Читать книгу The Shark Curtain - Chris Scofield - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Pablo, When They’re Kissy

Lauren laughs and points at me. “Lily’s got fleas!”

I’m thirteen and I don’t have fleas but I have been scratching and my fingers freeze like dinosaur talons over my arm. When I hold them up and make a face like a hungry T-Rex, my younger sister says I’m “weird,” but she doesn’t know a T-Rex from a T-Bird, or that all birds are dinosaurs, or that Mom’s new car is a 1960 fire engine–red Thunderbird. The Thunderbird is a Mexican bird that went extinct before the dodo did.

“Dodo did.” That’s funny.

“Mom, Lily called me a dodo.”

Our beautiful mother rolls her eyes. She stands at the breadboard making banana-and–peanut butter sandwiches for tonight’s star party. “All right, Lima Bean. Thanks for the APB.” APB stands for All Points Bulletin. Mom smiles at me and asks, “Itchy?”

Yes.

No.

I shake my head and stick my hands in my pockets one, two, three times. I consider the word “itch.” It’s onomatopoeic, which means the word sounds like what it means. I love words: big, small, musical.

Mom says I’m the smartest teenager she’s ever met.

She wraps the last sandwich in wax paper and sticks it in the fridge. Second shelf, left side, piled one on top of the other, folded side down. I open the fridge and double-check that they didn’t shift when she closed the door. I open the fridge and triple-check.

“You find something to wear yet, Lily?” Mom’s distracting me on purpose. “Lauren?”

“Jeez, I can dress myself!” Lauren says as she paws through sweatshirts and cardigans, Gramma Frieda’s ugly crocheted afghans, flashlight batteries, and rolls of star charts on the cluttered kitchen table. “Gross,” she says, pushing aside an ashtray of lipstick-stained cigarette butts.

Mom says artists are messy: “It’s as obvious as that.” Her work shirt hangs on the back of her easel, on the floor a paint-splattered wood drawer holds tubes of paints and dirty rags. She rinses out the big thermos and sets it in the drainer; we’re taking hot chocolate too.

There are three wineglasses in the sink (four yesterday, three the day before), all Mom’s. She cleans them and puts them away. They were a wedding gift from Frieda (Dad’s mom), imported from Portugal, the colors of stained glass. Mom ignores me when I rearrange them so red stands between the green and blue.

We had a late lunch and are saving our appetites until our midnight picnic under the stars. It’s August and meteor season.

Dad walks in with a sack of powdered doughnuts. The “star party” was his idea.

“How much longer?” Lauren whines.

“You tell me.” Dad points at the wall clock, then kisses Mom’s neck, but she swats him away.

No one asks me, though I look at my watch and answer anyway. “Three hours, two minutes, and forty seconds.” I like to be specific. I like the way some numbers are multiples of each other, and others reach into infinity.

The clock over the fireplace chimes. The antique dealer said it was from Eastern Europe, most likely Polish or Czech. Mom’s people are Eastern European. Mom and her sister Jamie were Romanian Jews once, but now they’re nothing. They were sent away, orphaned by the war; they even left their accents behind. The clock makes a deep distant sound like it’s chiming on a mantel far away then bounces off a star in the middle of the ocean before finding our house in Portland, Oregon. The ocean is like the sky, only upside down, and meteors and comets are speedboats flying across it.

It’s time for Sea Hunt! Repeats of course, but who cares? Time will crawl unless we keep busy. I dash to the family room and plop down in front of the TV.

Soon the whole family joins me.

Stupid ads drone on and on. When Edie Adams slinks across the set in a long tight dress, singing about cigars, Dad peeks over his Sports Illustrated and whistles.

“She’s married to Ernie Kovacs,” Mom says, sitting on the arm of his chair. “Bet they’d be fun at a cocktail party, don’t you think, Paul?”

Dad shrugs.

Mom loves cocktail parties. Mom loves cocktails.

Finally the TV screen fills with a watery scene and a voice introduces Sea Hunt’s star Lloyd Bridges as ex–Navy frogman Mike Nelson.

Mom whistles this time.

It’s a stormy day and Mike’s out on his boat with two clients. One, a young guy with Poindexter glasses who doesn’t know how to scuba dive, but his busty girlfriend does. She’s a student of Mike’s and today is graduation, but he suggests she wait a day or two before the final dive. He warns that the water is unusually choppy and muddied, but the girl starts college on Monday. “It’s now or never,” she insists.

Mike frowns. “Stay close,” he says before slipping overboard.

Dad tsks. “Anyone else smell trouble?”

Mom and Lauren raise their hands.

Everything’s fine until they can’t see through the boggy blur of water. Mike spins around cautiously then gestures for her to stay close. A sudden movement behind him catches the girl’s eye . . . and just the smooth gray cheek of a shark is visible before it disappears into the soupy water. Her eyes swell to saucers, and, unable to remember the hand signal for trouble, she points over Mike’s shoulder, then toward the surface. When Mike looks again, he sees nothing. He shakes his head and gives her a thumbs-up.

“That’s right, ignore her. Typical man,” Mom mutters. “Haven’t we seen this one before? Aren’t they all reruns these days?”

“Turn around! Turn around!” I yell.

While the girl finally breaks for the surface, the sleek, gray, pin-eyed animal picks up speed, aiming itself at Mike like a torpedo, its giant jagged mouth ripping a hole through the blurry curtain of water between them.

I throw my hand over my mouth.

On the surface, Poindexter pulls his girlfriend aboard just in time to see the shark’s fin skim by.

Underwater, Mike raises his spear gun and fires into the shark’s mighty mouth. The animal jerks away, and quickly swims off, a trail of blood scenting the water around him.

“Whew,” Mom says in an exaggerated voice, “that was close.”

“It’s all over now,” Dad responds. “He’s history once his friends get a snootful of blood. Right, Lily?”

Mom reaches for the TV Guide. “Another happy ending. What else is on?”

“Lily?” Dad repeats, but I’m still underwater, my air hose torn. Bubbles fill our family room.

Lauren throws a pillow at me and, startled, I yelp. “Dummy,” she says.

“That’s enough,” Dad snaps.

Lauren’s not supposed to make fun of me. It’s a family rule.

* * *

I watch each TV show to the end of the credits, and when Sea Hunt is over, Dad calls us to the kitchen. “Okay, troops,” he says, “meet here at twenty-three hundred, sharp. Take a nap if you need to, but be dressed for the big night.”

Mom pours herself a glass of wine. “That’s eleven p.m., girls. You’ve got . . .”

Lauren tears outside with her jump rope. It’s summer and still light.

“She’s like a grasshopper,” Dad says. “Do you think it’s healthy for her to jump so much?”

“It makes her happy,” Mom says. “That’s good enough for me.”

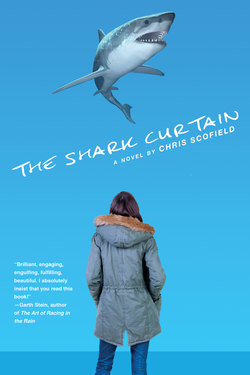

There’s a “shark curtain” in my bedroom closet. Every time I pull the string to the bulb overhead, I see only white and I have to wait for my eyes to refocus to see more. Bad things can happen while you wait. Until Mike Nelson finally saw the shark curtain, he didn’t know he was in trouble.

Each room, as I head down the hall to mine, draws me in. I try not to look. Doors open, lights off, curtains closed to keep out the summer heat, darkness fills each room to brimming. Beyond it are more shark curtains, more blurry darkness.

At the threshold to my room, Mrs. Wiggins, our St. Bernard, lies on her left side snoring. “Sea Hunt,” I explain as I bend down to pet her. Her tumor is hot under my hand and the old dog tenses before she relaxes and wags her tail. Maybe the cancer isn’t as bad as Mom thinks it is.

Maybe Mrs. Wiggins just doesn’t like to be touched sometimes. I don’t.

When I flip on the overhead light, my fingers brush the framed picture of Jesus that Gramma Frieda gave me. His chest is open and His heart is wrapped in roses and thorns, but it doesn’t bleed. He looks down at the art books Mom put on my bed: Leonardo’s Gifts and Pastoral Landscapes of the Romantic Age.

Groovy. Mom never lets me look at her art books.

On the cover of Pastoral Landscapes, a golden sky turns black as it disappears into a blurry stand of trees, a place too thick and dark to make out what’s happening inside it.

In the living room, Mom and Dad laugh and talk. My best friend Judy calls them Romeo and Juliet.

A rock hits my bedroom window screen. “Watch!” Lauren calls from the driveway. “Hot peppers, Lily! Watch!” I count thirty superfast twirls before she makes a mistake.

On the sidewalk behind her, Missy Crenshaw rides her new Schwinn bicycle, smiling and waving like a Rose Festival princess. It’s a warm August night and still light at 9:17 p.m. Across the street, a phone rings and young, blond Mrs. Savage throws down her garden hose and steps inside. Somewhere a baby cries; a dog barks; a golden-oldie radio station plays “Mr. Sandman.” Rusty and Sherman, each in coonskin caps, sit on the curb across the street, quietly loading their cap guns.

I watch Judy the longest. Slouched and sad, she sits in her front yard reading a magazine, but she never turns a page. “If things don’t get better,” she told me once, “I’m running away.” So I watch her intently, looking for anything that would say she’s finally ready to pack her bag and sneak off in the middle of the night. She’s saved her allowance for six months, her babysitting money too.

Where would I go if I was running away?

Mom’s books are big and heavy and full of beautiful glossy pictures.

In Leonardo’s Gifts, I stare at Leonardo da Vinci’s sculptures, focusing on their white empty eyes and marble sex organs; I always thought penises were bigger.

I trace one of Leonardo’s flying machines, paste it into my scrapbook, and glue strips of Mom’s “ratty old mink stole” to its wings. Then I turn to the centerfold of The Last Supper and trace that scene into my scrapbook too. I give the table a long tablecloth painted with stars and planets, and fill the windows behind it with comets. I’ve seen the picture at Gramma Frieda’s church and I know that Jesus’s hand is raised (Dad says He’s asking for the check), but when I look closer this time, I see powdered doughnuts on the table.

And powdered sugar on Jesus’s face.

I slam the book shut and look at my watch.

Mom says I’m good at entertaining myself. She says my imagination is a work of art. The Last Supper is a work of art. Maybe my imagination is on the next page; I saw something like that on The Twilight Zone once.

When I dare to look at Jesus again, He raises an eyebrow and shrugs.

“Stop it!” I yell. Mrs. Wiggins moans and briefly raises her head.

On TV, people who hallucinate famous dead people (like Jesus) are taken to the hospital where they put jumper cables on their heads. They wear diapers and pajamas all day, and cry all night because they want to go home.

* * *

“Crawford Quarry is perfect viewing,” Dad told us earlier. He knows all about the planets and stars, but he still calls Mom his “favorite heavenly body.” He checked out books from the Multnomah County Library and drew star charts that we’ll look at when we get to the pit. He bought us each a flashlight too.

Lauren and I’ve never been to Crawford Quarry, but when our parents told us about the huge pit where people dig rocks out of the ground with big Flintstone-style steam shovels, my little sister giggled. She loves The Flintstones.

At 23:00 (11:00 p.m. exactly), we meet in the kitchen. Lauren’s been sleeping and she’s hard to wake up, but I’ve been watching the clock—listening to the little ticks inside each tock and matching them to my heartbeats; visualizing every step between here and the entrance to Crawford Woods.

“Okay, kidlets,” Dad says, pulling on his windbreaker,“it’s time to go.” Mrs. Wiggins looks up from the floor in the family room and wags her tail. “People are sleeping, but their windows will be open, so no talking. And Lily? Leave your watch at home.”

“Why?”

“Because you look at it all the time, dummy,” Lauren says.

“And none of that, girls, or we’ll turn right around and come home. Got it?”

Lauren and I draw zippers across our mouths.

I grab Mrs. Wiggins’s leash. “Not this time, honey,” Dad says. The star charts crinkle when he pulls a rubber band over them. “Mrs. Wiggins is too sick to go with us. She can watch the house while we’re gone.”

“But what if we need her? Her breed is strong enough to pull people out of snowdrifts. Besides, she’s used to babysitting us. She wants to go.” Mrs. Wiggins wags her tail but doesn’t lift her head.

“You’re being selfish, Lily,” Dad says. His words pierce my heart. “She’s old and sick. You wouldn’t want to be dragged around if you were her.”

“I won’t drag her around.”

The cold water faucet whistles when Mom fills a glass for her evening “happy pill,” and we all turn around to watch. Mom gets unhappy faster than Speedy Gonzales and the pill “gives her balance,” Dad says. “We’re lucky to live in a pharmaceutical age.”

He puts his hands on his hips. “Okay, Asher family. Are we ready to roll?”

Mom smiles; Lauren claps.

“Home no later than three a.m.,” he says. He also says something about the bogeyman and carriages turning into pumpkins too, but Lauren and Mom are already out the door.

I tuck my wristwatch in Mrs. Wiggins’s bed, say a prayer, and draw a pie chart over her, blessing her the way a priest would. “I love you,” I say in Pig Latin.

Dad puts his hand on my shoulder, but I shrug it off.

* * *

It’s a twenty-minute walk from our home on Aiken Street, uphill past the fancy houses in Crawford Heights, to the entrance of Crawford Butte. As we pass the big houses, Mom points out her favorites. Against the dark blue sky, they look like outlines of giant ships. In daytime, they’re all the same: big and white with used brick trim, bay windows, and fake columns, some in the Greek Ionic tradition, some in the Doric. Other columns look like Lincoln Logs or upside-down umbrella stands.

I’d like to build a table-sized Acropolis, paint scenes on the inside, then spin it like a zoetrope. Aunt Jamie said she’d help.

It’s a beautiful night.

My family’s quiet, though inside people’s houses, dogs bark at us anyway. It’s late but televisions light up most living rooms. Jack Paar was Mom’s favorite late-night host but Johnny Carson’s on now. Tonight’s guests are Woody Allen and Ed Ames.

We finally arrive at the dark woodsy path leading to the quarry pit and Dad double-checks our flashlights. He checks that we’re each still carrying a blanket too, and asks after the hot chocolate, tin cups, sandwiches, and powdered doughnuts in Mom’s picnic basket. When he also asks if I zipped my windbreaker, I don’t answer. I’ll be fourteen in two months; I’m not a baby.

Trying to be funny, Dad runs his new binoculars up and down Mom’s legs. “Ooga, ooga,” he jokes. Judy says he bought them with money he won at the horse track, but how does she know?

Dad walks ahead of us, kicking an empty can out of his way. It’s motor oil, probably for the motorcycles that tear through Crawford Woods all hours of the day and night. There’s an empty wine bottle in the bushes too, old yellowed newspaper, and dirty Dixie Cups.

“Litterbugs,” Lauren says, leaning into me. Messes make her nervous.

Mom and Dad stop where the trees begin to darken and blur and I stop too. “Wait a minute,” Dad says, turning around. He sniffs. “What’s that?” It’s his teasing voice. “Does anyone else smell it?”

Mom turns her flashlight beam on him. “Paul,” she warns.

He sniffs again. “Is that . . . carrion?”

“What’s carrion?” Laura asks.

“Come on, Paul. No ghost stories. You promised.”

“All right, all right.” He smiles, and taking Mom’s hand finally leads the way into Crawford Woods. When they slip out of view, my sister and I hurry up behind them. Every five steps, I stop and listen.

“Mom?” Lauren calls out. “Lily’s—”

“Use your flashlights if you need them,” she interrupts.

The dirt trail is soft and dusty, and except for the picnic basket bumping against Mom’s leg, Dad’s crinkly star charts, and Lauren’s heavy breathing (Mom says she needs her adenoids out), it’s a quiet walk through Crawford Woods.

Up ahead is the basalt quarry, the bombed-out crater, the hole all the way to China. Up ahead is the giant mouth of the pit and the meteor-filled sky.

The path narrows and widens, narrows and widens, like the giant walk-through lung at the science museum. Where the trees disappear, the woods become a wall of black. I want to be brave like the Indians on TV, to ride into battle screaming my head off and eat the hearts of my enemies. I want to stop walking and look into the shadows where the shark curtain lives but I’m afraid. I’m afraid of places like the blurry landscapes in Mom’s art book, where angry elves keep escaped circus bears as slaves, or gargoyles sit in the bushes watching me stumble by.

My fingers twitch as I “pretend type” a prayer on Frieda’s typewriter. God bless Aunt Jamie and Mrs. Wiggins and . . .

The trail gets narrower, pressing against us. “How much longer?” I ask.

“Not long,” Dad answers. He directs us to turn off our flashlights and “trust the stars, your eyes will adjust.” For three or four minutes (it could be longer; I don’t have my watch) Dad whistles the theme song to The Andy Griffith Show.

The woods smell like the sweet-and-sour soup they give you before the good stuff at Ming’s Chinese Garden. “Smell the musk?” Mom asks. “It’s nettles. Be careful, they’ll sting.”

I stop and sniff. The smell is strong and getting closer.

Nettles and soup, but more than that too. Something familiar that isn’t the raccoon poop in Mom’s flower bed; isn’t Dad’s wool army coat, dog chow, or the cold cement floor in the garage. Something else is in the air. A whole lot of something elses. I hurry a little and accidentally step on the heel of Lauren’s shoes.

“Dummy,” she mumbles.

Suddenly, a huge bird darts over our heads and Lauren gasps. “An owl!” Mom shouts and, pretending to be scared, hurries to Dad’s side. I read that owls are warnings, sometimes of death, sometimes of danger.

The others walk on, but I stop, then take three short breaths and inhale deeply. Exhale. Repeat. Three short breaths (for the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost; for Mom, Dad, and Lauren) and inhale deeply. Exhale. Repeat.

The scent is some combination of familiar and unfamiliar, but sticky sweet and wet too. I open my arms like crucified Jesus, stretching my fingers and bugging my eyes, and make myself into a smell antenna.

The scent is coming toward us: the closer it gets, the more it fills my lungs . . . The more it fills my lungs, the more the ground vibrates under my feet . . . The more the ground vibrates under my feet the more the smell vines up my legs like a pea plant until the stink and sound and vibration slip through my ears and nostrils, filling me up, inflating me like a rubber balloon, or Jiffy Pop. Will I explode before it gets here?

“Mommmm!” Lauren flips on her flashlight and walks back to me. “Lily’s being weird again.”

Listen, can’t you hear them . . . ? Dozens of snapping sounds and growls, panting breaths, high-pitched barks, and finally the smell—I recognize it—the warm dusty smell of dry soft dirt, a cloud of it pushed ahead of their thrumming, drumming feet.

How close? I fall to my knees and press my ear to the ground.

“Lily! For God’s sake, stand up.” It’s Mom. I see the toes of her dusty white deck shoes. They’ll be washed and sitting in the morning sun by the time I get up tomorrow. “Lily!” I feel her warm worried hands on my shoulders. “Paul!” she calls.

“I’m okay,” I say, or try to say. But dogs don’t talk.

I smell their hot sour breath and wet fur as we race through Crawford Woods together, their thick muscular bodies brushing mine as we run side by side, feeling the tendons in my legs stretch and contract as I run—only I’m big and slow and sick and I fall behind the pack . . . behind . . . slowing . . . slowing . . .

Then find a burst of energy and rejoin them. My face is wet with the saliva that flies off the tips of their long speckled tongues. Their fur brushes my face, their musk fills my nose. When the hair on my arms stands up, they recognize me. I’m one of them. In a blur of dust and dirt, claws and fur, we nip at each other, yip, and bark.

“Lily!” It’s Dad. “Can’t we do one simple family thing together without you . . .”

On my knees in the starlit woods I see what Mrs. Wiggins sees with her tired milky eyes; flying over stones and potholes, struggling to focus through the cloud of soft thundering dirt while dry prickly brush whips her face, she keeps going, putting on even more speed when she sees her family, us, up ahead on the trail.

The others will fly past us before she does, but somewhere up the trail the dogs will slow down. Then. Finally. Stop. They’re only pets, after all, out-of-shape purebreds and mutts, not feral dogs, wolves, coyotes, or (their distant cousins) bears; no T-Rexes or Thunderbirds. Finally, they’ll wander home (Mrs. Nelson is calling Offie right now), exhausted.

But proud they didn’t forget: they were wild once.

They’re nearing us! The heat of the pack, the yelping, the dust—

Suddenly Dad cries, “Off the path! Now!” And my family jumps, making startled complaining sounds when we land in the brush, seconds before the dusty snarling dogs race by.

I raise my head and watch Mrs. Wiggins lift off the ground. Floating above the others, she looks back at me with her milky eyes, and her warm cancerous breath heats my face.

“Thanks,” she says in Pig Latin.

* * *

“Everybody okay?” Dad calls. His flashlight bleaches the trail. It finds Lauren. “Lima Bean?”

Lauren nods. She looks scared and confused. Her freckles spring on and off her face like Mexican jumping beans.

“Lily?”

The muscles in my legs relax as I pull sticks and vines out of my hair. The thick callous pads on my feet dissolve. I’m still panting from the run, and chilled by sweat I stand up in the bushes and press my hand to my burning chest.

“Okay?” he repeats.

Yes. No. “Okay,” I say, clearing my throat.

“Kit?” Dad shines the light on Mom, curled around him. “There you are,” he jokes, kissing the top of her curly auburn head. They found each other first; they always do.

Mom laughs too, then reaches for the picnic basket and says, “Whew! That was wild! Where’d they come from?”

I know. My eyes are good at night. I recognized some of them, dogs from the neighborhood: the German shepherd from Sherwood Court, two yellow labs, the old boxer, the chubby beagle, the short-legged Lassie.

At the entrance to the quarry, Dad unhooks the chain gate with the No Trespassing sign and gestures us through. “Bet the dogs passed here hours ago,” he laughs.

Mom smiles, but Lauren and I don’t. We glance at each other. The dogs were cool but it’s wrong to break the law like Dad is.

We follow our parents into the starlit open sky. The trees stand back from the big hole, silhouetted against the clear night sky like rows of spears. The heat of the day still clings to the barren ground. It’s a weird place, like the surface of the moon in comic books. Lauren slips her hand in mine. She looks around for the Flintstones’ steam shovels, but they’re nowhere to be seen.

“Don’t forget what I told you about . . .” Mom peers at the sky. “Look! There’s one!” She points at the twinkling star mass. “How beautiful! There, did you see it? Stars, meteors, everywhere!”

Meteors fall around us without touching the ground; they hang in the trees and shine in Lauren’s red hair.

When Mom calls the stars “kisses from angels,” Dad grabs her and kisses her on the lips.

“Girls?” Mom starts again. “You remember what we discussed about the pit, right?”

Lauren puts her flashlight beam under her chin. “Do I look like a jack o’ lantern, Mom?”

“I take that as a yes then?”

“Stay away from the pit,” I answer for us both.

“Is that your jump rope?”

“It’s my lucky charm,” Lauren explains as we lay out our blankets. My sister doesn’t go anywhere without her jump rope. Sometimes she loops it over her bicycle handles or wears it as a belt; tonight she carries it in her afghan.

Lauren jumps rope, chews gum, sucks her thumb, and throws up because of anxiety, bad ears, and motion sickness. When Mom told Dr. Goodnight that Lauren was a “nervous child, a perfect candidate for ulcers,” he smiled and wrote Mom a prescription for more happy pills.

“A rabbit’s foot would be smaller,” Mom said to her.

I got in trouble for burning my rabbit’s foot, even when I explained that it was the only way the foot and rabbit could be reunited. I read about it in Aboriginal Tales.

“Ladies!” Dad barks. “Can we please be quiet and watch the stars? Isn’t that what we came for?”

That’s not a real question; neither one of them are.

Lauren and I don’t get close to the pit. Okay, maybe just a little. On top of Gramma Frieda’s afghans we pretend to be astronauts; the starlit white rim of the pit is the outline of the moon. My blanket is a flying carpet, a floating island where I sit and walk my fingers across the sky, leaping over meteors.

Mrs. Wiggins loves the sky. When it’s a full moon, I don’t have to look outside, check the tide chart, or The Old Farmer’s Almanac, because Mrs. Wiggins jumps on my bed and stares out the window, so I know it’s full. Now that she’s sick and old, she pees a little when she jumps, so Mom covers my bed with old towels.

I wish I could read Mrs. Wiggins’s mind. I tried her on a Ouija board once—shoved it under her nose and waited for her to nudge a series of letters that would spell out something—but she didn’t like it. She’s private, like me. After school one day, I found its chewed-up pieces in her dog bed.

When we finish our picnic, Lauren and I lay back, counting meteors out loud and laughing. After a while, we hear our parents whisper and Lauren shines her flashlight on them.

“I knew four flashlights were too many,” Dad says, turning his back to the beam. Mom lies beside him. He gives her a noisy kiss.

“Oh, Pablo,” Mom giggles. She calls him Pablo when they’re kissy.

“Oh, Pablo,” Lauren mimics, making loud smoochie sounds on her arm.

“Girls!” Dad snaps.

With my index finger I connect a series of stationary stars, and draw Mrs. Wiggins’s outline in the twinkling sky. A new constellation: Canis Wiggins.

“Lily, do the dogs run through the woods every night?”

I shrug but Lauren isn’t looking. I guess she asks me questions I can’t answer because I’m older than she is. Plus, our parents are making out, so she can’t ask them either.

“Mommy and Dad-dy, sitting in a tree,” she sings as she jumps rope. I smell the dust kicked up with every twirl. The ground thumps when her feet land together. “K-I-S-S . . .”

In the dark, on another flying blanket far away, Mom giggles.

“First comes love, then comes marriage,” Lauren continues.

Mrs. Wiggins’s water dish is in the stars too. And a cartoon bubble over her big square head that reads, STAY AWAY FROM THE—

Suddenly there’s a skid, and the rope stops turning. A thump. A moan.

Lauren! I jump to my feet.

“Lily?” she whispers.

“Lauren?” I whisper back.

“Girls?”

“Mrs. Asher, please!” Dad is being silly. “Your lips, the stars. Your lips, the stars.”

“For God’s sake, Paul, let go!” Mom flips on the flashlight and hurries toward us. I’m blinded by the glare. She quickly puts it down, and turning the beam away illuminates the gray scraped wall on the opposite side of the quarry.

“What’s going . . . Where’s . . . Lily, what are you doing?”

On my stomach.

Hanging my head and arms over the lip of the big black hole.

Reaching for my little sister.

My body flexes and stretches, the muscles lengthen, tighten, and grow strong; I smell the dogs’ musk, and feel their deep excited growls in my throat. Somehow I have one end of her jump rope. When I tug at it, Lauren looks up. She’s easy to see under a sky of bright stars that light her pink barrettes and the shiny tip of her sun-blistered nose. She stands on a tiny shelf, just out of arm’s reach, and clutching her end of the jump rope leans against the quarry wall, breathing heavily.

“Lauren!” Mom gasps as she kneels beside me. “Oh, Jesus!”

Dad turns his flashlight beam on Lauren, who blinks and closes her eyes. “It’s okay, Kit, we’ll get her out. She’s right here on a ledge, only a couple of feet away. She’s fine.” He clicks off the flashlight and hands it to Mom. “Daddy’s here, Lima Bean. I gotcha.”

He straddles me and wraps his hands around mine.

Doesn’t he see me? I’m not invisible.

“Lily, let me do it. I’ll pull her up.”

Lauren’s eyes shine with tears. “I’m scared,” she says quietly.

“I know,” I tell her. “When you feel me pull the rope, hold on real tight, okay?” Lauren doesn’t answer. “Lean against the rock and I’ll pull you up. If you feel another ledge, step up on it.”

I can do this. We can do this. I feel Mrs. Wiggins crouch beside me; I smell her hot rank breath.

“Lily,” Dad says sternly, “give me the rope. Let it go slowly.”

I ignore him. “Lean against the rocky wall, Lauren,” I say. “I’ll pull you up.”

“But it’s dirty.” Lauren hates being dirty.

“I know, but you can take a bath when we get home.” Mrs. Wiggins’s wet nose smudges my leg. Her toenails scratch the dirt. Somehow she’s behind me, ready to pull with me. “Just hold on really, really tight.”

“Lily,” Mom says, “let Daddy do it. He’s stronger than you.”

“No.”

“This is no time to be stubborn!”

“NO!”

“Please, Lily! Lauren’s in danger!”

“I am?”

“Lily!” Dad barks.

“NO!” I yell at them both. “Go back to your stupid kissing!” I don’t take my eyes off Lauren. “I won’t let you fall,” I tell her quietly. “Promise.”

I scoot backward and pull on the jump rope. The dirt and gravel scratch my stomach and then I do it, we do it, somehow we pull her up—Mrs. Wiggins, and maybe Dad and Mom, but mostly me—and Lauren slides up over the edge, out of the pit, flat on her belly, dirty and scared and whimpering.

Mom hugs Lauren to her big soft boobs. “Are you all right?” she asks while looking her over with the flashlight. Finally she looks at me. “Why must you always challenge us, Lily? Why can’t you do what we ask? The rope could have slipped from your hands, and then what? If your father hadn’t been there to pull her up . . .” Mom starts crying all over again. When Dad pats her shoulder, she lets go of Lauren and grabs his hand. “Oh God, Paul.”

Shouldn’t my sister be more scared than Mom?

Lauren climbs out of her lap.

“If you won’t listen to your father, Lily, then listen to me. We can’t protect you if you don’t do as we ask.”

“But you were kissing,” Lauren says. She twirls the jump rope, walking instead of jumping, stepping over it when it stops at her feet.

“Lauren! Put that damn thing down!” Mom says. “You’re the older sister, Lily. How many times have I told you—”

“Yeah.” When Mom yells at me, my voice gets small.

“Yeah? What the hell kind of answer is that?” Mom sniffs. “We’re your parents. If you don’t listen to us here, how can I trust you at Peace Lake?”

Peace Lake is our favorite family vacation spot. It’s also where Aunt Jamie swims. And me. And sometimes the whole swim club, the one thing I do with kids my age besides go to school. I’m a good swimmer, one of the best on our team; there’s a competition next month, but even if I win no one will care. No one talks to me at school or on the swim bus. Lauren says it’s because I’m a “weirdo.”

“Lily!”

“Okay.”

* * *

Dad carries Lauren on his shoulders as we walk out of Crawford Woods. She’s ten years old and “too big,” but he does it anyway. She carries the unopened star charts and every once in a while looks back at me. The jump rope is draped over her shoulders. “Dummy,” she says with a smile.

“Dummy,” I smile back.

The night air is thick and stuffy. Humid, Mom calls it.

The woods are throwing us out. They’ve had enough, they want us to go. We embarrass them with our clumsy, weirdo, pill-popping, gambling stuff. When Dad says, “I’ll bet each one of you a Hostess Cupcake it’s after two a.m.,” Mom throws a dirt clod at him. He pushes a button on his wristwatch and announces, “It’s two thirty.”

That’s one hundred and fifty minutes past midnight.

Back home, drawers stick out and closet doors stand open.

We should hurry. Things get out if you’re not careful, things get in.

* * *

What I wish had happened next:

“Let’s all sleep in,” Mom suggests. Then, “Waffles with whipped cream and strawberries at ten!”

Mom talks a lot when she’s tired. Or scared. Or excited. She talks a lot on our way out of Crawford Woods that night. Mom talks about being nearly trampled by a pack of dogs. She calls me her “hero” for rescuing Lauren, and sings, “Hi-Lili, Hi-Lo . . .” I blush, but I like her singing. She talks about school starting in three weeks, and how Lauren and I need new coats.

“Let’s go shopping tomorrow,” she says.

“Yippee!” Lauren yells. She loves to shop.

I hate shopping, but maybe I’ll go this time.

Minutes later, with Mom in the lead, we sing “Kumbaya” as loudly as we can. She balances the picnic basket on her head, like one of the African women in her paintings, while comets fly through the trees.

We talk about Maxwell Smart’s old phone-in-the-shoe trick, and The Man from U.N.C.L.E, and Mom asks Dad to say something with a Russian gangster accent. “Oh, Pablo,” she swoons, and everyone laughs.

* * *

What really happened:

After a while, Lauren yawns and leans against Dad, half asleep.

“The Perseids are beautiful,” I say to no one in particular.

Mom’s still mad. Dad whistles the first few bars of The Andy Griffith Show song, then stops.

I see something in the bushes and fall behind.

“Lily?” Mom calls over her shoulder.

“Got to pee. Just a minute.”

“Good job, kiddo,” says the voice in the dark. I can’t see His face but I know it’s Jesus; His voice is quiet and deep like in Bible movies, and stars light the shoulders of His robe.

I don’t answer. Maybe if I ignore Him, He’ll go away.

“Saving Lauren,” Jesus repeats. “Good job.”

If I talk to Him they’ll put jumper cables on my head, stick me in pajamas and diapers, and I’ll never go home. Never eat waffles again or get a new school coat.

“Lily?” Mom calls again.

“Coming!”

If Jesus were really here right now, I’d ask Him why He didn’t help me save Lauren; the Bible is full of bigger miracles than that. I’d ask Him what’s wrong with me; why even my skin feels weird these days. If Jesus were standing in front of me in the woods at three o’clock in the morning, congratulating me on saving my little sister, like He is, I’d ask Him why He’s bugging me.

Does He want me to wear jumper cables?

Doesn’t He love me like the Bible says?

“Now, young lady,” Mom calls.

I turn and start up the path.

“Sure, go ahead,” Jesus says behind me. “I’ll catch up with you later. Say hello to Mrs. Wiggins for me.” I hear a twig snap as He heads off into the brush. Why doesn’t He fly? He walks on water, doesn’t He?

I rush to Mom and fall in step behind her.