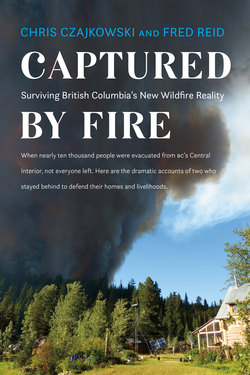

Читать книгу Captured by Fire - Chris Czajkowski - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Fire Smart

ОглавлениеChris

Kleena Kleene, July 9

Miriam, the friend I had picked up in Williams Lake, is no stranger to fires. She and her husband, Quincy, live near Lac La Ronge in northern Saskatchewan. The province used to fight fires diligently, but now enormous conflagrations are left to burn unless they directly threaten communities. “Our fires,” Miriam told me, “are not measured in hectares, but in square kilometres. Because of your hills,” she added, “you can see your fires and have a much better idea of where they are. In flat land, a plume of smoke might be two kilometres away or twenty kilometres—it is impossible to judge.”

Miriam and Quincy had built a cabin on an island in another lake, twelve kilometres from the nearest road. In June 2015, a friend of theirs was staying in the cabin, which had no phone or internet. Quincy and Miriam had checked out the fire maps and noted that one of a series of fires was less than ten kilometres from the cabin. Next thing, they received a tearful phone call from their friend, who had been evacuated to a hotel. She had been so scared that she had not dared fall asleep in case she did not wake up. The friend was safe, but the next day’s fire map showed the cabin had been engulfed. Miriam later wrote to me, “Our kayak, the cabin, the dog yard, the outhouse, the woodshed, the staircase down to the lake, the jack pines, the spruce trees, the Labrador tea, the grasses by the shore, the grouse sitting on her eggs, the little owl hunting mice, the lichen on the rock, the deep green moss—they were all left behind.

“I stare at the fire map, [our lake] surrounded by red, but I can’t believe what I see. And I couldn’t believe it until we stood on the scorched soil and sifted through the grey ashes of what used to be the dream of a wilderness home.”

Quincy maintains water bombers, and as their house had not been in the fire’s path, he had returned to work. His sister came and looked at the trees surrounding the house. “That one, that one and that one has to go,” she said.

“No!” Miriam replied. “The fire won’t come here.” But she kept staring at the tall balsam fir that was right behind her bedroom window. She tied a rope as high as she could on the tree, and with straps she tried to pull it away from the house. She knew that straps alone would not work well, but she didn’t have a come-along. She cut down the tree with her chainsaw. It hit the roof and tore a few shingles off. She trailered away brush load after brush load to a nearby gravel pit and cut down more trees. She knew it was futile, there were just too many, but she could not sit and do nothing. She kept working, pulling away grass and twigs close to the house. In the end the fire was diverted from their property and the house was saved.

After our hike on the dunes on July 8, Miriam stepped into her sister-in-law’s shoes and looked critically at my home. “The biggest problem,” she allowed, “is the open sides around the deck. Sparks can be blown underneath and ignite the dry sawdust and debris under there.” Some parts of the deck are over a metre off the ground. It is not a regular shape, but built in a bit of a curve. I did not have much in the way of materials suitable for walling it in at such short notice, but then I remembered the tarps. Over the years I had accumulated a large pile of woven, blue plastic tarps, now badly frayed and full of holes. I have lived so long without money and far from services that I have a very hard time throwing anything away. The tarps were in such bad condition, though, that every time I noticed them stuffed under the guest cabin I kept thinking I really must take them to the dump. Now I dragged them out and we stapled and nailed them to the deck, weighing down the skirts with rocks. By doubling them up we were able to obviate the worst of the holes.

The deck is surrounded by tarps to deflect wind-blown sparks. Photo by Chris Czajkowski.

The woodshed attached at the other end of the house was also open at the bottom, designed that way to allow air to circulate and dry any wet wood that might be stored in there. We swathed the lower regions with more tarps. Plastic isn’t going to stop a flame, but winds often gust furiously around the house and it might just be enough to deter a swirling spark. Miriam also carted away interesting roots I have collected to decorate the area. This is the sixth cabin I have built, but the only one in which heavy machinery was used. The silt dug out to make the basement was piled around the hole and, though a lot of what was left was removed, a wide circle of ground surrounding the house is as barren as the Sahara Desert. Year after year I have tried to grow something on it to stop the flying dust, but I don’t have enough water in my paltry well to nurture it, and little has survived. Hence roots and rocks for decoration. This sterile apron, however, now had a great advantage. There was a large open space free of vegetation around my home.

When I logged the small hill to create the building site, I had left a few pines for shade. I had taken down anything that had leaned toward the place where the house was going to be, partly because I knew how strong the local winds could blow, and partly because, should the unthinkable happen and I had to cut down trees to save the building, each could be toppled easily, with no danger to the faller. I didn’t want to annihilate my shade unnecessarily though, so I left these pines standing for the time being.

In the afternoon, we drove to downtown Kleena Kleene. A couple of other locals were parked beside the hayfields. The wind was not all that strong and, though the fires had spread a little, they still seemed unthreatening. One onlooker made a living operating heavy machinery, and he talked about trying to rustle up a water tank and some pumps, and a couple of skidders to build fireguards. The government frowns upon lay people taking problems such as fires into their own hands, but the government, as we well knew, was busy elsewhere. I would not be much use. I could use a chainsaw well enough, but bad knees meant it was difficult for me to scramble over rough country, and I had never driven heavy machinery.

Back home, I didn’t really think the situation too serious; even if the southwest wind got up, it would likely blow the fire away from me. Still, I figured that it wouldn’t hurt to start thinking about packing. I had been threatened by forest fires twice before, both times while I was still living at Nuk Tessli, the fly-in resort I had constructed nearly thirty years before. There, my only way out was by float plane. This vastly restricted the amount of things I could bring when evacuated, especially as, on both occasions, guests and volunteers took up plane space. And, each time, I had only about half an hour to pack.

Here, at my current home in Kleena Kleene, I had much greater vehicular capacity and the leisure to think about it. I was not sure that I was going to leave; still, it was better to get things together now. Items that I would not want to put into the van until the last minute would go on a list.

The first consideration was food. I have chemical sensitivities and would quickly become very run down on the canned and packaged “staples” found in any of the Chilcotin stores. Most of my food is purchased in bulk from far away, often by mail. Into plastic totes went organic rice; wild rice; oats; baking soda; raw, sulphite-free vinegar, etc. I left the fresh food in my basement for the time being as it was cool. I would have to leave room in the van for my two largish dogs and their paraphernalia, as well as some personal gear of my own, like a sleeping bag and clothes. The passenger seat was left free—it would hold my computers and cameras and all their accessories. (Who said laptops were portable?) Water jugs were placed ready to fill. Camping gear. Who knows, in a state of emergency, what one might need? An axe and chainsaw resided in the van permanently. A wave of pine bark beetle killed a lot of trees here twenty years ago, and they often blow down onto my four-kilometre driveway. The government has decommissioned the road (it used to be Highway 20), so the only people who maintain it are my neighbour Dillon and me. We plough it in the winter and cut it out every time there has been a blow.

The hiking trip that Miriam and I had planned was to have been at Nuk Tessli. Although I had sold the resort, I had agreed to guide clients for the owner that summer. Miriam and I had arranged to fly in early and hike for a few days on our own before the paying guests arrived. But road closures were now prevalent throughout BC. The clients that I was supposed to guide could not drive north. Also, there was no way that I was going to leave my place under these circumstances unless forced to, so the hiking trip was out. Miriam’s presence at this time was very useful, however. As well as the van, I own a small pickup truck and a trailer. Having an extra driver meant that I now had a lot more options of what to take. First the ATV went into the trailer. Then the snowplow, chains and ramp, followed by a second chainsaw. These things could all be replaced, but they amounted to quite a lot of money and I was not covered by fire insurance. Few people are around here. The population is scattered and we live far from a fire truck; there is no fire suppression service for hours in any direction. Any insurance, therefore, is expensive.

Because I live forty minutes away from a gas station, I keep cans of fuel handy. I tipped the contents into the vehicles’ tanks; empty cans would be far less flammable. Propane tanks would explode, whether they had gas in them or not, so all four were put into the trailer. Behind the seats in the pickup’s half cab went a few winter items—a couple of excellent wool blankets, my best winter boots, down coats, and a few out-of-print and irreplaceable plant reference books. A couple of thick sweaters. My favourite huge cast-iron frypan.

And what about all my personal stuff? Years of memorabilia from around the world; albums; art work, both mine and countless items from friends, either bought or traded; skull, fossil and shell collections—the copious attic was stuffed to the brim. I rescued a few documents like my birth certificate and journals, but as for the rest, I didn’t know where to start. The task seemed so overwhelming that in the end I packed none of it. Was there a sneaking feeling of relief in the back of my mind? Before I came to Canada in 1979, I had travelled for a decade round the world with a backpack. I’d had no possessions, very little money—but I was rich. Now I have property, vehicles, taxes and boxes of essentially useless stuff that I can’t really bear to throw away. It was as if it was no longer me who owned these possessions, but the possessions that owned me.

At some point during the day we lost the internet. I phoned a neighbour who received a signal from the same tower, but his signal was also down. Christoph and his wife, Corinne, own the Terra Nostra Guest Ranch on Clearwater Lake. Their resort is two kilometres southwest of my place (although it is a ten-kilometre drive to get there). His power was also out but he had a generator backup and was functioning with that. I hadn’t realized that BC Hydro had failed, for I have solar power. Christoph told me that a long string of power poles had burned near Lee’s Corner when the restaurant had been destroyed. I pictured the owners where I had last seen them in the temporary parking lot, waiting for the wind to drop so they could go home and guard their property. All they had left of their twenty-year Chilcotin life was their old pickup, a load of pop and chips, their little dog, and the clothes on their backs.

Still not a lot of wind, and we went to bed with a certain amount of reassurance. But how quickly things can change.