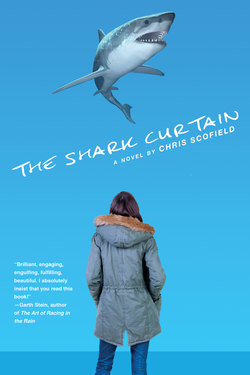

Читать книгу The Shark Curtain - Chris Scofield - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

The Swimming Ribbon

Three things have happened since Jamie last came to Sunday dinner:

1. The pit.

2. I saw Jesus riding on the back of the garbage truck.

3. I lied about the swim contest at Peace Lake. No one knows I lied, and my lie didn’t hurt anyone, but it still bugs me. I want to be a good person, and Aunt Jamie says, “Lies make your guts hurt.”

My guts have been hurting for days.

“It’s lush and lanky Lily Lou!” Jamie cries as I open the door. She likes words too. When she sees our old dog standing beside me, she kneels down to face her. “And the wonderful Wanda Wiggins,” she says quietly. “Can’t leave you out, can we, girl?” When Mrs. Wiggins whines and wags her tail, her hips tip to one side and she stumbles a little. “Poor thing.”

“How do you know what her first name is?” Lauren asks.

“She told me.” Jamie winks. “Nice pink umbrella. New?”

The umbrella over her head, Lauren twirls in place on her tiptoes, humming “Waltz of the Flowers.” She wants to be a dancer. Or a dentist. Or a Southern belle; she’s just seen Gone with the Wind.

“Why, yes it is,” she says in her best Scarlett O’Hara. “Mother took me to the 99-cent store and said I could have anything I want. I just love the 99-cent store.”

“Me too. Especially the bins of cheap imported toys.”

When something bad happens, Mom goes shopping. She took Lauren the day after the pit.

“I heard about what happened at the quarry,” Jamie says. “Everybody cool?”

In the kitchen Mom winds the oven clock, then takes down the Sunday china and stacks it on the counter.

“We’re cool,” Lauren smiles. “Hey, are you a beatnik, Aunt Jamie?”

“A beatnik?” Dad calls out. “Not our Jamie! Maybe a hippie—”

“More like a bohemian, I guess. A nonconformist.” Jamie smiles at me. “How’s my favorite mermaid?”

“Fine,” I lie. My stomach is wringing out towels.

“The big family day at Peace Lake is tomorrow, right? It’s smart of your family to go on a Monday; you’ll probably have it all to yourselves. You can bring your pink umbrella, it’ll keep you from burning,” she says to my fair-skinned redheaded sister, “and you,” she beams at me again, “can swim out as far as you want. Excited?”

“Yep,” Lauren says. “Want to see me jump rope? I did thirty-six hot peppers without messing up.”

“Thirty-seven,” I correct her.

“Later, maybe,” Jamie says to both of us. “Excited about school?”

“Yep.”

Jamie sniffs the air. “Chicken and dumplings?”

“Yep.”

“Yep is not a word, Lauren,” Mom lectures from the kitchen. “Do I hear the voice of higher learning? Has my sister finally arrived?”

“Come in! Close the door.” Dad’s at the dining room table reading Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People. It’s a loan from our neighbor Mr. Marks, Judy’s stepdad.

“For God’s sake, Paul,” Jamie giggles, “ever heard of fresh air? It’s seventy-three degrees out.”

“Better be warmer tomorrow, if anyone’s going swimming.”

Lauren, Jamie, and I take our positions at the dining room table. My sister looks at the salad bowl and crinkles her nose.

“Come on, Kit, let’s eat!” Dad bellows. “It’s dangerous to keep a hungry man waiting.”

Jamie shakes her head. “I thought my sister had you better trained. I swear, I’m never getting married.”

“Unless, God forbid, you fall in love,” Mom says, appearing in the doorway with a tureen of chicken and dumplings. Everyone applauds. It’s my favorite giant soup bowl—its two long-eared white rabbits serve as the handles.

“Wait, wait, I almost forgot,” Jamie says with excitement. Mrs. Wiggins slips under the table as Jamie dashes to the family room to dig through her satchel.

Mom sighs. “Can’t it wait until—”

“Absolutely not! I thought it would be fun to talk about something different over dinner. Find out what the girls’ opinions are for a change.” Jamie is the grooviest aunt ever. When she sits down again, placing a thin black book next to Mom’s fancy salad bowl, a curtain of long red hair falls forward, brushing her arm. Jamie is beautiful. Even Mom says so.

“A book?” Dad lifts an eyebrow. “Okay, James, talk. But if my dinner gets cold, we’re eating at your house next time.”

“Before we dig into another one of Kit’s beautiful meals, I want to present Lily with this gorgeous homemade ribbon for taking first place in last week’s Race to the Pilings!” Pressed in the book is a purple ribbon with my name in silver glitter. “Ta-da!”

My stomach does a backflip, nearly knocking me out of the chair.

Lauren reaches for the ribbon. “Can I have one too?”

“Only when you become a master swimmer like your sister, Lima Bean. Only when you brave the dark, cold, treacherous waters of Peace Lake,” Jamie says dramatically, “to reach the half-submerged pilings of the ancient Floating Doughnut Shack.”

“Ancient?” Dad says, pouring wine. “It only burned down ten years ago.”

“We’re talking halfway across the lake, Paul,” Jamie says. “That’s impressive at any age.”

Mom’s suspicious. “What have you two been up to?”

Jamie looks at me. “You didn’t tell them?”

Mom doesn’t like it when Coach Betty moves swim practice away from the YWCA. “The team went to Peace Lake,” I say.

“Again? I don’t remember being notified. What if—”

“No what-ifs. No big deal,” Jamie says, helping herself to the Waldorf salad. “Other moms came along; there was plenty of supervision. I was up there already. It was a beautiful day—just a hint of fall in the air.”

Mom looks confused. “Did you bring a slip home, Lily? Did I see it?”

I nod.

“Did I sign it?”

I nod again. It’s true but my stomach hurts times pi. The only thing worse than lying is making Mom feel bad.

We take turns passing her our plates and watch quietly as she serves each one of us a dumpling that she smothers with chicken and gravy. She finally slips into her chair. “Huh,” she says, surprised at herself.

Mom forgot to buy gas last week too, and a tow truck brought her home. Her car was full of groceries and when the truck guy helped bring them inside, Mom said he “made some crack about all the wine I bought. He thought we were having a party. It’s none of his damn business what I buy.”

Everyone eats until Jamie pats Mom’s arm. “I forget things all the time,” she says, finishing her second glass of wine. “It doesn’t matter. The lake was great, Kit. The water was delicious and the girls are such strong swimmers. Of course, Lily took the cake.”

Lauren perks up. “We’re having cake?”

“You’d have been proud of her, Kit!”

Don’t be proud of me. I didn’t get to the pilings; I had to stop. My body weighed a ton, and I was out of breath. I dog-paddled in place until Theresa and Carol swam by, then joined them swimming back to shore. They reached the pilings but I didn’t. On the beach, Jamie stood next to Coach, clapping her hands and whistling. Mom and Dad like it when I do something with “kids my age,” but it only mattered that Jamie applauded. When she did, I forgot all about the pilings.

Kind of. If I had a time machine, I’d take back everything that happened that day.

“But Peace Lake is hell and gone,” Mom says. “I should have remembered.”

“It all worked out,” Dad says. “No harm done. Lily’s an ace swimmer, remember?”

“Don’t patronize me, Paul. It’s important that I remember.”

“Ta-da!” I hold up the ribbon. This time it says, Liar.

Lauren loves round things. Eggs, baked onions, pancakes, Cheerios. She wolfed down her dumpling, made circles in her gravy, and pointed at Aunt Jamie’s book. “Are we going to talk about your book?”

“Yes,” Dad says. “What is it?”

“Only the most amazing thing with the most amazing pictures you’ll ever see,” Aunt Jamie announces. Her eyes twinkle.

“Have you considered a career on stage?” Dad asks.

Jamie pats the book like Reverend Mike does after he reads a Bible passage to the congregation. “It’s called A Child Is Born.”

My parents exchange looks. “That’s really not appropriate for the dinner table,” Mom says. She picks it up and puts it down again. “Were you actually going to explain all this to the girls? These are things we talk about as a family. You should have asked us first.”

“It’s about the miracle of life, not the act of procreation.” Jamie takes a big gulp of wine.

“I know what it’s about,” Mom says.

Ever the copycat, Lauren says, “I don’t want to look at the book.”

“See?” Aunt Jamie shakes her head. “Ignorance is contagious.”

Mom sighs. “More salad, girls?” Lauren and I both stare at her. We’re kids; we don’t eat rabbit food. “Garlic bread?” Mom unwraps the foil log. “Still plenty left.”

We all reach for it.

“Do you know,” Jamie says, tearing off tiny pieces she quickly stuffs in her mouth, “that we’re all one sex until Mother Nature decides what she needs us for?”

When Jamie says sex, Lauren covers her ears.

“Chromosomes determine our gender, but before XY and XX play out, the fetus has everything it needs to be both sexes. The embryo is male and female. We even have tails like tadpoles do, for a while anyway. Far out, huh?”

Maybe I’m a boy and a girl. Maybe my tail is stuffed up inside me. “Yeah,” I say. “Far out.” I lean forward with excitement, resting my elbows on the table.

Mom points at my plate. She wants me to eat up but it feels wrong to eat chicken right now. We studied chicken embryos in class, even though the incubator was accidentally turned off one weekend and all the eggs died. Frieda said something was wrong with the baby chicks and God didn’t want them to live. Mom said the custodian probably tripped over the plug.

“It’s called . . .” Jamie looks at the ceiling. “Um . . .”

“I’ll look it up,” I offer. “Is it in the book?”

Mom holds her index finger to her lips to shush me. She’s worried I might get “too excited.” Maybe it’s the boy chromosome in me that makes me do stupid stuff. Sherman and Rusty do stupid stuff all the time. “Have another glass of wine, sis. It’ll come back to you.”

“Go ahead, James,” Daddy laughs, “enlighten our impatient little naturalist-in-training. Explain how the same sex glands and genitals develop in both sexes.”

“Dad-eee,” Lauren whines.

Two embryo-shaped dumplings do the backstroke in the cooling soup tureen.

Jamie slaps his arm. “It doesn’t matter what it’s called, Paul. It’s just a word, but the idea, the scientific fact, is deep. That we create each other is amazing! Isn’t it, girls?” She takes turns smiling at all of us.

“It’s a miracle!” I cry, and accidentally kick poor Mrs. Wiggins under the dinner table. She moans; I must have hit her tumor.

Mom drops her fork. “Is the dog under the table, Lily? I said no, didn’t I? Mrs. Wiggins is sick. She smells bad. You know better.”

“That’s a perfect example,” Jamie says. “Science is bursting at the seams. In the future, Mrs. Wiggins could be cloned. We have the capacity to do so many incredible things! What if people had the option of being both sexes? Or neither sex? What would being human mean if we could reshuffle the chromosomes and be something completely different?”

Dad laughs. “You mean like a hermaphrodite?”

Mom throws her napkin at him.

This is the best, most grown-up conversation of my whole life.

“We could reinvent the world, create new foods that could save mankind! What if,” Jamie says, turning to Lauren and me, “there were real mermaids and giants and DayGlo jungles? And lichen tasted like coconut, and we could take elephant rides on the moon?”

“Wow!” Lauren says.

Mom smiles. “Wow is the word, all right. You’ve been reading way too much science fiction, sis.”

Jamie takes a big gulp of wine. “Okay, maybe I’m exaggerating a little, but if we have the science for it, why not the imagination? What are we afraid of? What’s so special about all these overpriced toys, anyway?” She glances around the room, holding out her arms like the TV game-show model Carol Merrill. “When we could have a more meaningful and . . . interesting life. You’re an artist, Kit. Don’t you want that?”

Mom scowls at her. “They’re not toys, Jamie. We work hard to have nice things. There’s nothing wrong with nice things.”

“I know, I know, it’s just that . . . we have to change, Kit. It’s almost too late already. We waste energy making things we don’t need or even want once we get them home. We’re destroying the planet.”

“Let’s not go into that over dinner. You’re frightening the girls.”

“No she’s not!”

“Lily!”

“Why shouldn’t the girls be part of the discussion? Their generation could save the world. They could save us from ourselves.”

Mom gestures for our dirty dishes and we pass them, surprised when she starts scraping them right there at the table. She never does that. They make an angry sound.

“As fascinating as the book is,“ Jamie continues, “as amazing as the birth process is, our importance is overrated. We’ve messed things up. Mother Earth is polluted, and overpopulated. Her resources can’t support—”

“Stop it!” Mom cries as she picks up the stack of plates and storms out of the room. “I’ve had enough Mother Earth for one night.”

I slump in my chair. Sometimes I think Aunt Jamie is my real mom. Over her shoulder is the china cabinet where my swim-meet ribbons are kept, along with Lauren’s first-through-fourth-grade attendance diplomas, and fragile little things no one’s allowed to dust. Aunt Jamie’s swimming trophies are in there too; Mom’s keeping them for her until she moves out of “that damp little house on the old coast highway.”

I braid the tablecloth fringe until Mom arrives with the dessert tray and coffee.

“Love your bread pudding and hard sauce,” Dad says, wiggling his eyebrows. But when Lauren turns up her nose at it, Dad announces that it’s eight thirty and sends her to bed. “Take the dog,” he adds.

Mrs. Wiggins groans as she struggles to rise up then wobbles across the room. She’ll feel better when we get to the lake tomorrow. Mrs. Wiggins loves Peace Lake.

“Thirty minutes, Lily,” Dad reminds me. “Maybe you’d rather watch TV than listen to all this boring grown-up conversation.”

“No thanks.”

Mom pours coffee. “My God, that dog smells,” she says. “You’d think she was still in the room.”

“Shall we talk about eyebrow mites? Or bed bugs?” Aunt Jamie laughs, taking a sip of wine. “The way they live off us is so smart, so evolved—”

“You’re talkative tonight.” Dad gives her an impatient look. “Feeling the booze?”

Jamie glares at him. “You sound threatened, Paul. Does it hurt to stretch the old cerebral cortex, or are you just being sexist?”

I thought they liked each other.

“Okay you two,” Mom says, clearing her throat. “I appreciate that we’re taking a break from politics for a change, but can we talk about something that isn’t creepy crawly for a while?”

Dad pushes his dessert aside. “Why stop now? We’re just getting started. ” His eyes turn black and deep. “I know. Let’s talk about Frog Boy.”

“Let’s not,” Mom says.

“Frog Boy?” Jamie asks.

“I’m surprised you haven’t . . . Oh, that’s right, you read The Socialist Worker instead of the silly little magazines we do,” Dad says.

“Paul!”

Jamie blushes.

“There were pictures of him in Look.” All eyes are on Dad, who drains the last of his beer before saying, “Frog Boy isn’t man or woman. Or a child. He’s a freak. You can hold him in your hand. Is he happy? How the hell could he be happy? He’s a mistake. He lives in the circus and people stare at him all day. I hope he doesn’t have a brain. I hope he isn’t aware of a damn thing.”

Why is Dad being so mean?

“There are pictures of Frog Boy?” I ask. “Can I see them?”

Dad looks startled to hear my voice. “No,” he answers quietly. “They’ll give you nightmares.” He clears his throat and smiles at Mom. “Great dinner, honey.” He picks at the beer label. “We love you, James, but for a college graduate you’re insufferably naive.”

There’s an uncomfortable silence before all three grown-ups laugh.

I don’t understand. “Maybe Frog Boy likes living in the circus,” I say.

All three grown-ups laugh again. Jamie pats her mouth, and smiles into her napkin. “It’s the wine, Lily. Not you,” she says, taking my hand. Her fingers are cold. Maybe she’s a lizard, with boy and girl chromosomes and a hidden tail, like me. Maybe like Frog Boy too. “Your folks are right. I’m a dreamer.” She smiles at me. “You, however, are something special. You’re an original, a one-of-a-kind without even trying. And a master swimmer to boot.”

“No I’m not.”

But Jamie doesn’t hear me when she touches the pink quartz stone at the center of my crucifix. “Pretty,” she says. “But why do people wear the symbol of Jesus’s death around their neck? Why not His life?”

I’ve wondered too. Maybe I shouldn’t wear it, maybe it makes Jesus sad, maybe it makes everybody sad.

“Blasphemy!” Mom laughs. “You’re lucky Frieda isn’t here.”

Gramma Frieda gave me the necklace. I press it to my chest. “Dad says we make our own luck.”

“Maybe,” Aunt Jamie says, “but I believe that if there is a God, He doesn’t know good fortune from bad, or Jane Russell from Frog Boy. We’re all the same in His eyes, inside and out. All born of the same cosmic gasses, Einstein’s star stuff,” she points at the book, “slime, ether, clusters of cells.” Jamie leans closer and breathes wine stink in my face; usually she smells like Doublemint gum. “Between you and me,” she whispers loudly, “I think Mary and Joseph are crap. The Old Testament too. I’d rather be related to a flatworm.”

“I thought we were,” Dad says. “Unless you’ve given up evolution for something more romantic.” He’s in a good mood again.

The four of us sit quietly together for a while until Dad looks at his watch then leaves the table. A minute later he returns with Jamie’s sweater and satchel.

“Subtle,” she says, scooting her chair back. “Guess I’ve worn out my welcome, huh? Well, somebody had to corrupt the kids, so why not their favorite aunt?”

“Their only aunt,” Dad says, holding out A Child Is Born. “I’m not throwing you out, James. You said you needed to leave before nine, remember? And you’re still an hour from home.”

“Yeah, I forgot. I was having such a good time.”

“Don’t leave your book behind.”

“Keep it for a while. You know, in that fan of magazines on the coffee table: Time, McCall’s, Redbook, explicit photographs of fetuses in utero, Sports Illustrated.”

“No thanks,” Dad smiles.

I touch his arm. “Can’t we borrow it?”

“It isn’t really about s-e-x, Paul. It’s about the wonder of life. All life.”

“You don’t have kids, James. Everything is about s-e-x when you have kids.” He holds out her sweater while she threads her arms through its sleeves. “You okay to drive home?”

She hiccups. “I’m fine. I’m subbing for American Poetry first thing in the morning. Thank goodness it’s community college and freshman level.”

“Dad . . .”

He nearly throws the book at me. “All right already. I don’t want to make it a bigger thing than it is.” He rubs the back of his neck. “Sorry, kiddo, I’m tired.”

Mom gives her sister a hug. When she says something in (what I think is) Romanian, they hug even harder. It’s their secret language.

“Thanks for coming,” Mom says in English.

“Thank you. Everything was yummy.” When Mrs. Wiggins pushes in to sniff Jamie’s pant leg, the old dog wobbles and nearly tips over again. “Poor Wanda Wiggins. I hope she’s staying home tomorrow.”

“Lily wants her to come,” Mom says.

Jamie looks surprised.

“We’ll see,” says Dad.

I still hold the ribbon Jamie made me. She’s smart but Mom’s a better artist.