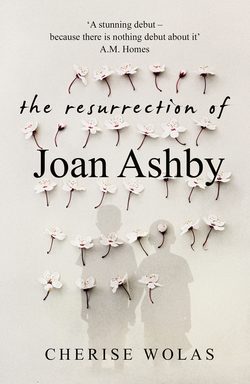

Читать книгу The Resurrection of Joan Ashby - Cherise Wolas - Страница 10

BETTINA’S CHILDREN

ОглавлениеWhen Bettina was twelve years old and already half an orphan, her great-aunt—the aunt of her still-living father—gave her a series of books that told the story of Nurse Claire Peters. These books were not picture books; nonetheless Bettina could picture Claire, bright in her white uniform, beautiful despite the small white cap atop her lush blond hair, walking hushed hospital corridors, entering room after room, moving from bed to bed, her cool hands bringing relief, her changeling voice flowing from blue to violet to purple to the prettiest of greens, different colors for different maladies, the right ones always returning her sick and sometimes crotchety patients to vibrant life.

In Bettina’s mind, Claire’s lips were always shimmering in Claire’s favorite pink lipstick, and Claire’s eyes, observant and alert, the color of purified honey, were opened so wide that she always saw the truth of it all: what people were like when death was upon them. She held their hands then, to bring them forward to the light.

It took Bettina nearly that entire year to read the twenty-book series straight through, wishing with juvenile hope that her curly brown hair would turn as golden and straight as Claire’s, that one day her own lips, thinner than she would have wished, but prettily bowed, would look nice in some similar shimmering pink shade, and when Bettina stacked all the books in her closet, she had decided she would become a nurse.

In nursing school, Bettina found peace with her own uninteresting looks, turning herself outward, focusing quietly, privately, on her natural healing talents; she was often several diagnostic steps ahead of the doctors to whom she was to defer. In the books, Claire never aged or thought about romance, despite being surrounded by handsome doctors, but in her own daily chores as a nurse, Bettina found true love.

At odd times in the staff’s cafeteria, she would see one of the emergency room doctors, the tall ascetic one, but otherwise their paths did not cross: Bettina worked up on a general floor, and he down below, where the world washed ashore its human traumas.

One day, that emergency room doctor bought her a tea, a few days later a lunch. Standing in the cafeteria line next to Bettina, he looked down upon her from his great height and said, “I’m Jeffrey Caslon,” and Bettina nodded and slid her tray up to the cashier, and he said, “Oh, no, I’m paying. After all, this is our first date.” She had not realized it was any such thing.

Some weeks later, on a crisp and starry night, Dr. Caslon led Bettina outside, kissed her with a fervency she returned, and, at his request, Bettina transferred to the emergency room, aligning their shifts. She had not thought she would like her new assignment, but she relished its feral nature, the way the maimed, the shot, the stabbed, and those mysteriously sick arrived in the impure hours past midnight. Six months later, they had a small wedding in the chapel on the hospital grounds. A few months after that, their life then combined into Jeffrey’s spartan bachelor flat, he inherited a substantial sum from an old great-aunt of his own.

When Jeffrey said to Bettina, “Would you consider moving to Africa? Do our part to make the world a bit better?” they were in the emergency room, facing each other across the body of a middle-aged man who, in death, exhibited the true dourness that had infected his soul.

Bettina needed no time to consider. She would be Claire Peters on a grander stage, with money in her pocket, love in her heart, her portable nursing skills freely available to those whose locus of birth created lives rife with disease, with too little to eat, with water that was unclean.

Soon, the Caslons were in a remote part of Nigeria. Jeffrey spread his inheritance around, hiring locals to build them a house, and the clinic they named the Caslon Clinic. They received the first shipments of medical equipment brought, on its last leg, in a rickety plane that landed on a dusty strip beyond the village, used as a playground by the native children for their made-up games.

The Caslons were a great draw; their pale skin, their small features, the certainty they exuded, the smiles they bestowed, all of it warmed the villagers.

When the clinic was upright, secured by a front and back door, a roof that could withstand heat and wind, the freshly married couple got to work. The equipment intrigued the villagers, but intermittent electricity made the plugged-in machines of little use to doctor and nurse. At least the village streets were designated by names, unpronounceable at first, but which gave Jeffrey and especially Bettina the feeling that life, despite how it seemed, was not completely freeform. Neither imagined returning home after the locals befriended them, passed their days hanging out on the clinic’s stairs, on its porch that the Caslons furnished with abandoned chairs.

The Caslons received care packages of food from home which they shared; serious about abandoning all they had once known, their own prior creature comforts, to prove that people could band together and make something better and finer, although impossible to refine. A year into their life in the Nigerian village, Bettina got pregnant the first time, and then again the next year, and the year after that. She was heeding the Nigerian way.

In the right time, each time, Bettina gave birth to three bouncing babies, two boys and a girl. Children who laughed a lot and smiled early and seemed very intelligent and were healthy, so healthy, until they gained their footing and ran with their friends, mingling in the sweetness of childhood with the ebony-bright village children who laughed without knowing the desperate futures only they faced, or so the Caslons believed with a kind purity in their hearts.

Then once, twice, three times, Bettina and Jeffrey peered into dug-out holes, innards tossed up into mounds just beyond, laying each small wrapped body Bettina had birthed, deep down, to avert the scavenging animals capable of digging to China to get what they were after. Each time, Bettina fell to her knees, shocked by what she now shared with the village women; that there was nothing to keep her, any of them, safe. The Caslons were the same as the people they aided, adding their own blood to the heated red dirt.

Neither was religious, and they refused the crosses the Nigerians, thinking they were offering what was right, carved for them. Instead, they asked for wooden placards upon which Jeffrey and Bettina wrote the names of their dead children—Marcus Caslon, Julius Caslon, Cleopatra Caslon—their birthdays, their death days, marking their entombments in an earth that rarely felt the rain, that the wind blew away in devilish swirls of dust.

A month after their last and final child, called Cleo for short, was laid to rest at the age of three, the same tender age as the others, Bettina stood at the graves of her flesh and blood, and the hot, hard sun seemed ludicrous; death deserved darkness for more than a few hours. She wanted nothing to do with what Jeffrey was offering—a try for a fourth. What was the point of the inevitable prolonged suffering parents and child would endure? Marcus, Julius, and Cleo all set afire by temperatures that traveled up to one hundred and eight, that could not be reduced or assuaged. Three times, sitting by the bedsides of her loves, the fruits of her labor, Bettina had watched the skin peel free from their bones in strips as translucent as butterfly wings.

Jeffrey, brave and stoic, sure their sacrifices were part of his mandate, would not hear of leaving it all behind, this godforsaken country, as Bettina was then calling it, these people who demanded too much. When the rickety plane carrying Bettina was airborne, its small windows blinded by the light, Jeffrey wondered if, from up there, she was looking down, could see his hand raised, the tears on his cheeks.

She did not return to the American city of her birth, where her father had raised her, such as he could, where Jeffrey had plucked a young nurse filled with belief from obscurity, leading her into adventure, then into something else that Bettina knew should not be identified. She never sent a card or picked up the phone to call Jeffrey’s parents, his sisters, to say there had been a rift in their marriage, that he remained in the world she had fled from. Instead, Bettina chose a big eastern city where winters were racked with high drifts of dirty snow. Her impressive nursing skills, her experience with diseases most of the doctors had only read about in medical books, allowed her to orchestrate her future: a hospital where she was given free rein over the toughest pediatric unit, with skeletal children who would never enjoy a day at the beach, or play with their older siblings, or fall into or out of crushing love. She cared for their deflated sacks of skin and fat, untested muscles long gone, bound up in heavy blankets, tiny tubes inserted into their tiny veins, watched over by their parents, huddled and grieving, sitting close by, holding tender sets of fingers.

It was too late to save these parents from suffering as she had, though Bettina never kept them at arm’s distance. She embraced the parents, she cried too when tears swamped their eyes, and she did what she could to make her sullen, saddened babies, her toddlers with a couple of front teeth peeking through swollen gums, comfortable.

Nigeria had taught Bettina to recognize the irrefutable line, how once it was crossed, it marked the end of time. In the large eastern hospital, when she saw the line crossed, when the parents had gone to the family room for a few hours of desperate sleep, Bettina sent her little foregone loves on to whatever world lay beyond. She emphatically did not view her actions as murder; she was no killer, but a loving nurse whose own maternal history had changed her initial reason for being: when there was nothing left to do, she heeded her training and made the suffering stop.

When they came for her—

Fictional Family Life, Ashby’s immensely praised second collection, is a razor-sharp look at family life, focused around a teenaged boy who may, or may not, have tried to kill himself. That unclear violent act is dissected by two sets of narrators: Simon Tabor’s family members, and the doctors and nurses who put him back together again. While the truths and lies of real life are debated, broken Simon Tabor remains in his hospital bed, in an inexplicable coma, and in that netherworld, he creates his own alter ego, a boy his own age, also named Simon Tabor, who is stuck in his room, creating his alter egos—boys who live the fantastical lives both Simon Tabors wished for themselves.

The following excerpt is from “I Speak,” the only story in the collection in which the real Simon Tabor speaks for himself:

This is the only time you will hear my voice, the only time I will speak to you directly. Right now, I am on a table in an operating room and the doctor and nurses are racing around, working hard to repair the damage I have done to myself.

This isn’t one of those stories—about a near-death experience that changes one’s life, or a revelation about what happens when a person dies for some minutes and is revived. I haven’t died and I won’t. I am completely aware of everything going on around me, how, in their gowns and masks, the medical staff look like superheroes protecting their real identities.

Dr. Miner has just said, “Scalpel,” and is now slicing into my skin, a zzzziiiippppp through the various levels of dermis, then a sucking sound, my blood spurting all over, and he says in this tight voice, “Clamps, now,” and then he’s clamping off various of my blood vessels that are dancing like beheaded snakes. Even with all the activity, my hearing is so stupendous I can tell Judith, RN, is sorting through the plates and screws, and Louise, RN, through the pins, trying to find all the right-sized pieces of hardware Dr. Miner will soon insert into my body.

Hours from now, when Dr. Miner finishes stitching me physically back together, I plan to slip into an unexplained coma, and stay there for a good long time. I am looking forward to it. I think it will be fun, and restful, and give me time to think.

Plus, in the five hours I’ve already been in this operating room, I’ve discovered my own superhero power: I have the ability to know what’s going on in the private lives of these people caring for me.

Like Dr. Miner, for example, he’s setting my shattered left femur now, will do the right femur next, and while he’s focused precisely on what he’s doing, another part of his brain is back home, where just hours ago the woman he loves told him that she doesn’t love him, that he is lousy in bed, and that she has been sleeping around. He doesn’t want her to pack and leave him, but what else is a real man supposed to demand? I agree—the traitor has to go, who needs to love someone frightful like that?—but I can tell Dr. Miner is weak and this betrayal will affect him for the rest of his life.

And the anesthesiologist monitoring my pulse, calibrating my state of unconsciousness, she’s debating telling her husband she wants a boob job, to reduce, not to inflate, and she knows he’ll put up a fight, the way he loves doing all manner of things to them, stuff she can’t stand, and I can see in my mind the things her husband likes to do. I think the anesthesiologist might be kind of squeamish, because it all looks cool to me.

And Dr. Miner’s right-hand nurse, Judith Sonnen, she’s handing Dr. Miner a plate to screw into my femur, and she’s got a prayer running through her head in a gobbledygook language, praying not for me but for her own strength. Born Esther Sonnenberg, her parents turned into evangelical Baptists when she was a kid and changed everyone’s names, and Judith Sonnen thinks she may want to be the Jew she was born to be, reclaim her name at birth.

You can see, right, why I might not want to give up this power I’ve developed out of the blue.

Eventually, I’ll be wheeled into a hospital room, already deep in my coma. Here’s the warning. When I’m in my coma, you will hear theories about why I did what I did, posited by those who love me and will rarely leave my bedside: my parents, Renata and Harry, my sisters, Phoebe and Rachel, our occasional housekeeper, Consuela, and my dog, Scooter, as well as theories tossed about by Dr. Miner and the nurses, Judith and Louise, who feel a sort of love for me too, because they have seen inside my body, are invested in my slow progress back toward life.

But don’t believe any of them because they will all be wrong.

I was not depressed, psychotic, delusional, did not think I was Christ, or some disciple, or a prophet whose name I can’t pronounce. The blood tests will prove I wasn’t on drugs. I will, however, be on great painkillers for close to a year.

I have already conjured up my alter ego to entertain me during the silent months to come. His name is also Simon Tabor, and he’ll tell you about his life, and about the alter egos he—or rather I—create. Four boys, the same age as us, who live the kinds of lives we want to live. Both of us Simon Tabors stuck in rooms for very different reasons, yet sharing the same desire to experience other lives.

The bottom line is that my plan to fly did not go as expected. A lapse in judgment, I agree, and a question to be resolved another day. I’ll have plenty of time to figure it out, but here is Dr. Miner leaning over me—

It is impossible to overestimate the titanic interest that attended Ashby’s every move during those years when her collections dominated. In an era that pre-dates our current obsession with celebrity, her stunning success at such an early age, which also included receipt of a PEN/Malamud, and a Guggenheim, made her a phenomenon, one of the first literary celebrities on a modern-day scale. For a time, until she disappeared into small-town life, photographers often followed her—to the Korean grocery, the Laundromat, on her walks through the city.

Equally amazing is that Other Small Spaces and Fictional Family Life are now in their twenty-fifth and twenty-third printings respectively.

In William Linder’s first Wall Street Journal interview with Ashby, when she returned from the Other Small Spaces book tour, her remarks display an innocence at odds with the splendidly dark nature of her writing.

“I took a temporary leave from Gravida Publishing, locked up my apartment, and was sent to Columbus, Fargo, Salt Lake City, Nashville, Austin, Seattle, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Boston, Chicago, and Newport, Rhode Island.3 I was raised in a smallish suburb of Chicago, so before going on this tour, I had only seen that Midwestern city and, of course, New York, where I live. Seeing America as a new author was an incredible experience. I read to eager audiences, signed stacks of my books, was interviewed in hotel lobbies, in white-linen restaurants, in diner booths with gummy tabletops. I was photographed in local libraries and bookstores and, for some unclear reason, photographers posed me outside, on the shores of Lady Bird Lake, on a Newport dock in front of gleaming yachts, with my toes in the sand and the Pacific Ocean behind me, the camera clicking away. Young writer musing is how I imagined those pictures, all pride and intention, eyes lowered against the sunshiny rays, the wind whipping my long hair around my throat until I was sure I would choke.”

The New York Review of Books conducted an in-depth interview with Ashby that coincided with the publication of Fictional Family Life. Much was written about her following Other Small Spaces, but in the NYRB interview, for the first time she disclosed certain salient facts about her upbringing that helped explain her authorial precociousness, as well as the characters she wrote about, the fine line of their actions.

“I was an early reader, maybe because I was an only child, literally made by people not at all interested in me. It seemed to me that I had crashed through some kind of atmospheric orbit, landed on a planet where I definitely did not belong, and was not wanted, left huddling out in the cold, beyond the tight parental circle of two. Whether that circle was forged before I came along, or as a result of my presence, I’ve never known. What I did know was that they had no idea what to do with me, and I was left to my own devices.

“Most children in such underloving circumstances would act out, or demand their rightful attention, but I was made differently: I interpreted my familial outsider status as an invisible cloak granting me freedom, allowing me entry into a forbidden world where I could hear what was unspoken in the silent spaces and watch the misalignment between people’s words and their deeds. I was seven when I crossed over, began stealing what I saw and heard, grafting my thefts onto people I imagined, whose stories I started writing down. My characters became my people, their worlds, my worlds, and it made me feel whole, happy, and safe. Books gave me succor and my parents’ disinterest set me loose as a writer.

“If I had felt a natural kinship with my parents, who knows what I might have found myself writing about, or whether my work would have been of any interest to others. But my parents are who they are, and my upbringing was what it was, and I, through acclimation and natural constitution, was solitary and watchful.

“The concept of love completely mystified me—it still mystifies me—but I have always seen the darkest emotions with absolute clarity, the depths to which people can so easily descend. I gleaned all that in childhood, saw how the theory played out in my own family. It was a short step to believing we all possess the innate power to inflict great damage, even to kill, with the right convergence of events.”

Ashby acknowledged that her parents did not intend to read her collections. “They have no interest in my work, are completely indifferent to me and my career. When I was ten, I handed my mother a story I horribly called ‘The Meaning of Love.’ With that title, no doubt she hoped to read something that might convince her I would end up a normal girl. But the story was about the opposite of love, and she quailed in the face of those I gleefully murdered, her only comment: ‘I don’t understand what goes on in your head, Joan.’ She never again asked to read anything that came from my pen. My father never asked once.

“Their disinterest was my great luck as a writer. I have never felt compelled to harness myself because I have not been burdened by what they might think. My characters fall apart, immolate, decimate, grapple with the sinister impulses in their natures, injure themselves and others, kill too, and I am free from parental approbation. It is a way of writing that I highly recommend.”

When Linder interviewed Ashby again, after the Fictional Family Life tour, she had this to say: “My publisher sent me around the United States for the second time, which I loved, and also to London, Paris, Rome, Zurich and Geneva, West Berlin, Cairo, and Istanbul. Switzerland struck me as odd, but apparently the precise Swiss secretly enjoy reading about lives that are not neat at all. West Berlin was distressing, knowing what was on the other side of the Wall. Cairo and Istanbul seemed like random choices until I was told that FFL was a runaway bestseller in Egypt and Turkey, something I could not have imagined. Of course, I never imagined that either of my books would experience the great success that they have.

“But to answer your question, Mr. Linder, traveling for Fictional Family Life was something else entirely. This was my first time abroad, and being feted in those international cities was exciting. However, there were palpable differences between the two tours, because with FFL, suddenly I was no longer a debut writer, introduced instead, and uncomfortably, as the young and revered Joan Ashby, my name enunciated worshipfully, as if it were suddenly coated in a gorgeous veneer that should have taken centuries to develop. And everyone made clear to me—my agent, Patricia Volkmann, and my publisher, Storr & Storr, the foreign publishers of both my collections, writers I met, journalists who interviewed me, critics who have written about my books—that my first novel is eagerly expected. Of course I feel the pressure. But my own expectations for what I can accomplish likely are grander than theirs, and I feel confident about meeting them.”

During the years when her star shone so brightly, some journalists were intent on positioning her as a feminist writer, though she refused such a limiting designation. “On that particular subject, I will say only this: I am a writer.”

Indeed, when Ashby wrote about so-called feminine themes, such as love, family, and domesticity, she twisted such themes entirely, reversed them, turned them inside out until they were virtually unrecognizable. In Other Small Spaces, her male and female protagonists are children, teenagers, or adults, all ingrained in their lives, and, to various extents, flawed, hurt, suffering, vengeful, angry, kind, thoughtful, sometimes brutal with others and gentle with themselves, or vice versa. The scenes might be domesticated, but she was not writing merely, or solely, about domestic arrangements. With extraordinary beauty and burly power, she wrote about people of both sexes clawing their way out of stifling, smothering, or shrinking worlds, some believing wholeheartedly in living what Ashby called an out-there life, meaning a specifically determined life that did not conform to modern-day expectations. Other writers took Ashby up as a cudgel, as proof that being female did not lessen the impact of the work.

She also claimed male territory as her own, especially in Fictional Family Life, where she wrote deeply about Simon Tabor’s multiple versions of himself, and the adolescent boy’s self-imagined cast of make-believe fathers. In writing those daring and unpredictable fathers, juxtaposed also against Simon Tabor’s real father, a self-destructing stockbroker who finds personal redemption as an insurance broker in the Bakersfield desert, she displayed her dazzling virtuosity, somehow both luminous and formidable.

Ashby writes for the sake of the work, although, when pressed, she did not apologize for seeking her own lasting place in the world of letters. In a 1988 interview with Esquire, she said, “It’s not actually possible to write for an audience. Or at least I can’t. I write for myself and hope others may find themselves in my work. It takes a lifetime to attain a writerly expansiveness, and finding an audience is the least of it. Of course, when I’m honing a story for the thousandth time, I admit my desire for that audience may have become conscious. I labor to be in charge of my own material, and if that hard work allows me to sit at the table with other serious, great writers of this and past generations, I don’t shy away from that. Why would I? I write for myself, but I seek to be read, for the work to be deeply felt.”

The Linder interviews and the Esquire interview are also interesting because Ashby limited the questions she was willing to answer to her childhood, her life as a young writer, her literary dreams. She never discussed her current personal life. As a result, many of her fans were shocked to learn she had married just before the international tour for Fictional Family Life commenced.

In early June 1989, under the bright lights of television cameras, Ashby read to a sold-out, standing-room-only crowd at Barnard College. Afterward, many female members of the audience inundated her with questions about her recent marriage, expressing their dismay. We note that the following transcription of Ashby’s remarks are set out here for the first time. The program that aired on PBS did not include these revelations.

“Sometimes I worry, too, that what I have done will end up disappointing myself. Beware of friends encouraging you to take a break from your writing, telling you to have a little fun and celebrate your success, if only for a long weekend. Beware, because your life may move in ways you didn’t expect, or want, suddenly hallmarked by the seemingly traditional. In other words, beware of finding yourself living an unintended life.

“I don’t normally divulge the personal, but it seems right to share how I ended up here. A road trip a couple of years ago with friends, fellow—or rather female—editors at the publishing house where I used to work. They chose Annapolis because the Naval Academy was there; all those strong and handsome men excited them. I wasn’t interested, I had my focus. But there we were on the July Fourth weekend, in a bar on the waterfront promenade. My friends let themselves be swept away, but I held on to my place at that bar, thinking I’d stay and observe and slip back to the motel, make a few notes for the future. Then a man introduced himself to me and his extravagantly long hair was eccentric among all those shorn skulls of the naval cadets.

“If I had figured out immediately the kind of man he was, things might now be different. I believed then, as I still do, that my writing benefits from my perceptual abilities and my observational skills. So I absorbed this man’s long hair, his long fingers, his long eyelashes, his romantic brown eyes, and I wondered what a painter or a sculptor, some kind of artist anyway, was doing in this naval bar. He struck me as likely leading a peripatetic life, attributing his unsteady schedule to a muse. But my snap denouncement of him was completely wrong. He was at Johns Hopkins, a doctor in the midst of a fellowship, specializing in rare eye surgeries, enraptured by his ability to help people see their worlds again. He was home for a visit with his vice admiral father, at the bar taking a breather from the old man who was still angry that his son had refused the navy.

“Groan now, because I know you will. He bought me a drink and said that when he completed his studies he was moving to a small town that had a world-class research hospital and lab where he would work on his theories for revolutionizing neuro-ocular surgery. What I heard in all that was small town, and I could not imagine anyone wanting to live in such a place. Two drinks in, I stupidly agreed to see him the next day. That turned into two more days spent together. I could see he was infatuated, but the notion did not fill me with unalloyed pleasure. I was not looking for love. Love was more than simply inconvenient; its consumptive nature always a threat to serious women. I had seen too often what happened to serious women in love, their sudden, unnatural lightheartedness, their new wardrobe of happiness their prior selves would never have worn, the loss of their forward momentum. I wanted no such conversion, no vulnerability to needless distraction. Since childhood, I had kept my literary ambitions at the fore of my mind.

“On the trip back to New York, I refuted my friends’ belief that love had found me. ‘He’s a doctor who looks like a disheveled artist and neither he, nor any man, figures into my plans for my future,’ I told them, in those or similar words, and I meant it.

“I held my ground against his romantic campaign of phone calls and handwritten love letters for a while, and then I agreed to see him again, on my own territory. [Much laughter here.]

“Come on, most of you probably would have done the same thing! I didn’t anticipate our coordinated humor, or our perfect balance in those other meaningful ways. After that, every third weekend, he took the train to New York or I took the train to Baltimore. I had assumed I would live happily alone, passionately consumed by the lives of my imagined humans, but for the first time, I found my thoughts synced to those of another. I had never before experienced that with anyone. Being cherished took me longer to acknowledge and accept. He makes me kinder, more generous, when I step out into the world, and there is a gorgeousness in seeing oneself in the loving reflected glow of a worthy other.

“When I finally settled into the seriousness between us, the palpable love, it struck me as rather marvelous. Obviously, I put up serious barriers—my work comes first, no children, we’ll consider a dog—but he wasn’t put off, not even during this insane year with the publication of Fictional Family Life and my constant absences.

“What I also discovered is that I’m having no problems writing what will follow Fictional Family Life, thrilled that the work contains no words about either of us at all. [Much laughter here.]

“You laugh, but I’m incredibly relieved. The idea of mining material straight from my own life is abhorrent to me. I have no desire to write self-indulgently. I say this with appropriate trepidation, but I think love might make me a better writer, a writer able to delve even more deeply into what makes people human, because I am now experiencing the full range of emotions. If nothing else, discovering I have a speed, other than breakneck, has been revelatory.

“We’ve bought a small house in a place that calls itself a town but is no bigger than a village.4 I’ve been living there for exactly two weeks, most of my time spent in a spare bedroom that is now my study, continuing to work on my first novel. And no, I won’t tell you what it’s called or what it’s about.”

The novel Joan Ashby was working on in her Rhome study in 1989 remains a mystery, for she has not published anything since Fictional Family Life. The Barnard event would be the last time Ashby read or spoke publicly, and thereafter she ceased granting interviews of any kind. On that evening, twenty-eight years ago, Ashby was wholly unaware that she, newly married, was pregnant.

(Continued after the break)