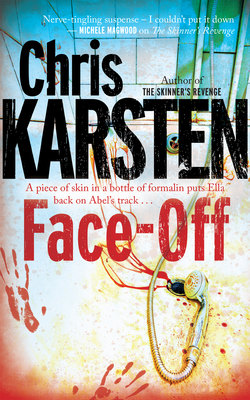

Читать книгу Face-Off - Chris Karsten - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление10.

From behind the lace curtains on the second floor Ignaz gazed at Abel as he walked down Dijver. Quick steps on his short, thick legs, as if resolved on his destination.

Abel was an enigma to Ignaz: he was reserved and inept at conversation, as if ill at ease among people, and yet two donors had given him pieces of their skin. Two women. How had he managed that? What was his secret to convincing a woman to make such an intimate donation, one that unquestionably involved considerable pain?

He couldn’t figure him out, but Ignaz was excited. He planned to cherish and cultivate the friendship, with Sofie’s help. Perhaps Abel could assist him with his own dark obsession. Besides, he was truly sorry for the man – persecuted and hunted in his own country, right across Africa, all the way to Europe. It was unjust and unfair.

And something was wrong with the proportions of Abel’s face, so lacking in harmony and balance. His nose was sharp and asymmetrical, ears like a pixie’s, his chin too large, his skin covered in craters. And all those scars crisscrossing his unattractive face; the legacy of the terrible injuries he’d sustained in his recent accident.

Not the kind of man at whose feet women would fall and offer up their own skin. Ignaz didn’t understand it. He had to admit, though: those last two skins were remarkable. The quality of all seven parchments had surprised him, but especially those last two. In all his decades in book conservation and binding he had never had the privilege of handling anything like them. And he doubted very much whether his father had seen anything like them, or his grandfather or great-grandfather, or any huidenvetter ancestor.

It was clear that Abel had taken particular care with every step of the skinning and tanning process. Ignaz could see, and feel, that Abel had followed his recipes carefully. He could also see that Abel had used the natural tannin of animal brains to oil the collagen tissue and make the proteins in the skins supple.

Later, Ignaz decided, when he and Abel were better acquainted, he would ask him about his donors. Though they had known each other for a long time, their friendship had existed in cyberspace, and now that they’d met face to face it was as if they were strangers. Cyberspace created false friendships, thought Ignaz. Cyberfriendships were without warmth and spontaneity, without human feeling, without the first impression left by someone’s face. Perhaps when he and Abel had shaken off the stiffness of their virtual friendship, trust would develop, and they could begin to share their secrets.

Ignaz would also like to experiment with real virgin parchment, and not just the virgin skins of unborn calves and lambs. Besides, it was becoming more and more difficult to lay your hands on these animal foetuses, and if you could find them, they were very expensive. He would like to hear Abel’s secret. In exchange, he would treat his friend to a meal at Pietje Pek. Their friendship just might lead to a collaboration, resulting in beautiful book bindings textured like velvet and silk.

Down in his storeroom in the basement, where temperature and humidity were regulated, Ignaz kept his stockpile of tanned skins of lambs and sheep, milk goats, calves, pigs and deer, and the smaller vellums made of animal foetuses. He no longer did the tanning himself, but bought his leather and parchments from a tannery in Oudenaarde. Sometimes he imported them from other countries to satisfy the fancies and tastes of his often eccentric clients: leather for the covers of larger books, delicate parchment for copies of rare editions.

But he had to admit, despite his experience and lineage, he had never actually considered using human skin. Though he’d wondered about it.

And now Abel had whet his interest. Seeing that he represented the last generation of bookbinding Boutses, perhaps he also should consider leaving a special legacy. His wife lay in the old cemetery at Ver-Assebroek; his son lived in Brussels and believed the future lay in e-books; his daughter was a sommelier at the five-star Hotel Kempinski, once the Prinsenhof, where Mary of Burgundy had died.

Abel would leave his ten cosmic volumes to an institute in Samarkand, but who would inherit Ignaz Bouts’s legacy? He could still look forward to a number of productive years, and if his partnership with Abel flourished, who knows what might happen.

When Abel vanished from sight at the bottom end of Dijver, Ignaz went upstairs to his living quarters. He opened a door and stepped into his open-plan living room, furnished with a sofa and two big armchairs, the upholstery hollowed out and shiny with use, the patterns rasured like old leather. The room looked as if it were part of a museum, the furniture and décor from a bygone age, and lace everywhere: on the armrests, occasional tables, sideboard, circular dining table and at the windows.

The old wallpaper was scarcely visible behind dozens of framed photographs, all of the same young woman, with little variation in expression and pose – in actual fact, there were only four individual photographs, copied and framed in various sizes. Thirty-six photographs of his Jute, who had died two years after Sofie’s birth, aged twenty-five – the same age as Mary of Burgundy, who died of inflammation after an injury sustained when she fell from her horse. Jute had suffered longer. She’d contracted a virus that had affected the hypothalamus, destroying her brain cells, a rare and incurable metastasis.

Sofie seldom visited him at home. She avoided this memento mori, didn’t understand her father’s undying love for her mother. He didn’t blame her; in fact, he preferred that she didn’t come. This was his private gallery of homage. Under a glass dome on the sideboard was his most cherished relic: a lock of Jute’s hair, which he had cut off on her death. For twenty years he’d preserved it in the vacuum of the domed jar as if it were alive.

The idea wasn’t new: he’d read about it in Bruges-la-Morte, a nineteenth-century book by Rodenbach, though it was just a year ago that he’d come across a rare edition of the book in the Antiquariaat Garemijn in Kemelstraat. He was no book collector, and was often surprised by the personal and sentimental value bibliophiles and bibliomanes attached to certain kinds of books, their willingness to pay fortunes for them. They would then spend another small fortune having them restored, the loose pages rebound in a durable and expensive cover of leather or parchment. Like that old book Il Bestiario Barocco, also known as The Feather Book, in which Dionisio Minaggio, the Chief Gardener of the State of Milan in 1618, had adorned every illustration with authentic birds’ feathers.

It wasn’t so much the contents of books that fascinated Ignaz, but rather the pages themselves, the quality and condition of the paper. Only occasionally did his eye catch something else: a title or sketch, map or illustration, while his sensitive fingers in their cotton gloves unpicked with endless patience the spine of a book to prepare it for a new binding.

One such example was a thin volume of archaeological reports dating from 1848. While he was unpicking the pages, he’d noticed an essay by a man called Albert Way, titled “Some Notes on the Tradition of Flaying Inflicted in Punishment of Sacrilege; the Skin of the Offender Being Affixed to the Church Doors”.

What had really made him think about a special cover for his own old copy of Rodenbach was a client’s request to have a collection of essays from old copies of Notes & Queries rebound. The journals went back to 1865, and in Volume 187, Edition 12, dated 2 December 1944, A.H.W. Fynmore’s essay “Books Bound in Human Skin” had caught his attention.

As he read and reread his Rodenbach book, two ideas had begun to emerge, thanks to the works of first Way, then Fynmore – and now also Abel’s human skin donors. Because Rodenbach’s tale of Hugues Viane was almost identical to Ignaz’s own tale of undying love for his dead wife, he wanted to have his rare edition of the Rodenbach book rebound as yet another tribute to Jute. But for the cover he would need a very special virgin parchment so that he could ultimately store the book, decorated with Jute’s lock of hair, in the sealed bell jar.

He’d searched the shelves in his basement for a soft exotic parchment and had considered several: Russian yuft leather, from the belly skin of a young caribou; morocco leather and even finer saffian; French galuchat, made of sharkskin; shagreen from Turkey, from the skins of skates or rays; chamois from the hide of a young mountain goat in the Tatras mountain range in the Balkans; suede from a gemsbok calf in Namibia.

The question was whether any of those was exotic enough? And of course, after Abel’s almost nonchalant revelation about his two donors, the answer was no.

He would maintain the original cover of the Rodenbach book, as he did with all his clients’ old books. The frontispiece, no matter how damaged and dog-eared, was priceless, and a new leather cover provided protection for the old one against further wear and tear.

The frontispiece of his Rodenbach copy, published in 1892 by Marpon & Flammarion in Paris, was by the Belgian artist Fernand Khnopff, who was also the creator of the thirty-five illustrations inside famous Bruges landmarks, elucidating the story. After all, besides Hugues Viane and Jane Scott, the city of Bruges itself was a leading character in the book.

Ignaz turned away from the lock of hair in the bell jar, and phoned his daughter at the Kempinski, just a few streets from Pietje Pek, where he wanted to treat Abel to Carmelite beer, mussels and eel.

“What’s wrong, Dad?”

“Nothing’s wrong. Can’t a father phone his daughter without anything being wrong?”

“Is it your back again? It’s because you’re bent over old books all day that your back plays up.”

“There’s nothing wrong with my back, Sofie. When are you going to stop working at that hotel? I need you here.”

“I like my work, Dad. I like being surrounded by people.”

“Books are full of people.”

“I like real people, Dad. The ones who talk and laugh.”

He thought of Hugues and said: “People talk in books.”

“Do they talk to you? What do they say?”

“They tell me stories . . .”

“Books are dusty, and dust gives me hayfever.”

Wisely he kept silent about book lice. “Nothing smells as good as the leather and vellum of my books.”

“My nose prefers good wine.”

“A rich guest at the Kempinski is going to take you away from me one day soon. I can see it coming.”

“I’m not looking for a man, rich or poor. Not yet.”

“And if he takes you, I’ll be all on my own. Listen, Sofie, I’ve told you about my friend Abel from South Africa. I want to take him out to dinner. I thought it would be nice if you could join us, meet him, help make him feel at home.”

“Fine, Dad, we can do that. What about your medication? Are you taking it regularly? Should we make another appointment with Dr Smeden?”

“No, no appointment – I’m taking my medication. I’ll phone you about our dinner date.” He put down the receiver feeling guilty about not, in fact, taking his medication. And he could feel it, the anxiety, at night. But he avoided Dr Smeden, who’d been treating him for nerves and depression since Jute’s death. After three stints in the St Raphael insititution in Antwerpen, he had decided: Never again.