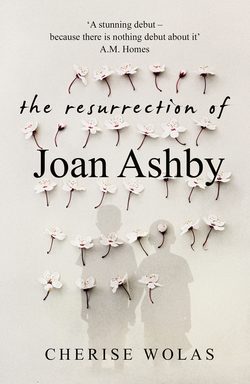

Читать книгу The Resurrection of Joan Ashby - Cherise Wolas - Страница 18

6

ОглавлениеIt was Fancy’s fourth month with them when Joan plugged in her typewriter, rolled a piece of paper onto the platen, put her hands on the keys, and wrote a first sentence, then a second, then the typewriter keys were quietly rat-a-tat-tatting, sounding to her like a symphony, her heart beating to the rhythm, her breath falling in line with the tune.

Each word she put down shined, imbued with love for her son and for her husband, and with appreciation for this nanny they hired who already felt like a member of the family Joan never wanted. But the words belonged to her alone, and for the first time since becoming a mother, Joan found herself on the firm ground she inherently recognized. She was, she realized, out of the abyss.

During every one of Daniel’s naps, she secreted herself in her study, calming Fancy when she worried that Joan was wearing herself out, was planning on weaning the baby too quickly.

At first, she was writing about a quirky young woman like Fancy, but within days Fancy disappeared, and Joan was writing about babies. Unusual babies, rare and wondrous, odd and strange, philosophical babies who could opine about almost anything. Her creations had turquoise hair, or ears meant for elephants, or toes and fingers fused together that did not alarm but instead allowed for happy paddling in baths and ponds, or hearts that beat outside of their chests marking their levels of happiness, or an ability to speak multiple languages immediately after letting out their first cry. Their traits, their characteristics, were elegant and weird, and varied from story to story.

The babies in “The First Play Date” compared their experiences while they had been inside, discussing whether the wombs they had chosen to inhabit had been cramped or roomy, whether the water had been too cold or just right, about the one-eyed sharks some saw coming at them nightly, while others said they never saw such a thing, just used the time to practice their acrobatics.

In “Our Needs, Our Dreams,” babies in a hospital nursery fervently discussed the difficulties they were having managing their miasmic ids, their enormous desires to come first, to always be heard, to be fed at the first pang of hunger, wishing someone, their parents or the nurses, understood their incomprehensible babble, for they had so many nightly dreams that needed immediate telling.

In “Twins,” a solitary baby in his crib stared up at the fluffy white clouds he could see from his window and soliloquized about how it felt watching his twin die in their mother’s womb, when just moments before they had been playing a chatty patty-cake together, how awful it had been barreling down through the tunnel alone, leaving her behind, a pale specter beginning to disintegrate.

In “Role Reversal,” the babies effected a cataclysmic shift that turned mothers into fathers and fathers into mothers, and in “The Miniature Caretakers,” the babies wound up nursing and feeding and rocking and singing to the adults meant to care for them.

In every one of the stories, Joan’s creatures unspooled odd familial tales. She called them her Rare Baby stories, but they weren’t written for children.

She was surprised by the new lightheartedness in her writing. So much of her earlier work was about the damaging events that bowled her people over, and she had thought Daniel’s birth would intensify her dark view of the world, that she would envision tragedies that would take Daniel away, but she found she did not fear for his safety at all, had faith in her newfound abilities, and in Fancy’s and Martin’s, to protect him.

Despite the disturbing qualities of her fictional babies, they were additional proof that motherhood was continuing to soften her. She had feared the opposite would occur, that she would become rigid and unyielding, as her mother had been. Instead, because of her own child, her writing was veering in a new direction; it was an unanticipated surprise.

Joan wrote five, then eight, then ten, then fourteen of the Rare Baby stories, and there were so many more bouncing around inside of her brain, in her heart.

“Tell me about them,” Martin said. But the work was too new, and strangely personal, and Joan gave him no details; she did, however, tell him the truth: “Their sole purpose is just to get me working again, amidst the glorious mess of my reconfigured life,” and he laughed the way she had hoped he would.

When Daniel was fussy at naptime, he settled when Joan leaned into his crib, stroked his face, and said, “It’s time for a Rare Baby story.” She took the recliner, and Fancy, hunched down on the short stool, reached through the wooden bars to hold Daniel’s hand, her small hazel eyes already focused at some distant point, her mouth, with the gap between her front teeth, already opened, breathing excitedly about what was to come. One afternoon, Joan said to them, “This is the beginning of a story called ‘Speaking in Tongues.’”

Since nearly the beginning of time, there were four inalienable truths about the Eves.

The first truth was that every single member of the family was female. There were no grandfathers, fathers, uncles, brothers, or nephews; there never had been. Each woman, on her own, without the need for any man, gave birth to a single child, and it was always a girl. It was Eve lore that their pure matriarchal line was a result of DNA, or caused by an undiscovered aquatic element, or was passed down in dreams from Eve to Eve, generation after generation.

The second truth was that the Eves had a specific, hallowed mission, every single one a musical thanatologist, playing harps or violins or cellos or flutes or lutes or using their lush a cappella voices as prescriptions rather than performance. Musically ushering the dying into the next world, or providing a quiet space for those facing eternity to reflect, ponder, rest, and muse on the meaning of life and death. Some of the dying were recipients of a single musical vigil, their time so near and at hand; others were treated to several, over weeks or months, calibrated to diagnoses, blood pressures, the insistence of diseases, the contraction of organs, the shifting of breaths, before they were claimed. Patients called the Eves angels of mercy, protectors of souls, but they were merely women curiously suited to the work, able to provide profound human connection with their invulnerable flesh, the way suffering flowed right through them without creasing their hearts.

The third truth was that every single Eve came out of the womb with identical features: long brown hair that fell to the waist, brown eyes that watched everything, and seashell ears that heard the slightest of sounds.

The fourth truth was that all Eves spoke early, by their eighth month. Training to become a musical thanatologist took a very long time, involved classes in music theory, in appreciation, in instrument and voice preparation, in rehearsal time, classes too in the workings of the body, in anthropology, in the history of death, potential sources of an afterlife. Over the eons, evolution unique to the Eves had shaved away the extra sixteen months normal children required to find their tongues, their voices, their words, their speech. Any Eve who did not begin speaking in that special eighth month faced an uncertain future, potential banishment from the clan, relegated to an unhappy life among boys and men whose harsh voices could force birds from the sky, turn soft rain into a killing machine, cause floods, famine, disease.

The Eves began with Ruth and wound through thousands of years down to Esther, who birthed Bessie, who birthed Annette, who birthed Willa. Of course, Willa looked exactly like her mother, like all her forebears, but she had sailed past her eighth month of life and had not said a word. Now that her first birthday had come and gone, fear was often in Annette’s heart.

Willa was a good baby otherwise, a calm and still child, but she made no sound, not even a peep, and even when she cried, which was rare, she made no noise, her tears falling silently until they dried up and disappeared, leaving her long eyelashes beaded together, and the faintest silvery trail down her pink cheeks, grains of salt that sometimes her mother licked off.

It was lunchtime on a Tuesday, and Annette was expected at two at one of the hospices on her regular route, a request for a violin vigil, made by the man himself. When he called, he said, “I’m 110, so there’s no time like the present. To be bathed in the sweetness of the violin in the hands of a master like yourself must be one of the loveliest ways to go. I have come to terms with it all and I am ready to close my eyes for the last time, to be taken away by the melody of a nigun, the Baal Shem specifically.” A nigun was the most taxing of soulful and religious Jewish songs, calling upon Annette’s deep improvisational abilities, but the man’s choice of the Baal Shem meant she had centuries of that nigun to follow, its overarching form structured by so many other violinists who had come before her, reflecting the mystical joy of intense prayer.

As she fed Willa the mashed peas she adored, one spoonful at a time, the Baal Shem was soaring through Annette and droplets collected in the corner of her eyes. Any crying by a thanatologist had to occur in advance, but certainly outside the walls of the hospice.

Another spoonful of the green mash and when the food slid in, Willa closed her perfect little cherry-red mouth and swayed with happiness. The kitchen clock never made any noise, but suddenly Annette heard the ticking, turned to look, watched as the second hand stopped sweeping, then moved forward again, one noisy click at a time. She felt her heart flutter, watched the spoon flip over in her hand, a dollop of green landing on the black and white tiled floor. Her head whipped back to her lovely little daughter, and she screamed.

Willa’s unspoiled face had altered entirely, was suddenly abstract. There was her original mouth, the cherry-red one, so pert and lovely, but right next to it, as well-shaped as the first, was a second mouth, the deep purple of an overripe plum.

And then Willa spoke for the first time. From the cherry-red mouth came the words, “I love you, Mommy,” and simultaneously, from the plum mouth, came the words, “You are a witch with a black heart, Mommy, I know what you really think about when you play your music, send those people to death”—

and Fancy inhaled so sharply that Daniel turned his head at the sound and let out a funny little laugh.

There was a timelessness for Joan in the act of creating these stories, a harkening back to when she was a young girl and beginning to write. After the failure of The Sympathetic Executioners, it was a relief to write without thoughts of publication, awards, and best-seller lists. The writing was pure again, the way it had been with both collections. And by reading aloud parts of the Rare Baby stories to Daniel and Fancy, she experienced the youthful pleasure denied her as a child, all that intense longing for a different mother who would have sat on Joan’s bed and read Joan’s stories aloud, exclaiming over what her child had produced. In the nursery, Joan’s good voice floated, and the words of her strange stories rode the quiet air, and something way deep down inside of her was soothed, a release of the anger and hatred she had long carried about her mother, Eleanor Ashby, the force that colored Joan’s earliest memories.

Each time she sat down to work on these stories, she knew they had something specific to tell her, perhaps about how she would be as a mother to Daniel as he grew up, encouraging his creativity, making true the positive effects of the buttercup-yellow paint. She sensed they were not meant to be heard by any others, not to be read by anyone else either.

At least once a weekend, Martin said, “How’s the work coming? When can I read them? When are you going to send them to Volkmann?” He asked these questions, one or all of them, again and again, opening the door to her study while she was working, throwing her a kiss when he finished his querying, until shivers ran through Joan when she heard the knob turning, making her breath catch in her throat.

Each time, she said, “Soon, maybe,” the way she had when he wanted to read pages from The Sympathetic Executioners, then said, “Martin, I need a little more time, then I’ll be out.”

Her husband, brash and brave in the operating room, in his focused research for groundbreaking ocular surgeries, seemed truculent in those freighted moments, before she responded, petulant even, and she felt incapable of explaining—had no desire to explain—the intrusiveness of his endless questions.

One day when they were alone in the living room, Fancy with Daniel in his room, Joan said, “Does it work for you that when you want to talk about your successes or failures in surgery, whether the research is going well or not, I listen, but otherwise I don’t try to burrow into your world, just give you space to move and roam and be on your own, with your thoughts, hopes, and beliefs?”

“You’re wonderful that way,” he said, failing to make the leap he should have been able to make, to see that he was trying to burrow into her world, a place where he did not belong, and the single unspoken sentence jammed in her mind: You’ve got to leave me alone.

For a man so attentive to his patients, aware of their fears and their foibles, how had he forgotten this about her, her need to keep her work to herself? At the very least, when he was home, why didn’t he notice that Fancy never, ever, knocked at the study when Joan was inside? If she thought a sign on the door would do the trick, she would have hoisted that sign right up, written in big black words: MARTIN—DO NOT DISTURB ME, but even that, she knew, would not keep him out. Sometimes she thought the only way to silence his voice, extinguish his interest, would be to stone him to death.

Breast-feeding ended, and bottles began, then rolling over and baby food, then gummed toes, solid food, first steps, and when Joan was not with Daniel or working on her Rare Baby stories while he napped, she and Fancy planted infant red maples, elms, and Cleveland pears around the property’s entire perimeter, a weeping willow tree not far from the house. They hoed and raked the ground, eliminated the weeds, prepared the soil, tilled and fertilized it, then planted Kentucky bluegrass, tall fescue, fine fescue, Bermuda grass, Zoysia grass, and perennial rye, and took turns watering every morning and afternoon from spring to late fall. On weekends, Martin pitched in, allowing Daniel to think he was helping, his small hands gripping the hose just behind his father’s big ones.

In their second year of planting, when the grass was finally fully established, Joan and Fancy figured out how to lay down sprinklers, and turned them on. “The water’s going to be cold,” Joan warned Daniel, but he ran laughing through the arcing sprays. “Look, Daniel,” she said, and he stopped and looked at all the rainbows dancing around their backyard.

Joan and Fancy devised the shapes and boundaries of all the various gardens, marked them with sticks and flags, then got down to work, troweling, fertilizing, and planting lilac bushes, bougainvillea, hyacinth, phlox and poppies, tulips, wild violets, and gerbera daisies, everything in various hues of lavenders and pinks and purples and scarlets and burgundies and white, a field of lavender too. Their first vegetable garden was seeded with carrots, cucumbers, radishes, domestic tomatoes, beans, and lettuce, the vegetable world that thrived regardless of the gardener’s abilities. Near the house, they built the playground Joan had imagined while weighing Daniel’s early extermination. He now had a large sandbox to play in, and a swing set, and a bright-red jungle gym that took Martin three days of hard labor to put together.

In their third year of planting and gardening, all the flowers came up, a riot of blooms. Joan and Fancy took Daniel with them to the lumberyard, bought planks of wood and panes of wavy old glass and the building specifications for a gardening shed. They sawed and hammered, figured out how to make window frames, how to install the glass, and the shed rose up behind the weeping willow tree that was still so small, Daniel shimmying up its baby trunk yelling, “Look at me,” all of twelve inches above the ground. When Fancy went home to Canada for a family visit, Joan painted the shed green by herself and stored all the gardening equipment within. By then, they had a potting table, ceramic planting pots stacked up like mismatched wedding-cake tiers, a large assortment of dinged and muddy trowels, rakes and hand mowers, bags of rich dirt for settling cuttings of delicate flowers into the pots until the new baby plants were sturdy enough for life outdoors. Sometimes, Joan escaped to the shed for an hour of quiet with a glass of wine, lowering a window for an illicit cigarette, briefly longing for the time when she had not created a different story for herself, longing too, for other ideas to flow through her mind, something beyond her rare babies.

Daniel was nearing four when Martin began flying to England, Germany, Croatia, and Russia, requested by private hospitals to operate on their citizens. Against the odds, he was having great success with his newly devised surgery, returning sight to people who lived in an underworld of barely recognized shapes, or no shapes at all.

Joan was on the bed watching Martin pack for his tenth trip abroad—lucky scrub caps, the funny clogs he wore during his long surgical days, his toothbrush, toothpaste, razor, a T-shirt and pajama bottoms, two suits, shirts, ties, his shiny leather loafers, a winter sweater, jeans, and snow boots all went into his travel bag.

He turned to her suddenly. “Come on, Joan. You’ve let me read a page here and there, but why can’t I read the Rare Baby stories from start to finish? I’ve got all these hours on planes and it would be great to read something other than medical journals and the newspaper.”

Three and a half years writing those stories and they still felt like a secret to Joan. She had all the audience she needed in Daniel and Fancy. She touched her belly and wondered if she would read them aloud to the new baby. There was always going to be a second child, and soon there would be.

She watched Martin’s mouth moving. He was still talking, inveigling her to let him read the work, but Joan was thinking of something else entirely, of how the news she was pregnant again had spurred a sort of silent trade-off: Martin no longer opened her study door without knocking, did not enter unless invited.

She tuned back in when his mouth clamped shut, his face clouded with hurt, and she thought she ought to give him the benefit of the doubt. She climbed off their bed, went into her study, gathered up five of the stories, and handed them over. She watched as he placed them neatly inside his briefcase.

A week later, back home, unpacking his bag, he pulled out her stories, all marked up, and her heart was once again beating too fast. She felt churlish, though, and remonstrated, when he pulled out a wrapped package and gave it to her. He had brought her a present, but when she opened it, there was a frightening device in her hand, antique and rusted, and Martin said, “That’s a scleral depressor from the early twentieth century. I found it in a store in Cologne. Isn’t it great?”

He turned it over in her hand. “You insert the tip between the globe and the orbit, the space occupied by the probe displaces the retina inward and creates an elevation. It helps locate and diagnose lesions that may otherwise go undetected, like retinal holes, tears, or vitreoretinal adhesions. It’s used to assess patients who present with complaints of flashers and floaters, or who are at risk for peripheral retinal anomalies, such as high myopes or those with a history of blunt trauma.”

He returned the depressor to its velvet-lined box. “I saw it and thought since I’m traveling to so many places, I should keep a lookout for these kinds of things, start a collection of old tools of the trade.”

She felt the ghosts of eyes touched by that tool, the coldness of the metal still singed her palm.

Then he said, “Come on. Let’s take Daniel for a walk.”

It was Sunday and they were Fancy-free. Daniel was in his room, on his bed, the novel she was reading to him—The Happy Island by Dawn Powell—on his lap, and he was pretending to read.

“Mommy, listen to me,” and he read, “Everyone who knew James knew of his Evalyn, and that a visit from the Inspector General could not cast a town into greater confusion,” and Joan was shocked. She recognized the sentence from the book, and he read on, “No one found her agreeable. Desperately James told stories about her to make her appear interesting, but she only emerged a more intolerable figure than before.”

She called out for Martin, and when he stood at Daniel’s door, she said, “He’s reading already! Whole sentences without sounding out the words. Just like I did, but I was older, five, when it happened.”

Martin kneeled before Daniel. “Are you reading now, my man?” and Daniel nodded and began telling his father about the bachelors of New York City, and Martin looked up at Joan.

When everyone was zipped into their winter coats and out the front door, Martin whispered, “Maybe we should make sure he reads age-appropriate books.” That wasn’t going to happen on Joan’s watch, but the battle could wait for another day.

They walked the wide streets of their development, the paving all complete, young trees bare-limbed in the cold, and were quiet for a while.

“So about your stories. I loved them all, but especially ‘Otis Bleu Sings.’ The way that baby could belt out an opera without any teeth in his mouth.”

Daniel twisted around in his stroller and called out, “Mommy already read me that story.”

They made rights and lefts through the neighborhood and all the while Martin was telling her his thoughts about the stories, the emotions he experienced while reading her work, then asking her questions. “How do you develop these characters? How does your brain hit upon these creations? What makes you think as you do? Are the stories based at all on Daniel, on the things he does? Are you imagining the new baby inside of you when you write?”

It was perhaps the hundredth time Martin quizzed her this way, wanting to dive into the depths of her mind, to know exactly how she put things into place, now asking specifically how she came up with the traits of her rare babies, their names, their family configurations, the outrageous things they did and said. This obsession he had to expose her processes, to aerate the pure elements of her work, he seemed to want her fully oxidized. She did not bask in his interest, as genuine and real as it was. Instead, she felt as if she were standing back at the abyss, and if he did not stop, if she could not stop him, she would fall into the darkness for good.

In the kitchen, after their walk, Joan told Martin he was in charge of dinner and closed herself up in her study. She sat at her desk and wished she were configured like other women who welcomed such keen attention, or at least like other writer-mothers who seemed to connect everything together, who handled with relish the confusion of it all, combining writing with motherhood, everything out in the open. There was a heroic disorder to their lives, but she could not abide it. This coalescing amalgamation of the disparate parts of her life—writer, wife, mother, pregnant woman again—was not what she had ever wanted. She had a baby, was going to have another, was writing about babies, had a husband who wanted to know everything about what their baby did in his absences, about how the baby inside was treating her, what her rare babies were up to, and how they had come to be. She was consumed by domesticity: the normality of her flesh-and-blood family juxtaposed against her manifested world, which was mystical, numinous, sometimes supernaturally odd, filled with erudite babies illuminating what others could not see.

She put her shaking hands on her typewriter, watched them settle, all the while feeling the impulse to walk out, to disappear, as she had considered doing when she told Martin she was pregnant the first time, their incongruent stances about the life she was carrying rocking her entirely, an earthquake upending the life she had anticipated for herself.

Her soul, she realized, was in disarray, and this second pregnancy was not helping. It was not at all like the first. She had morning sickness day and night. She was not miraculously glowing. A second baby would intensify the disorder she needed, somehow, to compartmentalize.

Over the next several days, she read through all fifty of her Rare Baby stories. They were beautiful, the writing strong and densely molded, but she did not want to publish such a collection, did not want to be yoked forever to these creatures who had been intended only to help her maneuver through that first vital metamorphosis.

She would not read them aloud to the new baby, when it finally arrived. She could not indulge in this exercise any longer. If she did, she would slip entirely away, become irreal, an outline when she was made more solidly than that. It was the first Joan Ashby, the realest Joan Ashby, the one who was neither wife nor mother, that she was in immediate danger of losing. She had to eliminate the concentric circles that dominated her life, otherwise she would not be able to carry on building the family they were building, would want only to cut the bonds that tied her down.

With Daniel, she had imagined herself as a character who would hang on to the love she had been given and love her unwanted baby, and she had done that exceedingly well. She would do it again when the new baby arrived. But before that happened, she needed to reframe her existence, fracture her life, bifurcate Joan Manning, wife and mother, from Joan Ashby, the writer, erect boundaries to prevent any accidental bleeding between the two.

Volkmann called only twice a year now to confirm Joan had received her royalty statements and checks. She no longer asked about Joan’s plans for her first novel, assumed Joan had ceased writing entirely, consumed with something like the joys of motherhood, and Joan allowed her that belief. The same was true with Annabelle Iger, who called every couple of months, saying, “Haven’t you had enough of this pastoral existence, all this mothering and wifedom? Aren’t you sick of love and diapers? Start writing again before it’s too late.” She and Iger talked of so many things, their editing days together, the men Iger was toying with, the plays Iger saw, the dance clubs Iger still frequented, but Joan never mentioned The Sympathetic Executioners or the Rare Baby stories to her either.

She was again at a critical juncture, and this time, she needed to maintain the divide, husband and children out in the real world, but on her own, the writing she did would be truly private, consecrated, known only to her. No more reading her work to Daniel and Fancy. The new baby’s arrival would eliminate her study, soon to be transformed into another nursery.

She watched the reddened sun pale and set, and she pictured a castle with a tower that soared into the sky, a moat that rendered it inviolable, an imaginary place where she would write for the next years, without Martin knowing. She would throw him off her scent, lie and tell him she was taking a break, void entirely his inquisitions. She did not want to hear him talking about her work, suggesting, pontificating, analyzing. On the walk, the names of her characters had been far too familiar in his mouth. He had her and Daniel and the child to come; that would have to be sufficient.

In that high tower, that place of pure self, she might find her way to that first novel, at last write a book worthy of the reputation she had developed. She only wanted what belonged to her—what she created, her characters, her people, those with whom she spent the clearest hours of her days. It was, she thought, the way to make that truest part of herself whole once again. And if she protected her most essential qualities, the core of Joan Ashby, she could continue to give the rest of her heart to Martin, to Daniel, to the baby inside.

She thought about Fancy. She could trust Fancy to keep her secret when Joan returned to her work, after the early months with the new one.

She looked at Martin’s father’s clock on her desk. It had taken only thirty minutes to arrive at her plans for the future. Joan opened the study door and headed toward the living room, where her family was gathered. She could hear the roll of dice, the movement of plastic pieces, Martin and Daniel laughing, accusing each other of cheating, and she was aware how those voices both attracted and repelled her.