Читать книгу The House of Serenos - Clementina Caputo - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

METHODOLOGICAL APPROACHES

This chapter is devoted to the description of the excavation methodology and the post-excavation analysis of the contexts and the ceramic finds from House B1, Street 2, and Street 3, to facilitate the understanding of the relation between the ceramic materials and their archaeological contexts.

Excavation at Amheida is based on the stratigraphic method.1 Stratigraphic units have been distinguished according to their formation processes and described either as Deposition Stratigraphic Units (DSU), which are layers or strata, and Feature Stratigraphic Units (FSU), such as floors, walls, pits, ovens, cuts, etc. All the units are identified by a number that is unique within each archaeological area or sub-area.2 Amheida is divided into eleven different “Areas” (Area 1, 2, 3, etc.), each corresponding to a section of the settlement characterized by its location, architectural characteristics, and other notable features. Within each area are sub-areas (sub-area 1.1, 1.2, 2.1, 2.2, etc.) that are generally predefined and recognizable spaces (buildings, streets, etc.). We refer to buildings by using B followed by a number (e.g., B1, B5, etc.), and to streets by using S followed by a number (e.g., S2, S3, etc.).

All finds are recorded daily on Stratigraphic Unit Quantitative (SUQ) data forms. Once a stratigraphic unit is completely excavated, a final SUQ form is filled out to summarize all the daily sheets. The final SUQ is useful, as it gives a general overview of what has been found in each stratigraphic unit. The weight (kg) and the quantity (no.) of all the objects, ceramic fragments, and fabrics are entered into the form, sorted according to the reliability of the archaeological context in which they were found (secure versus insecure contexts).3

All diagnostic and recognizable objects are individually recorded on Find Record forms, where they are identified by an Inventory Code. The Inventory Code consists of the initial of the site (A = Amheida), the year in which the find was recovered, the number of area/sub-area, and the stratigraphic unit from which the artifact came, followed by a unique, progressive number assigned by the recorder (e.g., A07/2.1/243/12054). This form contains the description of the object, the category to which it belongs, the maximum dimensions of the piece expressed in centimeters, the material, the manufacturing technique, and the state of preservation. Each Find Record form is accompanied by a digital color image of the object and in some cases by a drawing in 1:1, 1:2, or 1:5 scale.4

All forms (DSU, FSU, SUQ, and Find Record) are entered into the project’s official online database.5 This important tool allows us to relate every find back to its archaeological context, as well as perform searches and generate statistics.

1.1. QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS AND CERAMICS PROCESSING

The general methodology applied to the quantification analysis of ceramic materials consists of two main steps. The first takes place in the field and consists of sorting the ceramic fragments found in each stratigraphic unit. Sherds found in secure contexts are divided according to fabrics and wares and are analyzed in detail.6 Each fabric group is weighed, the sherds are counted, and the information is recorded on the SUQ form. Rims, bases, and handles are also counted separately and recorded according to their typology. Body sherds are generally discarded unless they can be re-joined or belong to a stratigraphically relevant unit, in which case all pottery is kept. For non-secure contexts, only diagnostic sherds and body sherds from unknown fabrics or with notable characteristics are recorded on the SUQ form and kept for further studies.

The second step consists of the systematic quantification of the fragments collected for each context and stratigraphic unit, so as to determine the Minimum Number of Individuals (MNI),7 followed by a selection of the most representative shapes and fabrics to establish the main typologies and update the Site Shape Catalogue (SSC), which is the main tool for working in the field. All the diagnostic sherds, i.e., rims, bases, and handles, from each unit are recorded on the Fiche de Comptage where the profile sketch of the sherd is also traced, along with the fabric/ware code and the type number from SSC.8 Unknown fabrics and variants are fully described. The Site Shape Catalogue is built year after year for each excavation area and is intended to collect all the vessel shapes found, to which a code number is given. This system allowed us to avoid drawing all of the diagnostic pieces found in the same area, an efficiency of some importance given the very high number of sherds present at Amheida. Only new types or special cases, as well as complete vessels, are individually documented and described in Find Record forms, with a new Inventory Code assigned to them. These vessels and fragments are drawn,9 photographed, and entered into the SSC with a type progressive number, in order to keep the catalogue constantly updated. The types are arranged in the SSC according to the functional class and shape (bowls, plates, kraters, pots, etc.), and further subdivided according to their morphological parameters (characteristics and diameter of the rim, base, handle, and body).10 The fabric and ware, as well as the manufacturing techniques, also play an important role in classification.

The information comprised in the Find Record form for each type follows the general criteria for cataloguing archaeological finds.11 The surface treatment (slip, pseudo-slip, decorations, etc.), traces of use (e.g., soot), dimensions (diameter of the rim and/or base, wall thickness, height of the vessel), manufacturing techniques (on the wheel, hand-modelled, molded, etc.), and state of preservation (complete, not complete, fragmentary, good, fair, bad) are also indicated.

The macroscopic analysis of the fabric is performed through the use of a monocular magnifying lens.12 This instrument, although far less precise than petrographic and physical-chemical analyses, is a sufficient tool to identify ceramic fabrics directly in the field. The macroscopic study of all ceramic sherds followed these criteria:

• Surface and fracture color of the fabric;

• Hardness;

• Appearance and mineralogical composition of the clay (i.e., color, size, occurrence, and quality of inclusions);

• The final processing (firing modes), surface treatment (i.e., slip, decoration, etc.), and eventual decoration.

In describing a vessel, the color of the fracture is usually provided (i.e., beige, light pink, orange, red, reddish/brown, brown, gray, black, and greenish), as well as the color of the core, if different from the surface (pinkish, reddish; gray, gray/blue). The Nile and ferruginous clays are rich in degreasing (straw, sand, quartz, mica) and melting (limestone, iron oxide, feldspar) additives. Chaff and sand inclusions are present in large quantities, especially in the fabrics characteristic of large storage containers (jars, pithoi) and vessels of domestic use (basins and baking trays). A relevant amount of micaceous inclusions is frequent mainly in the fabrics characteristic of amphorae, in particular in the Late Roman Amphora 7, which typically exhibit grains of mica golden in color and uniformly distributed. The ceramic fabrics in the oasis contain a significant amount of calcareous and iron oxide inclusions. These components result in the vessels presenting surface colors ranging from red-orange to purple, markedly lighter than the traditional productions in Nile clay that are red-brown to brown in color. Medium- to large-sized red and black inclusions are clearly visible in the fracture of vessels produced in calcareous clay, such as jugs and bowls.

The hardness is defined by the vessel’s scratch resistance, determined by the compactness of the clay or by the type and number of particles present inside the fabrics.13 The ceramic body is defined as:

1. Hard or very hard, when scratchable only by a metal tip;

2. Pliable or soft, when scratchable by a fingernail;

3. Brittle, when flakable by finger pressure.

The size of the grain and the amount of inclusions are defined as:

1. Purified — devoid of inclusions visible to the naked eye;

2. Fine — rare, very fine inclusions (0.1–0.2 mm);

3. Medium-fine — contains fine inclusions (0.3–0.4 mm);

4. Medium — medium sized inclusions visible to the naked eye (ca. 0.5 mm);

5. Medium-coarse — grain size ranging from 0.5 to 1 mm;

6. Coarse — medium to large inclusions (1 to 3 mm).

The combination of these characteristics is at the basis of the classification of the fabrics.

1.2. FABRICS

The fabric identifications utilized in this study are based on the Dakhleh Oasis Fabric System, originally developed by C. A. Hope during the survey phase of the DOP Project.14 Each fabric type has been provided with an identification code according to this system (Table 1 below). The benefit of using this system is that it enables material recorded prior to the current study to be more easily incorporated, while also allowing comparisons to be made with previously published studies. However, the description and understanding of relationships between the various fabric groups have been improved thanks to the recent publications on Ptolemaic ceramic in the Dakhla oasis and Western desert by James C. R. Gill,15 the petrographic analyses conducted by Mark A. J. Eccleston,16 and additional observation arising from conversations in the field between the author and Pascale Ballet.

Among the ceramic material found at Amheida, the most common fabrics in Area 2.1, and on the site in general, are A1 and A2, while variants of these fabrics are utilized in much smaller quantities (A5, A28). A smaller quantity of vessels is made in marl fabrics (B1/B10/B15).17 A11 is a fine kaolinitic, iron-rich, brittle fabric used for manufacturing thin-walled and ribbed cooking jars, casseroles, and bowls, and it is very common in Late Antique contexts. Known as “Christian Brittle Ware,” it is possibly made of a local kaolinitic clay,18 and is well attested in Area 2.1, in the DSUs above floor levels dated to the fourth century CE.19 A thicker variant of A11, known as B17, is possibly a precursor (mid-third century CE) to the thinner-walled fabric A11 of the fourth century.20 Few types of bowls and cooking pots made of B17 are attested in the DSUs below the floors (pre-fourth century). The vessels intended for domestic use, such as storage vessels/pithoi, basins, trays, and molds, as well as some specialized forms, are characterized by a medium coarse-textured fabric, rich in vegetal temper (A4). Fairly common in the Dakhla oasis, this fabric is attested since the Old Kingdom.21

Alongside the regional iron-rich and calcium-rich productions, other fabrics (B3b=B3 and A27) commonly attested in Dakhla and Kharga oases have been identified. Their places of manufacture are still uncertain or unknown, and for this reason they are generally defined as productions of the Great Oasis. They correspond to two regional productions that, during the fourth century CE, are usually attested in both oases and they are associated, respectively, with the group of the Yellow Slipped Ware and the group of fine Red Slip Ware.

The fabric B3b has recently been assimilated in Gill’s study on Ptolemaic productions in Dakhla oasis and Western Desert to fabric B3, because it has been shown that its composition is unrelated to B3a.22 At Amheida (Area 2.1), B3 (previous B3b) is associated with a specific production consisting of Double-handled bottles/flasks and small bowls with yellow slipped surfaces. Their manufacture is mainly attested in the Kharga Oasis (specially in the North) from the fourth to the early fifth century CE.23

The second fabric (A27) was used for vessels with shiny-red slipped surfaces that imitate the productions in North African Terra Sigillata (African Red Slip Ware).24 Generally, there are three main categories produced in this technique: ceramic tableware, terracotta figurines, and oil lamps. Examples belonging to this family of wares were found in large quantities at the fortified settlement of Douch/Kysis and ‘Ain Shams in the Kharga Oasis. For this reason, Rodziewicz has termed this fabric Kharga Red Slip Ware.25 The same fabric and shapes have been identified by Hope in the Dakhla oasis, especially at Amheida, Ismant el-Kharab/Kellis, and Mut el-Kharab, initially as “material of the Christian Period” and later named Oasis Red Slip Ware.26 So far, the production centers have not been identified in either Oasis.27 The A27 fabric ranges from red/brown to light red in color with a quite dense body, rich in silica and iron oxides.28 The surfaces have a thick shiny-red slip, frequently burnished; decoration is not common.29 The vessels produced in this fabric and belonging to the family of the Oasis Red Slip Ware are found in contexts dated from the fourth to fifth centuries CE.30

Imports from the Nile Valley found in Area 2.1 consist mainly of wine amphorae Late Roman Amphora 7 and a few fragments related to small containers for liquids, mostly table amphorae. A few fragments of Rhodian amphora and Amphore Égyptienne 4 have been found in some strata pre-dating B1 and Street 2.31

1.3. WARES

Wares can be divided into families on the basis of the presence or absence of a surface coating and its color (Table 1 below). Each type of surface treatment can support further decoration in the form of painted designs, polish or burnish. In this study, the term “slip” refers to a coating that has been applied prior to firing.32

Ceramic coating increases the degree of impermeability of the body and helps to smooth the roughness of surfaces. The most frequent type of coating used for the ceramic materials from Area 2.1 is the “clay or mud” slip, obtained by immersing the pot, before firing it, into a liquefied suspension of clay particles in water. The color of the slip varies depending on the firing method, the nature of the clays, and the pigments used, if any.33 Generally, the slip of the vessels produced in ferruginous clay (Group A) ranges in color from orange to dark red. Usually, the shiny red color is due to the addition of red ochre clay34 or the use of iron-rich clay combined with an oxidant firing environment.35 The light slip, from white to cream to pale yellow, may be associated with both ferruginous and calcareous clay (Group B) products. The slip on the surfaces of vessels produced in Nile clay is reminiscent of a fine white wrap (white wash) applied by spraying on the exterior surface of the containers.36

The term “pseudo-slip” is rarely used in this study. It typically refers to a surface coating obtained by using the same clay as that of the vessel. During the modeling of the clay on the wheel, the repeated passages of the potter’s hands on the artifact polish the surface, bringing to the surface the finer clay components present in the doughs.37 The distinction between slip and pseudo-slip is difficult to define when the color of the ceramic body is the same as the coating, as in the case of products in calcareous or marl clays.

The following coding is employed to indicate the type of ware:38

• P = plain or uncoated

• S = slipped or coated

• W = washed

• D = decorated

• b = black

• br = brown

• c = cream

• o = orange

• p = pinkish

• r = red

• w = white

• y = yellow

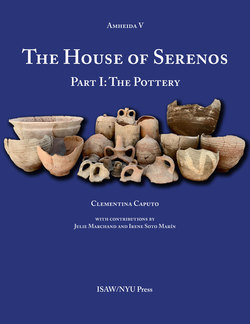

All the fabrics and wares are summarized in the following Table 1. The macro-Photo of the fracture of some of the fabrics is showed in Figure 5. A graph illustrating the incidence, in terms of kilograms, of the fabric from the contexts above floors B1, S2, and S3, is provided in Table 2.39

Table 1. Fabric and ware descriptions

| Coarse Ferruginous Fabrics | |

| Fabric: A1 Wares: P, Pb, Sc, Sr, Sr/o, Sw, Dc, Dr | Medium to coarse textured fabric; medium-bodied. The inclusions characterizing this group vary in size and quantity, according to the fine quality of the fabric. Macroscopically, they include sand, limestone, and chaff, of varying size and quantities, as well as rare clay granules, platey shale,1 and grog.2 This fabric is fired red to brown/orange (A1a) to gray/black (A1b). The fracture is often zoned: brown/orange exterior layers with gray/black core. This is the most common fabric in the Dakhla oasis throughout all historical periods, and it is used for an extensive range of shapes (storage and transport containers, cooking ware, and table ware). |

| Fabric: A2 Wares: P, Sc, Dc, Dr | Fine to medium textured fabric; dense-bodied and hard. The distinction between the fabrics classified as A1 and A2 is based on the higher proportion of finer inclusions. In general, A2 has a finer groundmass.3 Like A1, this fabric is fired red to brown/orange (A2a) to gray/black (A2b). Zoned fracture is less common than A1: the core is usually thin and well defined, gray to brown/gray in color. Compared to A1, this fabric is used in a more limited range of shapes (short-necked jars, kegs, flasks, and kraters). |

| Fabric: A5 Wares: Sc, Sr, Sw, Db, Dr | Medium-bodied, medium-coarse textured fabric. Macroscopically visible inclusions consist of large amounts of quartz, clay pellets, and limestone (green/yellow vacuoles of different sizes are visible on the entire surface). Quartz/sand-rich variant of A1.4 The fabric appears to be over-fired purple-brown to gray in color, without a clear zoning.5 The surface has often a thick white or cream slip, sometimes red. Decorations are more frequent on the Roman jars and consist of black or dark red designs. Fabric A5 is used primarily in handled filter jugs and storage jars with foot ring, usually decorated. |

| Fabric: A28 Wares: P, Sc, So, Sr | Medium to open-bodied, medium coarse-textured fabric. Macroscopically visible inclusions consist of sand and limestone, and less frequently of clay pellets. It is a limestone-rich variant of A1/A2, which has been low-fired.6 This fabric is fired mid-brown with no clear zoning. Fabric A28 occurs rarely within the corpus and the range of forms is relatively limited. |

| Mudstone/Claystone/Shale Fabrics | |

| Fabric: A11 Wares: Pb, Sr, Dc, Dr | A dense-bodied, kaolinitic brittle fabric characterized by a hard core and medium-fine texture. Medium scatters of small calcareous inclusions, dark red and sometimes black particles are visible. Known also as Christian Brittle Wares. It was fired in a variety of colors: light surfaces usually have regular bluish-gray cores (mode A), while dark surfaces have cores ranging from pale orange to pink (mode B). The inclusions consist of very fine red (hematite) and black (plates of silica clay) particles of different sizes, fine grains of quartz, very fine shale particles, and rare very fine white inclusions. This fabric is used in Area 2.1 for thin-walled cooking jars, casseroles, and bowls, with a red and cream coating, sometimes decorated in red dots on cream bands, mainly dated by archaeological contexts to the late 3rd and 4th centuries CE |

| Fabric: B3 (previous B3b) Wares: Sc, Sy, Dr | Medium-bodied, medium-fine to medium-coarse textured fabric. The inclusions mainly consist of medium and fine red particles, sand, and a moderate presence of small shale plates and clay pellets.7 The fabric is usually fired orange/pink or yellow/brown. The surface has often a thick yellow/creamy slip with spiral and waves decorations. Fabric B3 is used in Double-handled cylindrical bottles/flasks and small bowls. |

| Fabric: A27 Wares: Sr, So | A dense-bodied fabric, fine to medium-fine texture, rich in silica and iron oxides. Macroscopically visible inclusions consist of numerous fine grains of quartz, very fine white and black particles, and small plates of clay ovoid in shape (plaquettes d’argile silicifiée). The fracture ranges from red/brown to light red in color, dark colored cores are rare; the surfaces have thick shiny red/orange slip. This fabric, characteristic of the fine ware of the fourth and fifth centuries CE (Oasis Red Slip Ware = Kharga Red Slip Ware), is associated mostly with open forms such as bowls and dishes, some juglets, as well as lamps and terracotta figurines. |

| Mudstone/Claystone/Shale Fabrics—Vegetal Tempered Variant | |

| Fabric: A4 Wares: Sr, Sw, Ww | A medium to open-bodied, coarse-textured fabric. It is characterized by the presence of many long planar voids, which are the results of straw and other vegetal material being burnt away during firing. Macroscopically visible inclusions consist of sand, limestone, clay pellets, and in the occasional low-fired example it is possible to detect the remains of straw.1 This fabric is fired reddish to brown to gray/black, usually zoned with dark gray/black core, apparently caused by the burning out of the vegetal temper.2 The surfaces are usually not smooth or homogeneous in color. This fabric is almost exclusively used for domestic vessels with very thick walls, such as bread molds, baking trays, pithoi, and large basins. |

| Coarse Quartz Marl Fabrics | |

| Fabric: B1/B10/B15 Wares: Sc, Sw | An open-bodied, medium to coarse textured fabric, with many small rounded voids. Macroscopically visible inclusions consist of fine quartz, rare fine clay pellets and fine shale.3 This fabric is usually fired cream to gray/green, although pink is sometimes found. It is occasionally zoned, with cream interior and exterior surfaces and a gray/green or pink core. It generally has a soft, lightweight consistency and is usually quite brittle. This fabric is generally used for liquid containers (water jugs and costrels), lids used also as bowls, and small bowls stricto sensu. |

| Imports4 | |

| Fabric: A3b Wares: Sbr, Pr/br | Nile Silt fabric is attested only in few examples in the corpus. The vessels made in this fabric are typically fired a dark “chocolate” brown and stand in contrast to the typical Oasis fabrics, which are never fired in this color. The Nile Silt imports also display a finer, dense, texture with minimal macroscopically visible inclusions. The presence of mica is a clear indicator that this fabric is imported, as mica does not occur naturally in the Oasis. The Nile Silt fabric is associated to wine amphorae (LRA 7 and AE3), small table amphorae, bottles. |

| Lake Mariout fabric Ware: Sr/br | Fairly coarse sandy and rough fabric, reddish-brown in color (7.5 YR 7/8). Macroscopically visible inclusions consist of frequent grains of quartz, some limestone, particles of mica, and fine small iron oxide. Light reddish/brown slipped surfaces (2.5 YR 6/6). Lake Mariout fabric is characteristic of the Amphores Égyptiennes 4 (Egyptian Dressel 2/4). |

| Rhodian fabric 15 | Hard, fairly fine fabric, pale orange in color (5YR 7/6) with a paler slip on the outer surface. Macroscopically visible inclusions consist of sparsely rounded white inclusions, sub-rounded and rounded red-brown particles, sparse quartz and black iron-rich inclusions. |

Table 2. Total kilograms for each fabric found in B1, S2, and S3 (above floors)

1.4. MANUFACTURING TECHNIQUES

The majority of the containers present in the ceramic corpus of Area 2.1 are wheel-made. However, in the preparation of the handles for cooking pots, jugs, and amphorae, potters frequently used the freehand modelling technique. In the case of storage amphorae, the toes are molded by the potter by a torsion of the excess clay at the base of the amphora.

The coiling techniques or clay plates are reserved mainly to the manufacture of large vessels with thick and/or taller walls, such as pithoi, baking trays, and bread molds.40

Apart from the category of lamps, which is not discussed in this volume, only one category of ceramic has been molded, that is the one consisting of the red slipped vessels made of A27 fabric (ORSW).41

1.5. DATING OF THE CERAMICS IN AREA 2.1

The stratigraphy in Area 2.1 is articulated into four main distinct horizons: the earlier phase (Phase I), with a large public bath occupying the area in which stood Serenos’ house (B1), the school (B5), and, later, the bath to the north (B6), was founded on natural, compacted sand dunes and abandoned toward the end of the third century CE or perhaps somewhat earlier.42 The ruins of the bath were razed and covered with dumped materials onto which B1 and B5 were subsequently built in the second quarter of the fourth century CE (Phase II). The phases of use of B1 (Phase III) have been identified in the restorations of walls, floors, and paintings, but little securely datable material has been found in connection with these phases, which belong approximately to the period 335/340-365/370. The post abandonment phase is identified with some refuse found in the DSUs above the floors in B1, S2, and S3 (Phase IV).43

The study of the ceramic assemblages from this area, according to the stratigraphy,44 complements the analysis of the numerous dated ostraca found in both the dump layers (ca. 275–350 CE) and occupation levels (ca. 350–370 CE),45 the coins (337–361 CE),46 and other objects,47 contributing to a more refined interpretation of the archaeological contexts. In general, the deposits of dumped materials found in the foundations of B1, S2, and S3 have provided ceramic types dated between the end of the first century BCE and the beginning of the fourth century CE. The occupation deposits in B1, S2, and S3, on the other hand, yielded an abundant quantity of pottery dated to the second half of the fourth century CE onwards. To the post-abandonment period of the buildings in Area 2.1 belong those ceramic types that appear sporadically in the units lying directly above the floor deposits and that can be assigned to a period after 370 CE onward.

Each type in the catalogue of this volume has been dated by taking into consideration a number of factors, including stratigraphic sequence, DSU formation process, and the type’s incidence or absence in the ceramic assemblages coming from the reliable stratigraphic units. Comparisons with wares and shapes attested at other sites also serve as important data. Parallels with vessels found in contemporaneous sites of the western Oasis, as well as elsewhere in Egypt, help to define each production’s chronological horizon. The suggested dates published for these comparanda are provided in the Catalogue.

1.6. STRUCTURE OF THE CATALOGUE

In order to deliver a synthetic yet analytical overview of the ceramic material, this volume adopts a typo-chronological classification based on a selection of the individual objects found within the most significant contexts in occupation levels and in the dumped layers below House B1 in Area 2.1 (Chapters 2 and 3) and whose classification principles will be explained below. I have based the study on the stratigraphic analysis and interpretation of Area 2.1 made by Paola Davoli, which will be published in Amheida VI. Furthermore, a detailed description of some selected contexts and the quantification of the vessel types illustrating the ceramic assemblages for the most reliable stratigraphic units is also provided (Chapters 4 and 5). The number assigned to each type in the catalogue is also used as a reference number for similar shapes whenever they appear in the analyzed contexts.

The Catalogue for Area 2.1 is arranged according to functional categories, such as table and service wares used for serving and consumption; utility wares used to prepare food; cooking wares; and storage and transport vessels. Two additional categories include (a) imports from the Nile Valley and the Mediterranean48 and (b) miscellanea. The vessels within each functional category (bowls, dishes, basins, kraters, pots, casseroles, etc.) are classified by type-groups (Group 1, Group 2, etc.) according to the morphological characteristics, and further divided into sub-groups (Group 1a, Group 1b, etc.) according to the variants within each group. In Chapter 2, an analysis of the major categories comprising the corpus is provided by types and is chronologically arranged. The emphasis is on shapes that are encountered frequently within the contexts; rare forms are also included if they were found in well-dated contexts or if they have parallels from other sites. Observations about the possible function or use of particular shapes are indicated when possible. The Catalogue illustrates the most complete or well-preserved examples for each shape found in the whole sequence of stratigraphic units in Area 2.1. Fragmentary vessels are included if they are particularly common or unique.

Each record in the Catalogue (Chapter 3) consists of the following fields:

No.: Progressive Catalogue Number.

Inv.: Inventory Number assigned during the recording phase.

SSC: Site Shape Catalogue number.

Context: Type (Room, Street, etc.) and stratigraphic unit (DSU, FSU, etc.).

Fabric/Ware: Reference code number of the ceramic material, based on the table included in this chapter.

Dimensions: Main measurements of the fragment expressed in centimeters (cm).

Description: Morphological characteristics of the vessel, surface treatments, decoration, evidence of use.

Parallels: Bibliographic references and range of dates for similar types attested in comparative sites.

Phase-date: The date range of the type, based on the context(s) in which it was found at Amheida (Area 2.1).49

Phase I: Imperial thermae (B3, including B6).

Phase II: Destruction and levelling with waste and debris of part of the thermae (B3).

Phase III: Private houses on the levelled yard.

III.1 – Construction of B1, B8, B5, S2, S3 (around 340 CE).

III.2 – Restoration and restyling.

III.3 – Restoration.

III.4 – Abandonment (around 370 CE).

Phase IV: Post-abandonment (after 370 CE onward).

1. Eugene Ball employed the Locus Lot Method in 2004. In 2005, the stratigraphic method was introduced by the new archaeological director, P. Davoli. See Davoli (forthcoming), Amheida VI: The House of Serenos. Part II: Archaeological Report. See also Harris 1989; Roskam 2001.

2. A general plan is drawn up for each stratigraphic unit, usually in 1:50 scale, showing the unit’s outline, position, and elevations. Sections and any other relevant details of the unit are instead drawn in 1:10 or 1:20 scale, when necessary. A high quality digital photograph is included in the graphic documentation. Area/sub-area and stratigraphic unit numbers are always noted on all records, object drawings, and labels.

3. The Deposition Stratigraphic Unit (DSU) is reliable or secure only when it is sealed and has not been disturbed in recent times. Surface DSUs are not reliable, nor are DSUs close to the surface unless they were sealed by a collapse of some extension. In our specific case, we can consider as secure contexts only those units directly above floors that were covered by the collapse of the ceiling or by windblown sand, which preserved the last occupation and the post-abandonment deposits. The reliability of a DSU can be discerned in the field during its excavation and during the study of the materials present in the DSU.

4. On the subject of archaeological drawings, see Leonardi and Penello 1991: 18–41, 41–72. See also Manzelli 1997: 181–9; Mascione and Luna 2007: 87–99.

5. Available at www.amheida.net. The database has been created and implemented by the Mission’s official IT Engineer, Bruno Bazzani.

6. The term “fabric” refers to the type of clay used for manufacturing the vessels. The term “ware” refers to an identified tradition of how a fabric is used to produce vessels with consistent characteristics. These characteristics can include how the fabric is processed before it is used to form vessels; the addition of tempers; surface treatments, such as careful finishing or the application of slips; and the control of the kiln conditions to create a consistency throughout the production tradition.

7. The principle of Minimum Number of Individuals consists of estimating the number of individual vessels present in each stratigraphic unit. If a shape is represented by n rims and n + 1 bases, the number of rims is the one indicating the value of MNI. For the methods of ceramic quantification see: Arthur and Ricci 1981: 125–8; Arcelin and Tuffreau-Libre 1998; Raux 1998: 11–16; Hesnard 1998: 17–22; Anastasio 2007: 36–8.

8. For the fabric classification system used at Amheida, see the paragraphs “Fabrics” and “Wares” in this chapter.

9. The ceramic drawings in this volume have been made and digitized (Adobe Illustrator) during the several excavation seasons by the author, Julie Marchand, Paola Vertuani, and Stefania Alfarano.

10. On the ceramic typological classification methods, see: Gardin 1985; Anastasio 2007: 33–6.

11. Rigoir and Rigor 1968: 327–34; Parise Badoni and Ruggeri Giove 1984; Ruggeri 1993; Mancinelli 2016.

12. Lens with resolving power 20x and field of view of 21 mm.

13. About the hardness, see Cuomo di Caprio 2007: 73–4 and 642–3.

14. Hope divided the Oasis fabrics into two broad groups: iron-rich or ferruginous fabrics (A-group), and calcium-rich or marl-like fabrics (B-group), each with further sub-divisions. For the fabric descriptions see also: Hope 1979: 188; Hope et al. 2000: 194–5; Hope 2004b: 7–9. For the characteristics of the clay and ceramic materials of the Oases, see: Soukiassian, Wuttmann, Pantalacci 2002; Ballet, and Picon 1990: 75–85; Marchand and Tallet 1999: 307–52; Hope 1999: 215–43; Patten 2000: 87–104. See also: Nordström and Bourriau 1993: 168–82.

15. Gill 2016: 47–51.

16. Eccleston has further divided the ferruginous fabrics into four sub-categories, namely “Coarse Ferruginous Fabrics,” “Mudstone/Claystone/Shale Fabrics,” “Mudstone/Claystone/Shale Fabrics Vegetal Tempered Variant,” and “Mudstone/Claystone/Shale Fabrics - Sandstone Variant.” See Eccleston 2006: 93. See also Eccleston 2000: 211–18.

17. Originally, fabrics B1/B10/B15 were distinguished on the basis of their coarseness; Colin Hope has later grouped these fabrics together, as they are all made in the same basic paste. See Gill 2016: 50.

18. No source of the clay used for this fabric has been yet identified in the Dakhla Oasis. However, the presence of this fabric exclusively in the Dakhla Oasis and not in Kharga, where there are other types of calcium-rich clay, would seem to support the hypothesis of local production.

19. Vessels made in A11 are very common at Amheida in House B1 (Area 2.1), as well as in other buildings (Church B7, Area 2.3). Large amounts of this pottery were also found during the excavations of other sites in the Oasis such as Ismant el-Kharab/Kellis and ‘Ain el-Gedida, see: Hope 1979: 196; Hope 1981: 235; Hope 1985: 123, no. 2; Hope 1999: 235; Dixneuf 2012b: 459; Dixneuf 2018.

20. The A11 fabric is probably a later version of the fabric B23 (variants B16 and B17). This is a closed-grained, sand-rich fabric in a range of colors from yellow to white. It occurs in Dakhla with uncoated and red-coated surfaces from the late 3th/ early 4th century CE. The version of B23 fabric used during the Late Period is characterized by large limestone inclusions and fired gray throughout, and resembles a fabric from Bahariya oasis. Hope 1999: 235; Hope 2000: 194; Dunsmore 2002: 131; Hope 2004b: 9; Dixneuf 2012b: 459.

21. Hope 2004a: 103.

22. Eccleston 2006: 106. B3 or B3b is not related to other “B” fabrics. According to Hope, fabric B3 might have been used occasionally during the Late Period and during the Early Roman Period: Hope 1999: 232; Hope 2000: 195; Eccleston 2006: 104. Gill argues, however, that it also occurs regularly during the Ptolemaic Period: Gill 2016: 50.

23. About the workshops and the ceramics from Kysis (Kharga Oasis), here called Kharga Red Slip Ware, see Rodziewicz 1987; Ballet and Picon 1990: 298–301; Ballet and Vichy 1992: 116–9, Fig. 13 (g–h); Ballet 2001: 122–3. Phase III finale, see Ballet 2004: 224–5, 237 (Fig. 220, nos. 48–50).

24. Hayes 1972: 13–315.

25. Rodziewicz 1985: 235–41; Rodziewicz 1987: 123–36.

26. Hope 1979: 196; Hope 1980: 300–03, Pl. XXIV (e–k); Hope 1986: 87, figs. 8i–9ff; Ballet 2004: 224.

27. According to Ballet it is unlikely that the workshops that produced this type of fine ceramics were located in the Kharga Oasis; for this reason, she agrees with C. A. Hope’s suggestion that they were produced in the Dakhla Oasis. See Hope 1987; Ballet 2004: 211, n. 8.

28. In the Kharga Oasis the Red Slip Ware is produced in a red-brown clay (Munsell 4/8 10R, 10R 6/8), see Rodziewicz 1987: 124, n. 7.

29. The surfaces usually have decorative patterns incised or imprinted, see Rodziewicz 1987: 126–7.

30. Hope 1985: 123–4.

31. The fabrics of these amphorae have been described on the basis of the information collected in the websites http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk and http://www.cealex.org.

32. See Aston 1998: 30–1.

33. About the firing modes see Dixneuf 2018: 288–9.

34. The red ocher clay is made of iron minerals and of a clay component. In its natural state it is in the form of an earthy blob, relatively compact and powdered, red/brown in color: Cuomo di Caprio 2007: 285–6.

35. The iron minerals are mainly hematite and limonite, which are also present in ocher aggregates: a prevalence of hematite translates into a red color (red ocher), while a prevalence of limonite results into colors ranging from yellow to orange (yellow ocher). See Cuomo di Caprio 2007: 285–6.

36. The semi-liquid blend (also defined as semi-dense suspension) becomes a slip after firing and is applied by the potter on the surfaces of the container by means of dipping, perfusion, or brushing. See Cuomo di Caprio 2007: 290–3.

37. See Cuomo di Caprio 2007: 312.

38. The original bulk of the coding has been created and used by Hope for the study of the ostraca from Kellis: see Hope 2004: 7. Some colors and combinations have been added by the author according to the material analyzed in this study.

39. The Rhodian and Lake Mariout amphora fragments are not illustrated in the graph because they do not belong to the living phase of the house.

1. The presence of beige plaquette (schist), characteristic of the Oasis fabrics, does not seem to be always found in the Amheida productions, while according to P. Ballet the plaquettes are well attested in other sites not only in the Dakhla Oasis (Balat), but also in the Kharga Oasis (Douch/Kysis and el-Deir). See Ballet and Picon 1990: 75–84.

2. Eccleston 2006: 95–7.

3. Eccleston 2006: 95–7.

4. Eccleston 2006: 99–100. See also Gill 2016: 49, n. 4.

5. The firing method to obtain A5 was discussed directly in the field with P. Ballet (2014).

6. Gill 2016: 49, Pl. B.60. See also Eccleston 2006: 98–9.

7. The fabric description has been defined with P. Ballet during a workshop in January 2013 and February 2014 in Dakhla. See also for the description Gill 2016: 50.

8. Gill 2016: 50. See also Eccleston 2006: 112–14.

9. Gill 2016: 50. See also Eccleston 2006: 113.

10. Gill 2016: 50, Pls. B.63 and B.64. See also Eccleston 2006: 120.

11. The containers that are common to the Great Oasis, but for which no precise place of manufacturing has yet been found, are considered as regional. All the fabrics/wares that are not produced in the Great Oasis are grouped together as “imports” (i.e., Nile Valley amphorae and vessels; ceramics from other Egyptian areas; Mediterranean containers).

12. Peacock has distinguished six fabrics, of which Fabrics 1 and 2, both probably from the Rhodian Peraia, are by far the most common. Peacock 1977: 261–73. See also Tomber and Dore 1998: 112, 232.

40. For techniques in modeling clay, see Cuomo di Caprio 2007: 163–207.

41. See Dixneuf 2018: 287–8.

42. The thermae complex has been only partially excavated. See Davoli 2017: 193–220.

43. Phases have been defined by P. Davoli in Amheida VI, ch. 1. Phase III has been divided into 4 periods, difficult to date precisely. In this catalogue I use Phase III to refer to these periods.

44. A detailed description of the archaeological excavation and contexts of Area 2.1 (B1, S2, S3) is being prepared for publication by P. Davoli (Amheida VI).

45. The ostraca from Area 2.1 are published in O.Trim. 1 and O.Trim. 2, where the dating is discussed in detail.

46. These are being prepared for publication by David M. Ratzan.

47. These are being prepared for publication by Marina M. S. Nuovo (Amheida VII).

48. They are mainly amphorae, see Caputo 2014: 163–77; Caputo 2019: 168-91.

49. For a detailed description of these phases see Davoli, Amheida VI (forthcoming).