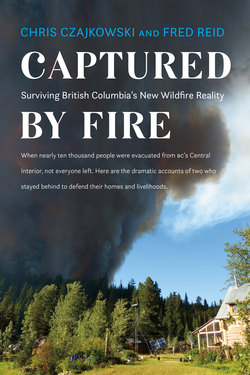

Читать книгу Captured by Fire - Chris Czajkowski - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preparing for the Fire

ОглавлениеFred

Precipice, July 10–14

I turned my back on the fire in some form of denial, angry with myself that we were so unprepared for such an event, living as we were deep in a forest so dependent on a cycle of fire. Evidence of past burns was all around us. Evidence that we had ignored. The densely packed pine we hiked through on outings to Crazy George Lake, a small lake we named after a hermit who had lived in the bush near our valley in the seventies, was regrowth from a fire seventy years ago. The charred remains of logs along the ridges of our hikes, and the darkened bark of the mighty Douglas fir that grow at the very edge of our meadows, stared us in the face at every turn. How could we have ignored these warnings?

In the afternoon Arlen flew in with two Initial Attack crews (IAs) of three firefighters each, a handful of sprinklers bought at the hardware store in Bella Coola, and some two-centimetre hoses that would be connected to the mainline. Arlen explained that they were not trained for structural protection but felt it was necessary to do whatever they could, because if the winds picked up, the fire could reach us in a day. The Bella Coola Forestry field office had limited resources on hand but expected a Canadian Air Force plane to fly into Bella Coola at any time with a container of structural protection equipment. I followed Arlen around like a puppy dog, anxious to learn what I could about how to protect our place. He asked what buildings were of highest priority. Monika and I accepted that some would be lost (the sauna and lumber shed had wooden roofs and the greenhouse was covered in plastic). We decided the house and the pool room should receive the protection of sprinklers. We would try to protect the barn with our own hoses and nozzles, drawing water from a standpipe near the barn. By early afternoon the IA crews had added three sprinklers to our system (two on the house and one on the roof of the pool room) then left for the Taylor Ranch to place their remaining five sprinklers. This was grossly inadequate for all the buildings, but we were very grateful that they showed such concern for us and were willing to do whatever they could.

Arlen pointed out that falling embers were the biggest danger. They could find their way into cracks and onto piles of fuel in the form of dried wood, grass or other combustibles. After Arlen left, Monika, Hoss and I began removing firewood from our sheds by the house and the greenhouse, dumping the piles onto the green meadow at a distance from the buildings.

Everyone had much more fire experience than we did. Hoss told of a ride out of the mountains driving his pack horses ahead of a wildfire with the embers falling around him. David J was steeped in firefighting, as if weaned on it very early in the forests of British Columbia. And there was Arlen, so nonchalant about the fire, acknowledging that “it would burn” but doing all he could to protect us and our buildings.

The Precipice Fire smouldered in the distance but was not growing quickly on this day. By late afternoon Mark flew in and told us the fire had increased only from 650 hectares to 680 hectares—but it was now only three and a half kilometres from us, on a point jutting out along the north slopes of the Hotnarko Canyon. He again urged us to leave. We were too tired to consider leaving and too busy to take pictures—the western horizon was a featureless wall of smoke in any case.

Tuesday, July 11, was one of the darkest days of the fire. David J phoned in the morning. The Kleena Kleene Fire was raging and they needed all the resources they could muster to fight it. The folks of Anahim Lake were concerned because new fires were breaking out and the existing ones were expanding rapidly. Although it was thirty kilometres away, Anahim Lake was directly downwind from the Precipice Fire. People felt that the hoses, sprinklers and pumps that had been lent to us were needed to protect their own homes and ranches. David J was coming in to pick up his pressure pump. I was stunned by this turn of events. We were the closest to the fire and directly in the path of its most likely onslaught. It had to come through us to get to Anahim Lake. If it could be stopped at our place, Anahim Lake would be safe. We were the first line of defence and in the most need. How could David J consider such a thing?

Monika was in tears with the news. She phoned Lee immediately. I walked to the pump uttering a continuous string of expletives. Hoss stumbled after me.

I shouted, “If I had a gun I would go to the gate and not allow him on the property.” Then I turned to Hoss, a friend of both David J and me, and said more softly, filled with dejection, “But I don’t have a gun and I probably wouldn’t do that anyway. It is his pump after all.”

Hoss and I stood next to the pump as Monika approached. “Lee phoned back. He talked with David. He will not be taking the pump.”

But David’s call had added to my stress and mixed emotions about those helping us. My confusion and numbness would continue in the following days as we scrambled to improve our protection and waited for the fire to come.

For the second straight day the fire was quiet. We could hardly see evidence of it—only small plumes of smoke from time to time. On these days my fear lessened, but we were warned that it was still out there and that it could not be stopped. Mark and Arlen flew in daily after circling and assessing the fire’s activity and growth. With each return of the helicopter we would drop whatever we were doing and walk to the edge of the propeller’s downdraft. Arlen, always smiling: “It’s just bubbling away.” Mark, confident and concerned, continued telling us that we were under evacuation order and that we should leave, assuring us that they could protect the buildings. We appreciated the constant updates, eager to learn all we could of the fire’s movement and proximity to us.

Our gratitude and confidence in the Coastal Division of the BC Wildfire Service was being cemented. They were putting together an Incident Command (IC) to fight the fire but were competing for resources within the BC Wildfire Service because of the other fires raging in the province. Many ICs are groups of professionals that move as a unit. With VA0778, Mark, the incident commander, and Kerry from the Bella Coola field office were drawing resource people from within the Wildfire Service to form the IC. The number of people in the IC and their responsibilities can and often did vary. Basically it consisted of an operations chief responsible for ground and air activities (Arlen); logistics personnel (those who had to locate and obtain resources for fighting the fire: this included everything from chainsaw fuel to helicopters to crews of firefighters to bulldozers); a plans chief; a financial officer; and an information officer. In this IC, the desperate search for resources necessitated four people working in logistics.

Four days into the fire, Mark had still been unable to acquire the resources he needed. He wanted helicopters to bucket the fire and firefighters to battle it on the ground. One of the problems was that VA0778 had started in the centre of Tweedsmuir Provincial Park. We understood that it was policy not to fight fires in provincial parks and ours was considered a remote area. We were surprised that they were doing anything for us. Mark and Arlen assured us that they would fight the fire and improve our structural protection; it was just a matter of when the resources would arrive.

The lack of strong winds was giving us time. The fire was moving on two fronts. In the Atnarko Trench at the bottom end, close to the strikes, it was creeping both north and south, threatening a walking bridge across the river. (The bridge had recently been rebuilt after the previous one had been destroyed in the 2010 flood.) It was also heading up the Hotnarko Canyon toward us. We remained lucky that it stayed on the ground, finding its way around rock bluffs. It was constantly burning and advancing, but it was unable to access the tree crowns and move rapidly. Our concern increased when the fire, which had so far been active only on the north slopes of the Hotnarko Canyon, jumped the river. Now we were threatened along both sides of our narrow valley. Mark was trying to determine where his resources could best be deployed—once he had them.

The structural protection at our place and the Taylor Ranch was still grossly inadequate. The cheap garden sprinklers that Arlen had brought to our place—they were all he had been able to get—were already beginning to malfunction. At the Taylor Ranch, the five sprinklers were on a single line serviced by a small backpack Forestry pump. There was not enough pressure to drive all the sprinklers at the same time. The Taylors’ house was some distance away from the ranch buildings and was not close to a good water supply. A couple of sprinklers provided by Troy had been set up there. The house at the top of the valley where Jade and Ryan were living, known by the firefighters as the Red Roof House, and the Mecham Cabin had no protection at all. Caleb asked for help from other friends in Anahim Lake. Lee and the owners of the Red Roof House bought two smaller pressure pumps each and more water hoses. It was a wonder that they found any. Pumps in British Columbia were rapidly being bought up and the price of them was rising. The pumps were flown to the Anahim Lake Airport and ferried down by the volunteers. Others also brought pumps and hoses. I took a spare hose from our place to the Taylor Ranch, where they were jerry-rigging hoses to fit pumps, and nozzles to fit hoses. David J, still committed to us, was in Anahim Lake installing a large tank onto his forwarder to provide water to protect both the Taylors’ and the Red Roof House.

There was news of imminent relief from our trepidation when Mark flew in with Gord from Comox Fire Rescue. They asked to look around to assess our structural protection. The roller coaster of emotion I had been on since the beginning of the fire had brought me to near collapse. I did not bother to accompany them, and instead waited aimlessly for their return to the helicopter. They explained that there was still some difficulty getting the supplies into Bella Coola but assured us that they would have things worked out and they would come into the Precipice by truck the next day.

Our lives were turned inside out. We had to undo much of our work of late spring. We placed plywood over the open entrances to two sheds and moved loose hay away from all outbuildings—raking the ground to bare soil. We removed wood from our woodsheds. We moved equipment, vehicles and fuel containers out of the buildings and onto the meadow where they had less chance of being consumed. Piles of fire-hazard debris were randomly scattered over our once tidy meadows. The meadows would normally be drying out at this time to encourage second growth, but we had to leave the irrigation ditches open to provide water for the pumps.

The barn remained our biggest concern. We had been happy to have baled the first crop of hay early and to have it nicely stored in the loft, but now it presented our biggest fire hazard. The loft was consciously well ventilated by a slab cladding with many open spaces. These spaces were an invitation for hot embers. We did not want to remove all our hard-gotten hay but we did not want to lose the barn either. We elected to leave the hay, and Hoss and I set to work stapling tarps and plastic over the gable ends to cover the openings. As we neared the apex of the north end, a barn swallow flew out of a large gap. We would have to be very unlucky for the fire to find this spot—it would have to arrive from the opposite direction—and we left the opening so the swallows could continue to feed their fledglings.

We had been dazed since the beginning of this ordeal. Our brains were in a fog thicker than any smoke we would ever experience from the fire itself. In fact, on some days you would not even know that the fire was out there. We were on a steep learning curve. With legs of rubber we climbed the curve, unsure of where the crest of the hill would be.

As topsy-turvy as our routine became, our emotions were more so. We felt gratitude for all that was done for us, but I was also confused. I was still very shaken by the fact that David J had wanted to take the pressure pump even though he continued to work diligently at the Taylor Ranch and Red Roof House. I felt inadequate, overwhelmed by all the decisions that now faced me and the various opinions regarding evacuation, structural protection and forest firefighting. I just wanted to be left alone rather than be confronted by conflicting ideas and loyalties. Monika was the opposite. She embraced all the help. She smiled from ear to ear when she heard a helicopter coming in. She rushed out to the edge of the meadow just beyond the swirling grass, anxious for any news. I dragged a little behind but usually joined her by the time the propellers stopped.

Our next helicopter brought bad news. There had been problems flying the structural protection equipment into Bella Coola. The truck and container were too big to fit into the military transport plane that had been designated for the job. Everything would be delayed for another day. However, they had contracted Rob, a seasoned pilot with a mid-sized helicopter, to begin bucketing the fire. Monika and I had been reluctant to take pictures of the helicopter Mark and Arlen had flown in on. We felt that doing so would be intrusive to their work that we were so grateful for (and a bit embarrassed about). We watched as Rob prepared to bucket the fire. He seemed a bit standoffish, barely pausing to wave as he rushed around the helicopter unloading line, bucket, net and retardant, then leaving quickly with bucket in tow. He began drawing water from a lake less then a kilometre from the blaze, making swift one-and-a-half-minute returns to the fire’s front.

Many friends had heard of the fires through Chris’s blog or Pat Taylor’s and others’ Facebook posts. We had maintained a Facebook page for some years but had in fact rarely put anything on it. On July 12, I wrote: “I guess it’s time we said something. No pictures though. It is tough to send a picture of a wall of smoke. That is all there has been for three days now. Each morning we look into that wall trying to determine where the monster is—no flames, just more smoke. But it stays away from us. The air quality is actually quite good for most of the day.

“We have had lots of support. Friends from Anahim Lake have supplied equipment and well wishes, and the Wildfire Service drops in twice a day to give us a report and provide us with infrastructure to protect what we can.

“Each day that the fire has stalled has given more time to prepare. We have more worry than fear. When I asked Monika how she was feeling she responded, ‘I feel like I would just before a big exam.’ It rang so true. That sinking feeling low in the stomach right down to the intestines. Have I studied enough? (Have we done all we can to protect the buildings?) What questions will be asked? (From which direction will the fire approach?) We are hoping that classes will be cancelled.”

On Thursday, July 13, almost a week after we reported the fire, the Comox Fire Rescue team drove down our bumpy tote road and gave our structural protection a major overhaul. They replaced some of the sprinklers that Arlen had installed. They made loops of hoses around the house and greenhouse. Gord explained that sprinklers placed within a circuit would have equal water pressure. The house and greenhouse now each had five sprinklers protecting them. More were added to the chicken house, snow machine shed and Monika’s cabin, an exquisite little two-storey structure next to a channel of the river we call the creek that runs through our property. It has two rooms on the lower floor and an upstairs bedroom over one half. Monika had done most of the construction herself. It had taken her over three years to complete and we were very proud of it.

Monika sheepishly showed Gord how we had put plastic on the barn’s gable ends. Gord smiled and showed her the roll of plastic inside their pickup. “That is exactly what this is for. You have done a good job.”

When they placed a powerful Wajax pump next to David’s I felt a pang of mixed emotions—we had gone from the possibility of having no pump to having a backup. The pumps were set side by side. With a simple transfer of the mainline we could use either one.

I liked David’s: it had a Honda four-stroke engine that I was familiar with—they do not require a mix of gas and oil and are very easy to start. Its drawback was that it did not have enough power to drive all the sprinklers at once. This limitation had been overcome by running half the system at a time. The powerful Wajax could easily power the whole system but we were warned that it was not easy to start and had to be fed a mix of oil and gas drawn from two gas cans. One of the structural protection people began dramatically pulling on the cord and fiddling with the choke and throttle, but was unable to get it going. A second crew member gave it a try—he squeezed a suction bulb situated between the gas cans and the pump in addition to pulling the cord and fiddling with throttle and choke. The engine sputtered but did not start. A third person finally brought it to life. David’s pump looked more desirable to me with each passing minute.

Our place became a hub of activity with two helicopters flying in and out and structural protection people buzzing around. I began to embrace this new energy. By late afternoon the Comox crew left, promising to come back the next day to work on the Taylor Ranch and the Red Roof House.

Fred works with the two pumps. David J’s is on the left, the Wajax on the right. Drawing by Chris Czajkowski, from a photo by Monika Schoene.

After they left, the west wind picked up, clearing some of the smoke from our valley and blowing it toward Anahim Lake. At times I felt that my gloom was related to the amount of smoke as much as anything else. The afternoon was clear and hot. But VA0778 never let us enjoy a sunny afternoon for very long. There were soon dramatic plumes of smoke across the western horizon. Rob constantly dumped water by helicopter in front of the part of the fire closest to us, keeping it cool and slowing it down. As Arlen would say, “We want it to bubble but not to boil.” The plumes of an afternoon run were frightening but they were also beautiful—greys and blacks were mixed with yellow and deep orange as the sun descended behind them. By evening the fire—and the smoke—settled, resting for the night. We ran the sprinklers for half an hour to make sure I could start the Wajax—assurance so we would sleep better.