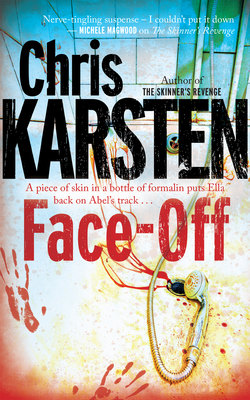

Читать книгу Face-Off - Chris Karsten - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5.

The first impulse of a man on the run, Abel thought, was to create the greatest possible distance between himself and his pursuers in the shortest possible time. Fight or flight: that was how the primitive brain of man and beast worked. Even if your pursuer is just a young woman, attractive and slim, weighing no more than fifty-five kilograms (at a guess).

Abel had chosen a different option. He’d lay low, in the heart of the hunting ground, as it were, to allow his physical wounds and those of his bewildered spirit to heal. He needed a clear head for this hunting season, where he was the prey. He had to anticipate his pursuer’s ruses, with three countermoves at the ready like a good chess player.

His recuperation had taken six weeks, but he had not been idle during his confinement. The damage had been to his body and his spirit, not his mind, which was still sharp: he knew how to determine the positions and culminations of constellations, the magnitudes and declinations of stars. He knew Ptolemy’s mathematical and astronomical second-century treatises, as analysed and explained by later texts: the Almagest, about the movements of cosmic bodies; the Tetrabiblos, about the cycles of those heavenly bodies’ meteorological influences on the atmosphere; the Phaseis, Ptolemeus’ star calendar, about the appearance and disappearance of fixed stars during a solar year.

Abel was also an expert on authentic ethnic masks. He knew the symbolism and history of the masks of even the most obscure African tribes, could describe off the top of his head the masks worn by the Bwa and Nuna of Burkina Faso to exorcise evil spirits, those worn by the Dogon and Zackana of Mali in dance rituals to communicate with the spirits of the ancestors, the war masks of the Grebo of the Ivory Coast and the Ashanti of Ghana, the death masks of the Balubri and the nomadic Fulani of Guinea, the harvest festival masks of the Kwele of Cameroon, the masks the Lulua and Teke of the Congo dedicated to the soil and the animals of Africa.

Abel knew music too: specifically and exclusively Paganini’s violin compositions. All other music was painful to his ears, made him sweat and tremble. The cacophony of pop and rock, folk and jazz confused his spirit. He knew the M.S. numbers, names and keys (and opus numbers, where available) as published in Moretti and Sorrento’s thematic catalogue of all Niccolò Paganini’s compositions, even those the violin virtuoso composed for guitar. Abel’s firm favourite was the 24 Caprices, Op. 1, M.S. 25, renditions by various violinists, because Abel was particular about the artists who attempted the master’s compositions.

He also knew that a heavenly body had been named after the great composer: in 1978, Nikolay Stepanovich Chernykh, looking through a ZTSH telescope at the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory near Nauchny, had discovered asteroid 2859 and named it after Paganini.

Yes, he was a connoisseur of African masks, Paganini and cosmology – and was, in fact, in the process of compiling a series of volumes of his personal astronomical observations and discoveries.

He believed he had an astute, orderly brain, yet he was unable to comprehend why certain young women, blessed with beautiful skin, were so reluctant to donate parts of it to him, as small as A5 in size; skins preferably adorned with tattoos of astronomical significance.

He needed those skins for the covers of ten volumes of his Cosmic Travels, and he already had two. But it was because of those first two reluctant donors that he was now a fugitive, because they had refused to cooperate and had forced him to harvest their skins against their will. He still needed eight more donors. He also needed another special woman to give him the greatest of gifts: a new face, his ultimate wish. For this face, as for the skins, he had strict requirements. The face had to be beautiful, the complexion flawless. Not just beautiful on the outside either: the donor had to be pure of body and soul. That was not negotiable; he would not accept the face of a slut. Since his childhood his mother had bombarded him with Bible verses that warned him against such women.

Ironically, while avoiding his hunters he had shared his hideaway with women who were guilty of Old Testament acts of iniquity: women who seduced men with embellishments to their bodies, and vulgar tattoos, and whose lapdogs and kitty cats wore coloured ribbons in their perfumed fur.

Oh, how he would have liked to have harvested a few of those pelts to hone his flaying technique: the skin of a Pekingese, a Toy Pom, a chihuahua, a dwarf poodle, even a shih-tzu, which would barely render an A5-sized pelt. He’d avoided skinning dogs, though, because he’d once had two pit bulls himself.

The cat was different, sitting in front of his door, mewing at night so he couldn’t sleep. Whenever he opened the door – to go and buy medicine, or a Paganini CD, or food – the cat had slipped in. Mitzi, the woman had called her. He knew the woman’s name too and had considered practising on Jewel, harvesting the Gothic cross at the nape of her neck and the snake on her thigh, the one that was visible under her short skirt when she walked along the passages, with her cries for Mitzi piercing his ears like needles.

He’d decided to practise on her cat.

* * *

After leaving the Sleep Inn, his final journey to freedom had taken a lifetime, or so it seemed. He’d considered all options carefully and decided to travel by train again. South African airports were too dangerous, despite the authorities’ ignorance of his alternative identity: Bartholomeu Lomas, citizen of Portugal. The problem wouldn’t necessarily occur on leaving the country, he’d thought, but on entering a new country.

The journey by train to Lusaka in Zambia was not without incident, but once there he had reserved a flight under the name of Lomas to Nairobi, Kenya, with a transit connection on a Czech Airlines CˇSA flight to Prague.

At Prague’s Ruzyneˇ airport he’d presented another passport, this one in the name of Dr August Lippens, citizen of Belgium: back in Bujumbura, his friend Jules Daagari’s fabricateur had modified the Lippens passport so that it displayed Abel’s own photograph, the way he looked now, the result of a botched “weekend facelift”.

He’d spent the day in Prague, visiting the fifteenth-century astronomical clock in the Old Town Square, located between Wenceslas Square and the Charles Bridge across the Vltava. He was interested in this astrolabe, which medieval astronomers had used to determine the position of the moon, the planets and even the stars. Of course, he knew that Ptolemy had used an astrolabe much earlier, for the astronomical observations recorded in his Tetrabiblos.

That night he’d caught the Copernicus night train to Amsterdam from the station near Wenceslas Square. During the fourteen-hour journey he’d rested. From an Internet café at the station in Amsterdam he’d sent an e-mail to his friend Ignaz Bouts, informing him of his arrival time in Bruges, his final destination.

The end of a long journey; the beginning of his new life.