Читать книгу Silk Road Vegetarian - Dahlia Abraham-Klein - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMy Culinary Pilgrimage

Every Wednesday, I anxiously check my watch every few minutes until 2 p.m., the hour I pull my car out of the garage to make room for the load of fresh veggies for my Community Supported Agriculture group. At the stroke of two, Cornelius, the driver from Golden Earthworm, a farm on the east end of Long Island, New York, skillfully maneuvers his refrigerated truck just below the drive. He and Edvin, the farmer, are already exhausted from a long day’s work, but they haul box after box up the steep incline to my garage.

Slowly, the garage blossoms—until every nook and cranny holds a box near bursting with good, organically grown foods, the scent of earth still clinging to the just-picked produce. Soon, the CSA will open its doors and the members will come to collect their weekly boxes, buzzing with excitement to see what’s inside. For a few minutes, though, I’m alone with the bounty of summer, fragrant and ready to eat—ears of silken sweet corn, fragrant summer peaches, ripe red tomatoes, sleek green zucchini, dimpled raspberries the color of jewels.

I’ve traveled a long journey to arrive in the middle of this cornucopia. And though it might sound odd, it was a journey that began before I was born—several centuries before, actually, when my ancestors headed east from ancient Israel to Central Asia, joining countless other travelers on the storied trade route known as the Silk Road, where both commodities and cultures mingled. Sometimes, when I’m cozily ensconced in my home in Long Island, New York, surrounded by the riches of my CSA, I feel as though I am traveling with them, still on a Silk Road of sorts. My parents, Yehuda and Zina, instilled in me a love of learning about the many cultures of the world, and this love was often manifest at our table. Like so many people who love food and its historical aspects, I pick up recipes and ideas everywhere I go, from almost everyone I meet, and I fold them into my kitchen repertoire, just as my ancestors did.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. I grew up in New York, in a home where fresh, home-cooked food and enthusiastic entertaining, whether with our large extended family or international business associates, was the norm rather than the exception. Our dinner table regularly sat twenty guests from all over the world and was often elbow-to-elbow full. During the holidays, my parents adopted the literal meaning of the biblical words, “All who are hungry, let them come and eat.” It was a festive tableau of silverware clanking, wine goblets clinking to the words, “L’chaim—To life,” a table overflowing with luscious heirloom rice dishes and stuffed vegetables, aromatic stews and fresh fruits.

What distinguished my parents from those of my classmates was that they were part of the ancient Jewish community of Central Asia. In modern times, our family members were scattered all over the world, in Italy, Israel, Thailand, Hong Kong, Japan, and the U.S., but they could all trace their ancestry to the Babylonian Exile and Persian conquest, in the sixth century BCE. At that time, the great Temple in Jerusalem was destroyed and the Jews were forced into exile in Babylonia (now Iraq), which, in turn, was conquered by Persia (now Iran). For several centuries, my family traveled between Persia, Afghanistan and Bukhara (the capital of a province in Uzbekistan) as merchants; they spoke their own Jewish dialect of Farsi, Judeo-Persian, and cooked a kosher interpretation of the local food. In the early part of the nineteenth century, my family finally settled down in Afghanistan, smack in the middle of the Silk Road.

My paternal great grandfather near the Pyramids in 1914.

A family wedding party in Kabul in 1940.

My father at a 1960s Passover Seder meal wearing a traditional silk brocade called a jomah. He is holding a green onion as an illustration for one of the songs.

My grandfather buying sapphires in Burma in the 1960s.

My sister, being held by my father, at her first birthday party in Bombay.

THE SILK ROAD’S CULINARY HERITAGE

For those in the West familiar with it, most equate the Silk Road with China and its immediate neighbors, when in fact it was an extensive, interconnected network of trade routes across the Asian continent connecting East, South, and West Asia with the Mediterranean world, culminating in Italy. These Silk Routes (collectively known as the Silk Road) were important paths for cultural and commercial exchange between traders, merchants, pilgrims, missionaries, soldiers, and nomads from China, India, Tibet, the Persian Empire, and Mediterranean countries for almost 3,000 years.

The lucrative Chinese silk trade, which began during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) gave the “road” its name. Silk, however, was hardly the only commodity that moved along the route. All sorts of goods were traded—chief among them, spices, which were prized for their culinary, medicinal, and cosmetic value.

It’s the culinary heritage of the Silk Road that most fascinates me. If you could visualize the foods of the Silk Road, you’d see a collection of interconnecting sweeps and swirls revealing similarities and variations among cuisines and cultures. Reflecting the influence of the silk and spice trades, there are tastes of India and China in all the cuisines found along the Silk Road; above all, though, the Silk Road is a rich mosaic—each piece related but distinctly different. The same basic dish may be prepared in several different regions, but will vary depending on what grows in each place, how the local people expressed their nationalism, religion, and culture in their cooking, and how they were influenced by travelers. Many Central Asians, my family included, were a motley crew weaving through the trade routes and picking up their customs and dishes along their travels.

Most of the dishes of the region made use of local vegetables and the fundamental staple of the Silk Road: rice. The grain was first cultivated in China and India, and it was at least 5,000 years before it reached Persia in the fourth century BCE. Rice did not play an important role until the eighth century CE, but after that it became the centerpiece of the festive dishes called polows, known under different spellings in neighboring countries. The Bukharian green rice dish known as baksh is a variation on the Persian shevid polo, while the Bukharian oshi mosh (which looks just like it sounds) is a variation of the Indian kitchari, which is a staple comfort food in that country.

MY FAMILY’S CULINARY HERITAGE IN CENTRAL ASIA

My paternal great grandfather, known as Amin Kabuli, owned a vinyard in the region that is known today as Samarkand, Uzbekistan. The grapes were transformed into preserves and also wine, which was used locally for the Sabbath or sold for export. In fact, the Rothschild family heard about his renowned wine, and came to Samarkand requesting the seeds of his gigantic jeweled grapes so they could plant them in a vineyard in Israel. (When my paternal grandmother moved to the United States in the 1950s, she continued her family’s ancient tradition of growing grapes and making her own wine. My parents still have wine that she made over 40 years ago.)

In my grandfather’s day, Bukhara was a city in a southern province of Russia. As toddlers, my parents moved with their respective families to Kabul. There, my mother and her six siblings lived in a Jewish quarter, in an inner courtyard with closed gates, along with other families. The kitchen was a communal kitchen, of sorts. In the courtyard was a makeshift clay oven known as a tandoor that everyone used. The women in the courtyard would occasionally meet, serving tea along with a little gossip, a few jokes, and lots of laughter. To add to the congestion, many families kept a lamb and raised chickens in the courtyard to be ritually slaughtered for festive occasions. Large families and communal living demanded a practical solution to the challenge of meal preparation. Silk Road cooks found inspiration in one-pot meals consisting of all the essential ingredients for a balanced diet—not just in Afghanistan, but in Iran and Uzbekistan as well.

Most Westerners think of meat kabobs when they think of Persian and Afghan fare, but in truth, families rarely ate meat at home; it was saved for celebrations and holidays. Thus, Silk Road cooking had a strong vegetarian focus, partly due to the various religions flourishing there that encouraged a vegetarian diet, but chiefly because of economics. Vegetarian food was simply more affordable than meat.

As a result, preserving foods was essential in order to extend the season for all the fruits and vegetables that came to the table. Nearly every home had a big cellar for preserves, while root vegetables were kept covered with earth to preserve their freshness. Nothing went to waste—no composting was necessary, because all kitchen scraps were used as soup bases and fruit scraps were turned into preserves.

Despite the difficulties, a spirit of abundance shone throughout the cuisine. With rice, vegetables, fruit, nuts, and plenty of spices used in combination, there was always plenty to eat.

My mother (third from the left) scooping out a pilou in the 1960s.

Berry-Almond Coconut Scones (page 182) fresh from the oven.

MY FAMILY’S CULINARY HERITAGE IN INDIA

My mother lived in Kabul until she was a teenager, and then moved to Israel in 1949, a year after its founding. My father grew up in Kabul and worked as a tradesman before moving to Peshawar in what would become, when the British granted it independence, Pakistan. In 1947, the war between Pakistan and India prompted my father to move to Bombay, where he remained until he was thirty years old. During that time he visited Israel; he met my mother there, and they married in 1952. India was their home until 1956.

Bombay (now Mumbai) had been another stop for the traders and travelers of the Silk Road, and by the time my parents got there it was a melting pot of cultures, all drawn by the economic potential of this vibrant city. It was only natural that Bombay’s cuisine was as diverse as the country itself; however, there were certain characteristics that were unique to India. Because India was a predominantly Hindu country with a strong respect for life, many people followed the Hindu practice of strict vegetarianism. My newlywed mother quickly incorporated the Indian gastronomy, learning and cooking even more vegetarian dishes, which were prepared with cardamom, cinnamon, cumin, ginger, and mustard seed, to name just a few of the spices in her cabinet.

It was common for Jewish families like mine, with roots on the Silk Road, to trade as merchants. From their headquarters in Kabul, my family operated a diverse business that included the colorful world of gemstones, fabrics, and garments, as well as commodities such as car parts and tires. The business involved intercontinental transactions, so it was necessary to establish offices around the globe. My uncles opened satellite offices in Tokyo, Kobe, Hong Kong, Bombay, Bangkok, Milan, Valencia, Tel Aviv, and Chiasso and Lugano, in Switzerland. At the same time my parents headed for New York, and often traveled to the various world capitals.

MY OWN CULINARY TALE

Because of my father’s work and my family’s frequent travels, my parents absorbed the cultures, languages, tastes, and cuisines of all the places they lived in. They often entertained my father’s business associates, and my mother’s role as matriarch was to host and cook meals that made our guests feel at home. Our live-in helpers also came from diverse cultures and contributed their own favorites to our table. All these experiences influenced our cultural repertoire and expanded our culinary curiosity. The food I grew up with was an intermarriage of exotic tastes from Asian, African, European, Indian, and even some Latin dishes that formed a harmonious and tasty bliss. We were all always learning and sharing our cultures through cuisine.

What was unusual and wonderful about my mother’s cooking was that she was inspired by every culture she encountered and she instinctively knew how to integrate her native mix of Persian, Central Asian, and Indian food into any new cuisine she was learning about. Even before culinary adventurism became popular, she courageously tasted any and every ethnic cuisine she could try, and eventually incorporated them into her own delicious signature dishes.

And so I grew up, a typical New York kid in some ways, and in others a citizen of the world—at least at the table. As an adult, however, I did not follow my mother’s example at first. In traveling frequently and leading the lifestyle of a single New Yorker—with little time for home cooking or eating well—I gradually grew chronically ill, debilitated from a painful ulcer. While in New York, my typical diet was a doughnut in the morning, followed by pizza or a sandwich for lunch, and pasta for dinner. When I look back at those years, I’m astonished that I settled for eating so poorly. Back then, my goal was “eat to live,” and to do so as quickly as possible. Notice that I was not eating “live” foods, but processed quick-and-easy meals designed just to fill me up.

I went to see a conventional gastroenterologist who feebly attempted to correct my diet, suggesting bland foods like dairy and toast, and discouraging spicy foods. He then sent me off with a handful of medications. He did not ask me what my diet was like or what my heritage was; nor did he bother to investigate whether I had any food sensitivities. After months of following the regimen, I was not feeling any better and I decided to consult a holistic nutritionist. The nutritionist urged me to eliminate all wheat, dairy, and sugar from my diet. Ironically, wheat and dairy are precisely what the gastroenterologist had told me to eat! He also told me that I could eat spicy foods because I had grown up on them—that I should eat in harmony with my ancestral cuisine.

My first thought was, “What am I going to eat if I can’t eat wheat, dairy, and sugar?” And yet my body was taxed from years of over-consumption of processed foods. These three ingredients—wheat, dairy, and sugar—were wreaking havoc on my immune system. I plumbed my memories of my mother’s table and found answers in my ancestral cuisine.

Reacquainting myself with the diet of my childhood, which consisted largely of rice, vegetables, fruits, and beans, I discovered that the transformation wasn’t as difficult as I’d anticipated—especially because I felt so much better! My palate sobered up after many years of being “drugged.” I soon began detecting the artificial chemical flavors in processed foods that I’d never noticed before. Another added benefit was that, without the heavy carbohydrates and sugar fogging up my mind, my thinking became sharper. And I found that cooking engaged my spirit. Making healthy choices in the foods I ate was truly liberating.

Inspired to learn more about the link between food and wellness, I studied natural health and subsequently opened my own practice as a naturopath in 1994. In the ensuing years, I helped patients with chronic health issues—many related to food sensitivities. As a frequent guest on the Gary Null Radio Show, I addressed the concerns of listeners struggling with the same problems I once faced.

MY CULINARY CONVERSION

I’d been veering toward vegetarianism shortly after my second marriage to my South African husband. Mervin was already accustomed to healthy eating, purchasing food from the local food co-op and preparing homemade South African vegetarian meals. South Africa is a melting pot of cuisines, thanks to several waves of massive immigration, particularly Indian. Gastronomically speaking, we create an interesting Central Asian-African blend.

The turning point in our commitment to meat abstinence was shortly after we adopted Flynn, a sweet-natured cocker spaniel with an uncannily human face and a sweet, honest spirit. Abused by previous owners who cruelly dumped him onto the streets of Manhattan, Flynn was terribly skittish. He needed my full attention and pampering to recover from his ordeal.

On one particular Sabbath, my son, husband, and I, with Flynn by our side, sat at the table. Mervin recited the blessing over the wine and bread. That night I served garlic-rosemary roasted chicken. As I gazed at the headless chicken on my table, I looked over at Flynn’s gentle face, and I was struck by an epiphany. I realized that his presence in my life had altered my way of thinking. I questioned whether I could live with and love this needy animal while remaining a meat-eater. My conscience stung. Why was it okay to kill even one animal when we are all part of nature?

Thinking back, it’s no wonder that this thought struck me while we were sitting together over a sacred Sabbath meal, which is carefully chosen and prepared to remind us that we are not alone in the world, but are part of a collective wave of conscious thought on how we sow, how we harvest, how we slaughter, and how we eat. My relationship with Flynn taught me that vegetarianism is life-affirming; a vegetarian lifestyle expresses gratitude for our animal kingdom, rather than entitlement and ownership.

As my commitment to healthy and ethical eating grew, it was a natural progression to begin to purchase my foods from a local source. I decided to start a CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) program in my neighborhood. Golden Earthworm Farm became my partner, with some 40 like-minded households. The community connects through the rituals of harvesting, cooking, and sharing. We thrive on the joy of cooking whole foods and breaking bread together.

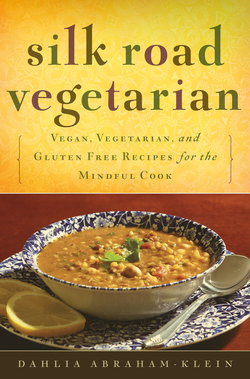

As time went on, I noticed that, as enthusiastic as they were, many of the CSA members had no idea what to do with some of the produce in their boxes. I was only too happy to share recipes, which culminated in my compiling a seasonal cookbook. Silk Road Vegetarian is an outgrowth of that first volume.

LOCAL AND SEASONAL EATING

It’s amazing to think that less than fifty years ago, almost all fruits and vegetables throughout the world were locally produced. That meant that people in tropical climates would have eaten tropical fruit in the fall, and people in northern climates would have eaten fruits like apples and pears. Today, most fruits in the supermarket are picked long before they are ripe, and sit in a truck or depot ripening for weeks before they get to us. But there’s a cost to this method, and it’s paid in quality. Foods that need to be shipped long distances are genetically bred to look presentable even when they’re old, rather than bred for taste or nutrition. The longer the produce sits before being eaten, the less its nutritional value to us.

When we purchase from a supermarket, we often don’t take into account the distance the produce must travel to reach our plates and the intervention that takes place to keep it in optimum condition. By buying from a farmers’ market or becoming a member of a CSA program—that is, buying a subscription for a season’s worth of produce from a local farm—you can be sure that your produce has been picked the same day that it’s ripe and delivered that very same day, as well. In this way, we are getting the optimal nutrition from the foods we eat, while minimizing energy consumption and waste involved in transporting foods for great distances.

Here I’m wearing a traditional silk Bukharian brocade reserved for special occasions.

My husband and I wearing silk jomahs.

The notion of buying locally grown produce might seem to be a bit of a conundrum in colder climates, where the growing season is short. However, winter root vegetables, some hothouse-grown foods, and preserved and frozen produce can be substituted for fresh.

As we understand and respond to the relationship between planet and plate, we can regain the balance in our lives and on our planet, reawaken our taste buds, and leave the world a better place for future generations.

AND SO, A BOOK

These recipes are inspired by my mother’s Silk Road cookery, and all the ingenious, loving Silk Road cooks who came before her. In my imagination, I’ve extended Silk Road cuisine all the way to Long Island, as I make use of local ingredients and combine them with seeds, pods, spices, and everything in-between to mimic the essence and flavor of the trade route. And in the same way that Central Asian food was adapted to varying tastes and lifestyles along the Silk Road, I have adapted my recipes to our modern American techniques and sensibilities.

My recipes also reflect my own preference for vegetarian fare that is free of wheat, gluten, and dairy. (Each recipe is labeled to identify its vegan, dairy-free, and gluten-free status.) I’ve tried to make the dishes appealing to all, whether strict or “occasional” vegetarians. For meat eaters who experience vegetarian meals as lacking fullness, Silk Road-style spices can add a whole new dimension to your food.

Unloading another fresh delivery from Golden Earthworm farm on the east end of Long Island, New York.

CSA member pick up.

I have heard some complain that a vegetarian diet is too time consuming and labor intensive for our modern world. It’s true that this food requires a good bit of peeling and chopping. Remember, though, that a good and healthy vegetarian diet isn’t supposed to be eaten in a car or on the run. Enjoying flavors and food, whether in the presence of those you care for or on your own, is good for your soul—your spirit will sit up and take notice.

Because I’m not a trained chef and have no formal culinary education, I have been very conscientious in creating a recipe book that is easy to follow. If I can cook these dishes, anyone can! Regardless of previous experience in the kitchen, these recipes are accessible to the home cook. While some require more practice and skill, most are suitable for the novice.

By both personal inclination and the tenets of my religion, I passionately believe we must all be good stewards of our planet. I’ve designed my recipes to foster seasonal eating. To this end, I’ve also included a section on food preservation through freezing (page 35) for readers whose local farms don’t have a year-round growing season. In this way, when you have an abundant supply of produce, you can preserve it when fresh and use it when it’s not in season.

Sharing my dishes with you is a sacred experience for me and I share them with love, from my heart and my hands, in the hope that when we cook together, we can create a groundswell of well-being for all. It is at the table that we connect with one another, our animals, our land, and our past. Cook, eat and enjoy!

www.silkroadvegetarian.com