Читать книгу A Garden to Dye For - Chris McLaughlin - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Official Endless-Shades-of-Color Disclaimer

ОглавлениеThis may be the oddest disclaimer you’ll ever encounter. Still, it’s important to at least attempt to limit a deluge of emails that could potentially hit my inbox should you not understand this little tidbit about natural dyes. Sometimes even if a recipe is followed to a “T”, you may not get the color you expected. It’s one of the most fun/most frustrating things about working with dyes derived from the natural world.

Half of the truth is that color is nothing if not scientifically explainable. In other words, there’s a logical reason why you got purple instead of true blue from your black bean dye. The other half of this truth is that most of us unscientific types are going to be hard-put to explain exactly why a color went rogue on them. The answer here is “don’t panic,” because usually with a little thought and experimenting the “Aha!” moment does happen and it all becomes crystal clear.

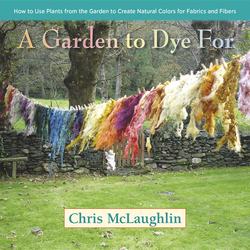

You will be amazed at the color variations that your garden and landscape has in store for you! Before I give you The Great Black Bean Example in Chapter 2, here are some of the most common things that will affect your color results:

The amount of plant material used in the dyebath will help dictate color intensity.

The temperature of the dyebath. Some-times this doesn’t affect a darn thing. And sometimes it affects everything. Example: a black bean dyebath is created by letting the beans soak in cold water overnight. If you heat the bath up, the color just freaks out. No bueno . . . and no blue. (Black beans just happen to be my best example today).

What mordant did you use on your fiber? Or did you skip that part? No worries; you often can. But it will make a difference.

Modify much? You may be thinking that you didn’t use a modifier, so you know that can’t be why you got a color surprise. Are you surrrrre? Could you have made your dyebath in a reactive pot, such as aluminum, iron, or copper – as opposed to stainless steel, ceramic, or glass? Because the sneaky minerals from those first three modified your fiber for sure.

How long you leave the textiles in the dyebath can change things up big time. I’ve used dyes where the final color came immediately and the fiber never needed time to soak in the bath. But I’ve had others that show their true colors only when they’ve been given their due time.

The type of fiber you’re dyeing is a huge factor for both color and colorfastness. I’ve found if something is going to have a difficult time taking color, it’s cotton. So if you’ve already put the effort out to create a dyebath, you may want to have several different types of fibers ready to drop into the pot before you write disparaging notes in your dye journal about a certain plant.

When the plant was harvested often changes the hues. “When” meaning “which part of the season.” Did you gather young leaves and stems in late spring or more mature materials in the middle of the summer? Were those pomegranates young or overripe?

Did you let the plant materials dry before you used them – or did you toss them into the dye pot while they were fresh?

Which part of the plant did you use? Flower petals, leaves, stems, twigs, bark, nuts, and roots will all offer various colors.

Here’s a biggie: your water’s pH. Is it on the alkaline or acidic side? We’ll get deeper into that very soon.

All of that said, there are some recipes in the book that will yield some pretty predicable results, I promise. That’s my disclaimer in a nutshell.