Читать книгу A Garden to Dye For - Chris McLaughlin - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

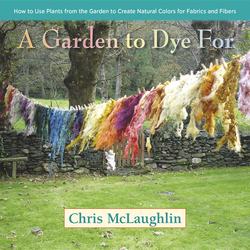

Finding & Collecting Color

ОглавлениеNot all color comes from flowers; even when it does, the flower color doesn’t always dictate the dye color you end up with. Aside from petals, dye can be extracted from leaves, bark (and stems), as well as roots – depending on the plant. Nuts and their hulls are often excellent sources of rich color.

Before we get into some detail on finding color, I want to talk a little bit about collecting the plant materials. As a gardener, I know that I can’t go lopping off branches and foliage as I please or I’ll leave my plant with very little to grow on and may end up sacrificing the entire plant. Unless we’re talking about a noxious weed, this is never part of the gardener’s plan.

The rule of thumb for how much material you can safely remove from a plant is less than ⅓ of any part of that plant. Of course, if you have a bunch of tree trimmings or are cutting a perennial plant or shrub back drastically then your mileage may vary.

As far as ethics and general decency go, you should ask for permission to obtain plant materials from friends and neighbors before you break out the clippers. Here’s a hypothetical example: your parents head to Lake Tahoe for the weekend. You generously offer to “water their plants.” Unbeknownst to them, you casually harvest blossoms here and trimmings there. Don’t do that.

Most of the dyers I know start out by utilizing the plants they have currently growing in their yard or garden. It’s a rather obvious natural progression to one day plant a designated dyer’s garden.

Flowers

Flower heads and petals are usually the fastest dyebaths to make. They’re quick to color up and often produce a lovely scent while they’re on the stove. Generally, flower petal color is at its best when processed in a hot (simmering) dyebath for 30-60 minutes. However, they can sometimes react poorly if they’re processed for too long at high temperatures, so raise the temperature slowly for good control. Another way to extract flower color is to pour boiling water over them and let them soak for a few hours in a non-reactive container.

Leaves

Leaves can often surprise you with some great color, but dye colors from leaves will vary depending on the time of year that you harvested them. So it’s worth it to try vegetation from the same plant in every season. Late spring and early summer are usually the most impressive.

The best way to extract the color is to pour boiling water over the leaves and let them soak for a couple of days. After that, simmer them for about 30 minutes in a dyebath.

Japanese indigo (Persicaria tinctoria) is more widely grown than regular indigo (Indigofera tinctoria).

Berries

Berries can trick you color-wise. Often you’ll find that the color that stained your hands when you gathered the berries changes when it meets simmering water. For others, what you see is what you get.

Crush berries and simmer them for about an hour. Strain the solid berry bits out of the bath before adding your fiber. Or to confine the berry bits, add the crushed berries to a nylon stocking or tightly woven mesh bag and let it soak in the water like a tea bag.

Bark

To get color from bark, it needs to be soaked for at least 4-5 days first (and some people soak it for weeks). After that’s done, put it on the stove and let it simmer for about an hour. Don’t let this bath come to boil, or your colors will be heavily muted by the tannins that’ll be released.

Trees that have fallen or branches that have been pruned are all fair game. I prefer not to harvest the bark from a live tree. If you want to take a little bark off of one spot and then go to another tree and take a bit from there, and so on . . . the tree will probably be able to deal with that. Whatever you do, don’t start peeling the bark off all the way around a tree trunk; the tree may not be able to recover from the damage.

Roots

It has probably dawned on you by now that if you gather roots, this means killing the plant. This is often true, which means that you don’t want to go out and harvest these plants from the wild – unless it’s a noxious weed in your area and you have been given the green light. Many dyers will simple grow them as they would a vegetable; which is long enough to get it to harvestable size.

For example, if you’re growing madder (heralded for the red pigment in its roots), you can plant a madder bed or patch for the express reason of harvesting their roots. In this case, you would wait for the plant to reach its third birthday before harvesting. If you can muster up the patience, a couple more years would be even better. You could use your gardening wiles and plant two or three madder beds, allowing you to harvest one bed each year (after they reached three years old) and replant the bed you harvested.

If you’re interested in trying roots, but don’t want to kill your plant, you can very carefully trim away some of the lesser, side roots (ancillary) and leave the large roots undisturbed. Be aware that the color from the smaller roots won’t be as vivid, however. To prepare them for the dyebath, rinse them until the soil is removed. Then chop up the roots and add them to a pot of water. Lightly simmer for 30 minutes.

I like to soak my walnut husks for weeks to get the deepest browns.

Nuts & Husks

We’ve talked about making a tannin mordant solution from acorns, but they can also be used to obtain mustard-y yellows to gray-browns. Just crush up the whole acorns and soak them in water for 2-3 days. After that, put them in a non-reactive pot on the stove and simmer them for about 2 hours. Strain the acorn bits out of the bath before you add your fiber. Once the fiber is added, however, to keep the colors from becoming dull, heat the bath to just below simmering.

One of my favorite natural dyebaths is with walnuts, or more accurately, walnut husks. While you can certainly use the entire nut while extracting their rich, brown hues, I prefer to save the walnut meat in the middle for fall baking, thank-you-very-much. I remove the green (or brown) husks from the outside of the walnut and pop those into a bucket of water, while placing the remaining nuts in the sun to dry.

Let the husks soak anywhere from two days to several weeks. Simmer for an hour and then strain the husks out of the bath before adding fiber. I should mention that the brown shades will vary depending on when you harvest the walnuts; while the husks are still very green vs. when they begin to turn brown.

In the next chapter, we’ll set up a dyer’s workstation and play with some simple recipes.

Foraging Wild Dye Stuff

If you’re harvesting plant materials from wild and native plants, this becomes a more serious issue. It might be hard to believe, but if people weren’t mindful, it wouldn’t take many foraging dyers to upset the ecosystem for plants and animals alike. So, when you’re foraging wild plants be sure to:

Have permission to be on the land you’re harvesting from.

Know the plant species before you touch it. You want to avoid taking endangered species and you don’t want to mistakenly gather a toxic plant instead of the harmless one. A good example is taking parts of poison hemlock as opposed to the lookalike, Queen Anne’s lace (wild carrot).