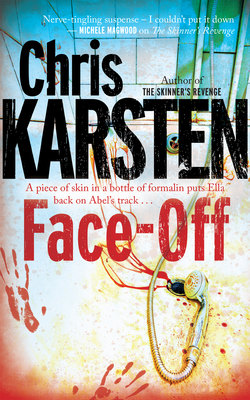

Читать книгу Face-Off - Chris Karsten - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

6.

ОглавлениеThree hours per day, that was the only private time Ella allowed herself. Well, not per day, strictly speaking, because it was almost dark by the time she went jogging at Alberts Farm, and it was still dark when she left in the mornings to go to the gym with her colleague, young Stallie. But it was the only time she could set aside for personal pleasure. And God knows there was little enough pleasure in her life, personal or otherwise.

Finished with the gym, she was always at the office by daybreak, or knocking on doors in search of witnesses and evidence in a murder investigation. At six in the evening she would drive home, put on her comfortable old Nike trainers, black spandex pants and a T-shirt. The sun had set by the time she was back, had taken a shower, had a bite to eat, pulled on her old jeans and driven off for her harp lessons with Suki Wolski three times per week. When there weren’t lessons, she practised in her living room on the second-hand lever harp Suki had lent her. From this old 36-string Troubadour she would progress to an orchestral pedal harp, Suki said. But she was to practise every evening, Suki had told her, no excuses. Like Harpo Marx, who even took his harp – albeit the smaller folk harp – to the toilet, where he played “I Got Rhythm” on the loo.

“Was Harpo constipated?” Ella had asked.

“Well,” Suki had said, “that’s why he was such a good harpist – he used every minute of his free time to practise. His music came from his heart and his soul, not from his fingers.”

“Just don’t expect me to play ‘Bolero’ on the toilet,” Ella had replied.

She’d positioned the borrowed Troubadour in front of the television in the sitting room; the bathroom was too poky anyway, laundry all over the place.

An hour for jogging, an hour at the gym, an hour for the harp – the sum total of her free time. And she’d just sat down behind the Troubadour, her hands on either side of the strings, little fingers held aloft, when her cellphone rang. Suki had said: “You might as well have your little fingers amputated. You don’t need them for the harp. If a little finger tries to find a string, it contorts the entire hand. Forget about your little fingers; keep them out of the way.”

Ella wanted to ignore the ringtone, R. Kelly’s “I Believe I Can Fly”, but she’d already seen the caller ID.

“Evening, Colonel.”

You never ignored the boss; he got irritated if his call wasn’t answered by the second ring, day or night.

“What are you doing? Are you busy? If you’re free, phone Sgt. Mfundisi, Kensington uniform branch. Could be something, could be nothing, but phone him.”

“Kensington? That’s outside our jurisdiction, Colonel. Don’t they fall under East Rand Murder and Robbery?”

“It’s not a murder.” A short pause, just a second, then he said, his voice rasping: “Well, it’s not a person. Looks like a cat’s been slaughtered.”

“A cat?”

“In a hotel room.”

“What about the SPCA, Colonel? Aren’t cats their . . . jurisdiction?”

Was it a crime to slaughter a cat? If the cat had been abused, she supposed it was, but hardly a case for Murder and Robbery.

“There was a jam jar on the nightstand in a hotel room. Not filled with jam, but with formalin and a skin . . . hair removed and tanned. The forensic lab identified it and informed Sgt. Mfundisi late this afternoon that it belonged to Felis catus.”

“A skinned cat? So, has a crime been committed?”

“Sgt. Mfundisi says he’s a bit confused as to whether it’s a crime to skin a cat and tan its hide. The bathroom is still cordoned off, but the hotel owner is putting pressure on him. Says if no crime has been committed, he wants his room back; he’s losing money while the police are twiddling their thumbs.”

“But why didn’t the sergeant just report it to East Rand?”

The colonel ignored her question. “Sgt. Mfundisi says after he got the forensic results this afternoon, he sat down and gave the matter some thought. He then remembered a case we investigated – he even mentioned the investigating officer by name, WO Ella Neser – of serial killings involving tanned skins. He said he thought he’d share his suspicions with me. So phone him. I have his number – have you got a pen?”

“I’ll get one.”

She wrote it down and ended the call.

Tanned skins. She felt the legs of a millipede on the nape of her neck, peered at the TV screen, saw nothing of interest. Ran her palms across the strings, strumming the first chords of the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun” but giving up, and then sat with the harp between her legs, rubbing the hard callouses on the pads of her string fingers.

“Dammit.”

She sighed, picked up the phone and dialled the number Col. Silas Sauls had given her.

* * *

The hotel owner looked surprised when he opened the door. “You’re early, Detective – it’s not even seven,” said Rabie Saadi. “The cops usually keep me waiting for hours.”

“Sgt. Mfundisi not here yet?” Ella asked, staring at the man’s hairdo: black hair oiled and slicked back, gleaming under the dim lights. The stench of the previous night’s revelry – beer, dust, sweat, sweet perfume and stale food – hovered like thick fog in the deserted bar.

He shook his head. “Coffee? While we’re waiting for His Excellency yet again.”

“Black, no sugar. Your guest, the one suspected of killing a cat in his bath, what’s his name? The sergeant told me, but I didn’t quite get it. Unusual name.”

“Fomalhaut. That’s how he wrote it in the register. Neat handwriting.”

“I want a description for an Identikit.”

“I thought the case was closed? Just a cat, no crime committed?”

“There’s a new development,” she said. “The room remains cordoned off. Did he give a first name?”

Rabie brought out the register, opened it on the bar counter, paged back to six weeks earlier, put his index finger under a name. “This is his initial. Looks like a b, why a lower-case b?”

She looked at the name next to Rabie’s dirty fingernail: Fomalhaut b.

“And why write his initial after his surname?” She thought aloud.

“Why did they send you, a Murder and Robbery detective, to invesitgate the death of a cat?”

“Classified information, Rabie, concerning a current investigation. How about that coffee?”

He motioned her to the nearest chair and ordered two coffees.

“While we’re waiting for Sgt. Mfundisi, tell me everything,” she said. “Start at the beginning. The night your guest, Mr Fomalhaut, arrived. What did he look like? Short, chubby round the hips and thighs, like a pear?”

His eyes jumped to her face. She suspected he’d been assessing her, that he’d concluded there wasn’t much under her T-shirt to get excited about. Rabie’s dancers were much better endowed, swinging from the two shiny poles every night.

“How did you know? I mean, about the chubby hips?” he asked.

“Flat nose, almost no chin?”

“No, sharp nose, crooked. Big chin.”

“Sharp nose? Big chin?”

That wasn’t how she remembered Abel. And she’d taken a good look at him that night in his kitchen when they’d talked and he’d made coffee. Later, after she’d been rescued from his house while he was in the process of removing a piece of skin from her stomach, she had described his face for an Identikit. It was now etched in her memory, and she would never forget it; she dreamt of that face, and of the scalpel in his hand.

Before that near-fatal night, she’d called on him twice at his gallery of African masks and ethnic artefacts. The sparse hair, pale eyes, flat nose; the absent chin, pendulous cheeks.

“Are you sure about the nose and chin?”

“Yes, do you want to take a look?”

“I thought the CCTV lens had been spray-painted?”

“Not the one at reception.”

She took the register into Rabie’s office at the back. He sat down at his computer, fingers wriggling like small eels on the keyboard, and the first black-and-white images appeared on the screen, flickering and grainy. She suspected that Rabie had invested in the cheapest CCTV system on the market.

She could make out the guest’s short posture, but millions of men were built like that. He had his back to the camera and was wearing a hat with a floppy brim that cast a deep shadow over the top half of his face as he bent to pick up two pieces of luggage, his face in profile.

“Stop,” she said. Yes, Rabie was right: sharp nose, the chin so big, almost like a caricature. “Is he wearing dark glasses?”

“Yes, at that time of night,” said Rabie. “Said he’d injured his eye in the collision with the train. I could see the swelling.”

She opened the register again, saw he’d booked in at half past eight, three days after the traumatic events at the funeral parlour of Poppe & Son.

“And these are the only pictures you have?”

“He never came to reception again. Used the fire escape. It was the first and last time I ever spoke to him. I saw him briefly a few times and noticed he was growing a beard. Is he the man you’re looking for?”

She shook her head. “It doesn’t look like him. Where’s Sgt. Mfundisi? It’s after eight. Our appointment was for seven?”

“I told you,” said Rabie. “His Excellency takes his time.”

“Show me the room. I can’t wait any longer.”

“It’s sealed. The sergeant said no one except the cops is allowed inside. Threatened me with prison if anyone breaks the seal.”

“I am the cops, Rabie. He won’t put you in prison. Get the key.”

As she was removing the tape, Rabie said behind her: “Here he is now.”

The sergeant was also chubby of hip, his backside and belly even chubbier, boobs bigger than her own, shoulders like an ox, gait like the waddle of a fat goose. She waited for him to get to her.

“Nothing’s been removed from the room?” she asked.

“Only the bottle with the skin,” said Sgt. Mfundisi.

She thought of the skins and furs found in the tumbledown house in Dorado Park, along with the embalmed body of the old woman, Abel Lotz’s mother, with that weird mask on her face. Tanned skins of cats, moles, hares and dassies, still wet, stretched on drying racks, left behind in his headlong flight ahead of the police.

“Forensics haven’t been here?” Ella asked the sergeant. “You took the bottle with the skin to the lab yourself?”

“Can’t waste Forensics’ time with a dead cat, Warrant. If you don’t think this cat-killer is your man, we can clear the scene, close the file, and Rabie can have his room back. I don’t see anything suspicious. But I thought, just to be on the safe side, I’d tell Col. Sauls about the cat skin, just in case it was connected to your investigation.”

She opened a wardrobe door. “If Forensics examine the room and find something that points to the Nightstalker . . . That’s the only way we’ll know, Sergeant, don’t you think?”

“We went over everything, Const. Xala and I: the entire room and the bathroom, the mini-kitchen with the hotplate and pots and pans and stuff. Over there in the corner is the stuff we found: just a pile of old newspapers. And the skin.”

She looked at the pile behind the door. “He didn’t leave behind any personal belongings? No comb or toothbrush or anything like that?” She crouched at the papers and spread them out. There were also a few magazines: South African Sky Guide, Sky & Telescope Magazine, Deep-Sky Observations. The cold millipede continued its journey down her spine. “Excuse me,” she said and took out her cellphone.

She went into the passage and looked for the number of Dr Verhoef at the Hartebeesthoek Radio Astronomy Observatory. He was the expert who’d looked through Abel’s telescope in his house at Dorado Park and revealed that it had been fixed on the coordinates of the red giant star Betelgeuse.

“Yes?” Dr Verhoef sounded brusque, rushed.

As if the stars could disappear at any moment, Ella thought. As if he didn’t want to miss Betelgeuse’s spectacular implosion.

“Ella Neser here,” she said, tilting her head to look at the black paint on the lens of the CCTV camera.

“Ah, Detective Neser! Still star-struck?”

She was surprised by the change in tone, surprised that he remembered her at all.

“Alas, yes.”

“Still Betelgeuse?”

“You have a good memory, Doc.”

“I don’t often get a visit from the long arm of the law. When a beautiful detective from Murder and Robbery comes to my office, I remember her.”

She let the compliment slide. “This time it’s not Betelgeuse. Or perhaps it is. I don’t know.”

“How can I help?”

“I don’t know how to pronounce it, so I’ll spell it: F-O-M-A-L-H-A-U-T and then a lower case b. Does it ring a bell, Doc, does it have anything to do with the stars, like Betelgeuse?”

“Fomalhaut?” Foam-a-lot, he pronounced it. “You mean the star?”

“A star?” She hesitated, then: “I’d like to come and see you, Doc, if you could spare the time?”

“I always have time for stars.”

“I’m on my way.”

She went back into the hotel room, intending to speak sternly, because she’d learnt that in this man’s world you had to prove you had balls. “Rabie, you may go. I’ll keep you informed.”

“But my room –”

“Thanks, Rabie. I’ll take it from here.” She turned to face him and he scurried out. “Good work, Sergeant,” she said, phoning Col. Sauls and sealing off the room. “The bottle with the skin, was it dusted for prints before you took it to the lab?”

“Er . . . no, but Const. Xala was wearing gloves.”

That was a relief. In the lab they would also have handled the bottle with gloves.

“It could be important, any prints on that bottle. Have Const. Xala take it to Fingerprints. I’ll send for Forensics and Crime Scene Management.”

“What’s going on, Warrant? You’ve found something?”

“Just a suspicion, Sergeant. This room must be processed – every centimetre of it. I want every hair in the bath or in his bed, every fingernail or toenail clipping found. Every fingerprint, every drop of human or animal secretion must be tested, the contents of the shower and bath and basin outlets too. Thanks for your help, Sergeant. We’ll take over the scene now.”

“But what about me? This is my case.”

“Mitzi the cat is your case, not the Nightstalker of Alberts Farm. I’m the investigating officer on this one. But I’d appreciate your help. If you and Const. Xala could start questioning the . . . residents of the Sleep Inn. We’re putting the place under quarantine, Sergeant. No one comes in, no one leaves before we’ve spoken to all the guests. Staff as well, especially the cleaners.”

“What is it you’re looking for?”

“Talk to anyone who had any contact with Mr Fomalhaut, even if they just caught a brief glimpse of him in the passage. If he spoke to someone, I want to know what he said. If someone saw him spit, I want the saliva.” She thought for a moment. “I’m especially interested in whether he asked any of the women about tattoos.”

The sergeant whistled through his teeth. “Rabie won’t like it, his hotel in quarantine.”

“With respect, Sergeant, fuck Rabie. He doesn’t know the man I’m looking for, and neither do you.”

She steered the sergeant from the room by his thick elbow, her fingers already on the keys of her cellphone, calling Lt. Jimmy Julies at Forensics. With the phone against her ear, she reminded the sergeant: “The prints on the jam jar, if you don’t mind?”

* * *

It was Dr Verhoef who had enlightened Ella about the astronomical significance of the skins Abel collected from women. He’d helped her unravel the symbolism of the tattooed peacock cut out of Mia Vermooten’s shoulder, and the hare from Emma Adams’ bosom. Pavo and Lepus, both constellations.

She knew about Abel’s special interest in celestial bodies. It explained her own narrow escape, when he’d begun to cut out the tattoo on her stomach, her shooting star. The tattoo had been for practical and not entirely aesthetic purposes: it had masked an unsightly scar where her appendix had been removed, so that on the beach it was a shooting star that was visible just above her bikini line, not an ugly scar.

But after what Abel had done to her, she no longer wore a bikini. She’d had a close brush with death: first on his butcher’s bench, then as a result of the raging infection caused by his unsterilised instruments.

In his office Dr Verhoef said: “Betelgeuse, as I told you last time, is an old star. Ten billion years old, at the end of its life, a red supergiant in the constellation Orion. And, Detective, don’t believe everything you read on the Internet. Betelgeuse may be at the end of its life, but it could still continue to exist for millions of years. Everything about the stars is relative. Now this one, Fomalhaut, is a youngster. About two hundred million years old, only sixty-four light years from the earth, the brightest star in the constellation Piscis Austrinus.”

“And the b?”

“Fomalhaut b was discovered in 2008 – a candidate planet orbiting its solar star, Fomalhaut, just as our planets orbit our own sun. Is that what you wanted to know, Detective? Have you become an amateur stargazer since our last meeting?”

“Not exactly.” She hesitated: “What does the b stand for?”

“It’s technical. How much time do you have?”

“Never mind, it’s not important. I just had a suspicion . . . Fomalhaut is new to me, but not to someone with knowledge of astronomy. Abel Lotz is an unpredictable, complicated character. If he’d wanted to hide behind a pseudonym, he wouldn’t have just plucked a name from the sky.”

“Well, evidently he plucked one from outer space. But something is still bothering you.”

“A lot of things are bothering me. What does he do with the skins? It’s well known that serial killers often collect mementoes from their victims: jewellery, items of clothing, or something more personal, like locks of hair. Jeffrey Dahmer even kept his victims’ skulls. A piece of skin I can understand, but why specifically tattooed skins with an astronomic significance? And why that size? The forensic pathologist found that the measurements of Mia Vermooten and Emma Adams’s wounds were identical, as if the killer had used a tape measure: 154 by 230 millimetres. Mine was measured too, the area he intended to remove had been marked out with a purple permanent marker: 154 by 230 millimetres. Abel was meticulous and precise in what he did.”

Dr Verhoef’s fingers tapped on his computer keyboard and then peered at the monitor. “Standard paper size for A5 is 148 by 210 millimetres.”

“That’s what we gathered as well: Abel was looking for A5 dimensions, more or less, bearing in mind that there would be shrinkage during the tanning and drying process. Dr Koster says it’s the size of a cheap paperback novel.”

“Paperback novel? In his house, where the telescope was found . . . did you find any documentation, notes about constellations or stars?”

“Nothing.”

“Well, that’s strange. Even amateur astronomers keep notes, write down their observations, usually accompanied by sketches. He’s an amateur, but with advanced knowledge. Perhaps he keeps his notes on a laptop.” Dr Verhoef stared into space. He took off his glasses and pinched the bridge of his nose with his thumb and index finger. “Wait . . .” He turned back to his computer, murmuring, and typed in a search. “Here it is,” he said, reading: “Camille Flammarion. French astronomer, first president of the Société Astronomique de France in 1887. He was also first to suggest the names Triton and Amalthea for the moons of Neptune and Jupiter. A crater on our moon was named after him, as well as a crater on Mars, and the asteroid 1021 Flammario. He also wrote popular books about science, and even more popular science-fiction stories.”

“Oh?” Ella wondered where the conversation was going.

“Flammarion also had a special book in octavo format.”

Not exactly earth-shattering news. “If he was a writer, his books were probably all bound in octavo format at the time,” said Ella.

“Yes, more than fifty titles. But one of his writings interests me, and it’s not his 1907 hypothesis published in the New York Times about intelligent life on Mars. It’s his book Les Terres du Ciel – and it’s the binding, rather than the contents that’s fascinating.”

“The binding?”

“The story goes that a young countess who was in love with him was dying of tuberculosis. She had a piece of skin surgically removed from her shoulder and sent it to Flammarion, asking that he use it as the cover of his next book.”

Ella stared at Dr Verhoef, speechless.

“And if you think that’s fiction,” Dr Verhoef continued, “listen to what Flammarion himself had to say about it, in a letter to an English friend: ‘The binding was successfully executed by Engel, and from then on the skin was inalterable. I remember I had to carry this relic to a tanner in the Rue de la Reine-Blanche, and three months were necessary for the job. Such an idea is assuredly bizarre. However, in point of fact, this fragment of a beautiful body is all that survives of it today, and it can endure for centuries in a perfect state of respectful preservation. The desire of the unknown woman was to have my last book published at the time of her death bound in this skin: the octavo edition of the Terres du Ciel published by Didier enjoys this honor.’ ”

“And it’s a book about astronomy?”

“About the planets in our solar system.”

Ella leant forward. “Is this what’s going on in Abel’s sick mind? Is he collecting covers for astronomical treatises, perhaps for his own observations?”