Читать книгу The House of Serenos - Clementina Caputo - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

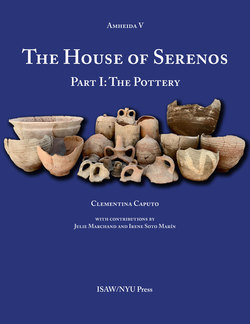

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Amheida is located in the western part of the Dakhla oasis, 3.5 km south of the medieval town of El-Qasr (Figure 1).1 Known in Hellenistic and Roman times as Trimithis, Amheida became a polis by 304 CE, as evidenced by a papyrus from Ismant el-Kharab/Kellis.2 Trimithis in fact served as the major administrative center of the western part of the oasis for the entire fourth century CE.3

The site dates back to as early as the Old Kingdom and was occupied as late as the late fourth century CE. The extension of the visible ruins is approximately 2.5 km north–south and 1 km east–west.4 Two brief exploratory seasons at the site (Amheida: Dakhleh Oasis Project site no. 33/390-L9-1) took place in 1979–1980 by the Dakhleh Oasis Project (DOP), directed by Anthony J. Mills.5 Among other features, the survey revealed several kilns for small-scale production of ceramics dated to the Roman period (Area 1), which have been cleaned and mapped.6 The systematic archaeological excavations at Amheida, which started in 2004,7 have been carried out by an international team under the sponsorship of Columbia University, and since the 2009 season by New York University’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. The project is directed by Roger S. Bagnall (ISAW); the archaeological director is Paola Davoli (University of Salento, Lecce); and the pottery study has been supervised by Pascale Ballet (University of Paris Nanterre).

Archaeologists have so far divided the site into 11 areas (Figure 2),8 four of which are under excavation. Area 1 is characterized both by private houses (so far, only House B2 was excavated in its entirety) and workshops that developed around one of the main streets (S1) of the settlement, and it presents highly diversified pottery, dating from the early Empire to the beginning of Late Antiquity.9 Area 2 is a residential area at the base of the hill that dominates the urban area, characterized by large private decorated houses and public buildings, in which ceramic materials are mainly dated to the fourth century CE. So far, four buildings have been excavated in Area 2: House B1 (Area 2.1); a school of rhetoric and Greek (B5 – Area 2.1); a Late Roman public bath (thermae) (B6 – Area 2.2); and a church (B7 – Area 2.3).10 Area 4, on top of the central hill of the site, shows remains of successive temples with different construction phases dating from the New Kingdom to the Roman Period and a deep stratigraphy that testifies to earlier occupations dating back to the Old Kingdom.11 Area 8 is a densely settled quarter at the northern limits of the city, in which the investigation of a domestic complex (B10) dated to the late third and beginning of the fourth century was undertaken in 2015.12

Most extant written remains from Amheida take the form of inscribed Greek ostraca, although Amheida also preserves hieroglyphic, hieratic, and demotic evidence.13 Among the Greek texts, a group of fourth century documents found in Area 2.1 stands out. It concerns a number of individuals, some of whom were members of the local city council. One of these men, Serenos, was a member of the municipal elite and a Trimithis city councillor, and is associated with the domestic structure designated as House B1 (Figure 3).14 This house, of which the walls are preserved as high as 2.5 m, originally had a square plan (15 x 15 m) and consisted of at least 11 rooms, with a staircase to reach a second floor or the roof-terrace. The two entrances are located on the west street (S3) and the east street (S2), and give access to vestibules (Rooms 7 and 12, respectively), each directly connected to a central space (Room 2), around which all the other rooms are arranged. The main room of the house was a large space (Room 1), entirely plastered and painted with subjects of Greek mythology and scenes depicting the family that owned the house. It is also the only room with a domed roof. Geometric and floral decorative motifs decorated the walls of three other rooms (11, 13, 14), painted with bright colors that are still well preserved.15 At a certain point after 350, the house was enlarged, incorporating the area occupied by a school building (B5) just north of B1. At the time of Serenos’ acquisition or incorporation of B5, some rooms were demolished and others changed their original purpose: e.g., Rooms 9 and 10 were transformed into a courtyard and Room 15 was converted into a storehouse. The house was probably abandoned around or soon after 365 CE.

The excavations below the occupation layers of B1, S2, and S3 also revealed the remains of previous features from the baths, such as a round laconicum (below courtyard 9) and a latrina (below Room 10), which were demolished down to floor level and partly covered by dumped material when the school building (B5) and House B1 were built (Figure 4).16 The change in use of the area occurred, according to ostraca, coins, and other artifacts, not long after the first quarter of the fourth century CE.17

This volume aims to provide a comprehensive study and classification of the ceramic assemblages recovered in House B1 and the two streets (S2 and S3) adjacent to it, as well as in the foundation deposits below them.18 Most of the ceramic fragments found in the area occupied by these features (Area 2.1) were produced in the Dakhla oasis, and more generally in the Great Oasis. Lesser in quantity are the imports from the Nile valley and the Mediterranean. Upon a detailed examination of the pottery, it became evident that the vast majority found above floors in B1, S2, and S3 can be securely dated to the second half of the fourth century CE, thus belonging to the last occupation phase of the area. In contrast, the ceramics accumulated as dumped material below the floors are pre-fourth century in date, and came from dumps in which different kinds of materials were mixed, with objects and sherds dating from predynastic times to the early fourth century CE.19

The main categories of vessels encountered during the analysis of the assemblages in the field are here arranged according to functional and typological criteria.20 Each type is dated by its occurrence in the well-dated stratigraphic contexts, thus making the presence of new types or the disappearance of existing ones readily noticeable. Therefore, comparison with the vessels found in the contemporaneous settlements in Dakhla, and Egypt more broadly, also helped to set the general chronological boundaries for each type, from the end of the first century BCE up to the fourth century CE. Ceramological analysis, along with the evidence of stratigraphy, ostraca, coins, and other objects, allows us to define with more precision the dating range of the various phases of construction and restoration that occurred in House B1.21

1. The medieval town of El-Qasr, dating to the Fatimid period but originating in late antiquity, reached its highest stage of development in the 18th–early 19th century, see Bagnall and Ruffini 2004: 143; Bagnall et al. 2015.

2. P.Kell. I G. 49.1–2 (ή Τριμιθιτών πόλις): Worp 1995. See also Wagner 1987: 190–2.

3. Bagnall and Ruffini 2004: 144; O.Trim. 1.1–2.

4. In general, the site is well preserved, although the strong wind erosion and high humidity (due to its proximity to cultivated areas and spring water) are a threat to the integrity of the buildings made of unbaked bricks. The overall extension of the ruins is still to be determined, obscured by mobile dunes and newly cultivated fields that cover the outer parts of the site: Davoli and Cribiore 2010: 73.

5. Mills 1908: 18–25; Leahy 1980: 331–2; Churcher and Mills 1999. A short visit to the Dakhla Oasis was carried out by H. E. Winlock in 1908, and a series of preliminary investigations were conducted by the Egyptian archaeologist Ahmed Fakhry, whose results were published only in 1982: Winlock 1936; Osing et al. 1982.

6. Hope 1980: 303, 307–11, Pl. XXVII; Hope 1993: 121–7. See also Ballet 2019: 160–1.

7. The topographical survey of the site started in 2001, before the excavation itself, by a Museum of London team (2001–2002) and was continued by the archaeologists from the firm Ar/S Archeosistemi of Reggio Emilia (Italy): Davoli 2015: 61–76. A complete list of reports and publications to date about the work at the site can be found at www.amheida.org; for most of these publications, a downloadable file or a link to on-line open-access publication is provided.

8. See Davoli 2019: 46–80. A first ceramological investigation, made by P. Ballet, J. Marchand, and the author, was made in February 2013 in Area 11 (Caputo 2014: 163–77) and a second prospection (P. Ballet, I. Soto Marín, and the author) took place in February 2014 in Area 6. A short survey of the decorated plaster on walls of several buildings visible from the surface of the site was undertaken in 2015 by S. McFadden, D. Dzierzbicka, B. Norton, E. Ricchi, and A. Sucato: http://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2015.pdf. For the geoarchaeological surveys carried out at Amheida in 2011 and 2013 by a team of geologists, archaeologists, and ceramologists, see Bravard et al. 2016: 305–24; Davoli 2019: 48–53.

9. Boozer 2015. The study of the ceramics found in House B2 (Area 1.3) was carried out by Delphine Dixneuf (2015: 201–80).

10. Davoli and Cribiore 2010: 73–87; Ast and Davoli 2016: 1447–71; Davoli 2012: 267–77; Davoli 2017: 193–220; Davoli 2019: 61–9. Aravecchia et al. 2015: 21–43; Aravecchia 2018. For a preliminary study of the ceramic materials found in B1, see Caputo, Marchand, and Soto 2017: 1011–26.

11. Davoli and Kaper 2006: 12–14; Davoli 2012: 263–7; Davoli 2015: 35–42 and 57–60; Kaper 2015: 42–56.

12. Because of security restrictions, it was not possible to have field seasons since 2016; thus it cannot be predicted when it will be possible to continue the work on House B10. For a preliminary study of the context, ostraca, and ceramic assemblage collected from the house, see Bagnall et al. 2017: 195–211.

13. Cribiore, Davoli, and Ratzan 2008: 170–91; Cribiore and Davoli 2013: 1–14; Cribiore 2015a: 179–92; O.Trim. 1; Vittmann 2017: 491–503. For the study of the material aspects of the ostraca of Amheida see Caputo 2016: 62–88.

14. O.Trim. 2: 95–102.

15. McFadden 2015: 193–212; McFadden 2019: 281–96. See also Schulz 2015: 23–6.

16. Davoli 2017: 202–4.

17. O.Trim. 2; Ast and Davoli 2016: 1447–71.

18. An assemblage has been defined as all the ceramic vessels from the occupation layers of a single building or street, assuming that the scatter pattern of ceramic fragments is mostly confined to that location.

19. Ast and Davoli 2016: 1447–71.

20. I would like to thank my colleagues Irene Soto Marín and Julie Marchand for their help in the ceramic quantification on the field. The pottery from Area 2.1 was sorted on site and recorded also by other ceramicists, such as Gillian Pyke (2005–2006 seasons), Delphine Dixneuf (2007–2009 seasons), and Andrea Myers Achi (2008–2011 seasons).

21. The present study does not include the oil lamps that have been found in the house of Serenos because they have been considered as small finds. The small finds and coins found in the same contexts of the house are under study and will be part of another volume.