Читать книгу Captured by Fire - Chris Czajkowski - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Strikes

ОглавлениеChris

Kleena Kleene, July 7

It was early afternoon on a hot, rather dull day. I was sitting in a mechanic’s office in Williams Lake, British Columbia, while some work was being completed on my van. I was told that the van was OK for now, but it was going to need a brake job soon. That, however, could wait until the next time I came to town. I was not sure when that would be. Williams Lake, population 11,150, is the nearest place to my home that is big enough to boast a bank, a supermarket, traffic lights, a bus station, a full-time mechanic, and cell phone service. But my home is three and a half hours’ drive away.

Normally I would be out of town earlier, but that day I had to wait until 4:30 p.m. as a friend was arriving from Saskatchewan by bus. I was half dozing in the muggy heat and staring idly through the open door of the mechanic’s office. The shop is in a light industrial area; the buildings across the street are unattractive and utilitarian. Behind them climbs a steep-sided slope covered in coniferous forest.

Traffic on the road in front of the garage was busy and noisy, and it all but drowned out a few rumbles of thunder. Nothing particularly loud; most people never heard it. I was staring straight at the hill when the lightning struck. Three broad stabs of white light, one after the other. Bang. Bang. Bang. There was a wind up there, and within minutes black smoke was roiling into the heavens.

I have lived for nearly forty years in this dry, flammable country—long enough to have considerable experience with forest fires. My first instinct was to run. To get away from potentially panicky crowds. But Miriam’s bus wasn’t due for another couple of hours. It takes days to travel from Saskatchewan by bus and I could not abandon her.

People coming into the office were hyped up and talking.

“108 Mile is burning,” some said. (About an hour south of Williams Lake. The bus would be coming through there. Would it be delayed?) “It started there yesterday.” “Rumour has it that some kids were shooting at targets in a quarry.” “Doesn’t take much of a spark to set things off in these conditions.” “It is already out of control and the community is being evacuated.” People seemed oblivious to the smoke above their heads. The drama, for them, was elsewhere; they had not yet registered that it was also in their backyard.

The bus indeed was late. Smoke continued to boil from the hill east of the city. Finally, the Greyhound coach eased in behind the bus station, and there was Miriam, shouldering her backpack. She excitedly showed me pictures she had taken on her phone of the 108 Mile fire. I barely looked at them. I wanted to be gone.

“I just need to go to the supermarket,” she said. “I have everything I need for our backpacking trip except food.”

Hanging about to shop was the last thing I wanted to do. “I have plenty of suitable food at home,” I told her. “We need to get out of here.”

Fortunately our route took us directly away from the Williams Lake Fire. We would be heading west along Highway 20, the thin ribbon of road that runs all the way through the Chilcotin to Bella Coola. The highway first climbs over a ridge then drops down to the Fraser River. The following steep scarp, Sheep Hill, needs a couple of hairpin bends to gain elevation. As we climbed, we caught glimpses of the black smoke pluming up behind us; the fires must have coalesced as there was only one column now. It rolled along with the wind but was topped by a towering dense white mass of pyrocumulus. Pyrocumuli, or fire clouds, happen only when the burn is very hot. They are created by steam from a living forest and fierce heat from flames boosted by a high wind. The forces within are similar to those in thunderclouds, which is why they resemble their tight, cauliflower structure. Pyrocumuli over the wildest fires may even create their own lightning storms.

At the top of Sheep Hill, we were on the high, open country of the Chilcotin Plateau. At first there is little evidence of the mountains that hover just below the horizon, but they will draw closer as we head west. Once on the plateau, as very often happens when coming out of town, we drove beyond the overcast. The sky here was cloudless. The van thermometer was registering twenty-nine degrees Celsius.

We were now faced with a narrow, comparatively empty road. Due to our late start, the sun was already ahead of us. The sky was a blue so pale it was almost white. The land stretched wide on either side. But was that something on the horizon ahead of us? A smudge? A cloud? A fly splat on the liberally bespattered windshield? As we drove steadily on, we could see it was another fire. No: a series of fires, stretched in a line.

From the way the highway twisted, it was impossible to tell if these fires were going to be a problem. One moment we seemed to be pointing straight toward them—the next they would be off to the right. We drew closer and the smoke columns grew bigger. The sun glared through my dirty windshield, causing me to squint. Was that an obstruction ahead? Someone was parked in the middle of the road—a truck pulling a horse trailer. The driver, wearing a cowboy hat and a gunslinger moustache, was out of his vehicle, talking to the driver of a pickup coming the other way. “I know that guy,” I said. “He’s one of my neighbours.” I stepped onto the hot, windy road as he walked toward me.

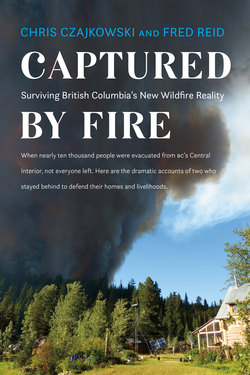

Four fires burn near Lee’s Corner on July 7. Photo by Chris Czajkowski.

“That’s it,” he said. “We’re not allowed through. We’ve got to go back. I have a daughter in Riske Creek—I guess I’ll head back there.”

I could not believe this. They could not be stopping us from going home. Surely there was a way through. We drove cautiously forward. We were about an hour out of Williams Lake and approaching a rest area perched on the top of a hill—two concrete outhouses, bear-proof litter bins, a couple of picnic tables. To the south a steep drop tumbles to the Chilcotin River, beyond which a rugged wall of rock and forest steeply rises. It is usually a pleasant spot to stop for a break.

Now several vehicles were parked sloppily around the outhouses, and below us rose a black tower of smoke from the southernmost of the string of fires. Everyone had bits of information. “All the other fires are north—that one’s south of the highway and the wind’s right behind it. That’s why they won’t let us through.” “It started at Yunesit’in (Stone Reserve).” “The wind’s been screaming down there all day.”

A cop was doing his best to turn us back. He was on his own and getting more and more frustrated. He jabbered angrily into his radio while driving to and fro, trying to round people up like a sheepdog attempting to control a bunch of excited goats. He would have been from the detachment at Alexis Creek half an hour west, one of only two RCMP stations along the whole of the Chilcotin.

We milled around getting photos, mostly ignoring the cop. Although the bottom of the hill was invisible from our viewpoint, I knew that the junction with the Nemiah Road lay there. It ran south for several hours, dead-ending at Xeni Gwet’in (Nemiah) and Chilko Lake.

At the junction, there was a restaurant. Although the current building was not the first to occupy that site, one had existed there for many years. In the unadorned dirt yard reposed a gas pump, and four small, very basic frame cabins that did duty as a motel. The location was known as Lee’s Corner, which was part of Hanceville, population three.

The place had already been ramshackle when I had first come across it thirty-five years ago, and though owners had come and gone since, not much had changed. Half a set of horse hames worked as a handle for the heavy door, and a clattery cowbell announced entry. Inside, despite the roaring, rattling fan, the place reeked of years of ancient grease. A new flat-screen TV blared and the coffee was execrable—but the baking was superb. I can no longer eat wheat or sugar without regretting it, but was always tempted by what had to be the best carrot cake in the world. I often complimented the baker—bent over with arthritis, she was unable to stand upright—and she shyly acknowledged my praise. “You know,” she confessed one time, “I hate making it.”

I would also stop there for a caffeine boost to cope with the last slog homeward after a long day in town, and if I had passengers, we would get something to eat. It was the only place along our journey that could be relied upon to serve meals late in the afternoon. Miriam and I had looked forward to having a break there.

Still unable to believe that we wouldn’t be able to go home, or even get as far as Lee’s Corner, we reluctantly turned back. “There’s a field about twenty kilometres east where you can wait,” we were told. I did not know who had arranged for the gate to be open but a dozen assorted vehicles were spread haphazardly over a small, stony field. The land was desperately dry; what little grazing had existed had been mashed to dust under the tires. Some people were strangers, but others I knew. Friday is town day for many of my neighbours. One pickup belonged to the owners of the restaurant so near but so unutterably out of reach. They had been to town to get supplies. Their load consisted exclusively of pop and chips. “Sorry I don’t have any carrot cake,” said the baker sadly, trying to smile. They were expecting the wind to die, as it very often did when the sun went down, so they would be able to go home. The restaurant was licensed, and the owners were worried about looters.

No one believed this would be anything more than an inconvenience. There were fires every year on the Chilcotin. True, the dryness was on the extreme side this year, but drought and thirty-degree temperatures in July were not unusual. A month previously I had set off on a road trip to the Yukon. Green was all I saw on that trip, for I had been dogged by deluges of rain and snow and hail. But on my return to the Chilcotin only three weeks later, my jaw dropped.

The land was as crisp and brown as it would normally be after the heavier frosts of September. The sparse weeds and grass amid the stunted forest were brittle as cornflakes, disintegrating into dust as I walked on them. Fenced areas were bared to the earth, the stalks probably destroyed by animals’ feet as much as their hungry mouths. Beyond the pastures is open range. Open range in this country means forest. Huge parcels of pine and Douglas fir hold pockets of grazing around ponds and sloughs, on old burned areas, and in clear-cuts. The cows are put out there at the end of May and rounded up in dribs and drabs through November.

What had caused the rapid drought of 2017? The summer of 2016 had been unusually wet; the subsequent winter’s snow cover not particularly heavy, but fairly average for the area. No one I knew had ever seen such a short green season, or such a rapid change to brown.

The restaurant owners had their little lapdog with them; their half-wild white tomcat would be sleeping off the heat somewhere near home. Their only close neighbour, forced to evacuate with no real warning, sat in his pickup, scowling. The hot wind coursed through the open windows of his cab. Two large dogs of indeterminate breed were sprawled across his lap; he had been unable to find his third.

My nearest neighbour, Dillon—who lives four kilometres farther along my bush road—was also in the field. He and his soon-to-be wife, Tamara, were heading west, but only as far as Tsi Del Del (Redstone Reserve), where Tamara’s mother owned the store. Their plan was to stay the night and gas up before they went home the following day.

Other people in that stony field were strangers, but we talked, all a bit bewildered. Some had families and livestock on the Nemiah Road. No one wanted to be in the field but we didn’t know what to do. Maybe the wind would die and we would be allowed through. Someone said there was a series of logging roads going north; they would detour us around the fires. But rolling walls of black smoke lay in that direction. It looked as though we might run directly into the flames if we went that way.

A truck towing a trailer pulled into the field. The driver worked for Forestry. He confirmed that there was indeed a way round and he knew where to go. “It’s pretty rough,” he said, eyeing my van. “And I won’t be going slow, so it will be very dusty. It’ll take about an hour and we’ll end up at the Forestry building at Alexis Creek.” I thanked my lucky stars that I had splurged on truck-quality tires for the vehicle that spring. My four-kilometre driveway is pretty rough, and prior to that, flats had been common. I ran and told Dillon. He hoped he had enough gas. He unearthed a half-empty can from the jumble of chainsaws and tools in the back of his truck and topped up his tank.

Off we went. Instantly we were plunged into a rooster tail of dust and could see almost nothing either ahead or behind. I lost sight of the trailer but kept following the dust cloud. Occasionally the road forked—I followed the direction in which the dust cloud hung and hoped the wind hadn’t moved it. I had no idea if Dillon was behind us. We met other vehicles roaring the other way, all rushing to get around the fire before someone got smart and closed this route as well. The road was so narrow we were often forced to the very edge where the gravel was coarse and piled into a little ridge.

The dust grew darker; it was now mixed with smoke. Cows wandered in forlorn groups. Miriam was taking pictures. “I see flames,” she kept saying, pointing to both sides of the road. (They were only small flames.) We hurtled on. A guy coming the other way flagged us down and told us to watch out for a cattle guard ahead—one man already had a flat tire from it. He must have hit it wrong, for it wasn’t a problem for us, crossing in the middle and going slowly.

At a major fork, our guide was waiting for us. We stopped for a while to see whether Dillon was behind us, but there was no sign of him. I hoped he didn’t have a flat. He and Tamara were both experienced in the bush—I knew they could look after themselves, and the presence of other drivers meant someone would stop if they needed help. Our guide was anxious to move.

The smoke was now high in the sky, like a lid above our heads. But the flames were behind us and the scruffy, brittle forest ahead was clear in the hot, late sun. Now, however, the road was even rougher. On we flew, following the dust plume, rocks the size of tennis balls sliding under our wheels. And then suddenly, down a hill, there was the Forestry building and the tiny town of Alexis Creek, seemingly deserted like a city abandoned in a disaster, which I guess it pretty much was. Two hours after we were first turned round, we were back on Highway 20. We were only twenty kilometres from the aggressive column of smoke at Lee’s Corner, but we were on the right side of the fire. The sky was clear, and now it was calm. Not because it was later in the day, but because the fire wind wasn’t blowing here. This country is famous for the contrast between gales that roar wildly through mountain passes and dead calm areas elsewhere. It was now about 8:00 p.m.—still full daylight at this time of year. Two hours to go. We stopped in at the Tsi Del Del store to let Tamara’s mother know that she and Dillon were hopefully behind us, then continued steadily along the empty highway. Logging trucks had been forced to quit hauling just the day before. Logging always has to stop when the fire hazard is high: too much risk of iron hitting rock and causing sparks. Logging trucks constitute the majority of traffic this far west, and without them the road was eerily quiet.

Twilight suffused the land about the time we drew close to the mountains. It was cool enough to close the van windows. The nights never get truly dark at this time of year and only the brightest stars were visible. Our headlights cut a lonely swath through the dimness.

Past Tatla Lake—forty minutes to go. Not far west, the road bends sharply to cross a river. As I slowed for the turn, I suddenly smelled it. Smoke. Oh! No! It was like a blow to the stomach. I could see no sign of it—the dark ridges against the summer night sky seemed clear and sharp. The river captured the light and gleamed faintly. But the smell was unmistakable—not a chimney fire or campfire (neither would have been present in that unpopulated spot in any case) but the distinctive reek of a burning living forest.

It was another ten minutes before we saw them. Just two or three small fires, gentle and seemingly innocuous; one would hardly notice them if it wasn’t for the darkness. They were high on a forested ridge behind downtown Kleena Kleene.

Downtown Kleena Kleene used to boast a ranch house, a mechanic’s shop, a store and a school, but no one lives there now. The only thing of note is a state-of-the-art sprinkler system, recently installed to irrigate several hectares of prime hayfields. Tame hay is a rare species in the Chilcotin. Most of the country is scrubby forest, either rocky or silty depending on what the glaciers dumped during the last ice age, pockmarked with bogs that provide coarse “wild hay” composed mostly of weeds and sedges. The sprinkler system was idle and tucked against the highway fence, no doubt pulled off the fields in preparation for haying.

To our amazement we could see that the road here was wet. It had rained. The fires burned quietly but steadily. Small red candles in the night. We drove on; I stopped at the old cabin that does duty as a post office to pick up mail from the ancient shabby green boxes. Mail comes to the Chilcotin by truck, three days a week. I had no way of knowing that I would not see that post office again for nearly a month. A few more kilometres and we turned off the highway onto the bush road that Dillon and I share. We marvelled at the puddles on it and the weird way that the van’s headlights reflected off them into the scruffy trees. I had not seen water on the road since breakup in May. The summer dark was soft and cool and calm. Although the drive had been twice as long, the fire was probably five kilometres away from my house as the crow flies. There was no sign of it from my yard.