on the decision not to bear children due to overpopulation. Sierra Club president David Brower made the occasional appearance. And lo and behold for the power of painted white walls, former New York advertising executive Jerry Mander came to discuss his infamous Save the Whales ad campaign.

Architect Zack Stewart’s Canessa Gallery sat across the street on Montgomery. Ever the bearded eccentric, Zack enlisted the curious and courageous to join him on a boat trip up the Sacramento River so that the budding environmentalists could get to know what the Bay Area landscape looks like, where the city’s water comes from, who is polluting the river, etc.: in essence, to develop a Sense of Place. His River Terminus Expeditions shaped up to be a marine version of the Merry Pranksters’ hippie bus. It boasted three houseboats sleeping ten people each for three days. Each boat had a captain and a navigator, but Marc … well … he was dubbed Admiral of the whole shebang.

Accompanied by Ecology Center herbal teas and fresh-baked, whole-grain muffins, the All-Species Parade through the streets of the city was launched in 1977. The Rain Dance at the Legion of Honor was spawned to wake up the deities and counter the unforgiving 1976 drought; the ceremony was held on a Friday night, and by Saturday morning (of all rarities in San Francisco), it snowed. A block up Columbus, the International Hotel was throwing otherwise homeless, elderly residents into the streets; protest erupted, and the Ecology Center provided childcare for picketers. Then, like some kind of preordained synchronicity, San Francisco’s first environmental campaign focused on that concrete behemoth of a building across Columbus with its energy-sucking air conditioners, and its windows that couldn’t be opened to let in the Bay’s fresh, cool air.

Marc Kasky above Fort Mason Center, 1982. Photo credit: now-defunct San Francisco Food Coop. Courtesy of Marc Kasky.

And since the “straight” drop-ins and non–ecologically minded were confused as to how to live lightly on the land, Marc came up with his how-to-solve-daily-problems-as-if-the-planet-mattered radio show on KPFA-FM called “M.I.N.T.” Money Is Not Thrilling. One caller would confess the eco-disastrous temptation to buy a new car, and by the seat of his pants, Marc would advise him to paint the old one, get some new upholstery, add a hood ornament. Another would moan about her gripping desire to own a Kirby vacuum cleaner like the one her neighbor had; Marc would propose sharing machines.

Imagine how life was for me: I lived for seven and a half years with this fount of ingenuity. When I met Marc in 1979, he was director for Fort Mason Center, a World War II army base perched on the edge of the San Francisco Bay, and for 24 years he guided its development from an army base into a people’s cultural center. There were non-profit headquarters for the likes of Media Alliance, Magic Theater, and Blue Bear Music School. There were classrooms and museums and performance venues. The Zen Center’s Greens restaurant whipped up meals of organic vegetables grown on their Green Gulch ranch in Marin County and, needless to say, served their own baked Tassajara bread. Marc oversaw the building of the 450-seat Cowell Theater; the relocation/restoration of the in-decline eco mural “Positively 4th Street” depicting the reclamation of a defunct freeway off-ramp by plants and animals; and the renovation of the last World War II Liberty Ship, the Jeremiah O’Brian.

When work was finished, the ideas didn’t stop. Steeped in the psychological wing of the anti-nuclear movement of the 1980s, I was running an organization called Waking Up in the Nuclear Age. The motivation of WUINA’s cadre of mental health professionals was to present lectures on the psychological ramifications of living with the arms race and workshops to help citizens break through the denial and, as psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton called it, psychic numbing behind the paralysis of the population since the atomic era had begun. We were faced with a U.S. president taunting the opposition with inflammatory phrases like “Evil Empire” and bragging of bold, new weapons systems like Star Wars and Cruise Missiles; the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists’ Doomsday Clock had been readjusted from its former seven minutes before midnight in 1980 to a hair-trigger three by 1984. Our task was to catalyze a new generation of activists who would plunge into the movement against nuclear proliferation.

After the workshop goers’ fear and grief had been excavated and expressed, we would meditate to envision ways to contribute to making a safer world. As far back as 1977, Marc had come up with the Vivatron Bomb, an antidote to the neutron bomb touted by the U.S. government as a military techno-strategy that, upon detonation, would kill all living beings but leave buildings, roads, bridges, vehicles, and airports intact. Marc’s notion was to create a bomb that would destroy the buildings, roads, bridges, vehicles, and airports that ecologists were identifying as sources of a lifestyle that was devastating the planet—and leave the people, animals, and plants to thrive anew.

The ways he and I together contributed to making a safer world were to organize protests, march against nearby weapons-researching Livermore Laboratory, canvas door-to-door for the Nuclear Freeze, write articles, and do radio interviews. To lend some humor to the effort, we also decided to host a contest toward a citizens’ invention of the Vivatron Bomb. Parade, California Living, Albuquerque Journal, and San Francisco Bay Guardian ran notices for the competition, and letters poured in from all over the United States—five shopping bags of entries stuffed to the brim, to be exact. On the drive to Bolinas where, in a borrowed cottage, we were to read the ideas and determine the winner, I was suddenly struck with the fact that we did not actually have the $50,000 prize money we had so frivolously promised. But Marc, of course, had thought all that through: the contest rules stated that the entries had to be not only great ideas for inventions, but also had to have been demonstrated in a major U.S. city. Needless to say, no Vivatron Bomb had yet toppled the Sears Building or set ablaze the New York Thruway—and so we published an article in California Living presenting the best of the lot.

This wellspring of ideas was third-generation Russian immigrant: the family surname before hitting Ellis Island had been Kasajovic, which translated to “fur pelt”; his great-grandfather had been a hat maker. The authorities immediately changed it to Kaskowitz; then when, as a Jew, Marc’s father set out to play professional baseball, to avoid discrimination he changed it to Kasky. One of Marc’s foremost beloveds was the woman who had braved the journey across the Atlantic from Eastern Europe and raised four children alone: Grandmother Rae. From her he learned independence of mind.

His parents were Alice and Dick Kasky. They set about making their home in Stamford, Connecticut, where, upon reaching only the minor leagues, Dick opened a tire store. Marc launched a brief career as what in those days was called a JD (juvenile delinquent)—robbing cars, breaking/entering. Then, suddenly, he made a 180-degree turn-around and became the first in the family to go to college: Connecticut Wesleyan, and later, to Yale for a master’s in urban planning. But the times lent themselves more to “drop out/tune in” work than to joining a firm in Hartford. Marc got a job as a community organizer in Jersey City.

His apartment was a third floor walk-up. The Hippie Revolution was in full bloom, although admittedly not that evident in working-class Jersey City, and on his paltry organizer’s salary, he had zero cash to spend on fixing up the place. So he gathered a bunch of wooden fruit crates and some enormous slabs of foam rubber, painted them neon orange, and set them in a sort of amphitheater arrangement in the otherwise bare living room.

Imagine Grandmother Rae’s visit. Here she had trudged hundreds of miles behind a donkey cart in the dead of winter, braved a harrowing trip across the ocean on a crammed steamer replete with fleas, lice, and the vomit of the seasick, and made her heroic way into a New York City burgeoning with immigrants like herself looking for the same bottom-level jobs. Now at last, here was the fruit of her efforts, her grandson who had, by the might of his own intelligence, achieved the American Dream: he had gone to Yale and graduated with a master’s degree! The door swung open. Inside: a sweltering walk-up apartment boasting termite-gnawed window sills, chipped linoleum floor—and a (Sears and Roebuck, not!) living room set of used cartons and screeching orange foam pads!

Marc’s work made an ingenious pivot in the 1990s. A proponent of Richard Grossman’s work on the legal “personhood” that bestows the freedoms (read: unimpeded license) corporations use to exploit workers and resources, he and his long-time buddy attorney Alan Caplan cooked up a means to stymie offenders. They launched a series of lawsuits: Kasky vs. Jolly Green Giant, Kasky vs. Perrier, and the most infamous, Kasky vs. Nike Corporation. The key to each was false advertising. Jolly Green Giant had advertised that its recipe for frozen vegetable dinners was “California style”—yet the product was actually made in Mexico. Perrier had boasted that its water was naturally carbonated underground and bottled at the source—when in fact the spring had dried up years before and the water came out of a tap. Marc and Alan won both cases.

Not once did they request personal remuneration in the settlements. Never short on ideas, Marc requested that Jolly Green Giant donate the money to Second Harvest, a non-profit that distributed to food banks. The Perrier settlement occurred during the riots in Los Angeles, and he proposed—and got—Perrier to supply thousands of water bottles to protestors and looters in the streets!

The Nike case, though—this one thrust him into the limelight of the national financial world, including a five-page feature in Fortune called “Nike Code of Conduct,” plus stories in the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, San Francisco Chronicle, etc. The gist of the suit was that Nike publicized that its workers in Indonesia and Vietnam labored in safe conditions. In reality, according to a report by its own team leaked by a disgruntled worker to the New York Times, abuses abounded. Caplan’s law firm Bushnell, Caplan and Fielding proved to be too small for the case, and Milberg Weiss of Los Angeles joined up. It went to municipal court, then to appeals court, both of which they lost. In these suits Marc was, of all things, listed as “Private Attorney General” of the State of California so that he could not personally benefit from any gains (a title he regarded as a step down from Admiral of the house boats). His team of lawyers appealed to the State Supreme Court and won. Nike appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Amazingly, the decision of Kasky vs. Nike went for the plaintiff—and, as a result, millions of dollars went to groups monitoring sweatshop practices around the world. The anti-corporate-globalization movement, of course, was thrilled. Corporations: 0, Visitors: 3.

Marc and I broke up in 1987. A few years later, after much deliberation on the pros and cons of the legal institution of marriage, he and his new love, actress Cat Carr, tied the knot to a full house at the Cowell Theater—with all his former lovers there to give him away. When I visited the Bay Area from my then-home in New Mexico, they always invited me to stay at their house. Marc continues his work to challenge corporate personhood, and each summer he and Cat drive their 1974 Chrysler Commander to the Burning Man celebration in Black Rock, Nevada. There the intrepid Admiral/Attorney General sits—dressed in a blue fake-fur jacket and billowing orange dance pants, eager to share the wisdom of experience with young people at a booth he calls Counsel from an Elder.

Another wild idea …

PONDEROSA PINE: SIDEWALK SOLES

(1932–2014)

That’s not a new idea, bro. We knew THAAAA-AAAT like, you know, for-EV-er!

—P.P., EARTH READ OUT

Ponderosa Pine was known for the soles of his feet; they had not seen the insides of a pair of shoes since 1968. That year an ecological epiphany struck him as he departed all trappings of the straight life in which his name had been Keith Lampe and morphed into an eco pilgrim named for a tree. Ever since then he had tread the sidewalks of the Haight, the stone paths of Golden Gate Park, and the beaches of Bolinas with neither hide, hair, nor last of footwear.

I got a glimpse of those soles when, fifteen years later, Marc Kasky introduced me to him at Fort Mason Center. They were thick. They were hard. They were the color of the black hole of the universe. Dear reader, we are talking an inch of freshly tarred epidermis contoured by daily deployment to resemble a Vibram sole.

Ponderosa’s feet reflected his dedication to the cause. At the other end of his ever-so-lean-from-walking body (he refused to mix his dignity with that of carbon-emitting machines, regularly walking the thirty miles from his home in Bolinas to San Francisco), his mind was devoting its considerable assets to the miserable state of the planet. In her book Whatever Happened to Ecology? Stephanie Mills calls him the “grand-daddy of all the bare-knuckles critics of environmentalism,” clearly a 1980s moniker from when climate change, ozone depletion, rising seas, dying species, contaminated cities, and ruined ecosystems were not as evident as they are today and even the left-wing intellectuals at The Nation thought ecology a bogus concern. Stephanie also calls Ponderosa “a barefoot mendicant chanter and general thorn in the side of people of lesser mettle … a guy destined to make us all deeply uncomfortable in our insufficiency of action.”

This soleless/soulful pioneer lived so intensely in the Here-and-Now that he seemed a man without a past. But in the world of material existence and calculated linear time, Keith Lampe was born in 1932 to Harriet and William Lampe in Wayne, Pennsylvania, the eldest of three siblings, and he grew up during the Depression. In his early career, he was both an officer in the U.S. Army during the Korean War and a Paris-based reporter for Randolph Hearst’s right-wing International News Service. Upon hearing about the murders of three civil rights workers in 1964 in Mississippi, though, he chucked his formally sanctioned career, headed back to the States, and got himself hired by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee as press agent. Then, in 1966, just as the Vietnam War was being launched, he burned his discharge papers and medals on national TV and awoke from his previous life to find himself on stage in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, shoeless with his unkempt beard waving in the ocean wind, speaking to throngs of stoned hippies about cosmic consciousness, leading group meditations, and performing improvisational music with drums, lutes, synthesizer, and belly-dancing women.

Pine around 1970 at Marx Meadow in Golden Gate Park. Photo credit and courtesy of James Stark.

The All Species phenomenon took off! Ceremonialist Chris Wells jumped in and took the event all over the U.S., to Mexico and Sweden. Here, a gathering dedicated to Turtle Island, the name given to North America by many Native peoples. Earth Day 1992, Kansas City, Missouri. Photo credit: Ed Kendrick. Courtesy of Marty Kraft and All Species Project.

Ponderosa was among the first to articulate the importance of an extremely radical philosophy and politics called bioregionalism. In his weekly mimeographed publication Earth Read Out he spouted its underlying wisdom: for two million years we humans lived in ecological terrains defined by the extent of local watershed and cohesion of flora and fauna, developing cultures as reflections of the natural world around/within us. Take, for instance, the obvious differences between traditional Inuit lifeways and those of the Plains Indians, between the world of Pacific Islanders and that of the Aymara in the altiplano. The unfortunate lunge toward expansive survival tactics that has led to imperialism and finally to economic globalization also created what became the archetypal battle between warring, technological nation-states and in-place, nature-based cultures. According to Ponderosa, if we are to survive, it is to this latter state of existence that we must return. Bioregionalism stands among the various options for breaking down empires and resuscitating archetypal human existence.

As one manifestation of making such a homecoming, Ponderosa—along with his wife Olive Tree—invented the All-Species Day Parade as a dynamic way to build community and consciousness. The first took place in 1978 in San Francisco. Stephanie Mills showed up as a Monarch butterfly. Marc Kasky was there too, dressed as his animal totem, the otter. The eco group Friends of the River arrived with some twenty members dressed as the Tuolumne and Stanislaus Rivers. Fantastic! Scoop Nisker appeared as a primate ancestor, bioregionalists Peter Berg and Judy Goldhaft as forest creatures. Ponderosa came covered in tree bark, twigs, and brush chaotically twisting this way and that.

Another manifestation of Ponderosa’s dedication to a return to safe, satisfying, and sustainable living was his stellar political action record:

* In 1965, as a former Army officer during the Korean War, co-founded Veterans and Reservists to End the War in Vietnam;

* 1966, along with other veterans, set fire to discharge papers, service medals, and campaign ribbons on national TV;

* 1966, New York City: protest against Dow Chemical for what he called the company’s “obscene manufacture of napalm”;

* 1967, Army Induction Center, New York City: during Stop the Draft Week protests, two separate arrests;

* 1968, Hudson River, New York City: civil disobedience to delay the departure of a Navy destroyer to Vietnam;

* 1968, Senate Gallery, Washington, D.C.: arrested for dumping anti-war leaflets on elected officials from balcony above;

* 1968, Pentagon March, Washington, D.C.: arrested with Jerry Rubin, Noam Chomsky, Norman Mailer, Abbie Hoffman, and Stew Albert;

* 1987, World Bank headquarters, New York City: demonstration against funding for a superhighway slated to pass through the endangered Amazon rainforest;

* 2000, White House Rotunda, Washington, D.C.: protest in favor of campaign finance reform—along with climate change activist Bill McKibben, political activist Granny D, etc.

Needless to say, Ponderosa traveled to Chicago in 1968 to protest the Democratic Party Convention that had given the cold shoulder to the popular anti-war candidate Eugene McCarthy in favor of Old Party machine cog Hubert Humphrey. Here, amid fervent protestors and rampaging police forces, Ponderosa learned that New York City’s finest had compiled a dossier detailing his activities on the East Coast and had sent it to their Chicago colleagues. In its forty pages Ponderosa was described as “an especially dangerous leader.” The report argued that he advised activists to disobey laws, while he—in typical hippie/yippie fashion—claimed that he had only encouraged people to “Do Your Own Thing.”

In 1968 Keith, wife Judy, and daughter Issa made the cross-continental move to Berkeley. Here, perhaps more than ever, amid the glories of the blooming counter culture, he morphed into the activist who would walk the streets barefoot, rename himself “Ponderosa Pine” and—with growing ecological awareness—position his body between “a truck carrying redwood corpses from a nearby tree-slaughter site” and eternity. As humorist Paul Krasner describes the transition: “Hippies became freaks. Negros became blacks. Girls became women. Richard Alpert became Baba Ram Das. High Romney became Wavy Gravy, and his wife became Jahanarah. Yippie organizer Keith Lampe became Ponderosa Pine, and his girlfriend became Olive Tree.”

Insisting always on the purity of ideas and actions, Ponderosa fell into the occasional but regular bout of self-righteousness. Or as Stephanie Mills defined that particular stance, making others feel “deeply uncomfortable in their insufficiency of action.” To boot, his tone in pointing out said insufficiency was “cranky” and “cantankerous.” That’s the way Charlene Spretnak put it when she waded into a controversy with “Mr. Pine” that did nothing but let loose said qualities. In May of 1987 she wrote him a letter attempting to inculcate compassion after he had publicly trashed environmentalist David Brower and historian/bioregionalist Kirkpatrick Sale. His complaint was that they (and now Charlene) were mere armchair ecologists/regionalists—“slapstick satirists”—hiding behind foundation grants and typewriters rather than placing their bodies in front of trucks hauling the freshly murdered carcasses of our brothers and sisters, the trees.

Ponderosa published Charlene’s correspondence in his newsletter Deep Bioregional Action-Examiner and offered up a cranky, cantankerous epistle in response. It included such declarations as “You behave as though you think I suggested that David slaughter an indeterminate number of trees to occupy my postal box with junk mail playing on people’s fears to suck maximal money from them.” In answer to Charlene’s contention that his personal put-downs of fellow activists were violent tactics, he wrote: “The violence of your tactics is that you’ve left a long trail of blood behind you by bringing out one two three four! books already …” Respected feminist Charlene Spretnak had just come out with Green Politics: The Global Promise (1984), co-written with physicist Fritjof Capra, the first book about the progressive, neither-left-nor-right Green Party of Germany. He continued his tirade, “I’ve heard the wide-awake screams of our sisters as the saw rips through their ankles and they tumble to oblivion, Charlene, and I can assure you that you’re leading a very violent life.”

Plus, the kicker: “I’m grateful to have a copy of that cute photo of us taken at that party in Berkeley. The particular ‘party-dress’ you’re wearing makes you look the demure, ingenuous girl-next-door who has just returned from her junior-year-abroad with a rather good term paper all about environmental politics in Germany.”

Nearing retirement in the late 1980s, Ponderosa moved to Chiang Mai, Thailand, where the tropical climate suited him better than that of Bolinas’ Pacific coastline and dollars from his Social Security pension went farther towards survival than they would have inside the U.S. I hear tell that his journey to Asia and subsequent return visits heralded the first time since 1968 that he had actually donned a pair of shoes. As the twenty-first century unfolded—particularly after the 2001 Twin Towers attacks and the ensuing Shoe Bomber incident—shoelessness would make passing through airport control faster, but the airlines displayed zero tolerance for the likes of he who now had been reborn and was calling himself Ro-Non-So-Ye. Ro-Non responded to regulations by donning a pair of flip-flops for these transcontinental flights and used the same technique right through his subsequent and final move to the mountains of southern Ecuador.

Here he established the “Double Helix Office in the Global South White House” and relaunched the environmental reporting he had begun so many years before. The former Earth Read Out and Deep Bioregional Action-Examiner were remade as A Day in the Life; its daily accounts—often megabyte-sized, on topics as far afield as the Ebola epidemic, human rights violations, non-ecological education, and climate engineering—were penned, as always, in his emblematic cranky-cantankerous-comedic-flamboyant rant style. Combining the panoramic vista of an informed elder with his bent toward transcendental music and cosmic consciousness, Ro-Non also became something of an eco guru to the extranjero community in Ecuador.

But he was not well. Ever since the 1970s when popular thanologist Dr. Elizabeth Kubler-Ross challenged the social taboo against conscious, visible death and dying, we have come to understand that communication about impending death makes its inevitable arrival not any less agonizing or unfathomable—but still somehow easier to bear. Ro-Non gave a great gift to all the folks who loved him when he penned and posted this epistle, sober and yet ever characteristic of the man’s originality:

October 31, 2014

Dear Friends and Colleagues,

… I’ve been severely ill for more than four weeks now. Especially difficult have been frequent episodes of convulsive/spasmodic coughing shaking the inside of my body quite painfully.

My main problem has been my lungs, which constantly fill with phlegm and when added to severe emphysema and asthma cause quite a problem.

I’ve had two mainstream doctors up here to my mountain retreat but they’ve been unable to improve my condition.

So Tuesday I asked for a visit from a local shaman whom I’ve known for a few years now and for whom I have great respect. What he said is quite interesting. Here’s one of his most memorable lines: “Too much compassion for plants and animals causes a lung problem.” …

So what I think we should take from this is that a much higher percentage of our current illnesses than we think are psychosomatic (or neurosomatic) rather than simply somatic. For example, we may think we’re sick from toxic chemtrail residues when actually we’re sick from these plus the neural stress resulting from having to absorb the info that those controlling us are so evil that they perpetrate chemtrails.

Certainly the news of these past four weeks has been more horrendous than that of any similar period I can remember. One of my most aware readers commented a few days ago that “Hell has come to earth.”

I’ve had information sickness several times before but always mildly: two or three days of deep fatigue, then back to okay again. In any case, yesterday morning my housemate came up to my second-floor room just as I was waking and said: “I’m scared. I think you are dying.” That same thought had occurred to me just the day before as I wondered how I was going to make it through this at 83….

On the positive side, it’s certainly a respectable cause of death: Natural World Hyperconcern (NWH).

And I’ve already arranged for my death to instigate at least one more really good party. Forty-nine days following it, there’ll be a Bardo Party for me at the Bolinas Community Center with excellent live music and potluck food. Yeah, at least my death will have some value….

Power to the Flora,

Keith Lampe, Ro-Non-So-Te, Ponderosa Pine ~ Volunteer

P.S. NYC graffiti a few decades ago: Death Is Nature’s Way of Telling You to Slow Down.