Читать книгу The Shark Curtain - Chris Scofield - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3

Peace Lake

I leave the ribbon on the dining room table that night; Jamie made it for me so I can’t throw it away. The glitter twinkles, the satin shines. The next morning, when Lauren asks if she can have it, I say yes, but Mom says absolutely not, and sticks it in the china cabinet.

We always stop at Elmer’s Pancake House on the way to Peace Lake, and sit in a booth by the window to keep an eye on Mrs. Wiggins. This year she’s too sick to climb in the front seat, or hang her head out the window, so I don’t see her over Dad’s shoulder when he raises his juice glass in a toast.

“To the master swimmer!” he announces, then winks at me. The people behind us look over their shoulders. I raise my glass too, only my arm’s heavy, like it was at the lake the other day, and I put it down right away.

Mom looks at me. “You already full?” She’s worried that Lauren and I won’t eat enough of the chocolate chip pancakes, fresh bananas, three strips of bacon, and OJ we each ordered. I eat most of it but when I wrap my bacon in a paper napkin to give to Mrs. Wiggins, Mom says no. “It’s too hard on her stomach, Lily.”

Dad didn’t want to bring her, but Lauren and I whined until he gave in. I whined more because Mrs. Wiggins is my best friend, even more than Judy. Dad loves the old dog too; he gave her to Mom on their first Christmas together. I felt terrible when he lifted her in the car this morning and she groaned with pain.

In fact, the longer I sit beside her in the back of the car, the guiltier I feel.

Dad looks at me in the rearview mirror and smiles. “Bet you can’t wait to get your feet wet, huh?”

Yes. No. “How much longer?” I miss my watch.

“About forty minutes.” He clears his throat. “How’s the pooch back there?” Lying between Lauren and me, her giant head is in my lap; my legs are numb.

“Should we pull over so she can wet?” Mom doesn’t like us to say “pee.” She waves her cigarette around the car. It almost covers the bad smell coming from Mrs. Wiggins and her blanket which Mom washes every week, “in its own load.”

“No, no, keep going!” Lauren answers.

Mrs. Wiggins doesn’t want to smell bad. It embarrasses her. She turns a big brown bloodshot eye at me and moans.

* * *

“Did I ever tell you kids how your mother and I fell in love?”

“Yes,” Lauren pretends to be disgusted, “one hundred billion times.”

I start: “Mom was a bathing beauty . . .”

Lauren loves this part. She tells everyone that our mother is the most beautiful mother in Portland, Oregon.

“That’s right,” Dad says. “At a photo shoot at Rooster Rock, modeling swimsuits for Jantzen swimwear. I hadn’t seen her in years. Who would have guessed she didn’t know how to swim? She was made to wear a Jantzen!”

Mom whacks him on the shoulder with a rolled-up magazine. “You’re not exactly Johnny Weissmuller!” she laughs.

Johnny Weissmuller?

“You know, Tarzan? He won five gold medals, girls. Anyway,” Mom explains, “it was the polio scare. Everyone thought that swimming in a lake, even in a pool, could make you sick. You know, Frieda was an excellent swimmer in her day too, and—”

“Mom tripped over you. Right?” Lauren is eager to get on with the story.

“Right, she didn’t see me. She fell for me all right,” Daddy says. “Flat on her face!”

Lauren laughs.

“Just call me Grace,” Mom and I say simultaneously.

Mrs. Wiggins moans.

* * *

Lauren colors, while I listen to the usual joking our parents do on car trips: Mom teases how she should have married “that good-looking Barton boy,” who became head of surgery at St. Francis Memorial Hospital, rather than a “skinny knucklehead.” Dad teases how he never had a girlfriend until he met Mom, or “maybe one, but she was blond and went to Hollywood”; he’s forgotten her name. “Marilyn-something, or something-Mansfield maybe,” he wasn’t sure. He had a French pen pal too, “one of the Bardots, I think,” but they lost touch over the years.

Mom and Jamie rarely talk about growing up in Romania during the war, or what happened to their parents when the girls were sent to live at a Christian school in Bulgaria. Mom will sometimes discuss how Frieda’s church brought them to Portland, and how she and Jamie lived with several families when they got here, even about how they took elocution lessons so “we could fit in,” but usually she just says, “We were lucky,” and changes the topic.

Mom tells one story from “the Old Country,” though. It’s my favorite too, about her dead cousin Albert and how something was wrong with his body, but he still got married, then his new wife ran away during their honeymoon, and he committed suicide. They found him dead in a bathtub.

“With all his clothes on too,” Dad chimes in. “He didn’t cut his wrists. He didn’t drink himself to death. He drowned himself. How the hell do you drown yourself?” He shakes his head sadly. “Whatever drove him to it must have been a god-awful thing.”

“I only met Albert once,” Mom says. “Everyone said he was a funny duck.” Mom called me a funny duck once. “He kept to himself a lot.” Mom says I should make more friends. “Always so serious. Carrying the weight of the world on his back.” Mom says I’m too serious.

“Poor Albert,” she continues, looking in the visor mirror. Lauren turns a page in her coloring book. “I wonder what it was. Maybe,” she winks at me, “maybe he had an extra toe so the army wouldn’t take him. Or maybe . . . an arm growing out of his stomach!” She turns quickly in her seat. “Boo!”

Lauren’s still coloring. Mrs. Wiggins woofs.

I stare. It’s not funny.

“Lily . . .” Mom moans, “I’m teasing.”

“Dummy,” Lauren mumbles. “She’s teeeez-ing.”

I slug her arm, then turn my back to her and open Aunt Jamie’s book and concentrate on seeing a human being in the lumps of blind dough and bug-eyed guppies in each picture. I smile at the pretty pregnant girl in the photographs and wonder if the fetus is healthy. Is it a boy or a girl or a hermaphrodite? Will it have Down syndrome like Aunt Cass? There’s weird stuff in our family and Judy says weird stuff gets passed down. Maybe Cousin Albert had a tail.

When I turn to the eighth week, I gasp.

It’s me, inside out: the single-celled-something-weird that becomes a mud frog, a newt in Mother’s rock garden, a fish, a monkey, or Adam and Eve. At eight weeks and one inch, my heart has been beating for a month. Draped in an egg-white shower curtain, I’m a shrimp, a tiny hunchback with webbed fingers, plastic doll joints and black bullet eyes. My head is stitched together like a baseball. The picture is me on the inside: a fuzzy cashew floating in a starry galaxy.

What happens next month to Lily Elaine Asher of Portland, Oregon, West Coast, United States of America, Northern Hemisphere, Planet Earth, Milky Way Galaxy, in Forever and Ever, amen? Stay tuned, readers!

“Do fetuses have feelings?” I suddenly blurt out. “Do they know right from wrong? I mean, in a fetus kind of way?”

“Did you bring that damn book?” Mom asks impatiently. She lights another cigarette.

“I brought Jules Verne too.”

Dad touches Mom’s shoulder. “You’re the best read kid I know, Lily Lou,” he says. “No. Fetuses are too busy growing and changing to know right from wrong. Their brains are just developing.”

The radio crackles. It’s mostly fuzz except for some guy answering phone calls far away. “I’ll be damned,” Dad says, twisting the dials. “It’s Joe Pine, all the way up here!”

All the way up here and out the car window, Lauren holds up her Brownie Starlight camera and takes blurry snapshots of tall dark trees pressing against each other, crowding out even Bambi. I get dizzy trying to hold my eyes in one place and focus, looking for a path through the dense undergrowth to a hideaway in the bushes.

And wait.

If no one sees me, and I wait as quietly as I can, for as long as I can, something will happen there. Something special. I know it.

* * *

Lauren’s asleep with her hand on the camera when Dad drives around a slow-moving red jeep pulling a matching red rowboat. Jesus waves a bottle of Coke at me from the backseat. He smiles and picks up His tackle box, waving that at me too.

Jesus?

If He’s “always on the job,” like Gramma Frieda says, shouldn’t He be feeding all those starving kids in China?

Okay, so He’s taking the day off, going fishing. Big deal.

“Where’s the funeral?” Dad laughs as he turns into the lane in front of them. Does he see them too?

Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head sit up front, their eyes (and upside-down noses) on the road. I haven’t seen the Potato Heads for a while—Lauren lost most of their eyes, noses, and mouths last year, which is fine with Mom because real potatoes are messy and smell bad after two weeks in my closet. I was experimenting: If potatoes grow underground, they’re used to the dark. How much would they grow in my dark closet? Is water more important or dirt? I was taking notes, even talking to Mr. Alsup (my science teacher) about it.

I keep an ant farm in my closet too. The ants climb to the top, where the clear plastic sky meets the green plastic frame, trying to get closer to God, so He can hear their prayers. Judy says that’s why Asian people build temples high in the mountains. Judy’s family has a miniature Japanese garden, so she knows stuff like that.

Where my bedroom wall meets the ceiling is where my prayers run, like ticker tape, like a locomotive, around and around my room, rattling and smoking, barely making the corners sometimes.

If I were Jesus, I wouldn’t sit in the backseat of the Potato Heads’ jeep. I’d drive instead, and fast. It’s not like it would kill Him.

My parents don’t mention the jeep’s strange passengers. Mom flips down her visor, touches up her lipstick, and checks me out in the mirror. “Lily, are you still looking at Jamie’s book?”

I want to answer, but at eight weeks, one inch, my brain is still developing and I don’t know what to say.

* * *

“Peace Lake!” Daddy announces when his Pontiac rattles onto the gravel road that winds down to the lake basin. Mrs. Wiggins moans and squeezes her eyes shut. She opens them again when we pull in. There are only two cars in the parking lot.

“Great! Nobody’s here,” Dad says, as he unloads the trunk. He hands Lauren the beach towels. Mom tells me to leave my books in the car. Judy says Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea is a boy’s book, but I don’t care. I wish I were Captain Nemo and had my own Nautilus to explore Peace Lake, and then I wouldn’t have to swim.

“Let’s draw, shall we?” Mom hands me her sketchpad and a pencil. “You can draw what you see here at the lake,” she suggests. “Or dinosaurs! Aren’t you studying dinosaurs in school? Just not imaginary scenes from the life of Jesus, okay?”

Gee, I only did that a couple, five or six, times. “Okay,” I mumble, and tuck the pad under my arm. “Thanks.”

While Mom unwraps the blankets swaddling her portable bar, Mrs. Wiggins walks past me to the beach, slower than usual. All of us watch her teeter and stumble through the rocks and driftwood before losing sight of her. We know she has finally reached the water when a flock of noisy ducks fly up and over our heads. A few minutes later she slowly brings me a stick.

Dad’s right, we shouldn’t have brought her.

“She got the stick. Maybe she isn’t as sick as we thought,” Mom says. She looks disappointed. Maybe she wants another pet. Chester, her favorite parakeet, used to sit on her easel while she painted; last year he sipped Mom’s turpentine and died.

“She’s slow,” Dad says, “but she seems to be enjoying herself. She still loves being here.” Lauren laughs when he grabs the kindling ax from the trunk of the car, takes a deep breath, and strikes a pose like Paul Bunyan. “Beware the sharks!” he warns before heading off to collect firewood. Dad always jokes about sharks, in Peace Lake—at the YWCA, even in Lauren’s old wading pool and the bathtub at home; any place there’s water.

“You girls know sharks don’t live in fresh water, right?” Mom asks.

Sure, but I talked to Mrs. Wiggins about it anyway. About Sea Hunt and Crawford Woods and all the dark blurry places I’ve noticed since then, but she just opened an eye and closed it again, reminding me that she’ll protect me and there’s nothing to worry about.

My sister and I pull off our shoes and socks and race across the sharp gravel toward the beach. Lauren runs ahead of me, slowing only to toss back the long lacy vines of the weeping willow where our parents first kissed. They came here on their first “official” date.

Lauren and I fill our pockets with shiny rocks, and stand knee-high in the lake eating barbecue potato chips until Mom yells at us for ruining our appetites.

Minutes later, I sit on a rock with my feet in the water. Mrs. Wiggins lies in the cold sand nearby, panting hard, the stick beside her. “Please, Jesus,” I whisper to my picture of the guy with a halo sitting on the back of a dinosaur, “watch over Mrs. Wiggins.”

Creepy Frank Sinatra sings “Strangers in the Night” on the portable radio Mom placed on the tablecloth, and Dad scoops her up, dancing her to the water’s edge. They walk up the beach hand-in-hand, while Lauren makes drippy sand towers for her sandcastle, and I draw.

Lauren and I eat lunch while they’re gone. There’s no time to waste when you have to wait thirty minutes before going in the water.

Not that I’m going in.

Not that I couldn’t if I wanted to.

Some animals have super-duper hearing. So do I. I try to ignore my parents’ conversation about me. I try to pretend I don’t hear them say that I’ll need “special help” in school if things don’t change. I try not to listen when they say I should see a therapist.

“Stop talking!” I shout, but no one notices except Lauren who yells, “You’ll get cramps!” when I stomp into the lake.

I don’t need a therapist, or special help. All I need is to be left alone. In my own room.

The cold water startles me at first, but I swim out quickly then turn around to face the shore, kicking my feet to keep afloat. The sun is high and hot and dries my shoulders and face instantly. Mom and Dad are back; they sit with Mrs. Wiggins on the sand, looking toward me. Lauren dances with her new pink umbrella.

The water feels good.

I count fifty strokes, divide it by half, swim twenty-five more, cut that in half, and break off midstroke. I was the best at long division; good at making decimals out of remainders too, even if I was sent to the office twice in May for “an overactive imagination.” The first time, I pretended everyone in my classroom was dead so I didn’t have to talk to them. And once, after lunch, I spoke to Miss Pendergrass through a milk straw because it was hard to breathe when I was locked inside Houdini’s steamer trunk. She gave me an F instead of an A on our last spelling test, when my answers were in fake hieroglyphics. I gave her a key to them, and I spelled each word correctly after class, but she still called Mom. When Jamie saw all the watery squiggles and fish shapes I used, she called them “hydro-glyphics.” Hydro means water, she told me. She also told me I was smart, probably even smarter than Miss Pendergrass.

I love to swim.

Maybe it doesn’t matter if I lied to everyone.

When I pass Duck Island, the swampy nesting place Lauren and I looked at through the binoculars, I realize I’m farther out than I’ve ever been. Farther than the swim team, maybe more than halfway across the lake, and I’m tired. If Jamie were here she’d say it was okay that my body is heavy. Just float on your back for a minute. Relax. It wouldn’t matter that my feet tingle like they’re asleep, or that my arms are tingling too. The cold is in my ears and behind my eyes; it’s giving me a headache.

Is the lake punishing me for lying about swimming? Maybe it wants to show me “who’s boss,” like Judy is always threatening to do.

Somewhere around here are the rotted half-submerged pilings of the Floating Doughnut Shack. I wish I were eight weeks and one inch so I could start over again. I wish I could turn back time like some adventurers do in Jules Verne books.

Suddenly I’ve forgotten how to swim.

I roll onto my back but I can’t float forever.

On shore, Mrs. Wiggins paces back and forth in the shallow water. She wades out a little, looks toward me, comes back in, sits down, watches some more, then paces again.

Don’t look, I tell myself, and glance away. I don’t look at Mrs. Wiggins, or my family “rusticating” (Mom’s word for “taking a break from the suburbs”), until Lauren suddenly yells, “Misssss-usssss Wiiiiigg-uunnnssss!”

I roll over and bob in the water. The sick old dog is headed my way, the stick in her mouth.

“No!” I yell. “Go back! No stick, no!” But she keeps coming. Behind her, on the beach, Mom, Dad, and Lauren wave their arms over their heads. I wave back, and Mom puts her hands on her hips.

She won’t make it; I’m out too far.

I hold up my thumb and index finger; Mom’s the size of a circus peanut. I roll on my back again, and kick my feet. At least I think I’m kicking; it’s hard to tell when most of me is numb.

I wish I weren’t a weirdo and a liar, and hadn’t stomped out into the lake when my parents started talking about me. Peace Lake is big; no wonder it’s where Aunt Jamie trains for the Olympic Trials. No wonder everyone clapped for the girls on my swim team. Dad says Jamie and I have the “swimming chops” in the family, but right now I don’t have any chops, and when the sun slips behind a dark cloud, and the water becomes an even colder black soup, I’m more scared than I was when Lauren slipped into the quarry pit.

“Mrs. Wiggins?” I say out loud. When I speak the cold water spills in, filling my mouth, running down my throat, making the rest of me even colder. I try whistling but I can’t. I look for Mrs. Wiggins’s bobbing head in the dark water.

Maybe she went back.

Down in the meadow in a little bitty pool

Swam three little fishies and a mama fishie too . . .

Mom used to sing that song.

“Mom?” I call.

My teeth chatter. Swim back! I tell myself. You can do it! Tell them you’re a dummy and a liar and the lake wants you to apologize. Do it!

Only I stay in place.

Bobbing in place. I’m not going anywhere.

Mrs. Wiggins? Where are you?

On shore Dad wades into the water, waving at me to come in. He points to the sky at the exact moment a bright light flashes. Lightning! Is it close? I listen for thunder, and count out loud like he taught me: “One, one thousand” for every quarter-mile away. “Two, one thousand. Three, one thousand.”

Nothing.

“Stop!” said the mama fishie. “Or you’ll get lost!”

“Lillleeeee!” Mom calls in a scared high-pitched voice. “Hold on! Daddy’s coming!”

Dad runs to the pier where a rowboat is tied. I watch him jump in, pull the rope off the piling, and start rowing toward me. With one paddle. He pauses to search the bottom of the boat for the other, then looks toward me again. One boat, one oar. It’ll take awhile, but he’s coming.

I slip under, but the cold startles me and I pop up again.

So the three little fishies went off on a spree

And they swam and they swam right out to the sea . . .

I’m tired and think of my room, rearrange the books beside my bed, pull out the scrapbooks from underneath, and begin going through each page.

Boop boop dit-tem dat-tem what-tem chu!

Kick kick kick. I’m kicking! I feel it!

Boop boop dit-tem dat-tem . . . kick kick . . .

When I get home I’m adopting one of those little African kids on late-night TV, the ones with flies in their eyes.

The sky tears open.

Brightly lit drops of rain pop and sizzle like the bacon on the grill at Elmer’s this morning. I wish I were there right now, eating chocolate chip pancakes with Lauren. I wish I’d worn the new culottes Mom sewed for me too—bright, flowery ones that match hers and Lauren’s. I wish Mike Nelson, from Sea Hunt, would swim by in his black rubber leotard and save me.

Boop boop, dit-tem dat-tem what-tem chu!

What color was the ribbon Jamie made me?

Purple. Purple?

Am I still kicking? I don’t feel my legs anymore. They don’t tingle, they don’t anything. My arms are empty sleeves that lay limp on the surface of the lake.

I’ve.

Stopped.

Moving.

And they swam . . .

And they swam . . .

I slip under again. My heart is on a trampoline without a spotter.

Is this when you say the Lord’s Prayer for real?

Our Father . . . I can hold my breath for a while, just not as long as Theresa and Carol.

My stomach fills with a thousand macramé knots as I slip underwater. Instantly, my lungs push against my chest. They want out, they want to swim up for air. Numbness is all I feel between the stormy surface and the sandy bottom of Peace Lake.

“Even strong swimmers can drown,” Coach Betty told us.

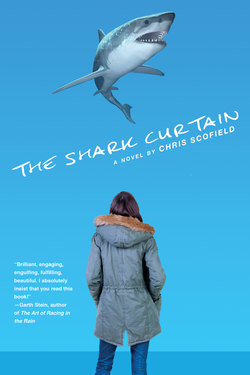

Up ahead is the shark curtain.

“I’m going to die, aren’t I?”

“Nah,” Jesus says, looking up at me from a rusty barrel at the bottom of the lake. “Mrs. Wiggins is dying, not you.” He looks at His bare wrist. It’s half past a freckle. “She’s almost here,” He says, then dissolves like fish flakes in the goldfish bowl back home.

And suddenly, like the Chief Pontiac hood ornament on Dad’s car (or stories of dolphins saving children in Aunt Jamie’s favorite storybooks), Mrs. Wiggins dives for me and I’m face-to-face with her big wet head and bloodshot eyes.

Am I dreaming? Is this really happening?

“Grab my collar,” she says, though it’s hard to understand her with a stick in her mouth. So I do, and pressing myself against her we fly through the shark curtain, through bright stripes of stormy light and warm currents of water until we burst onto the surface of Peace Lake, spitting and coughing.

* * *

Once upon a time . . .

Mrs. Wiggins saved me. I slip my hand out of her collar and we bob on top of the water. Her head is bigger than mine, and with her mouth open, her abscessed gums and rotting teeth, her cancer smell is everywhere. She trembles with cold and pain because the stick is cutting into the corners of the black lips that outline her bloody grin. Three dark teeth stand on their heads, connected to her bottom jaw by a spit-glittered thread of skin. She can’t chew anymore. She hasn’t eaten kibble in a week.

“Give me the stick,” I say, reaching for it.

The old dog pulls away. She’s scared; I see it in her eyes.

“Drop the stick!” I scold, but she doesn’t and starts paddling toward shore. “Wait!” I yell, and somehow muster the strength to lunge at her. She yelps and turns around, flailing at me with her paws, scratching my face and mouth. It’s a blur of water and movement, her legs, my arms, sky, trees, Daddy’s rowboat nearing us. She thinks I’m trying to hold her down, she thinks she’s drowning.

Then it’s over.

I’m breathing, the sun is warm on my face, and Dad is calling “Lil-EEEE!”

My body’s awake. I feel everything, and wave at his boat. “I’m okay!” I shout.

It’s over.

“Mrs. Wiggins?” My heart beats like crazy. The water is still. “Girl?” But she’s quiet and her eyes are glazed. Her mouth stands open, the bloody stick wedged in its corners. Her breath smells like roses, and I remember reading that sainted people smell like roses when they die. A small pool of blood floats between us; in its center is one of her sick teeth.

“Take it,” she says, though it’s still hard to understand her with a stick in her mouth.

“Don’t die,” I sob. “I’m sorry.”

“It’s okay,” she says. But it’s not. Jesus said she was dying, but I killed Mrs. Wiggins. I demanded she come to Peace Lake; I swam out too far.

She bobs a little more, and then tips to one side; the water buoys her. “I’ll take you back,” she says.

“I’m sorry,” I repeat, draping my arms over her. With my chin in her wet thick hair, I clutch her tooth and, looking straight ahead, paddle us toward shore. Panting and crying, we pass Dad who stands up in his rowboat, staring.

Mom and Lauren wait for us on the beach. I see them.

“We’re going to make it!” I tell Mrs. Wiggins. “We’re almost there!” Panting. Kicking. I’m alive. “Mom!” I call. Mrs. Wiggins saved me.

Down in the meadow in a little bitty pool

Swam three little fishies and a mama fishie too . . .

When I’m close enough to see Lauren point at us, I feel a whoosh of energy and know the dog’s scared brave blood is in me now. It slipped into me through one of her cuts, like in werewolf movies, making one blood where there was two; one new person: inside and out.

Mrs. Wiggins and I chase each other around the house, both of us barking, until Mom says to stop. We run like football players, long watery strides, until we fall into the summer grass, exhausted and giggling, Mrs. Wiggins underneath me, chewing on me with her soft gentle mouth.

A final wave pushes us onto the sandy beach, and I throw myself off the old dog and smile up at Lauren and Mom. With the sun behind their heads, their faces are dark, their bodies outlines.

I lay there long enough to run around the house again.

Something’s wrong. “Mom?” I finally ask. She doesn’t move except to cover her mouth with her hand.

I hear a splash behind me. “Lily?” Dad tosses the oar on the sand, and stumbling, exhausted, wades toward Mom.

I see them now. All of them. The rowboat floats away.

Little waves slip under Mrs. Wiggins’s body, rushing in and out of her ears, making her lips flutter like they do when she sticks her head out the car window. I clutch her tooth in my hand.

Lauren shakes. When she cries, “Dummy!” I get goose bumps.

I sit up, take the stick from Mrs. Wiggins’s mouth, and throw it down the beach.

“You killed her!” Lauren cries. The sun lights her hair like a match.

I killed Mrs. Wiggins. I’m a liar and a killer.

When Mom picks up Lauren, she collapses and sobs so deeply Mom’s whole body shakes. Daddy pats my sister’s back, hands her his hanky, and says, “It’s going to be all right. She was an old, sick dog. Everything’s going to be all right.”

Mom spins around. “All right? All right? Are you kidding me?” Her nose flares (like Ferdinand the Bull) when she turns toward me and says, “I guess I was right: we can’t trust you.”

I try to say something but I’m an eight-week-old fetus again.

“For Christ sake, Lily, you almost drowned out there.”

What name does Jesus use when He swears?

Mom jiggles Lauren up and down like a baby. “If you’d come when we called—”

“But I was too far out.”

“That’s exactly the point . . . If you’d listened, Mrs. Wiggins wouldn’t . . .” We all look at the dog covered in sand. Mom turns away first and sets Lauren down. “Why are you doing this to us?”

“What do you mean?”

“Easy, Kit,” Daddy mumbles.

“I’m serious, Paul. I want to know.” She glances at her portable bar. “The doctors don’t know, her teachers don’t know, maybe she knows. Do you know, Lily? What’s wrong with you?”

“Kit!”

“Shut up, Paul.”

My sister and I aren’t allowed to say “shut up.” Lauren sticks her thumb in her mouth; back home, sucking her thumb would cost her a quarter.

Jesus stands in the bushes. Except for the white robe and fishing hat with bright-colored doohickeys all over it, He’s almost invisible in the brush and willows, like a puzzle in Jack and Jill magazine—“Find the Bunnies” in the March issue, “The Pilgrims’ Hats” in November’s.

If I’d died, Frieda would have said He had a plan for me.

“What happened out there?” Mom asks.

“I . . . don’t . . . know,” I say, keeping an eye on the bushes. Tears roll down my cheeks, fat hot salty tears that make me flinch when they race across my scratched face. I feel my tail trying to get out.

“That’s not good enough, Lily.” Mom glances at the bar again. “Don’t you see what you’re doing to this family?”

“That’s enough, Kit.”

I know what happened out there. I know Mrs. Wiggins saved me, not Jesus. Before Jesus evaporated like fish food, He stood up and turned away for a second. When He did I saw a Chatty Cathy pull-string peeking through the back of His robe and seams, where His plastic molds were fitted, running down the back of His arms and legs. When the water lifted His hair I saw what Mom calls root plugs, and a sliver of dark Holy Land skin peeking through the white at the back of His neck.

He’s a doll.

He’s a phony.

Mrs. Wiggins saved me. I close my eyes and press myself against her. “Wiggins wiggins bo biggins,” I cry into her wet coat.

For a minute I’m alone with her on the beach. We live here, just the two of us, and my family only visits when we send them smoke signals, which they can’t read, so they never ever visit, which is fine with us, just fine.

“Banana-fana fo figgins . . .”

When I open my eyes again, Mom kneels beside me. “Oh God, Lily,” she says, “I’m sorry . . . I was so scared. I didn’t know if you were alive or dead, and then the way you . . . and the . . . dog . . . The whole thing is so awful. I shouldn’t have talked to you like that, Lily. Thank God you’re all right, thank God . . .” When Mom touches my shoulder, one of her tears falls on my arm.

In fairy tales, tears change everything.

Lauren stands behind her, her arms crossed on her freckled chest. Her face is red and swollen from crying.

A wave laps the back of my legs. It shifts Mrs. Wiggins a little, making my sister jump. I press a bare foot against the dog’s thick wet body so it won’t move. The cold water washes over my feet, squishing the gritty sand between my toes before it’s sucked into the lake again.

“I hate you!” Lauren suddenly yells, and runs to the weeping willow where our parents first kissed.

Mom rocks me, whispering what sounds like a prayer in Romanian.

Dad sits beside us. After a minute he asks, “Would you like a drink, Kit?”

Mom nods.

I sneeze.

“Bless you,” they both say.

* * *

Later, I sit between Mom’s long tan legs, facing the lake. Her breasts cup the back of my head, and I feel her heart pounding while she combs my hair with her fingers, checking my scalp like she checked Lauren at Crawford Quarry, the way monkeys on TV nature shows check each other for fleas. “Trauma to the head” is Mom’s biggest fear. “Something could be happening in there and we’d never know until it’s too late.”

Dad brings the first aid kit from the car and disinfects my scratches and cuts.

When Mom wraps the dry wool blanket around me even tighter, I realize that she’s forgiven me for killing Mrs. Wiggins.

I can’t forgive myself though. I’ve killed my best friend. I push the sharp end of her tooth into the center of my hand, but it resists going in.

“You okay?” Mom asks.

Yes. No. “Yes,” I whisper.

If Mom and I sit like this until morning, never fall asleep and never move, we could turn back time. Mrs. Wiggins wouldn’t have died, and then, even if nothing were ever right again, Mom would have loved me once, just once, as much as she loves Dad.

“Can you keep a secret, Lily Lou?” She breathes slowly and deeply to keep from crying. I nod and look over my shoulder. Her cheeks are shiny with tears; she’s cried off all her eye makeup. “Sometimes I don’t know what to do,” she says quietly. “Sometimes things happen . . . and I don’t know what to say, or how to fix them. There’s no instruction book, you know. I blurt stuff out without thinking. I hurt your feelings. Or your father’s. I’m not a nice person sometimes.”

“Yes you are,” I say quickly. It hurts to talk and I touch my lips. The salt on my fingers makes it worse.

Up the beach I hear the shovel digging in the sand. Dad and Lauren are burying Mrs. Wiggins.

* * *

When I open my eyes again, the lake is dark, and the sunset skips across the water. Dad has built a fire, and it pops and crackles, sending sweet-smelling sparks into the air. Mom calls them “fireflies.” Her portable bar sits in the sand beside us; the fire highlights the vodka bottle and a half-full plastic cup.

“She was old, and sick,” Mom says. How long have we been talking? The cold penetrates my clothes and wool blanket, and I press myself into her for warmth. “The water, the swimming . . . it was just too much for her.” Mom sniffs. “I know you, and you’ll think about it until you make yourself sick. Listen to me, Lily, okay?” I listen to the waves lap the beach. “It was an accident. Accidents happen, sometimes awful, unfair things happen. Terrible things. You’re too young to take on the world’s heartbreaks. Nobody’s shoulders are that big.”

Mrs. Wiggins?

My embryo tail swells and lengthens, pushing out of me, digging through my skin and clothes, planting me like Mom and Dad’s kissing tree, deep into the beach at Peace Lake.

“Mrs. Wiggins saved me,” I say. I clutch the dogtooth extra tight.

Mom sighs and kisses the top of my head. “I know,” she says, then leans away, reaching for her purse. “Listen, now that you’re awake, I’m going to stretch my legs.” She digs out her cigarettes, stands up, and brushes off her pants.

I watch her walk to the water’s edge and stand there. Even from the back, Mom is beautiful. Prettier than Aunt Jamie, prettier than anyone. “Mom?” I say quietly. I know she can’t hear me.

Dad’s long shadow, carrying the shovel, appears between us. “Doing better?” he asks me.

I want to tell him that lies hurt so much that sometimes you can’t lift a juice glass or swim back to shore, but I don’t, and he tells Lauren to sit with me while he smothers the fire and puts our things in the car.

She sticks out her tongue, begging me to slug her.

So I do.

* * *

It’s dark when we leave Peace Lake. I’m thankful for the headlights that focus my attention on the long, slow drive out of the lake basin.

Dad swerves to miss a dead deer.

“We’re not coming back,” Mother announces. She lights a fresh Kent off the one she hasn’t finished yet. Her hands are shaking.

“What . . . to the lake?” Dad asks.

“Of course to the lake. What else would I be talking about?”

“No, Mom, no,” Lauren whines. “We love Peace Lake. It won’t happen again.”

“Damn right it won’t,” Mom mumbles.

I know I should say something, but I can’t. I’m still in the lake, still staring at Mrs. Wiggins’s milky eyes, still breathing her cancerous breath when she said to me, “You didn’t do anything.”

But I did.

Dad pats Mom’s leg. When she looks at him, he smiles weakly. “I’m serious, Paul. I’m done with this place; it’s dangerous. I should have listened to Jamie when she said the lake was haunted.”

“Haunted? I thought you were the sensible sister.”

“You remember the story about the Indian children drowning when their canoe capsized, don’t you?”

“A cautionary tale, Kit. It’s probably happened in every lake in America.” Mom looks out the window. “No comment, kemo sabe?”

“Lily nearly died out there.”

“Kit . . .”

“No, Paul. We’re not coming back, and that’s that.”

“But Mom, we love the lake!” Lauren cries out. She scowls at me. “You ruin everything,” she says, pinching me. Hard.

“Lauren . . .” Daddy warns. “Kit, listen. You know who should stop coming up here, don’t you? Jamie. Driving four hours twice a week just to swim up here, alone. It’s dangerous. And crazy. Think of the relationships her swimming has cost her. But Lily? Lily just bit off more than she could chew today, that’s all.” He catches my eye in the rearview mirror. “And Mrs. Wiggins did what came natural to her breed. She was a good dog.” He pushes the button on his wristwatch; a small green light briefly colors his face. “It’s been a long day but we’ll be home by ten.”

“Good!” Lauren says.

Jesus races by in the bright red jeep I saw earlier; a raccoon tail waves from the radio antenna. He’s alone this time, and it’s dark, but I know it’s Him. “Woo-hoo!” He yells as He passes, then He really hits the gas.

What happened to the boat? Did He leave Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head tied to a tree and steal their car?

Why didn’t he save Mrs. Wiggins?

Don’t my prayers mean anything?

Mom throws her cigarette butt out the window, checks her lipstick, and snaps back the visor.

“Imagine what the kids will write when they get back to school next week,” Dad chuckles. “‘What I Did on Summer Vacation.’ Let me see, Lauren fell into the quarry pit, Lily nearly drowned . . . and all that in a couple of weeks. Quite a summer.”

* * *

Lauren’s right.

I ruin everything.

Mrs. Wiggins is buried at Peace Lake but her heart, inside the tooth in my pocket, beats all the way home.