Читать книгу In the Company of Rebels - Chellis Glendinning - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеVI. THE ROARING INSIDE HER: FEMINISM

A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle.

—FEMINIST AXIOM COINED BY IRINA DUNN, 1970

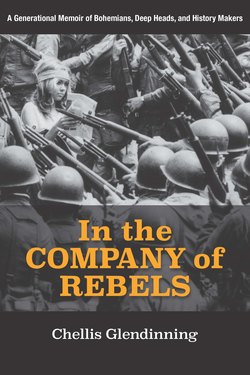

Women’s Strike for Equality, New York City, August 26, 1970. Photo credit: ©Diana Davies. Courtesy of Diana Davies Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts.

ASIDE FROM ALL THE solid sociological, historical, and psychological theories explaining why a movement arises at a particular moment and not another, perhaps the only believable one consists of one word: magic. Indeed, beginning in the 1970s, women all over the world were, in serendipity, gathering together in consciousness-raising groups. The goal was to share experiences of our psyches/bodies as emblems of sexist society, to uncover the striking universalities—and in the process, to take control of our lives. The first marches across the Berkeley campus made little impression on me. Nor did the CR (consciousness-raising) meeting we attempted in the commune on Vine Street. It was Anne Kent Rush and Hallie “Mountain Wing” Iglehart Austin who opened my pores to the necessary tasks at hand.

Even before I read such mindblowers as Kate Millet’s Sexual Politics, Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch, and Phyllis Chesler’s Women and Madness or delved into the history of the demolition of early woman-originated healing/ritual traditions, their one-liners clinched the absurdity of dominating women and revealed visions of what should be or what, before the patriarchy, was. Why is the deity touted in today’s religions a man when it is females who enact the definitive creative act of childbirth? Why is there just one overarching deity and not many as in indigenous cultures and ancient mythology? And consider this: the institution of marriage was invented as a way to own and have power over women. Does the constant threat of rape unconsciously function to keep women “in their place”? They took away the stars and tried to divert our distress by giving us diamonds. Is the subjugation of women a mirror of the oppression of animals and land? Is it because at heart we are more expressive of nature?

As our minds were pried open from thousands of years of enforced closure, we began to take action. We demanded equal pay and equal rights. We marched to legalize abortion and “Take Back the Night” from rapists, imagined voting for a woman for President, launched women-owned businesses. We sought out female gynecologists, female Jungian therapists, female architects, female carpenters, female anthropologists, female house painters—all of whom were few and far between. We bought specula to do our own cervical exams. We became adept at telling men when they had crossed the line into sexist behavior. Many women abandoned the male world altogether. We studied prehistory, wrote books, painted canvases, produced what came to be called “women’s music,” and made our own films. We admired each other, fought with each other, made love to each other.

We became.

Kent, Hallie, and I—along with such stalwarts as Sally Gearhart, Merlin Stone, Barbara Hammer, and Charlene Spretnak—gravitated toward the facet of the movement called “women’s spirituality,” critiquing world religions that positioned females as foot-washers to Great Men and God, instead reaching into prehistory to create/recreate the rites of female-based sacredness, ancient goddess cults, witchcraft, and pagan herbal medicines. As French visionary Monique Wittig counseled us: “If you cannot remember, invent.”

And—ladies, get a grip—who could not have experienced instant enlightenment by that first glimpse of a woman in an—oh my Goddess!—all-women rock band, twanging the Man’s Machine: an electric guitar?

Suzanne Shanbaum, 1970s, then of the Berkeley Women’s Music Collective—with electric guitar. Photo credit and courtesy of Irene Young.

SUSAN GRIFFIN: THE ARDENT INTELLECTUAL

(1943–)

We are women. We rise from the wave. We are gazelle and doe, elephant and whale, lilies and roses and peach, we are air, we are flame, we are oyster and pearl, we are girls. We are woman and nature.

—S.G., WOMAN AND NATURE: THE ROARING INSIDE HER, 1978

Susan Griffin is a poet, philosopher, playwright, scriptwriter, and champion of The Sensual. Due to a marvelous ability to drape events in irony and comedic insight, she is also a veritable hoot to be around. Early on her writing was associated with a feminist-invented theme: literature springing from everyday female experience such as being a single mother, subjects that were not considered by male critics to be worthy of the paper they were scrawled upon. But when her play Voices: A Play for Women was shown on PBS in 1975, she won an Emmy Award. Woman and Nature: The Roaring Inside Her came next, in 1978. This was a pioneering prose poem that instigated a feminist interpretation of the relationship of woman and the natural world to patriarchal society; its underlying theme—the connection of female oppression with the exploitation of nature—had not been thought about or discussed before.

It is through this work that Susan became known for the style that she would spend decades developing. She is the mistress of uncommon juxtaposition, reminding us anew that the nature of the human mind is to integrate, to bind together facets and phenomena into the Whole that they in fact make up. Her facile imagination allows her to leap beyond the limits of cause-and-effect logic and reflect how people do in fact experience, think, and make sense of things: as oneiric unfolding.

Each of Susan’s subsequent works deepened this approach. In Pornography and Silence: Culture’s Revenge against Nature, she applied Western culture’s identification of woman with nature, coupled with its urge to dominate both, to pornographic literature and imagery. After the 1990 publication of A Chorus of Stones: The Private Life of War, she invented the term “social autobiography” to describe the approach taken in this volume, as well as in two subsequent books also combining memoir with history; the expression has since become an accepted category of literature. The next volumes in the trilogy are What Her Body Thought, an account of her experience with illness and poverty, and in the wake of 9/11 and the U.S. government’s rescinding of civil rights, Wrestling with the Angel of Democracy, exploring the psychological qualities necessary to sustain democracy.

During this time she wrote a collection of essays called The Eros of Everyday Life and The Book of the Courtesans. She also published two volumes of poetry, Unremembered Country and Bending Home; the script for Berkeley in the Sixties, a theatrical piece written in poetry called Thicket, and a play to be set to music called Canto about massacres in El Salvador.

Susan is a striking woman, her posture presenting both a compassionate sensibility and a sense of purpose. Her blonde (now white) hair often boasts a simple cut with straight bangs, and she possesses a talent for putting together attire that reflects, in her own words, “an understated androgynous style with sudden flares of eccentricity”—like all black covering her body, set off by glasses with brilliant red rims.

She has used this same panache to create a home reflecting her artistic sensibility and love of imagination, filled with mementos of the very themes she has explored in her writing. In the living room a photograph of Sarah Bernhardt performing Camille sits on a bookshelf. Native American art, paintings by her adoptive father Morton Dimondstein, and works by friends adorn the ochre walls. Hand-painted plates from Italy are displayed on a primitive-style cabinet, Moroccan tiles embellish the fireplace, and the French doors invite one to step onto a courtyard shaded by an orange tree.

Most of all, I remember the kitchens in her houses on Hawthorne Terrace and Keeler Avenue. Magical places, these—emanating warmth with their pottery crafted in the 1800s and market baskets bursting with tomatoes and lemons. A heavy wooden table covered by a cloth from the Basque countryside defines the dining area. During a luncheon date, one might imagine that one is in Provence or the American Southwest. Or another century.

To Susan, her house is an art form no different from a poem.

Robert Bly, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, and Griffin, whose poetry appears together in Love is Like the Lion’s Tooth: An Anthology of Love Poems, 1984. Courtesy of Susan Griffin.

I came to know Susan during the high holy days of the feminist movement. What a time we had, rising up as we did in some gloriously inexplicable way, first in our kitchens, classrooms, and communes with consciousness-raising groups, then erupting into Take-Back-the-Night marches, entry into fields like government, law, medicine, art, construction, fishing, and law enforcement; gynecological self-exams, styles of dress not handed down from fashion designers but all our own; with woman-identified books, magazines, radio shows, films, record albums; and through the union lesbians were forging with the emerging gay men’s movement.

It’s hard to recall exactly how we met. Her house on Cedar Street had become a hub for women who were coming into their own through the movement, and there activists/artists/writers like Adrienne Rich, Alice Walker, Michelle Cliff, Audre Lord, and Grace Paley passed through for tea, wine, and always good conversation. When I went there, Susan became a model for me; I had never seen someone my age who owned so many books! Plus she had a room of her own: a tiny writing studio framed in windowpanes adorned by the leaves on the neighbors’ trees. Then there was the time in 1977 when Chrysalis magazine—out of the L.A. branch of the movement—published a chapter of her forthcoming book, Woman and Nature. The read was mind-blowing enough to cause a gal to forget all timidity and call someone up.

However it happened that we met, in the years after our first outing—a walk in Berkeley’s Tilden Park—we became friends with an affinity so synergistic that we might encounter each other at an anti-nuclear fundraiser or in a Northside café and slip into a laughter that rippled on until our jaws ached.

This bundle of humor, soul, brainpower, and drive began life in Los Angeles in 1943. Her mother Sally Williamson’s idea of cooking was often a TV dinner. An alcoholic, twice a week she would cart seven-year-old Susan to bars—mother to go on a bender, daughter to play the pinball machines, sleep on the Naugahyde banquettes, or wait alone and scared in the car. When Sally was drinking at home late into the night, she would sometimes drag her daughter out of bed to level verbal attacks at her.

Susan attributes her familiarity with human dysfunction to this experience, to the constant moving from one family member to the next that resulted from her mother’s personal chaos, as well as to the fate of being born just as World War II and the Holocaust were casting their psychic shadows over humanity. She went to live with her father, Walden Griffin, a fireman at the North Hollywood Station. When she was younger he had taken her trout fishing and horseback riding and, as she reached junior high school, to museums. Tragically, while living with him, another shock shook her world: Walden was killed in a car accident.

At this point fate looked kindly upon Susan. She had been babysitting at the home of Gerry and Morton Dimondstein, sometimes staying with them several nights a week. After her father died, they became her legal guardians, and their influence shaped Susan’s life. They were bona fide Bohemians—he an artist known for his woodcuts in the tradition of Mexican Realism, she an arts educator. And they were ex-Communists. During the McCarthy years, they had fled to Mexico City, where they hung out in the same circles that Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera had frequented, and that muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros did at the time they were there.

Susan and friend Roxanne make a stab at sophistication, 1959 or 1960. Courtesy of Susan Griffin.

Susan went on to study at UC Berkeley—where she protested against the House Un-American Activities Committee, picketed Woolworth’s, and joined a sit-in at the Sheraton Palace Hotel against racist hiring practices. She worked as a strawberry picker for one scorching summer day so that she could testify to a federal committee on labor about farm worker conditions. Then, after a summer in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood where the likes of Allen Ginsburg, Lawrence Ferlingetti, and Diane di Prima had downed espresso, written books, and held poetry readings, she transferred across the Bay to complete a B.A. in Creative Writing at San Francisco State. Afterward, she worked at Warren Hinckle’s New Left magazine Ramparts. She got married, gave birth to her daughter Chloe Andrews (née: Levy), and returned to SF State to complete a master’s degree.

Around 1986-87 Susan became ill with a strange, unidentified sickness. Knocked out by exhaustion, muscle aches, and joint pain, she began to spend what would become several years of active affliction, close to or in bed. Other people, particularly women—among them feminists Hallie Iglehart Austin, Phyllis Chesler, Kim Chernin, and Naomi Weisstein—were suffering similar symptoms, and at last, against adamant denial by the medical profession and insurance companies, an alarmed minority of researchers launched investigations to understand this fast-spreading illness. The results of their efforts revealed a host of changes in the bodies of the affected cohort: lowered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, brain lesions similar to those found in AIDS and Alzheimer’s patients, high levels of protective immunological titers in the blood, and deficiency of the natural killer cells that normally combat viruses. It was speculated that a virus was the culprit, and the disease was termed Chronic Fatigue Immune Dysfunction Syndrome.

During this pained period of Susan’s life, I occasionally traveled from New Mexico to the Bay Area and stayed at her house—mingling my work activities with picking up things she needed, cooking, and watching films together on video. Stunningly, her perspective on the tragedy was not just personal, it was global. “In a terrible way, no one who has CFIDS is truly alone,” she wrote in Ms. magazine. “Sadly, we are all part of this global process. Those who are ill [are] like canaries in the mine—our sickness a signal of the sickness of the planet. An epidemic of breast cancer, the rising rate of lupus, M.S., a plethora of lesser-known disorders of the immune system.”

Like a heroine in a mythic tale, despite her infirmity, Susan did not stop participating in life. Postmodernism was just arising as the new interpretation of social reality in computerized mass society. It was hard for me to grasp, living as I was in the more rooted environ of a land-based village struggling to preserve its traditions, but Susan had already digested the essence of the new thinking and begun to critique its assertions in ways that would later be written about by thinkers like Noam Chomsky, Melford Spiro, and Charlene Spretnak. As the illness lost its force and she could concentrate better, ever so emblematic of the feminist axiom “the personal is political,” she penned What Her Body Thought about the experience.

And she had lovers. “The hope you feel when you are in love is not necessarily for anything in particular,” she wrote in What Her Body Thought. “Love brings something inside you to life. Perhaps it is just the full dimensionality of your own capacity to feel that returns. In this state you think no impediment can be large enough to interrupt your passion. The feeling spills beyond the object of your love to color the whole world. The mood is not unlike the mood of revolutionaries in the first blush of victory, at the dawn of hope. Anything seems possible.” During the early 1980s Susan loved and lived with writer Kim Chernin. In 1989 she fell for Tikkun publisher Nan Fink, and they renovated Nan’s house—Susan building a light-filled office and bedroom by the back rose garden and Nan using the older front side of the residence.

Needless to say, the humor, soul, brainpower, and drive unfurl still. Susan has finished a novel called The Ice Dancer’s Tale about an ice skater from California who, with the guidance of a shaman from the Arctic, “creates an ice dance about climate change that transforms the consciousness of anyone who sees it.” Her goal for the coming years is to complete an epic poem inspired by the Mississippi River, and, true to her roots in the women’s movement, she has begun a nonfiction work about misogyny and the threat of fascism.

LUCY LIPPARD: SOCIAL COLLAGIST

(1937–)

Art must have begun as nature—not as imitation of nature, nor as formalized representation of it, but simply as the perception of relationships between humans and the natural world.

—L.L., OVERLAY, 1983

Lucy Lippard sends postcards. By now there must be enough of them—penned in near-illegible scrawl and mailed to the four winds—to fill an exposition at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. Such an exhibit would be emblematic of Lucy’s originality. Officially known as an art critic, in fact her roles span from cultural intellectual to street rabble-rouser, from twenty-plus-book author to hands-on curator, from university lecturer to radical political activist. She is a woman so crossover inventive that she has been dubbed not just a bystanding commentator on art—but a “Dada-esque strategist.” Or, as she might say, a social collagist.

Aside from her name festooning the masthead of the New York feminist magazine Heresies, Lucy became a reality for me in Susan Griffin’s living room on Hawthorne Terrace in 1983. Here was her new book, a photographic text—a prose poem, really—revealing the similarities of contemporary women’s art with ancient creations of Paleolithic, Neolithic, and indigenous peoples. Overlay was about the most relevant piece of research to hit the bookstores I could have imagined. In the women’s spirituality wing of the feminist movement, we were focused on unearthing pre-patriarchal times when women were honored and held valued social positions, when the moon as reality/symbol held equal influence as the male-associated sun. We were steeped in the cave paintings of Lascaux, the Venus sculptures, the figurines of matriarchal Catal Huyuk, as well as the circular stone construction at Stonehenge—and now here was evidence of the unconscious mind of the twentieth century reiterating these earlier archetypes in painting, photography, and earth sculpture.

In 1973 Lucy’s insights about conceptual art as documented in Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 had flung her into the track lighting of the national art scene. Just as her topic was controversial, so was her approach. The book is a photo poem, a bibliography arranged chronologically, between which are inserted fragments of text, interviews, documents, and artworks. Lucy had written five books before: works on Philip Evergood, Dada, Pop Art, and Surrealism, and a collection of her art criticism. By the mid-1970s she was covering such developments as land art, minimalism, systems, anti-form, and feminist art. “Conceptual art, for me,” she wrote, “means work in which the idea is paramount and the material form is secondary, lightweight, ephemeral, cheap, unpretentious and/or ‘dematerialized.’” Linking changes in American society such as the eruption of the civil rights, women’s rights, and anti-Vietnam War movements to their ramifications in artistic expression, her insights offered social context to the task of understanding such otherwise inscrutable artists as Yoko Ono, Robert Barry, Eva Hesse, and Lawrence Weiner.

Reminder of Tierra Amarilla Land Grant fight in New Mexico, summer 1998: Lucy’s photo of a creative billboard near Tierra Amarilla, which she mailed to me as a postard. Courtesy of Labadie Collection, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Back note on Lucy’s photo postcard. Courtesy of Labadie Collection, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Meanwhile, Lucy herself was taking to heart a truism of the conceptual art movement: life itself is as much a work of art as a painted canvas or a sculpted chunk of marble. She was plunging into the political movements of the times and has been involved ever since. In a 2006 interview with artist/curator Julie Ault, Lucy wryly recalled, “This was … a point in my own life when I couldn’t sit down at a table with people without starting an organization.” A believer in collaboration whether in art or politics—what she terms “social collage-making”—she was a co-founder of Ad Hoc Women Artists Committee, Political Art Documentation/Distribution, Heresies, Artists Call against U.S. Intervention in Central America, as well as the Women’s Slide Registry and two performance-art street troupes.

Lucy was born in 1937 in New York City and raised there as well as in New Orleans, New Haven, and Charlottesville, Virginia—the daughter of Margaret Cross Lippard, an energetic liberal involved in such issues as affordable housing and race relations, and Vernon Lippard, dean of medical schools. The only child of two voracious readers, she decided at an early age that she wanted to be like the people behind the books: a writer. She graduated from Smith College in 1958 and New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts with a master’s in art history in 1962.

I met this incisive mind when, by happenstance, we both moved to northern New Mexico. She built her tiny eco house in Galisteo in 1993. When I asked her about her vision for such a bold project, she surprised me.

“I built it with no vision whatsoever,” she said. “One guy called it ‘the shack by the creek.’ It has expanded a lot since the original 16’ × 24’ footprint; there’s now a book-and-paper-inundated workroom and a tiny guest room. And the trees I planted have grown. I love the interior—a light-filled room with high ceilings and a sleeping loft. It reminds me of loft living in NYC where, after escaping from East Village tenements in the 1960s, I spent most of my adult life. I’m still off the grid, but I’ve stopped hauling water now that I finally got on the community system.”

The Heretics Collective of Heresies magazine, 1977. Courtesy of Lucy Lippard.

When the house was finished enough to move in, Lucy proceeded to become a member of the partly Hispano, family-oriented desert village. Again boldly, she launched El Puente de Galisteo, a newsletter aiming to preserve local identity against the invasively gentrifying forces of economic globalization. Meanwhile, she became a Research Associate at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture and a member of both the Galisteo Archaeological Sites Protection Act working group and Galisteo’s Community Planning Committee and Water Board.

Lucy is a petite, athletic woman, maybe a tad like the roadrunners that speed across the upland desert. Wisps of salt-and-pepper hair fly around her face like ideas leaping into flight, her thick eyebrows add a hint of distinction—and she loves to hike.

One summer day we made a trek under New Mexico’s turquoise cathedral of sky to see the petroglyphs in the Galisteo Basin. Dodging red rocks and fissures of erosion, she told me about New York’s feminist art movement of the 1970s, a period she described as “one of the most exhilarating ongoing experiences I’ve ever had, and it changed my life.” Aside from working in the Heresies collective, she was a founder of the bookstore/gallery Printed Matter. Its purpose was to publish and sell artists’ books that would offer “the page as an alternative space,” hence lifting art out of the sole domain of educated museumgoers to a wider audience. She was so dedicated to the intention of the project that she refused to include for sale her own “weird little novel” I See/You Mean because it didn’t fall within the definition of an artist’s book. I told her that someone should write her biography, and she shrugged off the prospect with characteristic self-deprecation and humor.

She was always doing that, shrugging off praise. The truth is that, during the years I have known her, she along with partner anthropologist Jim Faris were forever soaring off to give a lecture, receive an award, attend a meeting, or accept an honorary degree. “I’m as hectic as ever. Now we have to go to Australia,” she would explain as if the trip were a dreaded burden.

Lucy’s Galisteo Fire Department shot, 2001. Photo credit: Richard Shuff. Courtesy of Lucy Lippard.

But one trip was never a burden. That was the annual jaunt to “summer” in Maine. Lucy has gone to Kennebec Point in Georgetown, Maine every single year of her life. Being the ever-active archivist, she does not just go boating and hiking and read novels like the other “summer people”; she’s become something of a historian of the area as a gift to the generations whose roots are implanted in the seacoast soil.

Her 1997 book The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society is a tribute to the paradoxical urge toward having a sense of place while moving from locale to locale in an itinerant society. The book boasts two simultaneously running displays of text plus many illustrations with lengthy captions. The main text consists of a discussion of issues such as historic preservation, mapping, archeology, photography, cultural differences, toxic contamination, and today’s public-art movement. Along the top edge of each page runs ‘’the vein of Maine”—Lucy’s personal observations about Kennebec Point and how the issues highlighted in the main text play out there. Then, throuout the book, are photographs of place-based art, with captions that relate them to the same issues. The point—and clearly the way she herself integrates the demands on a person who has lived in, come to know, and loved many places—is to be receptive and accountable to the place where one finds one’s self.

Speaking of accountability to place, shortly after its publication in 2014 Lucy sent me a copy of Undermining: A Wild Ride through Land Use, Politics, and Art in the Changing West. In this essay she uses the same twist of thinking being developed during the days of Heresies in which disparate phenomena are linked by history, theme, or place—and thus revealed. The starting point is gravel pits in the U.S. West as a metaphor for the tragedy of what is happening in this portion of the continent. The journey includes Galisteo, Santa Fe, and the Navajo Nation as well as September 11’s Ground Zero in New York City, the Nevada nuclear bombing range, and Hoover Dam in Arizona. Each locale is elucidated as a face of contemporary, capitalist-fueled perception of land—what one might call unintentional “art,” contrasting with the deliberate land art that poets of imagery are creating to draw attention to the madness of seeing land as inanimate, useful, and disconnected from consequences.

She and I have shared not just place, but time; we both celebrate our birthdays in the spring. Aside from meeting for the occasional goblet of wine at La Fonda Hotel in Santa Fe and the yearly Thanksgiving fests at Sabra Moore’s Abiquiú abode, our birthdays bring us together. She was born in 1937, I in 1947—so I look to her for advanced notice of the twists, turns, triumphs, and potholes on the road to aging.

Needless to say, to celebrate, we send postcards.

SABRA MOORE: APRONS AND ART

(1943–)

I grew up with the tinges of historical forces at play within my own family—racial secrets, violence, war, labor, sexism and class were background forces that have motivated me as an artist and activist….

—S.M., LETTER TO CHELLIS GLENDINNING, 2015

Sabra Moore made the same trek from New York to New Mexico as her co-conspirator in the feminist art movement, Lucy Lippard. Specifically, she moved to a desert mesa overlooking Abiquiú where the great (but reluctant) icon of the feminist movement—Georgia O’Keefe—had lived and painted decades earlier. Sabra and her partner, painter Roger Mignon, bought the land in 1989 and made the leap across the continent in 1996, handcrafting their adobe/straw-bale house as if it were a work of art.