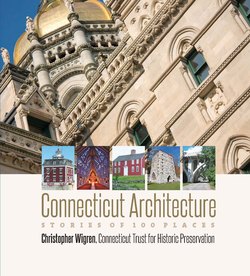

Читать книгу Connecticut Architecture - Christopher Wigren - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

THE FIRST BUILDERS

MOHEGAN HILL, UNCASVILLE

The common image of Native American building in the Northeast is of temporary structures such as the wigwams recorded by English colonists: ephemeral structures of bent saplings covered with bark. However, the modern environmental historian William Cronon has shown that native peoples also shaped the landscape in more wide-ranging ways. They cleared fields for crops, managed woodlands to attract game and make hunting easier, and built weirs to catch fish. Some of the rock piles and stone cellars hidden in Connecticut forests are believed to be Indian structures.

How can traces of the first builders be located today? The Mohegan Congregational Church, on Mohegan Hill in Uncasville, part of the town of Montville, is one starting point. It was established in 1831, at a time when governmental agencies were forcing Indians from their ancestral lands. Building a Christian church demonstrated that the Mohegans had been “civilized” and posed no threat to their white neighbors. The strategy worked. After the Mohegan reservation was broken up in the 1860s, the church was the only property still owned by the tribe and became a focus for Mohegan identity.

The site for the church was chosen for specific, significant reasons. Mohegan Hill had been meaningful to Mohegans long before 1831. All around the church are features important to the tribe, including Moshup’s Rock, bearing an indentation identified as a giant’s footprint; formations where the Makiawisug, or “little people,” lived; and Uncas’s spring, associated with the man who was the leader of the Mohegans when they split from the Pequot tribe in the early 1600s.

In the 1860s Mohegan Hill became the site of the Mohegans’ annual Green Corn festival, an event of spiritual significance revived to cement tribal identity. The festival is a thanksgiving for the harvest and an expression of hospitality to the Mohegans’ neighbors. Tribal members build a large brush arbor, known as the Wigwam (derived from a word meaning “welcome”), in which to serve food and display crafts. This structure gave the celebration its alternate name, the Wigwam Festival. Since 2003 the festival has taken place at Fort Shantok in Montville, another sacred Mohegan site, but Mohegan Hill remains central to the life of the tribe.

Also on the hill is the Tantaquidgeon Indian Museum, established in 1931 by John Tantaquidgeon and his children Harold and Gladys. The small building is constructed of local fieldstone, with arrowheads and stone mortars and pestles embedded in its walls and a diamond-shaped protective symbol on the chimney. Outdoor displays include examples of traditional wigwams and longhouses. The versions of these on view in 2017 were erected in 2011 and reflect current research in historic materials and construction methods.

Remembered, visited, celebrated, and sometimes reinterpreted, Mohegan Hill is central to the tribe’s identity. But although the Mohegans have constructed buildings on the hill and shaped its landscape, its significance is rooted in a different, non-European, concept of place that arises not from human actions but rather from discovering the significance inherent in its natural features. The identification and continued use of places like Mohegan Hill are among the ways in which Native Americans shaped their environment, and should be considered as the first Connecticut architecture.

THE PLACE

MOHEGAN CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH

1831. 1873, remodeled. 1997–2002, restored.

27 Church Lane, Uncasville

TANTAQUIDGEON INDIAN MUSEUM

www.mohegan.nsn.us/heritage

1931, John and Harold Tantaquidgeon. 1957, 1962, additions.

1819 Norwich–New London Turnpike (Connecticut Route 32), Uncasville. Open to the public.

FURTHER READING

Cronon, William. Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. New York: Hill & Wang, 1983.

Fawcett, Melissa Jayne. Medicine Trail: The Life and Lessons of Gladys Tantaquidgeon. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2000.

Lavin, Lucianne. Connecticut’s Indigenous Peoples: What Archaeology, History, and Oral Traditions Teach Us about Their Communities and Cultures. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2013.

FIGURE 59. Wigwam, Green Corn Festival, Mohegan Congregational Church, ca. 1935. Courtesy of the Mohegan Tribe

FIGURE 60. Mohegan Congregational Church. Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation