Читать книгу A Garden to Dye For - Chris McLaughlin - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

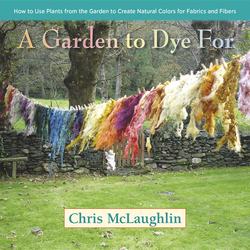

Materials & Textiles for Natural Dyeing

ОглавлениеHere’s where we get into which textiles take color best from plant dyes and how to help them “stick.” We’ll talk about preparing fibers to be dyed and find tips on how to play with modifiers (see below) in order to achieve different colors from the same dyebath.

Plant dyes prefer natural materials, of course! As far as plant dyes are concerned, I tend to stick to natural fibers simply because I can be fairly certain that the colors will take in some way.

While you’re considering what else can be tossed into the dyebath, think about some items that are already in your wardrobe or linen closet that could use a little pick-meup. These items needn’t be white, either. If the fabric will take color, you can dye right over its current shade. Over-dyeing fibers offers endless possibilities.

Generally speaking, plant dyes have a hard time bonding to synthetic (man-made) fibers. But that isn’t to say that all man-made materials will reject all plant dyes. If you want to see what your dyebath will do to a sweater that’s a synthetic blend, by all means, toss it in! The best things happen when you’re willing to experiment.

Protein & Cellulose Fibers

Fabric and fibers that make excellent dyeing materials fall into one of two categories: animal (protein) and plant (cellulose).

Protein fibers are produced by animals. Hand spinners, knitters, and weavers are big fans of these fibers, which include: sheep’s wool, mohair (Angora goat), Angora (rabbit), alpaca, cashmere (goats), silk (worms), and felt (wool). Animal fibers grab natural dye like mad (and quickly), so they’re the perfect choice for someone experimenting with plant dyes for the first time.

Protein fibers (including silk) come from animals. Milk fiber is also treated as a protein . . . yes, you can spin fiber from milk!

Cellulose fibers are produced from plants. Vegetable fibers such as cotton, bamboo, hemp, ramie, wood, basket-making reeds, muslin, and linen are all easy-to-find examples of plant fibers. They’re generally slower to absorb color, so they should remain in the dyebath longer. They can also take longer to prepare if the fabric needs lengthier scouring (see Some Key Words on page xii) and perhaps tannin-mordanted for extra color-fixing (mordant info coming up).

Cellulose fibers come from plants.

It bears repeating that all of these fibers will draw up color differently depending not only on its specific fiber properties, but also how it shows up as a fiber. For example, the wool that you’re dyeing might be raw off the sheep, spun up into a yarn, or woven as a fabric. All three of these will grab color differently because the density is different in all three. Keep in mind that the denser the textile, the deeper the shade of color.